Aghlabid architecture

Aghlabid architecture dates to the rule of the Aghlabid dynasty in Ifriqiya (modern-day Tunisia) during the 9th century and the beginning of the 10th century. The dynasty ruled nominally on behalf of the Abbasid Caliphs, with which they shared many political and cultural connections. Their architecture was heavily influenced by older antique (Roman and Byzantine) architecture in the region as well as by contemporary Abbasid architecture in the east.[1] The Aghlabid period is also distinguished by a relatively large number of monuments that have survived to the present day, a situation unusual for early Islamic architecture.[1] One of the most important monuments of this period, the Great Mosque of Kairouan, was a model for mosque architecture in the region. It features one of the oldest minarets and contains one of the oldest surviving mihrabs in Islamic architecture.[2][3]

Historical background[edit]

The Muslim conquest of North Africa took place progressively during the 7th century. During this period, the city of Kairouan was founded in 670 and served as the regional capital of the Maghreb.[4] The Great Mosque of Kairouan, the city's congregational mosque, was also initially founded in 670.[1] The Abbasid revolution in 750 put the Abbasid Caliphs in overall control of the Islamic empire, overthrowing the previous Umayyad Caliphs. In Ifriqiya, several rebellions and attacks on Kairouan, mainly from the Kharijites, had to be suppressed.[4]: 22

In 800 the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid appointed Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab as governor of the entire Maghreb (in theory, the lands west of Egypt).[5][4]: 23 He founded the Aghlabid dynasty, who ruled Ifriqiya nominally on behalf of the Abbasid Caliphs in Baghdad but were de facto autonomous.[6] In practice, their political power was mainly concentrated in the region of Ifriqiya.[4]: 23 Under their rule, Kairouan grew into the major cultural and spiritual center of Sunni Muslims in the Maghreb.[6] Although this city was in principle the political and economic capital, the Aghlabid rulers themselves usually resided in other nearby sites purpose-built for housing the government.[7]: 88–89 Sources claim that after coming to power in 800, Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab's first action was to found a new royal residence, al-Abbasiyya (named in honour of the Abbasids), just southeast of Kairouan.[7]: 95 It was built between 801 and 810,[8] and included its own congregational mosque and palaces.[9]

Under the rule of Ziyadat Allah I (r. 817–838), one of the most competent rulers of the dynasty, the Aghlabids embarked on a campaign of conquests in the central Mediterranean, including the conquest of Sicily (starting in 827), the conquest of Malta (870),[5] and expeditions to the Italian mainland (mostly in the 830s and 840s).[10]: 208 In 876 Ibrahim II ibn Ahmad moved the royal residence from al-Abbasiya to a new palace-city he founded, named Raqqada, again near Kairouan. The city contained a mosque, baths, market, and several palaces. He resided in a palace called Qaṣr al-Fatḥ (Arabic: قصر الفتح, lit. 'Palace of Victory'), which remained the residence of his successors (except for some periods where they moved to Tunis).[11]

Kairouan, as the center of Aghlabid power, received significant attention and patronage. The Aghlabid rulers concerned themselves with furnishing cities with water – seen as a pious duty – and with building or rebuilding mosques as physical expressions of the dynasty's presence and legitimacy.[7]: 96–98 The founding of new royal cities or residences, such as al-Abbasiya and Raqqada, also had symbolic value as part of the dynasty's portrayal of its own power, while probably also serving to distance it from social and political tensions within Kairouan.[7]: 95 Former Christians, converted to Islam, also played a central role in the field of architecture in Ifriqiya during this era. Some of them were freed slaves, known as mawali, who continued to serve their former masters, often serving as supervisors in the construction projects sponsored by their masters.[12]

Aghlabid rule began to weaken by the end of the 9th century and in 909 they were finally overthrown by a Kutama army led by Abu Abdallah al-Shi'i, establishing the new Fatimid Caliphate with Ifriqiya as its heartland.[5]

General characteristics[edit]

The century of Aghlabid rule saw a degree of political stability and continuity that allowed architectural patronage to flourish. The relatively large number of surviving monuments from this period in one region is unusual for this era of Islamic architecture, allowing for a more detailed study of their architectural development.[1]

Aghlabid architecture remained heavily influenced by the traditions of Antiquity, evidenced by the continuing extensive use of stone and some associated decorative techniques.[1] The ruins of Roman Africa were also frequently reused as a source of building materials, particularly for marble and cut stone.[12] The Aghlabids' connection to the Abbasids in Baghdad also meant that they imported or adopted the latest techniques from the metropolitan Abbasid style in Iraq, as seen in the luster-painted tiles of the mihrab in the Great Mosque of Kairouan, the carved stucco decoration in Raqqada, and the stone-carving of the Mosque of Ibn Khayrun.[1]

