Cippi of Melqart

| The Cippi of Melqart | |

|---|---|

The two Cippi of Melqart, reunited in Doha in 2023. | |

| Material | White marble |

| Size | 1.05m x 0.34m x 0.31m |

| Writing | Greek script and ancient Phoenician alphabet |

| Created | Early Roman era (2nd century BC) |

| Discovered | 17th century, undocumented circumstances |

| Present location | National Museum of Archaeology (Malta Cippus) and, Sully wing, Ground floor, Mediterranean world, Room 18b, at the Louvre Museum[1][2] (Louvre Cippus) |

| Registration | CIS I, 122/122 bis or KAI 47 (Malta Cippus), AO 4818 (Louvre Cippus) |

The Cippi of Melqart are a pair of Phoenician marble cippi that were unearthed in Malta under undocumented circumstances and dated to the 2nd century BC. These are votive offerings to the god Melqart, and are inscribed in two languages, Ancient Greek and Phoenician, and in the two corresponding scripts, the Greek and the Phoenician alphabet. They were discovered in the late 17th century, and the identification of their inscription in a letter dated 1694 made them the first Phoenician writing to be identified and published in modern times.[3] Because they present essentially the same text (with some minor differences), the cippi provided the key to the modern understanding of the Phoenician language. In 1758, the French scholar Jean-Jacques Barthélémy relied on their inscription, which used 17[n 1] of the 22 letters of the Phoenician alphabet, to decipher the unknown language.

The tradition that the cippi were found in Marsaxlokk was only inferred by their dedication to Heracles,[n 2] whose temple in Malta had long been identified with the remains at Tas-Silġ.[n 3] The Grand Master of the Order of the Knights Hospitaller, Fra Emmanuel de Rohan-Polduc, presented one of the cippi to the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres in 1782.[6] This cippus is currently in the Louvre Museum in Paris, while the other rests in the National Museum of Archaeology in Valletta, Malta. The inscription is known as KAI 47.

Description and history[edit]

The importance of the cippi to Maltese archaeology is inestimable.[5] On an international level, they already played a significant role in the deciphering and study of the Phoenician language in the 18th and 19th centuries.[5][7] Such was their importance to Phoenician and Punic philology, that the inscriptions on the cippi became known as the Inscriptio melitensis prima bilinguis (Latin for First bilingual Maltese inscription), or the Melitensis prima (First Maltese).[8]

A cippus (plural cippi) is a small column. Cippi serve as milestones, funerary monuments, markers, or votive offerings.[9] The earliest cippi had a cubic shape and were carved from sandstone. By the late fifth century BC, these became gabled delicate stelae in the Greek fashion.[10] The Maltese marble cippus is about 96.52 centimetres (38 in) high at the highest point, and is broken at the top.[11] The Louvre Cippus is currently 1.05 metres (3 ft 5 in) high at its highest point, 0.34 m (1 ft 1 in) wide, and 0.31 m (1 ft 0 in) thick.[2] "Their form is light and gracefully executed ..." with a " ...Greek inscription upon the pedestal, [and] a masterpiece of Phoenician epigraphy."[11] The artifacts are carved in white marble, a stone which is not found naturally in the Maltese islands.[5] As it is unlikely that skilled marble-carvers were available, they were probably imported in their finished state.[5] The inscriptions, however, were probably engraved in Malta on behalf of the two patrons, Abdosir and Osirxamar. Judging by the names on the main inscription, the patrons were of Tyrian extraction. The addition of a synopsis of the dedication in Greek, with the names of the dedicators and of Melqart given in their Hellenised versions, confirms the existence and influence of Hellenistic culture.[5] Additionally, while Malta had been colonised by the Phoenicians since the 8th century BC, by the second century, the Maltese islands were under Roman occupation.[2][12] The use of Phoenician script also confirms the survival of Phoenician culture and religion on the islands.[n 4]

Although it is not rare for cippi to have dedications,[14] the Cippi of Melqart have an unusual construction, as they have two parts. The base, or pedestal, is a rectangular block with mouldings at the top and bottom.[2] The inscriptions in Greek and Phoenician are at the front, three lines in Greek and four in Phoenician. The inscriptions are lightly incised.[2] The bases support pillars which are interpreted as candelabra. The lower parts of the candelabra are decorated with a shallow relief of acanthus leaves. Calligraphic differences in the incised text, varying positioning of the words and differences in the depth of the relief and the mouldings, imply that the two cippi are separate offerings, carrying the same inscription because the patrons were brothers.[n 5]

