Croatia

Republic of Croatia | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: "Lijepa naša domovino" ("Our Beautiful Homeland") | |

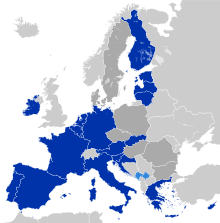

Location of Croatia (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Zagreb 45°48′47″N 15°58′39″E / 45.81306°N 15.97750°E |

| Official languages | Croatian[b] |

| Writing system | Latin[c] |

| Ethnic groups (2021) | |

| Religion (2021) |

|

| Demonym(s) | |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Zoran Milanović | |

| Andrej Plenković | |

| Legislature | Sabor |

| Establishment history | |

• Duchy | 7th century |

• Kingdom | 925 |

| 1102 | |

• Joined Habsburg Monarchy | 1 January 1527 |

• Secession from Austria-Hungary | 29 October 1918 |

| 4 December 1918 | |

| 25 June 1991[5] | |

| 22 May 1992 | |

| 12 November 1995 | |

| 1 April 2009 | |

• Joined the European Union | 1 July 2013 |

| Area | |

• Total | 56,594 km2 (21,851 sq mi) (124th) |

• Water (%) | 1.09 |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | |

• 2021 census | |

• Density | 68.4/km2 (177.2/sq mi) (152nd) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2020) | low |

| HDI (2022) | very high (39th) |

| Currency | Euro (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Date format | dd. mm. yyyy. (CE) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +385 |

| ISO 3166 code | HR |

| Internet TLD | |

Croatia (/kroʊˈeɪʃə/ ⓘ, kroh-AY-shə; Croatian: Hrvatska, pronounced [xř̩ʋaːtskaː]), officially the Republic of Croatia (Croatian: Republika Hrvatska ⓘ),[d] is a country located at the crossroads of Central and Southeast Europe. Its coast lies entirely on the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro to the southeast, and shares a maritime border with Italy to the west. Its capital and largest city, Zagreb, forms one of the country's primary subdivisions, with twenty counties. Other major urban centers include Split, Rijeka and Osijek. The country spans 56,594 square kilometres (21,851 square miles), and has a population of nearly 3.9 million.

The Croats arrived in modern-day Croatia in the late 6th century, then part of Roman Illyria. By the 7th century, they had organized the territory into two duchies. Croatia was first internationally recognized as independent on 7 June 879 during the reign of Duke Branimir. Tomislav became the first king by 925, elevating Croatia to the status of a kingdom. During the succession crisis after the Trpimirović dynasty ended, Croatia entered a personal union with Hungary in 1102. In 1527, faced with Ottoman conquest, the Croatian Parliament elected Ferdinand I of Austria to the Croatian throne. In October 1918, the State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs, independent from Austria-Hungary, was proclaimed in Zagreb, and in December 1918, it merged into the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Following the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, most of Croatia was incorporated into a Nazi-installed puppet state, the Independent State of Croatia. A resistance movement led to the creation of the Socialist Republic of Croatia, which after the war became a founding member and constituent of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. On 25 June 1991, Croatia declared independence, and the War of Independence was successfully fought over the next four years.

Croatia is a republic and a parliamentary liberal democracy. It is a member of the European Union, the Eurozone, the Schengen Area, NATO, the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the OSCE, the World Trade Organization, a founding member of the Union for the Mediterranean, and is currently in the process of joining the OECD. An active participant in United Nations peacekeeping, Croatia contributed troops to the International Security Assistance Force and was elected to fill a non-permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council in the 2008–2009 term for the first time.

Croatia is a developed country with an advanced high-income economy and ranks highly in the Human Development Index.[12] Service, industrial sectors, and agriculture dominate the economy. Tourism is a significant source of revenue for the country with nearly 20 million tourist arrivals as of 2019.[13][14][15] Since 2000s, the Croatian government has heavily invested in infrastructure, especially transport routes and facilities along the Pan-European corridors. Croatia has also positioned itself as a regional energy leader in the early 2020s and is contributing to the diversification of Europe's energy supply via its floating liquefied natural gas import terminal off Krk island, LNG Hrvatska.[16] Croatia provides social security, universal health care, and tuition-free primary and secondary education while supporting culture through public institutions and corporate investments in media and publishing.

Etymology

Croatia's non-native name derives from Medieval Latin Croātia, itself a derivation of North-West Slavic *Xərwate, by liquid metathesis from Common Slavic period *Xorvat, from proposed Proto-Slavic *Xъrvátъ which possibly comes from the 3rd-century Scytho-Sarmatian form attested in the Tanais Tablets as Χοροάθος (Khoroáthos, alternate forms comprise Khoróatos and Khoroúathos).[17] The origin of the ethnonym is uncertain, but most probably is from Proto-Ossetian / Alanian *xurvæt- or *xurvāt-, in the meaning of "one who guards" ("guardian, protector").[18]

The oldest preserved record of the Croatian ethnonym's native variation *xъrvatъ is of the variable stem, attested in the Baška tablet in style zvъnъmirъ kralъ xrъvatъskъ ("Zvonimir, Croatian king"),[19] while the Latin variation Croatorum is archaeologically confirmed on a church inscription found in Bijaći near Trogir dated to the end of the 8th or early 9th century.[20] The presumably oldest stone inscription with fully preserved ethnonym is the 9th-century Branimir inscription found near Benkovac, where Duke Branimir is styled Dux Cruatorvm, likely dated between 879 and 892, during his rule.[21] The Latin term Chroatorum is attributed to a charter of Duke Trpimir I of Croatia, dated to 852 in a 1568 copy of a lost original, but it is not certain if the original was indeed older than the Branimir inscription.[22][23]

History

Prehistory

Right: Croatian Apoxyomenos, Ancient Greek statue, 2nd or 1st century BC.

The area known as Croatia today was inhabited throughout the prehistoric period. Neanderthal fossils dating to the middle Palaeolithic period were unearthed in northern Croatia, best presented at the Krapina site.[24] Remnants of Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultures were found in all regions.[25] The largest proportion of sites is in the valleys of northern Croatia. The most significant are Baden, Starčevo, and Vučedol cultures.[26][27] Iron Age hosted the early Illyrian Hallstatt culture and the Celtic La Tène culture.[28]

Antiquity

The region of modern-day Croatia was settled by Illyrians and Liburnians, while the first Greek colonies were established on the islands of Hvar,[29] Korčula, and Vis.[30] In 9 AD, the territory of today's Croatia became part of the Roman Empire. Emperor Diocletian was native to the region. He had a large palace built in Split, to which he retired after abdicating in AD 305.[31]

Middle Ages

During the 5th century, the last de jure Western Roman Emperor Julius Nepos ruled a small realm from the palace after fleeing Italy in 475.[32] The period ends with Avar and Croat invasions in the late 6th and first half of the 7th century and the destruction of almost all Roman towns. Roman survivors retreated to more favourable sites on the coast, islands, and mountains. The city of Dubrovnik was founded by such survivors from Epidaurum.[33]

The ethnogenesis of Croats is uncertain. The most accepted theory, the Slavic theory, proposes migration of White Croats from White Croatia during the Migration Period. Conversely, the Iranian theory proposes Iranian origin, based on Tanais Tablets containing Ancient Greek inscriptions of given names Χορούαθος, Χοροάθος, and Χορόαθος (Khoroúathos, Khoroáthos, and Khoróathos) and their interpretation as anthroponyms of Croatian people.[34]

According to the work De Administrando Imperio written by 10th-century Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII, Croats arrived in the Roman province of Dalmatia in the first half of the 7th century after they defeated the Avars.[35][36][37] However, that claim is disputed: competing hypotheses date the event between the late 6th-early 7th (mainstream) or the late 8th-early 9th (fringe) centuries,[38][39] but recent archaeological data has established that the migration and settlement of the Slavs/Croats was in the late 6th and early 7th century.[40][41][42] Eventually, a dukedom was formed, Duchy of Croatia, ruled by Borna, as attested by chronicles of Einhard starting in 818. The record represents the first document of Croatian realms, vassal states of Francia at the time.[43] Its neighbor to the North was Principality of Lower Pannonia, at the time ruled by duke Ljudevit who ruled the territories between the Drava and Sava rivers, centred from his fort at Sisak. This population and territory throughout history was tightly related and connected to Croats and Croatia.[44]