The use of the horseshoe arch in Ifriqya is evident in this period, though the form is not as pronounced as it was in other periods and regions of Moorish architecture. Some of the smaller arches, especially for mihrabs and in decorative compositions, have one continuous curve (i.e. one that could be drawn with a single pass of a compass), but most of the time the arches were slightly pointed or deformed near their upper summits.[13]: 45

During the Aghlabid period, the beginnings of geometrically-arranged arabesques can begin to be discerned, but this decorative technique was to be significantly enriched in later periods.[13]: 46 The geometric motifs typical of later Islamic art did not yet occupy a prominent role.[13]: 55 Arabic inscriptions carved in Kufic script were sparsely but widely used in decoration as well.[1] Various vegetal compositions of leaves and stems are attested in this period, with the designs differing depending on whether they were filling elongated friezes or larger panels.[13]: 46 One decorative motif specific to the Aghlabid period is the use of floral rosettes set inside squares, circles, or lozenges. These motifs were carved in stone and found in the mosques of Kairouan and Sousse. The square tiles on the mihrab of the Great Mosque of Kairouan are also arranged in a pattern that recalls this motif.[13]: 54

While many columns and capitals were reused from ancient buildings, some of the capitals of columns and colonettes found in Aghlabid mosques appear to be contemporary creations of the Aghlabid period. They have a simple and broadly-carved decoration of leaves on each side of the capital, ultimately inspired by ancient Corinthian models. They also resemble examples from Egypt, which Georges Marçais suggested may indicate a general style used in Islamic North Africa during this era.[13]: 46

Fortifications[edit]

Forts and ribats[edit]

The threat of Byzantine attacks by sea encouraged the construction of forts and fortifications along the coast of Ifriqiya.[1] Ribats were one type of structure which proliferated under Aghlabid rule.[13]: 29 They served as residential fortresses and religious retreats, simultaneously a defensive structure and a kind of Muslim monastery where pious warriors gathered for jihad. They were typically square or rectangular fortified enclosures with interior courtyards surrounded by chambers and communal rooms.[1][4]: 25 They were built at regular intervals along the coast.[1] Medieval geographers claimed that the ribats were built at precise distances from each other to allow signals to be passed from one to the other using mirrors and fires, thus allowing messages to travel rapidly along the North African coastline.[4]: 25 [14] The remains of many ribats and other small fortifications are still found along the Tunisian coastal areas.[1] Many of them were built over former Roman or Byzantine fortifications[15]: 139 or were former Byzantine forts restored by the Muslim garrisons.[13]: 29 The influence of Byzantine architecture continued to be evident in the fortifications built by the Aghlabids.[13]: 29–36

Of the many ribats built during this era, the Ribat of Sousse and the Ribat of Monastir are the most impressive surviving examples.[1] They are dated to the late 8th century (slightly prior to the Aghlabid period), making them the oldest surviving Islamic-era monuments in Tunisia – although they were both subjected to later modifications.[4]: 25 The Ribat of Monastir was founded in 796 by the Abbasid governor Harthama ibn A'yan, but it has gone through multiple modifications, restorations, and expansions, making the chronology of its construction difficult to outline. It gained prestige over time as a teaching place, as a religious retreat, and as a burial place.[4]: 26

The Ribat of Sousse, founded during the tenure of the Abbasid governor Yazid ibn Hatim al-Muhallabi (d. 787), is built of stone and consists of a square walled enclosure measuring around 38 meters long and 11 meters high.[4]: 25 Round towers reinforce its corners and the middle of its four sides, except for the southeastern corner, where a square tower serves as the base for a tall cylindrical tower on top of it. In the middle of the south side a projecting rectangular salient serves as the entrance gate. The gate is framed by reused ancient columns. Inside the gate are narrow openings for a former portcullis and for defenders to drop projectiles or boiling oil on attackers. Guardrooms were connected to the vestibule.[4]: 25 The gate leads to the courtyard, which is flanked by arcades on each side, behind which are lines of small rooms and an upper floor. On the south side of this upper floor is a vaulted room with a mihrab (niche symbolizing the direction of prayer) which is the oldest preserved mosque or prayer hall in North Africa. Another small room in the fortress, located above the gate, contains another mihrab and is covered by a dome supported on squinches. This is the oldest example of a dome with squinches in Islamic North Africa.[4]: 25 The cylindrical tower above the southeast corner was most likely intended as a lighthouse. It can be ascended via a spiral staircase inside. It has a marble plaque over its entrance inscribed with the name of Ziyadat Allah I and the date 821, which is the oldest Islamic-era monumental inscription to survive in Tunisia.[4]: 25–26 This date has been interpreted by some scholars as the foundation date of the whole ribat rather than the construction date of the tower only,[4]: 26 or as the date of a reconstruction.[16][15]: 139

City walls[edit]