When the Greek inscription was published in the third volume of the Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum in 1853, the cippi were described as discovered in the coastal village of Marsaxlokk.[15] Before, their Marsaxlokk provenance had not been proposed by anyone, and it was more than a century later that the claim was discredited.[16] The attribution to Tas-Silġ was apparently reached by inference, because the candelabra were thought, with some plausibility, to have been dedicated and set up inside the temple of Heracles.[5][n 6][18]

Inscriptions on the Cippi[edit]

The Phoenician inscription is a Phoenician votive inscription to Melqart, and it reads (from right to left;[n 7] characters inside brackets denote a filled in lacuna):

𐤋𐤀𐤃𐤍𐤍

lʾdnn

𐤋𐤌𐤋𐤒𐤓𐤕

lmlqrt

𐤁𐤏𐤋

bʿl

𐤑𐤓

ṣr

𐤀𐤔

ʾš

𐤍𐤃𐤓

ndr

To our lord Melqart, Lord of Tyre, dedicated by

𐤏𐤁𐤃[𐤊]

ʿbd[k]

𐤏𐤁𐤃𐤀𐤎𐤓

ʿbdʾsr

𐤅𐤀𐤇𐤉

wʾḥy

𐤀𐤎𐤓𐤔𐤌𐤓

ʾsršmr

you[r] servant Abd' Osir and his brother 'Osirshamar

𐤔𐤍

šn

𐤁𐤍

bn

𐤀𐤎𐤓𐤔𐤌𐤓

ʾsršmr

𐤁𐤍

bn

𐤏𐤁𐤃𐤀𐤎𐤓

ʿbdʾsr

𐤊𐤔𐤌𐤏

kšmʿ

both sons of 'Osirshamar, son of Abd' Osir, for he heard

The following is the Greek inscription, a rendering to polytonic and bicameral script and adding spaces, a transliteration including accents, and a translation:

Διονύσιος

Dionýsios

καὶ

kaì

Σαραπίων

Sarapíōn

οἱ

hoi

Dionysios and Sarapion, the

Σαραπίωνος

Sarapíōnos

Τύριοι

Týrioi

sons of Sarapion, Tyrenes,

Discovery and publication[edit]

Initial identification[edit]

In 1694, a Maltese canonicus, Ignazio di Costanzo, was the first to report an inscription on the cippi which he considered to be in the Phoenician language.[20] This identification was on the basis that "Phoenicians" were recorded as ancient inhabitants of Malta by Greek writers Thucydides and Diodorus Siculus.[n 10] Costanzo spotted these inscriptions, which were part of two almost identical votive cippi at the entrance of Villa Abela in Marsa, the house of the celebrated Maltese historian, Gian Franġisk Abela.[4] [n 11] Di Costanzo immediately recognised the Greek inscriptions, and he thought the other parts were written in Phoenician.[n 12] However, the Maltese historian Ciantar claimed that the cippi were discovered in 1732, and placed the discovery in the villa of Abela, which had become a museum entrusted to the Jesuits.[n 13] The contradiction in the dates of the discovery is confusing, given di Costanzo's 1694 letter.[5]

Ignazio Paternò, prince of Biscari, reports another story regarding their discovery. Paternò describes how two candelabri were stored at the Bibliotecha, after they had been found on the island of Gozo.[24] Paternò attributes the discovery to Fr. Anton Maria Lupi, who had found the two votive cippi with the Phoenician inscriptions abandoned in a villa owned by the Jesuit Order in Gozo, linking them with the cippi mentioned by Ciantar.[24][n 14]

Copies of the inscriptions, which had been made by Giovanni Uvit in 1687, were sent to Verona to an art historian, poet and Knight Commander in the Hospitaller order, Bartolomeo dal Pozzo.[20] These were then handed to another Veronese noble art collector, Francesco Sparaviero who wrote a translation of the Greek section.[n 15]

In 1753, Abbé Guyot de Marne, also a Knight Commander of the Maltese Order, published the text again in an Italian journal, the Saggi di dissertazioni accademiche of the Etruscan Academy of Cortona, but did not hypothesise a translation.[25] The first attempt had come in 1741, by the French scholar Michel Fourmont, who had published his assumptions in the same journal.[4] However, neither led to a useful translation.[26]