Christianisation of Croats began in the 7th century at the time of archon Porga of Croatia, initially probably encompassed only the elite and related people,[45] but mostly finished by the 9th century.[46][47] The Frankish overlordship ended during the reign of Mislav,[48] or his successor Trpimir I.[49] The native Croatian royal dynasty was founded by duke Trpimir I in the mid 9th century, who defeated the Byzantine and Bulgarian forces.[50] The first native Croatian ruler recognised by the Pope was duke Branimir, who received papal recognition from Pope John VIII on 7 June 879.[21] Tomislav was the first king of Croatia, noted as such in a letter of Pope John X in 925. Tomislav defeated Hungarian and Bulgarian invasions.[51] The medieval Croatian kingdom reached its peak in the 11th century during the reigns of Petar Krešimir IV (1058–1074) and Dmitar Zvonimir (1075–1089).[52] When Stjepan II died in 1091, ending the Trpimirović dynasty, Dmitar Zvonimir's brother-in-law Ladislaus I of Hungary claimed the Croatian crown. This led to a war and personal union with Hungary in 1102 under Coloman.[53]

Personal union with Hungary (1102) and Habsburg Monarchy (1527)

For the next four centuries, the Kingdom of Croatia was ruled by the Sabor (parliament) and a Ban (viceroy) appointed by the king.[54] This period saw the rise of influential nobility such as the Frankopan and Šubić families to prominence, and ultimately numerous Bans from the two families.[55] An increasing threat of Ottoman conquest and a struggle against the Republic of Venice for control of coastal areas ensued. The Venetians controlled most of Dalmatia by 1428, except the city-state of Dubrovnik, which became independent. Ottoman conquests led to the 1493 Battle of Krbava field and the 1526 Battle of Mohács, both ending in decisive Ottoman victories. King Louis II died at Mohács, and in 1527, the Croatian Parliament met in Cetin and chose Ferdinand I of the House of Habsburg as the new ruler of Croatia, under the condition that he protects Croatia against the Ottoman Empire while respecting its political rights.[54][56]

Following the decisive Ottoman victories, Croatia was split into civilian and military territories in 1538. The military territories became known as the Croatian Military Frontier and were under direct Habsburg control. Ottoman advances in Croatia continued until the 1593 Battle of Sisak, the first decisive Ottoman defeat, when borders stabilised.[56] During the Great Turkish War (1683–1698), Slavonia was regained, but western Bosnia, which had been part of Croatia before the Ottoman conquest, remained outside Croatian control.[56] The present-day border between the two countries is a remnant of this outcome. Dalmatia, the southern part of the border, was similarly defined by the Fifth and the Seventh Ottoman–Venetian Wars.[57]

The Ottoman wars drove demographic changes. During the 16th century, Croats from western and northern Bosnia, Lika, Krbava, the area between the rivers of Una and Kupa, and especially from western Slavonia, migrated towards Austria. Present-day Burgenland Croats are direct descendants of these settlers.[58][59] To replace the fleeing population, the Habsburgs encouraged Bosnians to provide military service in the Military Frontier.

The Croatian Parliament supported King Charles III's Pragmatic Sanction and signed their own Pragmatic Sanction in 1712.[60] Subsequently, the emperor pledged to respect all privileges and political rights of the Kingdom of Croatia, and Queen Maria Theresa made significant contributions to Croatian affairs, such as introducing compulsory education.

Between 1797 and 1809, the First French Empire increasingly occupied the eastern Adriatic coastline and its hinterland, ending the Venetian and the Ragusan republics, establishing the Illyrian Provinces.[56] In response, the Royal Navy blockaded the Adriatic Sea, leading to the Battle of Vis in 1811.[61] The Illyrian provinces were captured by the Austrians in 1813 and absorbed by the Austrian Empire following the Congress of Vienna in 1815. This led to the formation of the Kingdom of Dalmatia and the restoration of the Croatian Littoral to the Kingdom of Croatia under one crown.[62] The 1830s and 1840s featured romantic nationalism that inspired the Croatian National Revival, a political and cultural campaign advocating the unity of South Slavs within the empire. Its primary focus was establishing a standard language as a counterweight to Hungarian while promoting Croatian literature and culture.[63] During the Hungarian Revolution of 1848, Croatia sided with Austria. Ban Josip Jelačić helped defeat the Hungarians in 1849 and ushered in a Germanisation policy.[64]

By the 1860s, the failure of the policy became apparent, leading to the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. The creation of a personal union between the Austrian Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary followed. The treaty left Croatia's status to Hungary, which was resolved by the Croatian–Hungarian Settlement of 1868 when the kingdoms of Croatia and Slavonia were united.[65] The Kingdom of Dalmatia remained under de facto Austrian control, while Rijeka retained the status of corpus separatum introduced in 1779.[53]

After Austria-Hungary occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina following the 1878 Treaty of Berlin, the Military Frontier was abolished. The Croatian and Slavonian sectors of the Frontier returned to Croatia in 1881,[56] under provisions of the Croatian–Hungarian Settlement.[66][67] Renewed efforts to reform Austria-Hungary, entailing federalisation with Croatia as a federal unit, were stopped by World War I.[68]

First Yugoslavia (1918–1941)

On 29 October 1918 the Croatian Parliament (Sabor) declared independence and decided to join the newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs,[54] which in turn entered into union with the Kingdom of Serbia on 4 December 1918 to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes.[69] The Croatian Parliament never ratified the union with Serbia and Montenegro.[54] The 1921 constitution defining the country as a unitary state and abolition of Croatian Parliament and historical administrative divisions effectively ended Croatian autonomy.

The new constitution was opposed by the most widely supported national political party—the Croatian Peasant Party (HSS) led by Stjepan Radić.[70]

The political situation deteriorated further as Radić was assassinated in the National Assembly in 1928, culminating in King Alexander I's establishment of the 6 January Dictatorship in 1929.[71] The dictatorship formally ended in 1931 when the king imposed a more unitary constitution.[72] The HSS, now led by Vladko Maček, continued to advocate federalisation, resulting in the Cvetković–Maček Agreement of August 1939 and the autonomous Banovina of Croatia. The Yugoslav government retained control of defence, internal security, foreign affairs, trade, and transport while other matters were left to the Croatian Sabor and a crown-appointed Ban.[73]

World War II and Independent State of Croatia

In April 1941, Yugoslavia was occupied by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Following the invasion, a German-Italian installed puppet state named the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) was established. Most of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the region of Syrmia were incorporated into this state. Parts of Dalmatia were annexed by Italy, Hungary annexed the northern Croatian regions of Baranja and Međimurje.[74] The NDH regime was led by Ante Pavelić and ultranationalist Ustaše, a fringe movement in pre-war Croatia.[75] With German and Italian military and political support,[76] the regime introduced racial laws and launched a genocide campaign against Serbs, Jews, and Roma.[77] Many were imprisoned in concentration camps; the largest was the Jasenovac complex.[78] Anti-fascist Croats were targeted by the regime as well.[79] Several concentration camps (most notably the Rab, Gonars and Molat camps) were established in Italian-occupied territories, mostly for Slovenes and Croats.[78] At the same time, the Yugoslav Royalist and Serbian nationalist Chetniks pursued a genocidal campaign against Croats and Muslims,[77][80] aided by Italy.[81] Nazi German forces committed crimes and reprisals against civilians in retaliation for Partisan actions, such as in the villages of Kamešnica and Lipa in 1944.[82][83]

A resistance movement emerged. On 22 June 1941,[84] the 1st Sisak Partisan Detachment was formed near Sisak, the first military unit formed by a resistance movement in occupied Europe.[85] That sparked the beginning of the Yugoslav Partisan movement, a communist, multi-ethnic anti-fascist resistance group led by Josip Broz Tito.[86] In ethnic terms, Croats were the second-largest contributors to the Partisan movement after Serbs.[87] In per capita terms, Croats contributed proportionately to their population within Yugoslavia.[88] By May 1944 (according to Tito), Croats made up 30% of the Partisan's ethnic composition, despite making up 22% of the population.[87] The movement grew fast, and at the Tehran Conference in December 1943, the Partisans gained recognition from the Allies.[89]