The city walls of Sfax are recorded to have been built in 859 by the local qadi, ‘Ali Ibn Aslam al-Bakri, under the reign of Abu Ibrahim Ahmad (r. 856–863).[17][13]: 36 The walls have been significantly restored and modified over time.[13]: 36 They have a roughly quadrilateral or rectangular outline and are fortified today with some 69 towers of varying shapes – generally rectangular but some polygonal.[17][13]: 36 The city's Kasbah (citadel) and three other more heavily fortified towers or bastions occupy the four corners of this rectangle.[17] The Aghlabid fortifications consisted of curtain walls built of rubble stone and cut stone, with a wall walk running along the top. Their outer façade is usually inclined and sometimes widened at the base. Some towers are embellished on the outside by a cornice with dentils.[13]: 36

The old city of Sousse has also preserved some of its defensive walls, which a surviving inscription dates to 859.[4]: 27 The walls are built of stone, which is common for buildings in this city, but city walls elsewhere in the Maghreb were usually built in rammed earth or brick.[4]: 27–28 The walls are topped by rounded crenellations following the Byzantine tradition.[18] At the southwestern corner of the walls is the Kasbah, which was first built in 850 under the reign of Abu al-Abbas Muhammad (r. 841–856) but rebuilt many times since then.[18] At the Kasbah's southwest corner is a much taller tower known as the tower of Khalaf al-Fata, named after a freed slave and state official who served Ziyadat Allah I and who supervised the construction.[4]: 27 [18] It was constructed around the time of the Kasbah's foundation.[18] This tower also probably served as a lighthouse or signal tower.[1][18] It is 13 meters tall,[18] but as it is built on an elevated site its summit stands 77 meters above sea level, making it visible from afar and giving it commanding views over the area.[4]: 27 The tower consists of two cuboid sections stacked on top of each other, whose interiors are occupied by four rooms. The room on the second floor has a small mihrab, indicating that it served as a prayer room for the soldiers garrisoning it.[4]: 27

Mosques[edit]

Great Mosque of Kairouan[edit]

One of the most important Aghlabid monuments is the Great Mosque of Kairouan, which was completely rebuilt in 836 by the emir Ziyadat Allah I, although various additions and repairs were effected later which complicate the chronology of its construction.[4]: 28–32 Aside from Ziyadat Allah I's construction, it seems another campaign of repairs and renovations took place under Abu Ibrahim Ahmad.[9][4]: 28, 32 The mosque's design was a major reference point in the architectural history of mosques in the Maghreb.[19]: 273 The mosque features an enormous rectangular courtyard, a large hypostyle prayer hall, and a thick three-story minaret. The prayer hall is divided into 17 aisles or naves by rows of arches, with a transverse aisle on the south side running along the qibla wall, perpendicular to the others. The columns are fashioned from different kinds of marble, granite, and porphyry, while their capitals have varying designs, indicating that they were spoliated from many different older structures.[4]: 29 The prayer hall's layout also reflects an early use of the so-called "T-plan", as the central nave (the one leading to the mihrab) and the transverse aisle along the qibla wall are wider than the other aisles and they both intersect in front of the mihrab.[20] The entrance to the central nave from the courtyard is fronted by a high dome called the Qubbat al-Bahw (or Qubbat al-Bahu; meaning "Dome of the Vestibule" or "Dome of the Covered Gallery").[4]: 29

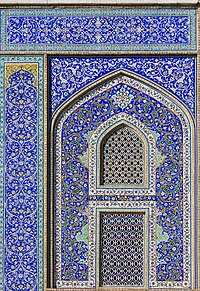

The mihrab is among the oldest examples of its kind, richly decorated with marble panels carved in high-relief vegetal motifs and with ceramic tiles with overglaze and luster.[4]: 30 [3] Next to the mihrab is the oldest surviving minbar (pulpit) in the world, made of richly-carved teakwood panels. Both the carved panels of the minbar and the ceramic tiles of the mihrab are believed to be imports from Abbasid Iraq.[4]: 30–32 An elegant dome in front of the mihrab with an elaborately-decorated drum is one of architectural highlights of this period. Its light construction contrasts with the bulky structure of the surrounding mosque and the dome's drum is elaborately decorated with a frieze of blind arches, squinches carved in the shape of shells, and various motifs carved in low-relief.[4]: 30–32 The dome, along with the galleries around the courtyard, the minbar, and the tiles of the mihrab are dated to Abu Ibrahim Ahmad's intervention in the mosque.[9][4]: 32