Deciphering the Phoenician script[edit]

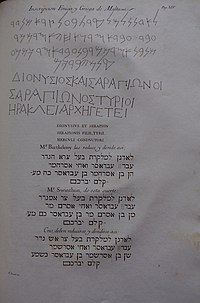

The shorter Phoenician text was transliterated and translated more than twenty years after Fourmont's publication, by the Abbé Jean-Jacques Barthélemy.[2] Barthélemy, who had already translated Palmyrene, submitted his work in 1758.[27]

He correctly identified 16 of the 17 different letters represented in the text, but still mistook the Shin and the He.[4] Barthélémy began the translation of the script by reading the first word "lʾdnn" as "to our lord."[27] The hypothesis that Heracles corresponded with Melqart, Lord of Tyre, made Barthélemy pinpoint more letters, while the names of the patrons, being the sons of the same father in the Greek text, allowed the backward induction of the father's name in the Phoenician text.[2]

The Phoenician script, once translated read:

- "To our lord Melqart, Lord of Tyre, dedicated by / your servant Abd' Osir and his brother 'Osirshamar / both sons of 'Osirshamar, son of Abd' Osir, for he heard / their voice, may he bless them."[2][n 8]

The paleographic table published by Barthélémy lacked the letters Tet and Pe.[4] The study of the Phoenician inscription on the base of the Louvre cippus can be regarded as the true foundation of Phoenician and Punic studies, at a time when the Phoenicians and their civilisation were known only through classical or Biblical texts.[4]

Later work[edit]

Work on the cippi now focused on a fuller understanding of Phoenician grammar, as well as the implications of the discovery of Phoenician texts in Malta. Johann Joachim Bellermann believed that the Maltese language was a distant descendant of Punic.[28] This was refuted by Wilhelm Gesenius, who like Abela before him, held that Maltese was a dialect of Arabic.[4] Further studies on the Melitensis prima text followed developments in the study of Phoenician grammar, comparing Punic specimens closely with Hebrew texts.[4] In 1772, Francisco Pérez Bayer published a book detailing the previous attempts at understanding the text, and provided his own interpretation and translation.[29]

In 1782, Emmanuel de Rohan-Polduc, Grand Master of the Order of Malta, presented one of the cippi to the Académie des Inscriptions et des Belles Lettres.[6][30] The cippus was moved to the Bibliothèque Mazarine between 1792 and 1796.[2] In 1864, the orientalist Silvestre de Sacy, suggested that the French cippus should be moved to the Louvre.[2]

Idiomatic use and cultural impact[edit]

The term Rosetta stone of Malta has been used idiomatically to represent the role played by the cippi in decrypting the Phoenician alphabet and language.[7][31] The cippi themselves became a treasured symbol of Malta.[32] Their image has appeared on local postage stamps,[33] and hand-crafted models of the artifacts have been presented to visiting dignitaries.[34]

The two cippi were reunited for the first time in 240 years at an exhibition at the Louvre Abu Dhabi in 2023.[35]

Notes and references[edit]

Notes

- ^ The description of the Louvre cippus states that the inscription contains 18 out of the 22 letters in the Phoenician alphabet.[2] Lehmann, however, reports that there are 17.[4] The latter source appears to be more credible (Lehmann cites the cippi's lack of a proper provenance, while the Louvre collection states the cippi were found at Marsaxlokk).

- ^ The Phoenician god Melqart was associated with the Hellenic god Heracles by means of interpretatio graeca.

- ^ " Corpus Inscriptionum Græcarum vol. 3, no. 5733, 680‒681 " - (in Latin and Greek) "Ambo simul monumenta sunt reperta inter rudera, etiam nunc exstantia, portus hodie Marsa Scirocco, olim Ἡρακλέουϛ λιµήν, appellati".[5]

- ^ (in French) "...en plein période dite 'punicò-romaine' (II siècle av. J.-C.), des Maltais restent Phéniciens, attachés à la religion et à la culture phéniciennes."[13]

- ^ (in French) "...deux monuments distincts, chacun étant l’oeuvre d’un artisan et d’un scribe différents."[13]

- ^ Μελίτη νῆσος ἐν ᾗ ... καὶ Ἡρακλέους ἱερόν. The island of Melite on which is ... and the temple of Heracles.[17]

- ^ Unfortunately the rendered direction of the Phoenician text may vary across web browsers. See relevant talk page section.