With Allied support in logistics, equipment, training and airpower, and with the assistance of Soviet troops taking part in the 1944 Belgrade Offensive, the Partisans gained control of Yugoslavia and the border regions of Italy and Austria by May 1945. Members of the NDH armed forces and other Axis troops, as well as civilians, were in retreat towards Austria. Following their surrender, many were killed in the Yugoslav death march of Nazi collaborators.[90] In the following years, ethnic Germans faced persecution in Yugoslavia, and many were interned.[91]

The political aspirations of the Partisan movement were reflected in the State Anti-fascist Council for the National Liberation of Croatia, which developed in 1943 as the bearer of Croatian statehood and later transformed into the Parliament in 1945, and AVNOJ—its counterpart at the Yugoslav level.[92][93]

Based on the studies on wartime and post-war casualties by demographer Vladimir Žerjavić and statistician Bogoljub Kočović, a total of 295,000 people from the territory (not including territories ceded from Italy after the war) died, which amounted to 7.3% of the population,[94] among whom were 125–137,000 Serbs, 118–124,000 Croats, 16–17,000 Jews, and 15,000 Roma.[95][96] In addition, from areas joined to Croatia after the war, a total of 32,000 people died, among whom 16,000 were Italians and 15,000 were Croats.[97] Approximately 200,000 Croats from the entirety of Yugoslavia (including Croatia) and abroad were killed in total throughout the war and its immediate aftermath, approximately 5.4% of the population.[98][99]

Second Yugoslavia (1945–1991)

After World War II, Croatia became a single-party socialist federal unit of the SFR Yugoslavia, ruled by the Communists, but having a degree of autonomy within the federation. In 1967, Croatian authors and linguists published a Declaration on the Status and Name of the Croatian Standard Language demanding equal treatment for their language.[100]

The declaration contributed to a national movement seeking greater civil rights and redistribution of the Yugoslav economy, culminating in the Croatian Spring of 1971, which was suppressed by Yugoslav leadership.[101] Still, the 1974 Yugoslav Constitution gave increased autonomy to federal units, basically fulfilling a goal of the Croatian Spring and providing a legal basis for independence of the federative constituents.[102]

Following Tito's death in 1980, the political situation in Yugoslavia deteriorated. National tension was fanned by the 1986 SANU Memorandum and the 1989 coups in Vojvodina, Kosovo, and Montenegro.[103][104] In January 1990, the Communist Party fragmented along national lines, with the Croatian faction demanding a looser federation.[105] In the same year, the first multi-party elections were held in Croatia, while Franjo Tuđman's win exacerbated nationalist tensions.[106] Some of the Serbs in Croatia left Sabor and declared autonomy of the unrecognised Republic of Serbian Krajina, intent on achieving independence from Croatia.[107][108]

Croatian War of Independence

As tensions rose, Croatia declared independence on 25 June 1991. However, the full implementation of the declaration only came into effect after a three-month moratorium on the decision on 8 October 1991.[109][110] In the meantime, tensions escalated into overt war when the Serbian-controlled Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) and various Serb paramilitary groups attacked Croatia.[111]

By the end of 1991, a high-intensity conflict fought along a wide front reduced Croatia's control to about two-thirds of its territory.[112][113] Serb paramilitary groups then began a campaign of killing, terror, and expulsion of the Croats in the rebel territories, killing thousands[114] of Croat civilians and expelling or displacing as many as 400,000 Croats and other non-Serbs from their homes.[115] Serbs living in Croatian towns, especially those near the front lines, were subjected to various forms of discrimination.[116] Croatian Serbs in Eastern and Western Slavonia and parts of the Krajina were forced to flee or were expelled by Croatian forces, though on a restricted scale and in lesser numbers.[117] The Croatian Government publicly deplored these practices and sought to stop them, indicating that they were not a part of the Government's policy. [118]

On 15 January 1992, Croatia gained diplomatic recognition by the European Economic Community, followed by the United Nations.[119][120] The war effectively ended in August 1995 with a decisive victory by Croatia;[121] the event is commemorated each year on 5 August as Victory and Homeland Thanksgiving Day and the Day of Croatian Defenders.[122] Following the Croatian victory, about 200,000 Serbs from the self-proclaimed Republic of Serbian Krajina fled the region[123] and hundreds of mainly elderly Serb civilians were killed in the aftermath of the military operation.[124] Their lands were subsequently settled by Croat refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina.[125] The remaining occupied areas were restored to Croatia following the Erdut Agreement of November 1995, concluding with the UNTAES mission in January 1998.[126] Most sources number the war deaths at around 20,000.[127][128][129]

Independent Croatia (1991–present)

After the end of the war, Croatia faced the challenges of post-war reconstruction, the return of refugees, establishing democracy, protecting human rights, and general social and economic development.

The 2000s period is characterized by democratization, economic growth, structural and social reforms, and problems such as unemployment, corruption, and the inefficiency of public administration.[130] In November 2000 and March 2001, the Parliament amended the Constitution, first adopted on 22 December 1990, changing its bicameral structure back into its historic unicameral form and reducing presidential powers.[131][132]

Croatia joined the Partnership for Peace on 25 May 2000[133] and became a member of the World Trade Organization on 30 November 2000.[134] On 29 October 2001, Croatia signed a Stabilisation and Association Agreement with the European Union,[135] submitted a formal application for the EU membership in 2003,[136] was given the status of a candidate country in 2004,[137] and began accession negotiations in 2005.[138] Although the Croatian economy had enjoyed a significant boom in the early 2000s, the financial crisis in 2008 forced the government to cut spending, thus provoking a public outcry.[139]

Croatia served on the United Nations Security Council in the 2008–2009 term for the first time, assuming the non-permanent seat in December 2008.[140] On 1 April 2009, Croatia joined NATO.[141]

A wave of anti-government protests in 2011 reflected a general dissatisfaction with the current political and economic situation. The protests brought together diverse political persuasions in response to recent government corruption scandals and called for early elections. On 28 October 2011 MPs voted to dissolve Parliament and the protests gradually subsided. President Ivo Josipović agreed to a dissolution of Sabor on Monday, 31 October and scheduled new elections for Sunday 4 December 2011.[142][143][144]

On 30 June 2011, Croatia successfully completed EU accession negotiations.[145] The country signed the Accession Treaty on 9 December 2011 and held a referendum on 22 January 2012, where Croatian citizens voted in favor of an EU membership.[146][147] Croatia joined the European Union on 1 July 2013.

Croatia was affected by the 2015 European migrant crisis when Hungary's closure of borders with Serbia pushed over 700,000 refugees and migrants to pass through Croatia on their way to other EU countries.[148]

On 25 January 2022, the OECD Council decided to open accession negotiations with Croatia. Throughout the accession process, Croatia is to implement numerous reforms that will advance all spheres of activity – from public services and the justice system to education, transport, finance, health, and trade. In line with the OECD Accession Roadmap from June 2022, Croatia will undergo technical reviews by 25 OECD committees and is so far progressing at a faster pace than expected. Full membership is expected in 2025 and is the last big foreign policy goal Croatia still has to achieve.[149][150][151][152]

On 19 October 2016, Andrej Plenković began serving as the current Croatian Prime Minister.[153] The most recent presidential elections, held on 5 January 2020, elected Zoran Milanović as president.[154]

On 1 January 2023 Croatia adopted the euro as its official currency, replacing the kuna, and became the 20th Eurozone member. On the same day, Croatia became the 27th member of the border-free Schengen Area, thus marking its full EU integration.[155]

Geography

Croatia is situated in Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. Hungary is to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro to the southeast and Slovenia to the northwest.[citation needed] It lies mostly between latitudes 42° and 47° N and longitudes 13° and 20° E.[156] Part of the territory in the extreme south surrounding Dubrovnik is a practical exclave connected to the rest of the mainland by territorial waters, but separated on land by a short coastline strip belonging to Bosnia and Herzegovina around Neum. The Pelješac Bridge connects the exclave with mainland Croatia.[citation needed]

The territory covers 56,594 square kilometres (21,851 square miles), consisting of 56,414 square kilometres (21,782 square miles) of land and 128 square kilometres (49 square miles) of water. It is the world's 127th largest country.[157] Elevation ranges from the mountains of the Dinaric Alps with the highest point of the Dinara peak at 1,831 metres (6,007 feet) near the border with Bosnia and Herzegovina in the south[157] to the shore of the Adriatic Sea which makes up its entire southwest border. Insular Croatia consists of over a thousand islands and islets varying in size, 48 of which permanently inhabited. The largest islands are Cres and Krk,[157] each of them having an area of around 405 square kilometres (156 square miles).