It was under Abbasid rule in that the first known tower minarets appeared.[21] According to art historian Jonathan Bloom, the early Abbasid minarets were not built to host the call to prayer but were instead intended as prominent landmarks symbolizing the presence of Islam, suitable for major congregational mosques. Their function as a platform for the muezzin and the call to prayer only developed later.[21]: 64, 107–108 As the first minaret towers were an innovation introduced by the Abbasids, they were symbolically associated with Abbasid power.[22][23] The minaret of the Great Mosque of Kairouan, which came from the Aghlabid reconstruction, is the oldest surviving one in North Africa and the western Islamic world, and one of the oldest in the world.[2][24] It consists of a massive square-based tower, 10.5 meters wide at the base and tapering towards the top of its 18.5 meters-tall shaft. This main section is surmounted by a second square tier, which in turn is topped by a third domed section (the latter being reconstructed at a later period).[4]: 32 The tower's form was likely modeled on older Roman lighthouses in North Africa, quite possibly the lighthouse at Salakta (Sullecthum) in particular.[4]: 32 [25][26]: 138

- Great Mosque of Kairouan

-

Courtyard of the mosque, looking north to the minaret

-

Courtyard façade of the prayer hall, with the Qubbat al-Bahw dome in the middle

-

Prayer hall, central nave leading to the mihrab

-

Prayer hall, transversal view of the rows of arches and columns

-

View of the mihrab area

-

Detail of the mihrab, showing the square luster tiles around the upper section

-

Detail of the carved marble panels inside the mihrab

-

The dome in front of the mihrab

-

The minaret

Other congregational mosques[edit]

The congregational mosque of the Aghlabid administrative capital, al-Abbasiya, is described by al-Baladhuri (d. 892) as measuring 200 by 200 cubits and constructed of brick and marble columns, with a cedarwood roof. The description resembles that of the congregational mosque in Baghdad at the time, which may mean that either the Aghlabid mosque was inspired by it or that the description itself is merely a formulaic one.[4]: 23–25 The Great Mosque of al-Zaytuna in Tunis, which was founded earlier around 698, owes its overall current form to a reconstruction during the reign of the Aghlabid emir Abu Ibrahim Ahmad (r. 856–863). Its layout is very similar to the Great Mosque of Kairouan, with a courtyard and hypostyle prayer hall, but it lacked a minaret. Most of the mosque's details and decoration were modified in later periods, and its present minaret is likewise a later addition.[27][4]: 38–41 [28] The sections that are best preserved from the 9th century are the interior of the prayer hall (though some of this was later rebuilt too) and the projecting round corner bastions at the northern and eastern corners of the mosque.[4]: 38–40 Two other congregational mosques in Tunisia, the Great Mosque of Sfax (circa 849) and the Great Mosque of Sousse (851), were also built by the Aghlabids but have quite different forms.[4]: 36–37

The Great Mosque of Sousse was commissioned in 851 by Abu'l-Abbas Muhammad I and its construction was supervised by Mudam al-Khadim, a freed slave and mawla of Abu'l-Abbas.[29][13]: 23 It has a rectangular floor plan measuring about 57 metres wide and 50 metres long[4]: 36 (or 59 by 51 metres according to another source[30]), divided between a courtyard and a prayer hall. The prayer hall has 13 naves separated by rows of arches.[30] The hall was originally three bays (three arches) deep, but it was subsequently extended later the same century by demolishing the qibla wall and extending it for the length of another three bays.[4]: 36 [30] Its current mihrab dates from the later Zirid period.[30] While the floor plan is not very different from that of the Great Mosque of Kairouan, the structure of the building is very different.[13]: 24 [30] Rather than being covered by flat wooden ceilings, the prayer hall is covered with rubble stone vaults.[30] The hall's original bays are covered with barrel vaults while the bays of the later extension are covered by groin vaults.[4]: 36 [13]: 72 The dome in front of the original mihrab is still present, now in the middle of the prayer hall, and resembles the domes of the Great Mosque of Kairouan: it has an octagonal drum, scalloped squinches, a Kufic inscription, and carved floral decoration.[30] The two tympanums of the arches on either side, below the dome, are covered in a carved checkerboard-like motif of lozenges filled with floral and rosette motifs.[13]: 54 [4]: 37 In the mosque courtyard, a long Kufic inscription runs in a cornice along the top edge of the walls around the courtyard, containing most Qur'anic excerpts. On the south side of the courtyard the inscription is now hidden behind an extra arcaded portico that was added in the 11th century (and restored in 1675) in front of the prayer hall's original arcaded façade.[4]: 36–37 [30] At the mosque's northeast corner is a cylindrical bastion topped by a domed octagonal pavilion, which was likely a sawma'a, a space at roof level where the muezzin could issue the call to prayer.[4]: 37

