Athanasios Diakos

General Athanasios Diakos Αθανάσιος Διάκος | |

|---|---|

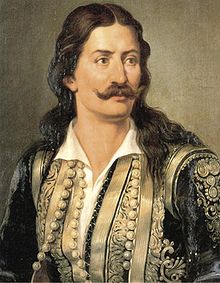

Portrait by Dionysios Tsokos | |

| Native name | Αθανάσιος Νικόλαος Μασσαβέτας |

| Birth name | Athanasios Nikolaos Massavetas |

| Nickname(s) | Diakos (Deacon) Διάκος |

| Born | 1788 or 1791[1] Ano Mousounitsa or Artotina, Ottoman Empire (now Greece) |

| Died | 24 April 1821 (aged 30 or 33) Lamia, Ottoman Empire (now Greece) |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1821 |

| Rank | General (posthumously) |

| Commands held | Commander of his armed band |

| Wars | |

| Memorials | Athanasios Diakos (village) and others |

| Other work | Monk Member of the Filiki Etaireia |

Athanasios Nikolaos Massavetas or Grammatikos (Greek: Αθανάσιος Νικόλαος Μασσαβέτας-Γραμματικός; 1788 – 24 April 1821) also known as Athanasios Diakos (Greek: Αθανάσιος Διάκος) was a Greek military commander during the Greek War of Independence, considered a venerable national hero in Greece.

Early life[edit]

Athanasios Nikolaos was born in Phocis, in the village of Ano Mousounitsa, or according to other sources in nearby Artotina. His family's surname was originally either "Grammatikos"[2][3][4][5] or "Massavetas".[6] The grandson of a local outlaw, or klepht, he was drawn to religion from an early age and was sent away by his parents to the Monastery of St. John the Baptist (Greek: Αγίου Ιωάννου Προδρόμου), near Artotina, for his education. He became a monk at the age of seventeen and, due to his devotion to his faith and good temperament, was ordained a Greek Orthodox deacon not long afterwards.[7]

Popular tradition has it that while at the monastery, an Ottoman Pasha visited with his troops and was impressed by Athanasios's good looks. The young Athanasios took offence to the Turk's remarks (and subsequent proposal) and the ensuing altercation resulted in the death of the Turkish official. Athanasios was forced to flee into the nearby mountains and become a klepht. Soon afterwards he adopted the pseudonym "Diakos", or Deacon.[citation needed]

Klepht and Armatolos[edit]

Diakos served under a number of local klepht leaders in the region of Roumeli, distinguishing himself in various encounters with the Ottomans. He also served for a time as a mercenary in the army of Ali Pasha of Ioannina in Epirus, where he befriended Odysseas Androutsos, another klepht. When Androutsos became the captain of a unit of armatoloi at Livadeia, Diakos served for a time as his protopallikaro (literally "first warrior", or lieutenant). In the years leading up to the Greek War of Independence, Diakos had formed his own band of klephtes and, like many other klepht and armatoloi captains, he had become a member of the Filiki Eteria.[8]

Independence fighter[edit]

Soon after the outbreak of hostilities, Diakos and a local brigand captain and friend, Vasilis Bousgos, led a contingent of fighters to capture the town of Livadeia. On 1 April 1821, after three days of vicious house-by-house fighting, and the burning of Mir Aga's residence, including the harem, the Greeks liberated the town. Hursid Pasha sent two of his most competent commanders from Thessaly, Omer Vryonis and Köse Mehmed, at the head of 8,000 men with orders to put down the revolt in Roumeli and then proceed to the Peloponnese and lift the siege at Tripolitsa.[9]

Diakos and his band, reinforced by the fighters of Dimitrios Panourgias and Yiannis Dyovouniotis, decided to halt the Ottoman advance into Roumeli by taking defensive positions near Thermopylae. The Greek force of 1,500 men was split into three sections. Dyovouniotis was to defend the bridge at Gorgopotamos, Panourgias the heights of Halkomata, and Diakos the bridge at Alamana.[10]

Setting out from their camp at Lianokladi, near Lamia, the Ottoman Turks soon divided their force. The main force attacked Diakos. The other attacked Dyovouniotis, whose force was quickly routed, and then Panourgias, whose men retreated when he was wounded. The majority of the Greek force having fled, the Ottomans concentrated their attack on Diakos's position at the Alamana bridge.[11] Seeing that it was a matter of time before they were overrun by the enemy, Bousgos, who had been fighting alongside Diakos, pleaded with him to retreat to safety. Diakos chose to stay and fight with 48 men; they put up a desperate hand-to-hand struggle for a number of hours before being overwhelmed.[12]

The severely wounded Diakos was taken before Vryonis, who offered to make him an officer in the Ottoman Army if he converted from Christianity to Islam. Diakos refused the offer, replying "I was born a Greek, I shall die a Greek" ("Εγώ Γραικός γεννήθηκα, Γραικός θε να πεθάνω" transliterated as: Ego Grekos gennithika, Grekos the na pethano). The next day he was impaled. According to popular tradition, as he was being led away to be executed, he said:

Poetic: Oh, what a moment Death chose for me to perish. Spring grass everywhere and branches with blossoms to cherish. Literally: Look at the time Charon chose to take me, now that the branches are flowering, and the earth sends forth grass (Greek: Για δες καιρό που διάλεξε ο Χάρος να με πάρει, τώρα π'ανθίζουν τα κλαριά και βγάνει η γης χορτάρι - Gia des kero pou dialexe o Haros na me parei, tora p'anthizoun ta klaria ke vganei i gis hortari).

This was a metaphor for the independence and freedom of Greece.