- ^ a b Important Note: As of 25 February 2014, in the Louvre Museum webpage of the Cippus,[2] the text in bold below is missing from the translation of the third line of the Phoenician inscription:

both sons of 'Osirshamar, for he heard for both sons of 'Osirshamar, son of Abd' Osir, for he heard. - ^ Apart from the aforementioned association and hence change from Melqart to Heracles, the (theophoric) names of the two brothers and of their father and grandfather themselves change form between the inscribed languages, according to a form of interpretatio graeca, showing the great degree of cultural syncretism characteristic of the Hellenistic age, including in this case, Egypt:

Abd' Osir, "Servant of Osiris" and 'Osirshamar, "Osiris has guarded" or "Osiris has preserved", become respectively, Dionysios, a name derived from Dionysos, and Sarapion, a name derived from Serapis.[19] - ^ (in Italian) "Stimo esser stata simile lamina, qualche superstitioso Amuleto posto presso quel cadavere, ivi esistente per poco meno di tre mila anni, mentre da Geroglifìci Egytii, e da quei segni di caratteri posti su'l fine della prima linea scorgonsi in essa, da me giudicati per Fenici, si riconosce esser stato questo amuleo di personaggio Fenice, la di cui natio ne hebbe ne'trasandati tempo per piu secoli il dominio di quest'isola, conforme l'afferma Tucidide... E Diodoro Sicolo, parlando delle Colonie de Fenici, e commentando il detto testo di Tucidide, lasciò scritto...".[20]

- ^ The villa was demolished by the British colonial administration to build a power station.[21]

- ^ (in Italian) "Due iscrittioni scolpite con caratteri Greci, e Fenici a mio credere".[20]

- ^ (in Italian) "L’anno 1732 essendo Rettore di questo collegio de’ Padri Gesuiti il P. Ignazio Bonanno si scavò parte d’un viale del Giardino, in cui è situato il sovraccennato casino, posseduto un tempo dall’Abela, che scriveva l’anno 1647, per fabbricarvi una scala; e quivi sotterrate si rinvennero le due Pietre co’ Fenici, e Greci caratteri segnate; le quali dal P. Luigi Duquait Francese sovrastante all’opera furon collocate nello stesso viale per ornamento. Dopo qualche tempo un altro accorto Religioso temendo, che di là tolte fossero (come fu lor tolto il capo della bella statua d’Ercole, che fu venduto per testa di S. Giuseppe, e poi da essi ricuperato, e riunito al suo luogo) trasportolle alla stanza contigua al Gabinetto, o Museo dell’Abela".[22] The episode is referred to briefly in Abela-Ciantar, vol. I, p. 465, and in further detail on pp. 527-528.[23]

- ^ (in Italian) "Mi fu detto che nella Villetta del Collegio vi erano due Iscrizioni Arabiche sotto due balaustretti. Io ero stato alla Villa ed avevo visto i balaustri asserti; ma come essi sono vicini a terra sopra di un muricciolo al Sole, non avevo fatto altra riflessione sopra di essi, nè ve l'aveva fatta niuno, se non che poco eruditamente chi me ne diè notizia. Presi aldunque la barchetta, e là tornai, e trovai due iscrizioni non altrimente Arabiche, ma Fenicie e Greche; e dal tenore della Greca, che è in tutti due i dadi la stessa, credo, che i balaustrelli fossero due Candelabri rotti, offerti in dono ad Ercole Arcbagete, da due fratelli di Tiro in Fenicia. A buon conto abbiamo questo nome di Ercole, che io non so se ha noto altrove". Lupi let.11 s.64.[24]

- ^ (in Italian) "[…] che tralasciatane la discifratione di quei caratteri stimati Fenici, per essere forse a lui ignoti, mit trasmise la seguente spiegatione delli Greci in esse tavole scolpiti. Dionysius et Sarapion Sarapionis Tirii, Herculi Duci".[20]