The Great Mosque of Sfax is not precisely date but assumed to be built around the same time, circa 849, but it was extensively modified after the Aghlabid period.[4]: 37 [1] The sponsor of its construction was reputedly the qadi 'Ali ibn Aslam al-Jabanyani.[4]: 37 The mosque has a small rectangular courtyard and a large hypostyle prayer hall, but it seems that in the 10th century, perhaps in 988[a], the mosque was reduced in size by suppressing its western half, giving it a narrower floor plan.[13]: 72 [15]: 135 [4]: 37 The original mihrab was replaced with a new one of Zirid style at the middle of the shortened qibla wall.[31] The minaret, which might have originally been located at the middle of the courtyard's north side (like at the Great Mosque of Kairouan), would have thus found itself at the corner of a reduced courtyard.[13]: 73 [4]: 37 The original Aghlabid minaret, probably a fairly slender two-story tower, is now hidden inside a larger Zirid minaret built around it in the early 11th century.[4]: 37 The mosque was then enlarged again in the 18th century by re-extending the prayer hall to the west, giving it its present layout.[31] The original Aghlabid form of the mosque may have thus been very similar to the Great Mosque of Kairouan. Like at the latter, the prayer hall was covered by a flat wooden ceiling supported by arches resting on reused ancient columns.[13]: 25 The eastern exterior façade of the mosque is embellished with a series of decorative horseshoe arch-shaped niches. These may be from the original mosque but their unusual appearance may date them to a later period,[4]: 38 most likely the Zirid period.[31][13]: 108

Small mosques[edit]

While the Aghlabid rulers sponsored the construction of large congregational mosques to publicly express their piety and enhance their reputation, local patrons with less wealth at their disposal still commissioned the construction of small neighbourhood mosques.[4]: 33 The small Mosque of Ibn Khayrun in Kairouan, also known as the "Mosque of the Three Doors", is one such example. The inscription on its façade attributes its foundation to a little known patron, Muhammad Ibn Khayrun, in 866.[32] According to scholar Mourad Rammah, the mosque's façade is the oldest decorated external façade in Islamic architecture.[32] Made of limestone, it is carved with Kufic inscriptions as well as with vegetal motifs such as tendrils and rosettes.[4]: 33–34 [15]: 136

Another small local mosque from this period is the Mosque of Bu Fatata in Sousse, dated to the reign of Abu Iqal al-Aghlab ibn Ibrahim (r. 838–841). Also built in limestone, it has a hypostyle prayer hall fronted by an external portico of three arches. A large Kufic inscription is carved across the top of the front façade.[4]: 33–34 Both the Ibn Khayrun and Bu Fatata mosques are early examples of the "nine-bay" mosque, meaning that the interior has a square plan subdivided into nine smaller square spaces, usually vaulted, arranged in three rows of three. This type of layout is subsequently found in many parts of the Islamic world, in al-Andalus and as far as Central Asia, suggesting that the design may have been disseminated widely by Muslim pilgrims returning from Mecca.[4]: 33–34 Both mosques were given minarets during the Hafsid period.[4]: 33 [32]

Palaces[edit]

Al-Abbasiyya[edit]

Little remains or is known about the Aghlabid royal residence at al-Abbasiyya.[33][34]: 3 Ibrahim I ibn al-Aghlab's palace was known as ar-Rusafa, a toponym which may have been associated with a particular kind of garden estate. This same name was given to country estates in earlier in Umayyad Syria and in later in Umayyad al-Andalus.[34]: 3 Al-Abbasiya also had a congregational mosque, a market, and another palace named Qaṣr al-Abyad ("White Palace"), making it essentially its own city.[9][34]: 3

Raqqada[edit]

Of the later royal city and residence of Raqqada, some remains have been partially excavated.[4]: 25 It was located 4 kilometers south of Kairouan and remains have been found across a site of approximately 9 square kilometers, suggesting that the city grew fairly large.[34]: 3 Fragments of carved stucco decoration similar to that of Abbasid Samarra have been found at the site.[1]

Only one palace building has been investigated by archeologists. It was built of mudbrick and went through multiple phases of construction and expansion. It was first constructed as a roughly square walled enclosure, measuring 55 by 55 meters, whose exterior was reinforced with round towers or buttresses. Buttressed walls like this were a feature of Roman castrum architecture and were also found in early Islamic architecture.[34] The building had a central rectangular courtyard surrounded by rooms, including a large reception room in the middle of the north side. Judging by its layout, this building may correspond to what historical sources refer to as the Qaṣr aṣ-Ṣaḥn ("Courtyard Palace").[34] The building was entered from the south via a bent entrance (a passage turning 90 degrees twice), a feature which became common in the Abbasid period as both a defensive measure and as a means to preserve the privacy of the inhabitants inside. The entrance led directly into the courtyard. A cistern existed under the center of the courtyard where rainwater was collected and stored for future use. The reception room to the north, roughly square in shape, was divided into three north-to-south naves by two rows of four columns. A small apse or semi-circular niche at the back of the hall probably marked the location of the emir's seat or throne.[34] This type of basilical columned hall became a recurring feature of palatial architecture in the western Islamic world.[35] In a later building phase, this palace enclosure was expanded to the north and west until it measured 105 by 105 meters. The additional space was filled with living quarters.[34] The interior underwent further reorganization later during the Fatimid and Zirid occupations of the site.[35]: 48–49

