Assassination of Alexander II of Russia

Painting of Alexander II on his deathbed by Konstantin Makovsky | |

| Date | 13 March 1881 |

|---|---|

| Location | Near the Catherine Canal, Saint Petersburg |

| Coordinates | 59°56′24″N 30°19′43″E / 59.94000°N 30.32861°E |

| Deaths | Alexander II of Russia, Ignacy Hryniewiecki, Alexander Maleichev, Nikolai M. Zakharov, and possibly others. |

| Convicted | Members of Narodnaya Volya |

| Charges | Regicide |

| Weapon | Nitroglycerin and piroxylin bombs |

On 13 March [O.S. 1 March] 1881, Alexander II, the Emperor of Russia, was assassinated in Saint Petersburg, Russia while returning to the Winter Palace from Mikhailovsky Manège in a closed carriage.

The assassination was planned by the Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya ("People's Will"), chiefly by Andrei Zhelyabov. Of the four assassins coordinated by Sophia Perovskaya, two of them actually committed the deed. One assassin, Nikolai Rysakov, threw a bomb which damaged the carriage, prompting the Tsar to disembark. At this point a second assassin, Ignacy Hryniewiecki, threw a bomb that fatally wounded Alexander II.

Alexander II had previously survived several attempts on his life, including the attempts by Dmitry Karakozov and Alexander Soloviev, the attempt to dynamite the imperial train in Zaporizhzhia, and the bombing of the Winter Palace in February 1880. The assassination is popularly considered to be the most successful action by the Russian nihilist movement of the 19th century.

Conspirators[edit]

On 25–26 August 1879, on the anniversary of his coronation, the 22-member Executive Committee of Narodnaya Volya resolved to assassinate Alexander II in the hopes that it would precipitate a revolution.[1][2] Over the subsequent year and a half, the various attempts on Alexander's life had ended in failure. The Committee then decided to assassinate Alexander II on his way back to the Winter Palace following his usual Sunday visit to the Mikhailovsky Manège. Andrei Zhelyabov was the chief organizer of the plot. The group had observed his routines for a couple of months and was able to deduce the alternate intentions of the entourage. They found that the Tsar would head for home either by going through Malaya Sadovaya Street or by driving along the Catherine Canal. If by the Malaya Sadovaya, the plan was to detonate a mine placed under the street. To further ensure the success of the plot, four bomb-throwers were to loiter at the corners of the street; after the explosion, all of them were to close in on the Tsar and use their bombs if necessary. If, in contrast, the Tsar passed by the canal, the bomb-throwers alone were to be relied upon. Ignacy Hryniewiecki (Ignaty Grinevitsky), Nikolai Rysakov, Timofey Mikhailov, and Ivan Yemelyanov had volunteered as bomb-throwers.[3][1]

The group opened a cheese store in the Eliseyev Emporium on Malaya Sadovaya Street, and used one of the rooms to dig a tunnel extending to the middle of the street, where they would lay large quantities of dynamite. The hand-held bombs were designed and manufactured chiefly by Nikolai Kibalchich. The night before the attack, Perovskaya along with Vera Figner (also one of seven women on the Executive Committee) helped assemble the bombs.[1][2]

Zhelyabov was to have directed the bombing, and he was supposed to assail Alexander II with dagger or pistol in case both the mine and the bombs were unsuccessful. When Zhelyabov was arrested two days prior to the attack, his wife Sophia Perovskaya took the reins.[4]

-

Andrei Zhelyabov (tried and hanged)

-

Sophia Perovskaya (tried and hanged)

-

Nikolai Rysakov (tried and hanged)

-

Ignacy Hryniewiecki (died of wounds from the 2nd explosion)

-

Ivan Yemelyanov (20 years in prison; pardoned)

-

Nikolai Kibalchich (tried and hanged)

-

Timofey Mikhailov (tried and hanged)

-

Hesya Helfman (died in prison after childbirth 1882)

-

Nikolai Sablin (committed suicide)

-

Vera Figner (20 years in prison; pardoned)

Assassination[edit]

The Tsar travelled both to and from the Manège in a closed two-seater carriage drawn by a pair of horses. He was accompanied by five mounted Cossacks and Frank (Franciszek) Joseph Jackowski, a Polish noble, with a sixth Cossack sitting on the coachman's left. The emperor's carriage was followed by three sleighs carrying, among others, the chief of police Colonel Dvorzhitzky and two officers of the Gendarmerie.[3]