The hilly northern parts of Hrvatsko Zagorje and the flat plains of Slavonia in the east which is part of the Pannonian Basin are traversed by major rivers such as Danube, Drava, Kupa, and the Sava. The Danube, Europe's second longest river, runs through the city of Vukovar in the extreme east and forms part of the border with Vojvodina. The central and southern regions near the Adriatic coastline and islands consist of low mountains and forested highlands. Natural resources found in quantities significant enough for production include oil, coal, bauxite, low-grade iron ore, calcium, gypsum, natural asphalt, silica, mica, clays, salt, and hydropower.[157] Karst topography makes up about half of Croatia and is especially prominent in the Dinaric Alps.[158] Croatia hosts deep caves, 49 of which are deeper than 250 m (820.21 ft), 14 deeper than 500 m (1,640.42 ft) and three deeper than 1,000 m (3,280.84 ft). Croatia's most famous lakes are the Plitvice lakes, a system of 16 lakes with waterfalls connecting them over dolomite and limestone cascades. The lakes are renowned for their distinctive colours, ranging from turquoise to mint green, grey or blue.[159]

Climate

Most of Croatia has a moderately warm and rainy continental climate as defined by the Köppen climate classification. Mean monthly temperature ranges between −3 °C (27 °F) in January and 18 °C (64 °F) in July. The coldest parts of the country are Lika and Gorski Kotar featuring a snowy, forested climate at elevations above 1,200 metres (3,900 feet). The warmest areas are at the Adriatic coast and especially in its immediate hinterland characterised by Mediterranean climate, as the sea moderates temperature highs. Consequently, temperature peaks are more pronounced in continental areas.

The lowest temperature of −35.5 °C (−31.9 °F) was recorded on 3 February 1919 in Čakovec,[160] and the highest temperature of 42.8 °C (109.0 °F) was recorded on 4 August 1981 in Ploče.[161]

Mean annual precipitation ranges between 600 millimetres (24 inches) and 3,500 millimetres (140 inches) depending on geographic region and climate type. The least precipitation is recorded in the outer islands (Biševo, Lastovo, Svetac, Vis) and the eastern parts of Slavonia. However, in the latter case, rain occurs mostly during the growing season. The maximum precipitation levels are observed in the Dinaric Alps, in the Gorski Kotar peaks of Risnjak and Snježnik.[160]

Prevailing winds in the interior are light to moderate northeast or southwest, and in the coastal area, prevailing winds are determined by local features. Higher wind velocities are more often recorded in cooler months along the coast, generally as the cool northeasterly bura or less frequently as the warm southerly jugo. The sunniest parts are the outer islands, Hvar and Korčula, where more than 2700 hours of sunshine are recorded per year, followed by the middle and southern Adriatic Sea area in general, and northern Adriatic coast, all with more than 2000 hours of sunshine per year.[162]

Biodiversity

Croatia can be subdivided into ecoregions based on climate and geomorphology. The country is one of the richest in Europe in terms of biodiversity.[163][164] Croatia has four types of biogeographical regions—the Mediterranean along the coast and in its immediate hinterland, Alpine in most of Lika and Gorski Kotar, Pannonian along Drava and Danube, and Continental in the remaining areas. The most significant are karst habitats which include submerged karst, such as Zrmanja and Krka canyons and tufa barriers, as well as underground habitats. The country contains three ecoregions: Dinaric Mountains mixed forests, Pannonian mixed forests, and Illyrian deciduous forests.[165]

The karst geology harbours approximately 7,000 caves and pits, some of which are the habitat of the only known aquatic cave vertebrate—the olm. Forests are significantly present, as they cover 2,490,000 hectares (6,200,000 acres) representing 44% of Croatian land area. Other habitat types include wetlands, grasslands, bogs, fens, scrub habitats, coastal and marine habitats.[166]

In terms of phytogeography, Croatia is a part of the Boreal Kingdom and is a part of Illyrian and Central European provinces of the Circumboreal Region and the Adriatic province of the Mediterranean Region. The World Wide Fund for Nature divides Croatia between three ecoregions—Pannonian mixed forests, Dinaric Mountains mixed forests and Illyrian deciduous forests.[167]

Croatia hosts 37,000 known plant and animal species, but their actual number is estimated to be between 50,000 and 100,000.[166] More than a thousand species are endemic, especially in Velebit and Biokovo mountains, Adriatic islands and karst rivers. Legislation protects 1,131 species.[166] The most serious threat is habitat loss and degradation. A further problem is presented by invasive alien species, especially Caulerpa taxifolia algae. Croatia had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.92/10, ranking it 113th of 172 countries.[168]

Invasive algae are regularly monitored and removed to protect benthic habitat. Indigenous cultivated plant strains and domesticated animal breeds are numerous. They include five breeds of horses, five of cattle, eight of sheep, two of pigs, and one poultry. Indigenous breeds include nine that are endangered or critically endangered.[166] Croatia has 444 protected areas, encompassing 9% of the country. Those include eight national parks, two strict reserves, and ten nature parks. The most famous protected area and the oldest national park in Croatia is Plitvice Lakes National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Velebit Nature Park is a part of the UNESCO Man and the Biosphere Programme. The strict and special reserves, as well as the national and nature parks, are managed and protected by the central government, while other protected areas are managed by counties. In 2005, the National Ecological Network was set up, as the first step in the preparation of the EU accession and joining of the Natura 2000 network.[166]

Governance

The Republic of Croatia is a unitary, constitutional state using a parliamentary system. Government powers in Croatia are legislative, executive, and judiciary powers.[169] The president of the republic (Croatian: Predsjednik Republike) is the head of state, directly elected to a five-year term and is limited by the Constitution to two terms. In addition to serving as commander in chief of the armed forces, the president has the procedural duty of appointing the prime minister with the parliament and has some influence on foreign policy.[169]

The Government is headed by the prime minister, who has four deputy prime ministers and 16 ministers in charge of particular sectors.[170] As the executive branch, it is responsible for proposing legislation and a budget, enforcing the laws, and guiding foreign and internal policies. The Government is seated at Banski dvori in Zagreb.[169]

Law and judicial system

A unicameral parliament (Sabor) holds legislative power. The number of Sabor members can vary from 100 to 160. They are elected by popular vote to serve four-year terms. Legislative sessions take place from 15 January to 15 July, and from 15 September to 15 December annually.[171] The two largest political parties in Croatia are the Croatian Democratic Union and the Social Democratic Party of Croatia.[172]

Croatia has a civil law legal system in which law arises primarily from written statutes, with judges serving as implementers and not creators of law. Its development was largely influenced by German and Austrian legal systems. Croatian law is divided into two principal areas—private and public law. Before EU accession negotiations were completed, Croatian legislation had been fully harmonised with the Community acquis.[173]

The main national courts are the Constitutional Court, which oversees violations of the Constitution, and the Supreme Court, which is the highest court of appeal. Administrative, Commercial, County, Misdemeanor, and Municipal courts handle cases in their respective domains.[174] Cases falling within judicial jurisdiction are in the first instance decided by a single professional judge, while appeals are deliberated in mixed tribunals of professional judges. Lay magistrates also participate in trials.[175] The State's Attorney Office is the judicial body constituted of public prosecutors empowered to instigate prosecution of perpetrators of offences.[176]

Law enforcement agencies are organised under the authority of the Ministry of the Interior which consist primarily of the national police force. Croatia's security service is the Security and Intelligence Agency (SOA).[177][178]

Foreign relations

Croatia has established diplomatic relations with 194 countries.[179] supporting 57 embassies, 30 consulates and eight permanent diplomatic missions. 56 foreign embassies and 67 consulates operate in the country in addition to offices of international organisations such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), International Organization for Migration (IOM), Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), World Bank, World Health Organization (WHO), International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), and UNICEF.[180]

As of 2019, the Croatian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration employed 1,381[needs update] personnel and expended 765.295 million kunas (€101.17 million).[181] Stated aims of Croatian foreign policy include enhancing relations with neighbouring countries, developing international co-operation and promotion of the Croatian economy and Croatia itself.[182]

Croatia is a member of the European Union. As of 2021, Croatia had unsolved border issues with Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia, and Slovenia.[183] Croatia is a member of NATO.[184][185] On 1 January 2023, Croatia simultaneously joined both the Schengen Area and the Eurozone,[186] having previously joined the ERM II on 10 July 2020.