References

- ^ AO 4818: Room 18b. Mattmann, Philippe (2013). Near Eastern Antiquities. Visit the Louvre With the Bible. www.louvrebible.org. ISBN 979-10-92487-05-3.[permanent dead link] At Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Cippus from Malta". Louvre Museum. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ^ Lehmann, p210 and 257, quote: "Soon thereafter, at the end of the 17th century, the abovementioned Ignazio di Costanzo was the first to report a Phoenician inscription and to consciously recognize Phoenician characters proper... And just as the Melitensis prima inscription played a prominent part as the first-ever published Phoenician inscription... and remained the number-one-inscription in the Monumenta (fig. 8), it now became the specimen of authentic Phoenician script par excellence... The Melitensis prima inscription of Marsa Scirocco (Marsaxlokk) had its lasting prominence as the palaeographic benchmark for the assumed, or rather deduced “classical” Phoenician (“echtphönikische”) script."

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lehmann, Reinhard G. (2013). "Wilhelm Gesenius and the Rise of Phoenician Philology" (PDF). Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft. 427. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter GmbH. ISBN 978-3-11-026612-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2014-02-21. At the Forschungsstelle für Althebräische Sprache und Epigraphik, University of Mainz.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bonanno, Anthony (1982). "Quintinius and the location of the Temple of Hercules at Marsaxlokk". Melita Historica. 8 (3): 190–204.

- ^ a b Berger, Philippe (1888). "L'histoire d'une inscription. Une rectification au Corpus inscriptionum semiticarum, 1ère partie, n°122". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 32 (6). PERSEE Program: 494–500. doi:10.3406/crai.1888.69568. ISSN 0065-0536.

- ^ a b Castillo, D. (2006). The Maltese Cross: A Strategic History of Malta. Contributions in Military Studies. Westport: Praeger Security International. p. 18. ISBN 0313323291. At Google Books.

- ^ Wilhelm Gesenius (1837). Scripturae linguaeque Phoeniciae. Monumenta quotquot supersunt (in Latin). Vol. Pars prima. Leipzig: Fr. Chr. Guil. Vogelius. p. 95. At Google Books.

- ^ Markoe, Glenn (2000). Phoenicians. Peoples of the Past. University of California Press. p. 135. ISBN 0520226135. At Google Books.

- ^ Markoe, Glenn (2000). Phoenicians. Peoples of the Past. University of California Press. p. 167. ISBN 0520226135. At Google Books.

- ^ a b "The Illustrated Catalogue of the Industry of All Nations". The Art Journal. 2. Virtue: 224. 1853. At Google Books.

- ^ Ring, Trudy; Salkin, Robert M.; La Boda, Sharon (1995). Southern Europe. International Dictionary of Historic Places. Vol. III. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 413. ISBN 1884964052. At Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e Sznycer, Maurice (1975). "Antiquités et épigraphie nord-sémitiques". École Pratique des Hautes études 4e Section: Sciences Historiques et Philologiques. Annuaire 1974–1975 (in French). 107 (1): 191–208. At Persée.

- ^ Amadasi Guzzo, Maria Giulia (2006). Borbone, Giorgio; Mengozzi, Alessandro; Tosco, Mauro (eds.). Loquentes linguis. Linguistic and oriental studies in honour of Fabrizio A. Pennacchietti (in Italian). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 15. ISBN 3447054840. At Google Books.

- ^ Böckh, A. (1853). Corpus Inscriptionum Graecarum, 681, 5753. Vol. III. Berlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Borġ, V. (1963). Tradizioni e documenti storici. Missione. pp. 41–51.

- ^ (in Greek and Latin) Claudius Ptolemy (1843). "Book IV, Chapter 3 §37 [sic, recte §47]". In Nobbe, Carolus Fridericus Augustus (ed.). Claudii Ptolemaei Geographia (in Greek and Latin). Vol. I. Carolus Tauchnitius. p. 246. At Google Books.

- ^ Abela, Giovanni Francesco (1647). Della Descrizione di Malta Isola nel Mare Siciliano con le sue Antichità, ed Altre Notizie (in Italian). Paolo Bonacota. p. 5.

- ^ a b Prag, Jonathan R. W.; Quinn, Josephine Crawley, eds. (2013). The Hellenistic West: rethinking the ancient Mediterranean. Cambridge University Press. pp. 357–8. ISBN 978-1-107-03242-2. Brown, John Pairman, ed. (1995). Israel and Hellas. Vol. I. Walter de Gruyter. p. 120. ISBN 3-11-014233-3. At Google Books.