On the afternoon of 13 March, after having watched the manoeuvres of two Guard battalions at the Manège, the Tsar's carriage turned into Bolshaya Italyanskaya Street, thus avoiding the mine in Malaya Sadovaya. Perovskaya, by taking out a handkerchief and blowing her nose as a predetermined signal, dispatched the assassins to the Canal. On his way back, the Tsar also decided to pay a brief visit to his cousin, the Grand Duchess Catherine. This gave the bombers ample time to reach the Canal on foot; with the exception of Mikhailov, they all took up their new positions.[5]

At 2:15 PM, the carriage had gone about 150 yards down the quay when it encountered Rysakov who was carrying a bomb wrapped in a handkerchief. On the signal being given by Perovskaya, Rysakov threw the bomb under the Tsar's carriage. The Cossack who rode behind (Alexander Maleichev) was mortally wounded and died later that day. Among those injured was a fourteen year old peasant boy (Nikolai Zakharov) who served as a delivery boy in a butcher's shop. However, the explosion had only damaged the bulletproof carriage. The emperor emerged shaken but unhurt. Rysakov was captured almost immediately. Police Chief Dvorzhitsky heard Rysakov shout out to someone else in the gathering crowd. The coachman implored the Emperor not to alight. Dvorzhitzky offered to drive the Tsar back to the Palace in his sleigh. The Tsar agreed, but he decided to first see the culprit, and to survey the damage. He expressed solicitude for the victims. To the anxious inquires of his entourage, Alexander replied, "Thank God, I'm untouched".[3][6][7]

He was ready to drive away when a second bomber, Hryniewiecki, who had come close to the Tsar, made a sudden movement, throwing a bomb at his feet. A second explosion ripped through the air and the Emperor and his assassin fell to the ground, both mortally injured. Since people had crowded close to the Tsar, Hryniewiecki's bomb claimed more injuries than the first (according to Dvorzhitsky, who was himself injured, there were about 20 people with wounds of varying degree). Alexander was leaning on his right arm. His legs were shattered below the knee from which he was bleeding profusely, his abdomen was torn open, and his face was mutilated. Hryniewiecki himself, also gravely wounded from the blast, lay next to the Tsar and the butcher's boy.[3][8]

Ivan Yemelyanov, the third bomber in the crowd, stood ready, clutching a briefcase containing a bomb that would be used if the other two bombers failed. However, he and other bystanders rushed to answer the Tsar's barely audible cries for help; he could barely whisper: "Take me to the palace... there... I will die."[7][9] Alexander was carried by sleigh to his study in the Winter Palace, where almost the same day twenty years earlier, he had signed the Emancipation Edict freeing the serfs. Members of the Romanov family came rushing to the scene. The dying emperor was given Communion and Last rites. When the attending physician, Sergey Botkin, was asked how long it would be, he replied, "Up to fifteen minutes." At 3:30 PM that day, the personal flag of Alexander II was lowered for the last time.[10]

Arrests, trials, and punishments[edit]

The thrower of the fatal second bomb, Hryniewiecki, was carried to the military hospital nearby, where he lingered in agony for several hours. Refusing to cooperate with the authorities or even to give his name, he died that evening.[6] In a vain attempt to save his own life, Rysakov, the first bomb-thrower who had been captured at the scene, cooperated with the investigators. His testimony implicated the other participants, and enabled the police to raid the group's headquarters. The raid took place on 15 March, two days after the assassination. Helfman was arrested and Sablin fired several shots at the police and then shot himself to avoid capture. Mikhailov was captured in the same building the next day after a brief gunfight. The tsarist police apprehended Sophia Perovskaya on 22 March, Nikolai Kibalchich on 29 March, and Ivan Yemelyanov on 14 April.[3][11]

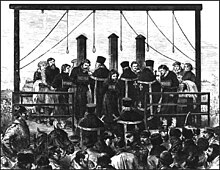

Zhelyabov, Perovskaya, Kibalchich, Helfman, Mikhailov, and Rysakov were tried as State criminals by the Special Tribunal of the Ruling Senate on 26–29 March and sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence was duly carried out on 15 April 1881. In the case of Hesya Helfman, her execution was deferred on account of her pregnancy.[12][14] Alexander III later commuted her sentence of death to katorga (forced labor) for an indefinite period of time. She died of a post-natal complication in January 1882, and her infant daughter did not survive much longer.[15]

Yemelyanov was tried the following year and was sentenced to life imprisonment at hard labor; however, he received a pardon from the Tsar after serving 20 years.[3] Vera Figner remained at large until 10 February 1883; during this time she orchestrated the assassination of General Mayor Strelnikov, the military prosecutor of Odessa. In 1884, Figner was sentenced to die by hanging which was then commuted to indefinite penal servitude. She likewise served for 20 years until a plea from her dying mother persuaded the last tsar, Nicholas II, to set her free.[2][16]