Croatian diaspora

The Croatian diaspora consists of communities of ethnic Croats and Croatian citizens living outside Croatia. Croatia maintains intensive contacts with Croatian communities abroad (e.g., administrative and financial support of cultural, sports activities, and economic initiatives). Croatia actively maintain foreign relations to strengthen and guarantee the rights of the Croatian minority in various host countries.[187][188][189]

Military

The Croatian Armed Forces (CAF) consist of the Air Force, Army, and Navy branches in addition to the Education and Training Command and Support Command. The CAF is headed by the General Staff, which reports to the defence minister, who in turn reports to the president. According to the constitution, the president is the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. In case of immediate threat during wartime, he issues orders directly to the General Staff.[190]

Following the 1991–95 war, defence spending and CAF size began a constant decline. As of 2019[update], military spending was an estimated 1.68% of the country's GDP, 67th globally.[191] In 2005 the budget fell below the NATO-required 2% of GDP, down from the record high of 11.1% in 1994.[192] Traditionally relying on conscripts, the CAF went through a period of reforms focused on downsizing, restructuring and professionalisation in the years before accession to NATO in April 2009. According to a presidential decree issued in 2006, the CAF employed around 18,100 active duty military personnel, 3,000 civilians and 2,000 voluntary conscripts between 18 and 30 years old in peacetime.[190]

Compulsory conscription was abolished in January 2008.[157] Until 2008 military service was obligatory for men at age 18 and conscripts served six-month tours of duty, reduced in 2001 from the earlier scheme of nine months. Conscientious objectors could instead opt for eight months of civilian service.[193]

As of May 2019[update], the Croatian military had 72 members stationed in foreign countries as part of United Nations-led international peacekeeping forces.[194] As of 2019[update], 323 troops served the NATO-led ISAF force in Afghanistan. Another 156 served with KFOR in Kosovo.[195][196]

Croatia has a military-industrial sector that exported around 493 million kunas (€65,176 million) worth of military equipment in 2020.[197] Croatian-made weapons and vehicles used by CAF include the standard sidearm HS2000 manufactured by HS Produkt and the M-84D battle tank designed by the Đuro Đaković factory. Uniforms and helmets worn by CAF soldiers are locally produced and marketed to other countries.[198]

Administrative divisions

Croatia was first divided into counties in the Middle Ages.[199] The divisions changed over time to reflect losses of territory to Ottoman conquest and subsequent liberation of the same territory, changes of the political status of Dalmatia, Dubrovnik, and Istria. The traditional division of the country into counties was abolished in the 1920s when the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and the subsequent Kingdom of Yugoslavia introduced oblasts and banovinas respectively.[200]

Communist-ruled Croatia, as a constituent part of post-World War II Yugoslavia, abolished earlier divisions and introduced municipalities, subdividing Croatia into approximately one hundred municipalities. Counties were reintroduced in 1992 legislation, significantly altered in terms of territory relative to the pre-1920s subdivisions. In 1918, the Transleithanian part was divided into eight counties with their seats in Bjelovar, Gospić, Ogulin, Osijek, Požega, Varaždin, Vukovar, and Zagreb.[201][202]

As of 1992, Croatia is divided into 20 counties and the capital city of Zagreb, the latter having the dual authority and legal status of a county and a city. County borders changed in some instances, last revised in 2006. The counties subdivide into 127 cities and 429 municipalities.[203] Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS) division is performed in several tiers. NUTS 1 level considers the entire country in a single unit; three NUTS 2 regions come below that. Those are Northwest Croatia, Central and Eastern (Pannonian) Croatia, and Adriatic Croatia. The latter encompasses the counties along the Adriatic coast. Northwest Croatia includes Koprivnica-Križevci, Krapina-Zagorje, Međimurje, Varaždin, the city of Zagreb, and Zagreb counties and the Central and Eastern (Pannonian) Croatia includes the remaining areas—Bjelovar-Bilogora, Brod-Posavina, Karlovac, Osijek-Baranja, Požega-Slavonia, Sisak-Moslavina, Virovitica-Podravina, and Vukovar-Syrmia counties. Individual counties and the city of Zagreb also represent NUTS 3 level subdivision units in Croatia. The NUTS local administrative unit divisions are two-tiered. LAU 1 divisions match the counties and the city of Zagreb in effect making those the same as NUTS 3 units, while LAU 2 subdivisions correspond to cities and municipalities.[204]

Economy

This section needs to be updated. (June 2022) |

Croatia's economy qualifies as high-income.[205] International Monetary Fund data projected that Croatian nominal GDP reached $67,84 billion, or $17.398 per capita for 2021[206] while purchasing power parity GDP was $132,88 billion, or $32.942 per capita.[207] According to Eurostat, Croatian GDP per capita in PPS stood at 65% of the EU average in 2019.[208] Real GDP growth in 2022 was 6.2 per cent.[209] The average net salary of a Croatian worker in October 2019 was 6,496 HRK per month (roughly 873 EUR), and the average gross salary was 8,813 HRK per month (roughly 1,185 EUR).[210] As of July 2019[update], the unemployment rate dropped to 7.2% from 9.6% in December 2018. The number of unemployed persons was 106.703. The unemployment rate between 1996 and 2018 averaged 17.38%, reaching an all-time high of 23.60% in January 2002 and a record low of 8.40% in September 2018.[211] In 2017, economic output was dominated by the service sector — accounting for 70.1% of GDP — followed by the industrial sector with 26.2% and agriculture accounting for 3.7%.[212]

According to 2017 data, 1.9% of the workforce were employed in agriculture, 27.3% by industry and 70.8% in services.[212] Shipbuilding, food processing, pharmaceuticals, information technology, biochemical, and timber industry dominate the industrial sector. In 2018, Croatian exports were valued at 108 billion kunas (€14.61 billion) with 176 billion kunas (€23.82 billion) worth of imports. Croatia's largest trading partner was the rest of the European Union, led by Germany, Italy, and Slovenia.[213] According to Eurostat, Croatia has the highest quantity of water resources per capita in the EU (30,000 m3).[214]

As a result of the war, economic infrastructure sustained massive damage, particularly the tourism industry. From 1989 to 1993, the GDP fell 40.5%. The Croatian state still controls significant economic sectors, with government expenditures accounting for 40% of GDP.[215] A particular concern is a backlogged judiciary system, with inefficient public administration and corruption, upending land ownership. In the 2022 Corruption Perceptions Index, published by Transparency International, the country ranked 57th.[216] At the end of June 2020, the national debt stood at 85.3% of GDP.[217]

Tourism

Tourism dominates the Croatian service sector and accounts for up to 20% of GDP. Tourism income for 2019 was estimated to be €10.5 billion.[218] Its positive effects are felt throughout the economy, increasing retail business, and increasing seasonal employment. The industry is counted as an export business because foreign visitor spending significantly reduces the country's trade imbalance.[219] The tourist industry has rapidly grown, recording a sharp rise in tourist numbers since independence, attracting more than 17 million visitors each year (as of 2017[update]).[220] Germany, Slovenia, Austria, Italy, United Kingdom, Czechia, Poland, Hungary, France, Netherlands, Slovakia and Croatia itself provide the most visitors.[221] Tourist stays averaged 4.7 days in 2019.[222]

Much of the tourist industry is concentrated along the coast. Opatija was the first holiday resort. It first became popular in the middle of the 19th century. By the 1890s, it had become one of the largest European health resorts.[223] Resorts sprang up along the coast and islands, offering services catering to mass tourism and various niche markets. The most significant are nautical tourism, supported by marinas with more than 16 thousand berths, cultural tourism relying on the appeal of medieval coastal cities and cultural events taking place during the summer. Inland areas offer agrotourism, mountain resorts, and spas. Zagreb is a significant destination, rivalling major coastal cities and resorts.[224]