The brutal manner[13] of Diakos's death initially struck fear into the populace of Roumeli, but his final stand near Thermopylae, echoing the heroic defence of the Spartan King Leonidas, made him a martyr for the Greek cause. A monument now stands at the bridge near Alamana, the site of his final battle. His alleged birthplace, the village of Ano Mousounitsa, was later renamed Athanasios Diakos in his honour. The Greek Army honoured him with the rank of general. Also streets and statues in several parts of Greece as well as in nearly every one of the larger towns and cities bear his name.[14]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Bopis, Dimitris (2007). "Αθανάσιος Διάκος, ο πρώτος μάρτυρας του αγώνα" [Athanasios Diakos, the first martyr of the struggle]. Στρατιωτική Ιστορία ("Military History") (in Greek). Περισκόπιο ("Periskopio") (128): 11.

- ^ Μπόπης, Δημήτριος (April 2007). "ΑΘΑΝΑΣΙΟΣ ΔΙΑΚΟΣ - Ο πρώτος μάρτυρας του Αγώνα". ΣΤΡΑΤΙΩΤΙΚΗ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ.

- ^ Παππάς, Ευάγγελος (2014). Το συναξάρι του Μεγαλομάρτυρα Αθανασίου Διάκου. Αθήνα. p. 88. ISBN 978-960-696-159-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Μελάς, Λέων Αγαπητός, Αγαπητός Γούδας, Αναστάσιος Φόρτης, Σπ. Γ. Συλλογικό έργο, Μελάς, Λέων Αγαπητός, Αγαπητός Γούδας, Αναστάσιος Φόρτης, Σπ. Γ. Συλλογικό έργο (2009). Άπαντα για τον Αθ. Διάκο. Αττική: Μέρμηγκας. p. 192. ISBN 978-960-87909-3-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Γούδας, Αναστάσιος (2004). Σουλιώτες και Ρουμελιώτες καπεταναίοι του 1821. Αττική: Βεργίνα. p. 221. ISBN 960-86360-2-7.

- ^ «Πού εγεννήθη ο Αθανάσιος Διάκος» Archived 2009-05-23 at the Wayback Machine, Μελέτη Κων. Παπαχρήστου

- ^ "Διάκος, Αθανάσιος (Μουσουνίτσα Παρνασσίδας, 1786 - Λαμία, 1821)". Παγκόσμιο Βιογραφικό Λεξικό - Τόμος: 3. Εκδοτική Αθηνών. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ "Διάκος, Αθανάσιος (Μουσουνίτσα Παρνασσίδας, 1786 - Λαμία, 1821)". Παγκόσμιο Βιογραφικό Λεξικό - Τόμος: 3. Εκδοτική Αθηνών. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Bopis, Dimitris (2007). "Αθανάσιος Διάκος, ο πρώτος μάρτυρας του αγώνα" [Athanasios Diakos, the first martyr of the struggle]. Στρατιωτική Ιστορία ("Military History") (in Greek). Περισκόπιο ("Periskopio") (128): 15–17.

- ^ Bopis, Dimitris (2007). "Αθανάσιος Διάκος, ο πρώτος μάρτυρας του αγώνα" [Athanasios Diakos, the first martyr of the struggle]. Στρατιωτική Ιστορία ("Military History") (in Greek). Περισκόπιο ("Periskopio") (128): 17–18.

- ^ "Διάκος, Αθανάσιος (Μουσουνίτσα Παρνασσίδας, 1786 - Λαμία, 1821)". Παγκόσμιο Βιογραφικό Λεξικό - Τόμος: 3. Εκδοτική Αθηνών. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ Bopis, Dimitris (2007). "Αθανάσιος Διάκος, ο πρώτος μάρτυρας του αγώνα" [Athanasios Diakos, the first martyr of the struggle]. Στρατιωτική Ιστορία ("Military History") (in Greek). Περισκόπιο ("Periskopio") (128): 18.

- ^ Aiolos (2004), "Turkish Culture: The Art of Impalement", Hellenic Lines: The National conservative newspaper, archived from the original on 25 May 2011, retrieved 9 March 2011

- ^ Bopis, Dimitris (2007). "Αθανάσιος Διάκος, ο πρώτος μάρτυρας του αγώνα" [Athanasios Diakos, the first martyr of the struggle]. Στρατιωτική Ιστορία ("Military History") (in Greek). Περισκόπιο ("Periskopio") (128): 19.

General bibliography[edit]

- Bopis, Dimitris (2007). "Αθανάσιος Διάκος, ο πρώτος μάρτυρας του αγώνα" [Athanasios Diakos, the first martyr of the struggle]. Στρατιωτική Ιστορία ("Military History") (in Greek). Περισκόπιο ("Periskopio") (128): 10–19.

- Brewer, David. The Greek War of Independence. The Overlook Press (2001). ISBN 1-58567-172-X.

- Diamantopoulos, N. and Kyriazopoulou, A. Elliniki Istoria Ton Neoteron Hronon. OEDB, (1980).

- Paroulakis, Peter H. The Greeks: Their Struggle For Independence. Hellenic International Press (1984). ISBN 0-9590894-1-1.

- Stratiki, Poti. To Athanato 1821. Stratikis Bros, (1990). ISBN 960-7261-50-X.

External links[edit]

- Athanasios Diakos Museum at Athanasios Diakos, Phocis, Greece (in Greek)

- 1788 births

- 1821 deaths

- 19th-century executions by the Ottoman Empire

- Armed priests

- Christians executed for refusing to convert to Islam

- Executed Greek people

- Executed revolutionaries

- Greek Christian monks

- Greek generals

- Greek military leaders of the Greek War of Independence

- Greek torture victims

- People executed by impalement

- People from Kallieis

- People from Phocis