Burial[edit]

A temporary shrine was erected on the site of the attack while plans and fundraising for a more permanent memorial were undertaken. The permanent memorial took the form of the Church of the Savior on Blood. Construction began in 1883 under Alexander III, and was completed in 1907 under Nicholas II. An elaborate shrine, in the form of a ciborium, was constructed at the end of the church opposite the altar, on the exact place of Alexander's assassination. It is embellished with topaz, lazurite, and other semi-precious stones, making a striking contrast with the simple cobblestones of the old road, which are exposed in the floor of the shrine.[17]

Aftermath for Jews[edit]

Alexander II was seen as tolerant towards Jews. During his reign, special taxes on Jews were eliminated and those who graduated from secondary school were permitted to live outside the Pale of Settlement, and became eligible for state employment. Large numbers of educated Jews moved as soon as possible to Moscow, Saint Petersburg, and other major cities.[18][19] Alexander III, who succeeded his father after his assassination, reversed this trend.

The importance of Hesya Helfman's role in the assassination was undetermined, and her Jewish origins stressed.[20][21] Another conspirator, Ignacy Hryniewiecki, was also rumoured to be Jewish, though there seems to have been no basis for this. In the aftermath of the assassination, the May Laws were passed. The assassination also inspired retaliatory attacks on Jewish communities. During these pogroms, thousands of Jewish homes were destroyed; many families were reduced to poverty and large numbers of men, women and children were injured or killed in 166 towns in the south-western provinces of the Empire

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 273.

- ^ a b c Kirschenbaum 2014, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f g Kel'ner 2015.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 276.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 278.

- ^ a b Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 280.

- ^ a b Hartnett 2001, p. 251.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 279.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 281.

- ^ Radzinsky 2005, p. 419.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 283.

- ^ a b EXECUTION OF THE CZAR'S ASSASSINS.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 307.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 288.

- ^ Yarmolinsky 2016, p. 287.

- ^ Hartnett 2001, p. 255.

- ^ SacredDestinations.

- ^ Karesh, Sara E.; Hurvitz, Mitchell M. (2005). Encyclopedia of Judaism. Infobase. pp. 10–11. ISBN 9780816069828.

- ^ James P. Duffy, Vincent L. Ricci, Czars: Russia's Rulers for Over One Thousand Years, p. 324

- ^ Jewish Chronicle, 6 May 1881; quoted in Benjamin Blech, Eyewitness to Jewish History.

- ^ Hertz, Deborah (2014). "Dangerous Politics, Dangerous Liaisons: Love and Terror among Jewish Women Radicals in Czarist Russia". Histoire, économie & société. 33 (4): 99–100. doi:10.3917/hes.144.0094. ISSN 0752-5702.

Bibliography[edit]

- Yarmolinsky, Avrahm (2016). Road to Revolution: A Century of Russian Radicalism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691638546.

- Kel'ner, Viktor Efimovich (2015). 1 marta 1881 goda: Kazn imperatora Aleksandra II (1 марта 1881 года: Казнь императора Александра II). Lenizdat. ISBN 978-5-289-01024-7.

- Radzinsky, Edvard (2005). Alexander II: The Last Great Czar. Freepress. ISBN 978-0743284264.

- "Church of the Savior on Blood, St. Petersburg". Sacred Destinations. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- Hartnett, L. (2001). "The Making of a Revolutionary Icon: Vera Nikolaevna Figner and the People's Will in the Wake of the Assassination of Tsar Aleksandr II". Canadian Slavonic Papers. 43 (2/3): 249–270. doi:10.1080/00085006.2001.11092282. JSTOR 40870322. S2CID 108709808.

- Kirschenbaum, Lisa A. (2014). "The Noble Terrorist". The Women's Review of Books. 31 (5): 12–13. JSTOR 24430570.

- "Execution of the Czar's Assassins". Australian Town and Country Journal (Sydney, NSW : 1870–1907). 4 June 1881. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- 1880s in Saint Petersburg

- 1881 in the Russian Empire

- 1881 murders in the Russian Empire

- Alexander II of Russia

- Assassinations in the Russian Empire

- Deaths by person in the Russian Empire

- Deaths by suicide bomber

- Deaths from bleeding

- March 1881 events

- Murder in the Russian Empire

- Narodnaya Volya

- Russian Empire regicides

- Suicide bombings in Russia

- Terrorism in the Russian Empire

- Terrorist incidents in Saint Petersburg