Croatia has unpolluted marine areas with nature reserves and 116 Blue Flag beaches.[225] Croatia was ranked first in Europe for swimming water quality in 2022 by European Environmental Agency.[226]

Croatia ranked as the 23rd-most popular tourist destination in the world according to the World Tourism Organization in 2019.[227] About 15% of these visitors,[which?][quantify] or over one million per year, participate in naturism, for which Croatia is famous. It was the first European country to develop commercial naturist resorts.[228] In 2023, luggage storage company Bounce gave Croatia the highest solo travel index in the world (7.58),[229] while a joint Pinterest and Zola wedding trends report from 2023 put Croatia among the most popular honeymoon destinations.[230]

Infrastructure

Transport

This section needs to be updated. (December 2020) |

The motorway network was largely built in the late 1990s and the 2000s (decade). As of December 2020, Croatia had completed 1,313.8 kilometres (816.4 miles) of motorways, connecting Zagreb to other regions and following various European routes and four Pan-European corridors.[231][232][233] The busiest motorways are the A1, connecting Zagreb to Split and the A3, passing east to west through northwest Croatia and Slavonia.[234]

A widespread network of state roads in Croatia acts as motorway feeder roads while connecting major settlements. The high quality and safety levels of the Croatian motorway network were tested and confirmed by EuroTAP and EuroTest programmes.[235][236]

Croatia has an extensive rail network spanning 2,604 kilometres (1,618 miles), including 984 kilometres (611 miles) of electrified railways and 254 kilometres (158 miles) of double track railways (as of 2017[update]).[237] The most significant railways in Croatia are within the Pan-European transport corridors Vb and X connecting Rijeka to Budapest and Ljubljana to Belgrade, both via Zagreb.[231] Croatian Railways operates all rail services.[238]

The construction of 2.4-kilometre-long Pelješac Bridge, the biggest infrastructure project in Croatia connects the two halves of Dubrovnik-Neretva County and shortens the route from the West to the Pelješac peninsula and the islands of Korčula and Lastovo by more than 32 km. The construction of the Pelješac Bridge started in July 2018 after Croatian road operator Hrvatske ceste (HC) signed a 2.08 billion kuna deal for the works with a Chinese consortium led by China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC). The project is co-financed by the European Union with 357 million euro. The construction was completed in July 2022.[239]

There are international airports in Dubrovnik, Osijek, Pula, Rijeka, Split, Zadar, and Zagreb.[240] The largest and busiest is Franjo Tuđman Airport in Zagreb.[241][better source needed] As of January 2011[update], Croatia complies with International Civil Aviation Organization aviation safety standards and the Federal Aviation Administration upgraded it to Category 1 rating.[242]

Ports

The busiest cargo seaport is the Port of Rijeka. The busiest passenger ports are Split and Zadar.[243][244] Many minor ports serve ferries connecting numerous islands and coastal cities with ferry lines to several cities in Italy.[245] The largest river port is Vukovar, located on the Danube, representing the nation's outlet to the Pan-European transport corridor VII.[231][246]

Energy

610 kilometres (380 miles) of crude oil pipelines serve Croatia, connecting the Rijeka oil terminal with refineries in Rijeka and Sisak, and several transhipment terminals. The system has a capacity of 20 million tonnes per year.[247] The natural gas transportation system comprises 2,113 kilometres (1,313 miles) of trunk and regional pipelines, and more than 300 associated structures, connecting production rigs, the Okoli natural gas storage facility, 27 end-users and 37 distribution systems.[248] Croatia also plays an important role in regional energy security. The floating liquefied natural gas import terminal off Krk island LNG Hrvatska commenced operations on January 1, 2021, positioning Croatia as a regional energy leader and contributing to diversification of Europe's energy supply.[16]

In 2010, Croatian energy production covered 85% of nationwide natural gas and 19% of oil demand.[249] In 2016, Croatia's primary energy production involved natural gas (24.8%), hydropower (28.3%), crude oil (13.6%), fuelwood (27.6%), and heat pumps and other renewable energy sources (5.7%).[250] In 2017, net total electrical power production reached 11,543 GWh, while it imported 12,157 GWh or about 40% of its electric power energy needs.[251]

Krško Nuclear Power Plant (Slovenia) supplies a large part of Croatian imports. 50% is owned by Hrvatska elektroprivreda, providing 15% of Croatia's electricity.[252]

Demographics

This section needs to be updated. (September 2022) |

With an estimated population of 3.87 million in 2021,[253] Croatia ranks 127th by population in the world.[citation needed] Its 2018 population density was 72.9 inhabitants per square kilometre, making Croatia one of the more sparsely populated European countries.[254] The overall life expectancy in Croatia at birth was 76.3 years in 2018.[212]

The total fertility rate of 1.41 children per mother, is one of the lowest in the world, far below the replacement rate of 2.1, it remains considerably below the high of 6.18 children rate in 1885.[212][255] Croatia's death rate has continuously exceeded its birth rate since 1998.[256] Croatia subsequently has one of the world's oldest populations, with an average age of 43.3 years.[257] The population rose steadily from 2.1 million in 1857 until 1991, when it peaked at 4.7 million, with the exceptions of censuses taken in 1921 and 1948, i.e. following the world wars.[258] The natural growth rate is negative[157] with the demographic transition completed in the 1970s.[259] In recent years, the Croatian government has been pressured to increase permit quotas for foreign workers, reaching an all-time high of 68.100 in 2019.[260] In accordance with its immigration policy, Croatia is trying to entice emigrants to return.[261] From 2008 to 2018, Croatia's population dropped by 10%.[262]

The population decrease was greater a result of war for independence. The war displaced large numbers of the population and emigration increased. In 1991, in predominantly occupied areas, more than 400,000 Croats were either removed from their homes by Serb forces or fled the violence.[263] During the war's final days, about 150–200,000 Serbs fled before the arrival of Croatian forces during Operation Storm.[123][264] After the war, the number of displaced persons fell to about 250,000. The Croatian government cared for displaced persons via the social security system and the Office of Displaced Persons and Refugees.[265] Most of the territories abandoned during the war were settled by Croat refugees from Bosnia and Herzegovina, mostly from north-western Bosnia, while some displaced people returned to their homes.[266][267]

According to the 2013 United Nations report, 17.6% of Croatia's population were immigrants.[268] According to the 2021 census, the majority of inhabitants are Croats (91.6%), followed by Serbs (3.2%), Bosniaks (0.62%), Roma (0.46%), Albanians (0.36%), Italians (0.36%), Hungarians (0.27%), Czechs (0.20%), Slovenes (0.20%), Slovaks (0.10%), Macedonians (0.09%), Germans (0.09%), Montenegrins (0.08%), and others (1.56%).[7] Approximately 4 million Croats live abroad.[269]

| Rank | Name | Counties | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Zagreb  Split |

1 | Zagreb | Zagreb | 790,017 |  Rijeka  Osijek | ||||

| 2 | Split | Split-Dalmatia | 178,102 | ||||||

| 3 | Rijeka | Primorje-Gorski Kotar | 128,624 | ||||||

| 4 | Osijek | Osijek-Baranja | 108,048 | ||||||

| 5 | Zadar | Zadar | 75,062 | ||||||

| 6 | Pula | Istria | 57,460 | ||||||

| 7 | Slavonski Brod | Brod-Posavina | 59,141 | ||||||

| 8 | Karlovac | Karlovac | 55,705 | ||||||

| 9 | Varaždin | Varaždin | 46,946 | ||||||

| 10 | Šibenik | Šibenik-Knin | 46,332 | ||||||

Religion

Croatia has no official religion. Freedom of religion is a Constitutional right that protects all religious communities as equal before the law and separated from the state.