This courtyard palace was surrounded by a residential district and many other structures. To its northeast was a large irregular quadrilateral water basin measuring between 90 and 130 meters wide. It likely functioned as a reservoir for the royal city's water supply, but it may have also been integrated into the architectural landscape of the palaces.[35]: 9 Of the other palaces mentioned in historical sources, one was the Qaṣr aṣ-Baḥr ("Water Palace" or "Palace of the Sea"), which would indicate a palace associated with a large water basin.[35]: 9–11 This palace has not yet been found at Raqqada, but there is evidence of structures existing next to the aforementioned quadrilateral water basin, which could be identified as a part of this palace.[15]: 137 [35]: 10 Large bodies of water would have played an aesthetic role by reflecting the images of adjoining buildings and giving them a lighter appearance.[35]: 11 The water basin at Raqqada may have also been used for boat parties and water jousting events.[15]: 137 The Qaṣr aṣ-Baḥr at Raqqada is the earliest example of such a "water palace" in the Mediterranean region, with later examples found at the Fatimid capital al-Mansuriyya and the Hammadid capital Qal'at Bani Hammad. It may have been inspired by the palaces of Abbasid Samarra, where a large pool existed in front of the Bab al-'Amma gate, and it probably had its origins in older Sassanian palace architecture, such as Qaṣr e-Shirin in Iran.[35]: 9–11, 129 A third named palace, the Qaṣr al-Fatḥ ("Palace of Victory"), was the residence of emir Ibrahim II,[11] but its location is unknown.[35]: 9

Civic works[edit]

The Aghlabids also extensively built up infrastructure and other buildings with civic purposes. Historical texts indicate that numerous built hammams (public baths), caravanserais, and maristans (hospitals or asylums), though these have not survived. They built many bridges over rivers, two of which survive near Kairouan and Hergla.[1]

Water infrastructure[edit]

Hydraulic engineering already had a long tradition in the region and many aqueducts and other waterworks from the Roman and Byzantine period survived or were restored in the early Islamic period.[15]: 137 The Sofra, a cistern in the center of old Sousse, may have been a pre-Islamic cistern which was restored or rebuilt by Ibrahim II (r. 875–902). It consists of a large barrel-vaulted chamber divided by rows of arches supported by square pillars, with rectangular openings in the roof that allowed water to be added from the outside. A small round settling tank also stands on its south side.[15]: 137–138

The Aghlabids also constructed extensive new waterworks to provide water to Kairouan and their nearby palatial complexes, which are located in a dry and arid region.[1] Water was collected in a series of large reservoirs, two of which survive today outside the walls of Kairouan, known as the Aghlabid Basins. During the Aghlabid period, water was brought to the city and the reservoirs from the surrounding lowlands by drawing it from Oued Merguellil and its tributaries.[36][37][38] The waters were diverted by a system of small dams, weirs, and canals to the reservoirs.[36][37] An aqueduct was also built to bring water from springs in the Shreshira (or Chrechira) Mountains, 36 kilometres west of Kairouan.[39][40][41][42] The aqueduct was probably built during the Aghlabid period, but made use of some existing Roman-era infrastructure and was subsequently renovated during the Fatimid period.[39][40][42] The two surviving Aghlabid reservoirs of Kairouan, built between 860 and 862, are each composed of two large circular basins that acted as settling tanks, which in turn led filled a covered cistern.[43] In the middle of the largest water basin is a polylobed masonry pillar today which may have been part of the foundations of a leisure pavilion that stood above the water.[44][45] Nearby Raqqada was also supplied by large above-ground square reservoirs whose walls were reinforced with round towers.[1]

Maristans (hospitals)[edit]

The first known maristan built in present-day Tunisia was built by Ziyadat Allah I between 825 and 835 in the Dimma neighbourhood of Kairouan.[46] This maristan became the model for other maristans built later in Tunis, Sfax, and Sousse. The first maristan of Tunis was founded circa 903, located outside the city walls.[46] The usual layout for these buildings had a central courtyard surrounded by an arcaded gallery leading to many rooms. The entrance was through a covered passage (a skifa) on the central axis of the courtyard. Along this passage were benches for visitors coming to see patients, as well as rooms for the guards. Across the courtyard from the entrance was usually a prayer room. From the courtyard one could also access an isolated section reserved for patients with leprosy. Maristans were often equipped with their own cistern and well to provide water.[46]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Architecture; IV. c. 750–c. 900; C. Tunisia". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Minaret". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 530–533. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Mihrab". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. pp. 515–517. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700–1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300218701.

- ^ a b c Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2004). "The Aghlabids". The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748696482.