- ^ a b c d e Bulifon, Antonio (1698). Lettere memorabili, istoriche, politiche, ed erudite Scritte, […] Raccolta Quarta (IV). Naples: Bulifon. pp. 117–132. Also at [1]

- ^ Grima, Noel (2 May 2016). The historical antecedents of the Marsa Power Station. The Malta Independent. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ Ciantar, G.A. Dissertazione. Malta: NLM Biblioteca. pp. Ms 166, ff. 25–26r.

- ^ Ciantar, G.A.; Abela, G.F. (1772). Malta illustrata... accresciuta dal Cte G.A. Ciantar. Malta: Mallia. pp. 460–462.

- ^ a b c Paternò, Principe di Biscari, Ignazio (1781). Viaggio per tutte le antichita della Sicilia (in Italian). Napoli: Simoni. pp. 111–112. At Google Books.

- ^ Marne, Guyot (1735). Dissertazione II del Commendatore F. Giuseppe Claudio Guyot de Marne […] sopra un'inscrizione punica, e greca: Saggi di dissertazioni accademiche pubblicamente lette nella nobile accademia etrusca dell'antichissima città di Cortona. Rome: Tommaso / Pagliarini. pp. 24–34.

- ^ Fourmont, Michele (1741). Dissertazione III […] Sopra una Iscrizione Fenicia trovata a Malta, in: Saggi di dissertazioni accademiche pubblicamente lette nella nobile accademia etrusca dell'antichissima città di Cortona. Rome: Tommaso / Pagliarini. pp. 88–110.

- ^ a b Barthélemy, Jean-Jacques, Abbé (1764) [1758]. "Réflexions sur quelques monuments Phéniciens, et sur les alphabets qui en résultent". Mémoires de littérature, tirés des registres de l'Académie royale des inscriptions et belles-lettres. 30. Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres: 405–427, pl. i–iv.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) At Gallica. - ^ Bellermann, Johann Joachim (1809). Phoeniciæ linguæ vestigiorum in Melitensi specimen. Berlin: Dieterici.

- ^ Pérez Bayer, F. (1772). Del alfabeto y lengua de los Fenices, y de sus colonias (in Spanish). Spain: Joachin Ibarra. At Google Books.

- ^ "Treasures of Malta". Fondazzjoni Patrimonju Malti [Maltese Heritage Foundation]. 2009. Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ Rix, Juliet (2010). Malta and Gozo. Bradt. p. 123. ISBN 978-1841623122. At Google Books.

- ^ "Heritage Malta joins in with Lejliet Lapsi Notte Gozitana". Gozo News. 13 May 2010. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ "MaltaPost Philately". MaltaPost. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ^ "Malta- Libya 'non-paper' on illegal immigration". Times of Malta. 29 June 2005. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ^ "Pillars used to decipher Phoenician language reunited after 240-years". Times of Malta. 2023-06-02. Retrieved 2024-03-09.

Bibliography

- Culican, William (1980). Ebied, Rifaat Y.; Young, M.J.L (eds.). Oriental Studies. Leeds University Oriental Society - Near Eastern Researches II. Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-05966-0.

- Lewis, Harrison Adolphus (1977). Ancient Malta - A Study of its Antiquities. Gerrards Cross, Buckinghamshire: Colin Smythe.

- Sagona, Claudia; Vella Gregory, Isabelle; Bugeja, Anton (2006). Punic Antiquities of Malta and Other Ancient Artefacts Held in Ecclesiastic and Private Collections. Ancient Near Eastern Studies. Belgium: Peeters Publishers.

See also[edit]

- Votive Stones of Pesaro, ancient cippi

- Lucus Pisaurensis, sacred grove of Pesaro

- Encryption

- Linear A, one of two currently undeciphered writing systems used in ancient Crete

- Transliteration of Ancient Egyptian

- Greek–Punic Wars

External links[edit]

- 2nd-century BC steles

- 1694 archaeological discoveries

- Greek inscriptions

- KAI inscriptions

- Marble sculptures in France

- Archaeological discoveries in Malta

- Near Eastern and Middle Eastern antiquities in the Louvre

- Multilingual texts

- Phoenician inscriptions

- Votive offering

- Phoenician steles

- Archaeological artifacts

- Melqart