According to the 2011 census, 91.36% of Croatians identify as Christian; of these, Catholics make up the largest group, accounting for 86.28% of the population, after which follows Eastern Orthodoxy (4.44%), Protestantism (0.34%), and other Christians (0.30%).The largest religion after Christianity is Islam (1.47%). 4.57% of the population describe themselves as non-religious.[271] In the Eurostat Eurobarometer Poll of 2010, 69% of the population responded that "they believe there is a God".[272] In a 2009 Gallup poll, 70% answered yes to the question "Is religion an important part of your daily life?"[273] However, only 24% of the population attends religious services regularly.[274]

Languages

Croatian is the official language of the Republic of Croatia. Minority languages are in official use in local government units where more than a third of the population consists of national minorities or where local enabling legislation applies. Those languages are Czech, Hungarian, Italian, Serbian, and Slovak.[275][276] The following minority languages are also recognised: Albanian, Bosnian, Bulgarian, German, Hebrew, Macedonian, Montenegrin, Polish, Romanian, Istro-Romanian, Romani, Russian, Rusyn, Slovene, Turkish, and Ukrainian.[276]

According to the 2011 Census, 95.6% of citizens declared Croatian as their native language, 1.2% declared Serbian as their native language, while no other language reaches more than 0.5%.[2] Croatian is a member of the South Slavic languages of Slavic languages group and is written using the Latin alphabet. There are three major dialects spoken on the territory of Croatia, with standard Croatian based on the Shtokavian dialect. The Chakavian and Kajkavian dialects are distinguished from Shtokavian by their lexicon, phonology and syntax.[277]

A 2011 survey revealed that 78% of Croats claim knowledge of at least one foreign language.[278] According to a 2005 EC survey, 49% of Croats speak English as the second language, 34% speak German, 14% speak Italian, and 10% speak French. Russian is spoken by 4%, and 2% of Croats speak Spanish. However several large municipalities support minority languages. A majority of Slovenes (59%) have some knowledge of Croatian.[279] The country is a part of various language-based international associations, most notably the European Union Language Association.[280]

Education

This section needs to be updated. (December 2020) |

Literacy in Croatia stands at 99.2 per cent.[281] Primary education in Croatia starts at the age of six or seven and consists of eight grades. In 2007 a law was passed to increase free, noncompulsory education until 18 years of age. Compulsory education consists of eight grades of elementary school.

Secondary education is provided by gymnasiums and vocational schools. As of 2019, there are 2,103 elementary schools and 738 schools providing various forms of secondary education.[282] Primary and secondary education are also available in languages of recognised minorities in Croatia, where classes are held in Czech, Hungarian, Italian, Serbian, German and Slovak languages.[283]

There are 133 elementary and secondary level music and art schools,[284] as well as 83 elementary and 44 secondary schools for disabled children and youth[285] and 11 elementary and 52 secondary schools for adults.[286] Nationwide leaving exams (Croatian: državna matura) were introduced for secondary education students in the school year 2009–2010. It comprises three compulsory subjects (Croatian language, mathematics, and a foreign language) and optional subjects and is a prerequisite for university education.[287] Croatia has eight public universities and two private universities.[288] The University of Zadar, the first university in Croatia, was founded in 1396 and remained active until 1807, when other institutions of higher education took over until the foundation of the renewed University of Zadar in 2002.[289] The University of Zagreb, founded in 1669, is the oldest continuously operating university in Southeast Europe.[290] There are also 15 polytechnics, of which two are private, and 30 higher education institutions, of which 27 are private.[288] In total, there are 131 institutions of higher education in Croatia, attended by more than 160 thousand students.[291]

There are 254 companies, government or education system institutions and non-profit organisations in Croatia pursuing scientific research and development of technology. Combined, they spent around 3 billion kuna (€400 million) gross and employed 11,801 full-time research staff in 2016.[292] Among the scientific institutes operating in Croatia, the largest is the Ruđer Bošković Institute in Zagreb.[293] The Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Zagreb is a learned society promoting language, culture, arts and science from its inception in 1866.[294] Croatia was ranked 44th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[295]

The European Investment Bank provided digital infrastructure and equipment to around 150 primary and secondary schools in Croatia. Twenty of these schools got specialised assistance in the form of gear, software, and services to help them integrate the teaching and administrative operations.[296][297]

Healthcare

Croatia has a universal health care system, whose roots can be traced back to the Hungarian-Croatian Parliament Act of 1891, providing a form of mandatory insurance of all factory workers and craftsmen.[298] The population is covered by a basic health insurance plan provided by statute and optional insurance. In 2017, annual healthcare related expenditures reached 22.2 billion kuna (around €3.0 billion).[299] Healthcare expenditures comprise only 0.6% of private health insurance and public spending.[300] In 2017, Croatia spent around 6.6% of its GDP on healthcare.[301] In 2020, Croatia ranked 41st in the world in life expectancy with 76.0 years for men and 82.0 years for women, and it had a low infant mortality rate of 3.4 per 1,000 live births.[302]

There are hundreds of healthcare institutions in Croatia, including 75 hospitals, and 13 clinics with 23,049 beds. The hospitals and clinics care for more than 700 thousand patients per year and employ 6,642 medical doctors, including 4,773 specialists.[303] There is total of 69,841 health workers.[304] There are 119 emergency units in health centres, responding to more than a million calls.[305] The principal cause of death in 2016 was cardiovascular disease at 39.7% for men and 50.1% for women, followed by tumours, at 32.5% for men and 23.4% for women.[306] In 2016 it was estimated that 37.0% of Croatians are smokers.[307] According to 2016 data, 24.40% of the Croatian adult population is obese.[308]

Language

Standard Croatian is the official language of the Republic of Croatia,[309] and became the 24th official language of the European Union upon its accession in 2013.[310][311]

Croatian replaced Latin as the official language of the Croatian government in the 19th century.[312] Following the Vienna Literary Agreement in 1850, the language and its Latin script underwent reforms to create an unified "Croatian or Serbian" or "Serbo-Croatian" standard, which under various names became the official language of Yugoslavia.[313] In SFR Yugoslavia, from 1972 to 1989, the language was constitutionally designated as the "Croatian literary language" and the "Croatian or Serbian language". It was the result of a resistance to and secession from "Serbo-Croatian" in the form of the Declaration on the Status and Name of the Croatian Literary Language as part of the Croatian Spring.[314] Since gaining independence in the early 1990s, the Republic of Croatia constitutionally designates the language as "Croatian language" and regulates it through linguistic prescription. The long-standing aspiration to developing its own expressions, thus enriching itself, as opposed to taking over foreign solutions in the form of loanwords has been described as Croatian linguistic purism.[315]

Croatia introduced in 2021 a new model of linguistic categorisation of Bunjevac dialect (as New-Shtokavian Ikavian dialects of the Shtokavian dialect of the Croatian language) in three sub-branches: Dalmatian (also called Bosnian-Dalmatian), Danubian (also called Bunjevac), and Littoral-Lika.[316][317] Its speakers largely use the Latin alphabet and are living in parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, different parts of Croatia, southern parts (inc. Budapest) of Hungary as well in the autonomous province Vojvodina of Serbia. The Institute of Croatian Language and Linguistics added the Bunjevac dialect to the List of Protected Intangible Cultural Heritage of the Republic of Croatia on 8 October 2021.[318][319][undue weight? ]

Culture

Because of its geographical position, Croatia represents a blend of four different cultural spheres. It has been a crossroads of influences from western culture and the east since the schism between the Western Roman Empire and the Byzantine Empire, and also from Central Europe and Mediterranean culture.[321] The Illyrian movement was the most significant period of national cultural history, as the 19th century proved crucial to the emancipation of Croatians and saw unprecedented developments in all fields of art and culture, giving rise to many historical figures.[63]

The Ministry of Culture is tasked with preserving the nation's cultural and natural heritage and overseeing its development. Further activities supporting the development of culture are undertaken at the local government level.[322] The UNESCO's World Heritage List includes ten sites in Croatia. The country is also rich with intangible culture and holds 15 of UNESCO's World's intangible culture masterpieces, ranking fourth in the world.[323] A global cultural contribution from Croatia is the necktie, derived from the cravat originally worn by the 17th-century Croatian mercenaries in France.[324][325]

In 2019, Croatia had 95 professional theatres, 30 professional children's theatres, and 51 amateur theatres visited by more than 2.27 million viewers per year. Professional theatres employ 1,195 artists. There are 42 professional orchestras, ensembles, and choirs, attracting an annual attendance of 297 thousand. There are 75 cinemas with 166 screens and attendance of 5.026 million.[326]

Croatia has 222 museums, visited by more than 2.71 million people in 2016. Furthermore, there are 1,768 libraries, containing 26.8 million volumes, and 19 state archives.[327] The book publishing market is dominated by several major publishers and the industry's centrepiece event—Interliber exhibition held annually at Zagreb Fair.[328]