- ^ a b Bosworth, C.E. (2013). "Aghlabids (AD 800–909)". In Netton, Ian Richard (ed.). Encyclopedia of Islamic Civilization and Religion. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-17967-0.

- ^ a b c d Goodson, Caroline (2018). "Topographies of Power in Aghlabid-Era Kairouan". In Anderson, Glaire D.; Fenwick, Corisande; Rosser-Owen, Mariam (eds.). The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors: Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa. Brill. pp. 88–105. ISBN 978-90-04-35566-8.

- ^ Lev, Yaacov (1991). State and Society in Fatimid Egypt (Volume 1 dari Arab history and civilization. Studies and texts: 0925–2908 ed.). Brill. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9004093443.

- ^ a b c d Bloom, Jonathan M.; Blair, Sheila S., eds. (2009). "Aghlabid". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ Nef, Annliese (2021). "Byzantium and Islam in Southern Italy (7th-11th Century)". A Companion to Byzantine Italy. Brill. pp. 200–225. ISBN 978-90-04-30770-4.

- ^ a b Marçais, Georges (1995). "Raḳḳāda". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 414–415. ISBN 978-90-04-09834-3.

- ^ a b Binous, Jamila; Baklouti, Naceur; Ben Tanfous, Aziza; Bouteraa, Kadri; Rammah, Mourad; Zouari, Ali (2010). Ifriqiya: Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia. Islamic Art in the Mediterranean (2nd ed.). Museum With No Frontiers & Ministry of Culture, the National Institute of Heritage, Tunis. ISBN 9783902782199.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques.

- ^ Anderson, Glaire D.; Fenwick, Corisande; Rosser-Owen, Mariam (2018). "The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors: An Introduction". In Anderson, Glaire D.; Fenwick, Corisande; Rosser-Owen, Mariam (eds.). The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors: Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa. Brill. pp. 4, 75. ISBN 978-90-04-35566-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mazot, Sibylle (2011). "The Architecture of the Aghlabids". In Hattstein, Markus; Delius, Peter (eds.). Islam: Art and Architecture. h.f.ullmann. pp. 132–139. ISBN 9783848003808.

- ^ Binous, Jamila; Baklouti, Naceur; Ben Tanfous, Aziza; Bouteraa, Kadri; Rammah, Mourad; Zouari, Ali (2010). "VII. 3. a The Ribat". Ifriqiya: Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia. Islamic Art in the Mediterranean (2nd ed.). Museum With No Frontiers & Ministry of Culture, the National Institute of Heritage, Tunis. ISBN 9783902782199.

- ^ a b c Binous, Jamila; Baklouti, Naceur; Ben Tanfous, Aziza; Bouteraa, Kadri; Rammah, Mourad; Zouari, Ali (2010). "VIII. 1. k The Ramparts". Ifriqiya: Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia. Islamic Art in the Mediterranean (2nd ed.). Museum With No Frontiers & Ministry of Culture, the National Institute of Heritage, Tunis. ISBN 9783902782199.

- ^ a b c d e f Binous, Jamila; Baklouti, Naceur; Ben Tanfous, Aziza; Bouteraa, Kadri; Rammah, Mourad; Zouari, Ali (2010). "VII. 3. g The Kasbah and the Ramparts". Ifriqiya: Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia. Islamic Art in the Mediterranean (2nd ed.). Museum With No Frontiers & Ministry of Culture, the National Institute of Heritage, Tunis. ISBN 9783902782199.

- ^ a b Lamine, Sihem (2018). "The Zaytuna: The Mosque of a Rebellious City". In Anderson, Glaire D.; Fenwick, Corisande; Rosser-Owen, Mariam (eds.). The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors: Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa. Brill. pp. 269–293. ISBN 978-90-04-35566-8.

- ^ M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Architecture". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 68–212. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b Bloom, Jonathan M. (2013). The minaret. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748637256. OCLC 856037134.

- ^ Petersen, Andrew (1996). Dictionary of Islamic architecture. Routledge. pp. 187–188. ISBN 9781134613663.

Although the mosques of Damascus, Fustat and Medina had towers during the Umayyad period it is now generally agreed that the minaret was introduced during the Abbasid period (i.e. after 750 CE). Six mosques dated to the early ninth century all have a single tower or minaret attached to the wall opposite the mihrab. The purpose of the minaret in these mosques was to demonstrate the power of Abbasid religious authority. Those opposed to Abbasid power would not adopt this symbol of conformity, thus Fatimid mosques did not have towers.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M. (2013). The minaret. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748637256. OCLC 856037134.

- ^ Petersen, Andrew (1996). Dictionary of Islamic architecture. Routledge. pp. 187–190. ISBN 9781134613663.

- ^ Hillenbrand, Robert; Burton-Page, J.; Freeman-Greenville, G.S.P. (1991). "Manār, Manāra". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Vol. 6. Brill. pp. 358–370. ISBN 9789004161214.

- ^ Guidetti, Mattia (2017). "Sacred Spaces in Early Islam". In Flood, Finbarr Barry; Necipoğlu, Gülru (eds.). A Companion to Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 1. Wiley Blackwell. pp. 130–150. ISBN 9781119068662.

- ^ Binous, Jamila; Baklouti, Naceur; Ben Tanfous, Aziza; Bouteraa, Kadri; Rammah, Mourad; Zouari, Ali (2002). "I. 1. l The Great Mosque of Zituna". Ifriqiya: Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia (2nd ed.). Museum With No Frontiers, MWNF. ISBN 9783902782199.

- ^ Chater, Khalifa (2002). "Zaytūna". In Bearman, P.; Bianquis, Th.; Bosworth, C.E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W.P. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Vol. XI. Brill. pp. 488–490. ISBN 9789004161214.

- ^ Johns, Jeremy (2018). "The Palermo Quran (AH 372/982–3 CE) and its Historical Context". In Anderson, Glaire D.; Fenwick, Corisande; Rosser-Owen, Mariam (eds.). The Aghlabids and Their Neighbors: Art and Material Culture in Ninth-Century North Africa. Brill. p. 601. ISBN 978-90-04-35566-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Binous, Jamila; Baklouti, Naceur; Ben Tanfous, Aziza; Bouteraa, Kadri; Rammah, Mourad; Zouari, Ali (2010). "VII. 3. b The Great Mosque". Ifriqiya: Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia. Islamic Art in the Mediterranean (2nd ed.). Museum With No Frontiers & Ministry of Culture, the National Institute of Heritage, Tunis. ISBN 9783902782199.

- ^ a b c d Binous, Jamila; Baklouti, Naceur; Ben Tanfous, Aziza; Bouteraa, Kadri; Rammah, Mourad; Zouari, Ali (2010). "VIII. 1. f The Great Mosque". Ifriqiya: Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia. Islamic Art in the Mediterranean (2nd ed.). Museum With No Frontiers & Ministry of Culture, the National Institute of Heritage, Tunis. ISBN 9783902782199.

- ^ a b c Binous, Jamila; Baklouti, Naceur; Ben Tanfous, Aziza; Bouteraa, Kadri; Rammah, Mourad; Zouari, Ali (2010). "V. 1. e Ibn Khayrun Mosque, or Mosque of the Three Gates". Ifriqiya: Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia. Islamic Art in the Mediterranean (2nd ed.). Museum With No Frontiers & Ministry of Culture, the National Institute of Heritage, Tunis. ISBN 9783902782199.

- ^ M. Bloom, Jonathan; S. Blair, Sheila, eds. (2009). "Kairouan". The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Arnold, Felix (2017). Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean: A History. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–11. ISBN 9780190624552.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Arnold, Felix (2017). Islamic Palace Architecture in the Western Mediterranean: A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190624552.

- ^ a b Binous, Jamila; Baklouti, Naceur; Ben Tanfous, Aziza; Bouteraa, Kadri; Rammah, Mourad; Zouari, Ali (2002). "V.1.g. The Aghlabid Reservoirs". Ifriqiya: Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia (2nd ed.). Museum With No Frontiers, MWNF. ISBN 9783902782199.

- ^ a b "Qantara - The Aghlabid Pools". Qantara, Mediterranean Heritage. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800. Yale University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9780300218701.

- ^ a b Marçais, Georges (1954). L'architecture musulmane d'Occident. Paris: Arts et métiers graphiques. pp. 37–38.

- ^ a b Glick, Thomas F. (2007). "Aqueduct". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three. Brill. ISBN 9789004161658.

- ^ Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2011). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 166. ISBN 9780812207286.

- ^ a b Binous, Jamila; Baklouti, Naceur; Ben Tanfous, Aziza; Bouteraa, Kadri; Rammah, Mourad; Zouari, Ali (2010). "IV.2.a. Fatimid Bridge-Aqueduct of Chrechira". Ifriqiya: Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia. Islamic Art in the Mediterranean. Museum With No Frontiers & Ministry of Culture, the National Institute of Heritage, Tunis.

- ^ Binous, Jamila; Baklouti, Naceur; Ben Tanfous, Aziza; Bouteraa, Kadri; Rammah, Mourad; Zouari, Ali (2002). "V.1.g. The Aghlabid Reservoirs". Ifriqiya: Thirteen Centuries of Art and Architecture in Tunisia (2nd ed.). Museum With No Frontiers, MWNF. ISBN 9783902782199.

- ^ Ruggles, D. Fairchild (2011). Islamic Gardens and Landscapes. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 166. ISBN 9780812207286.

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800. Yale University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 9780300218701.

- ^ a b c Hakim, Besim Selim (2013). Arabic Islamic Cities: Building and Planning Principles. Routledge. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-136-14074-7.