Arts, literature, and music

Architecture in Croatia reflects influences of bordering nations. Austrian and Hungarian influence is visible in public spaces and buildings in the north and the central regions, architecture found along coasts of Dalmatia and Istria exhibits Venetian influence.[329] Squares named after culture heroes, parks, and pedestrian-only zones, are features of Croatian towns and cities, especially where large scale Baroque urban planning took place, for instance in Osijek (Tvrđa), Varaždin, and Karlovac.[330][331] The subsequent influence of the Art Nouveau was reflected in contemporary architecture.[332] The architecture is the Mediterranean with a Venetian and Renaissance influence in major coastal urban areas exemplified in works of Giorgio da Sebenico and Nicolas of Florence such as the Cathedral of St. James in Šibenik. The oldest preserved examples of Croatian architecture are the 9th-century churches, with the largest and the most representative among them being Church of St. Donatus in Zadar.[333][334]

Besides the architecture encompassing the oldest artworks, there is a history of artists in Croatia reaching the Middle Ages. In that period the stone portal of the Trogir Cathedral was made by Radovan, representing the most important monument of Romanesque sculpture from Medieval Croatia. The Renaissance had the greatest impact on the Adriatic Sea coast since the remainder was embroiled in the Hundred Years' Croatian–Ottoman War. With the waning of the Ottoman Empire, art flourished during the Baroque and Rococo. The 19th and 20th centuries brought affirmation of numerous Croatian artisans, helped by several patrons of the arts such as bishop Josip Juraj Strossmayer.[335] Croatian artists of the period achieving renown were Vlaho Bukovac, Ivan Meštrović, and Ivan Generalić.[333][336]

The Baška tablet, a stone inscribed with the glagolitic alphabet found on the Krk island and dated to c. 1100, is considered to be the oldest surviving prose in Croatian.[337] The beginning of more vigorous development of Croatian literature is marked by the Renaissance and Marko Marulić. Besides Marulić, Renaissance playwright Marin Držić, Baroque poet Ivan Gundulić, Croatian national revival poet Ivan Mažuranić, novelist, playwright, and poet August Šenoa, children's writer Ivana Brlić-Mažuranić, writer and journalist Marija Jurić Zagorka, poet and writer Antun Gustav Matoš, poet Antun Branko Šimić, expressionist and realist writer Miroslav Krleža, poet Tin Ujević and novelist, and short story writer Ivo Andrić are often cited as the greatest figures in Croatian literature.[338][339]

Croatian music varies from classical operas to modern-day rock. Vatroslav Lisinski created the country's first opera, Love and Malice, in 1846. Ivan Zajc composed more than a thousand pieces of music, including masses and oratorios. Pianist Ivo Pogorelić has performed across the world.[336]

Media

In Croatia, the Constitution guarantees the freedom of the press and the freedom of speech.[340] Croatia ranked 64th in the 2019 Press Freedom Index report compiled by Reporters Without Borders which noted that journalists who investigate corruption, organised crime or war crimes face challenges and that the Government was trying to influence the public broadcaster HRT's editorial policies.[341] In its 2019 Freedom in the World report, the Freedom House classified freedoms of press and speech in Croatia as generally free from political interference and manipulation, noting that journalists still face threats and occasional attacks.[342] The state-owned news agency HINA runs a wire service in Croatian and English on politics, economics, society, and culture.[343]

As of January 2021[update], there are thirteen nationwide free-to-air DVB-T television channels, with Croatian Radiotelevision (HRT) operating four, RTL Televizija three, and Nova TV operating two channels, and the Croatian Olympic Committee, Kapital Net d.o.o., and Author d.o.o. companies operate the remaining three.[345] Also, there are 21 regional or local DVB-T television channels.[346] The HRT is also broadcasting a satellite TV channel.[347] In 2020, there were 147 radio stations and 27 TV stations in Croatia.[348][349] Cable television and IPTV networks are gaining ground. Cable television already serves 450 thousand people, around 10% of the total population of the country.[350][351]

In 2010, 267 newspapers and 2,676 magazines were published in Croatia.[348] The print media market is dominated by the Croatian-owned Hanza Media and Austrian-owned Styria Media Group who publish their flagship dailies Jutarnji list, Večernji list and 24sata. Other influential newspapers are Novi list and Slobodna Dalmacija.[352][353] In 2020, 24sata was the most widely circulated daily newspaper, followed by Večernji list and Jutarnji list.[354][355]

Croatia's film industry is small and heavily subsidised by the government, mainly through grants approved by the Ministry of Culture with films often being co-produced by HRT.[356][357] Croatian cinema produces between five and ten feature films per year.[358] Pula Film Festival, the national film awards event held annually in Pula, is the most prestigious film event featuring national and international productions.[359] Animafest Zagreb, founded in 1972, is the prestigious annual film festival dedicated to the animated film. The first greatest accomplishment by Croatian filmmakers was achieved by Dušan Vukotić when he won the 1961 Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film for Ersatz (Croatian: Surogat).[360] Croatian film producer Branko Lustig won the Academy Awards for Best Picture for Schindler's List and Gladiator.[361]

Cuisine

Croatian traditional cuisine varies from one region to another. Dalmatia and Istria have culinary influences of Italian and other Mediterranean cuisines which prominently feature various seafood, cooked vegetables and pasta, and condiments such as olive oil and garlic. Austrian, Hungarian, Turkish, and Balkan culinary styles influenced continental cuisine. In that area, meats, freshwater fish, and vegetable dishes are predominant.[362]

There are two distinct wine-producing regions in Croatia. The continental in the northeast of the country, especially Slavonia, produces premium wines, particularly whites. Along the north coast, Istrian and Krk wines are similar to those in neighbouring Italy, while further south in Dalmatia, Mediterranean-style red wines are the norm.[362] Annual production of wine exceeds 72 million litres as of 2017[update].[363] Croatia was almost exclusively a wine-consuming country up until the late 18th century when a more massive beer production and consumption started.[364] The annual consumption of beer in 2020 was 78.7 litres per capita which placed Croatia in 15th place among the world's countries.[365]

There are 11 restaurants in Croatia with a Michelin star and 89 restaurants bearing some of the Michelin's marks.[366]

Sports

This section needs to be updated. (January 2021) |

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2022) |

There are more than 400,000 active sportspeople in Croatia.[367] In 2006, there were over 277 thousand members of sports associations and nearly 3,600 are chess and contract bridge association members.[368] Association football is the most popular sport. The Croatian Football Federation (Croatian: Hrvatski nogometni savez), with more than 118,000 registered players, is the largest sporting association.[369] The Croatian national football team came in third in 1998 and 2022 and second in the 2018 FIFA World Cup. The Prva HNL football league attracts the highest average attendance of any professional sports league. In season 2010–11, it attracted 458,746 spectators.[370]

Croatian athletes competing at international events since Croatian independence in 1991 won 44 Olympic medals, including 15 gold medals.[371] Also, Croatian athletes won 16 gold medals at world championships, including four in athletics at the World Championships in Athletics. Croatia won their first major trophy at the 2003 World Men's Handball Championship. In tennis, they won Davis Cup in 2005 and 2018. Croatia's most successful male players Goran Ivanišević and Marin Čilić have both won Grand Slam titles and have got into the top 3 of the ATP rankings. Ognjen Cvitan won the World Junior Chess Championship in 1981. In waterpolo, they have three world titles. Iva Majoli became the first Croatian female player to win the French Open when she won it in 1997. Croatia hosted several major sports competitions, including the 2009 World Men's Handball Championship, the 2007 World Table Tennis Championships, the 2000 World Rowing Championships, the 1987 Summer Universiade, the 1979 Mediterranean Games, and several European Championships, including the 2000 and 2018 European Men's Handball Championship.

The governing sports authority is the Croatian Olympic Committee (Croatian: Hrvatski olimpijski odbor), founded on 10 September 1991 and recognised by the International Olympic Committee since 17 January 1992, in time to permit the Croatian athletes to appear at the 1992 Winter Olympics in Albertville, France representing the newly independent nation for the first time at the Olympic Games.[372]

See also

Explanatory notes

- ^ In the recognised minority languages of Croatia and the most spoken second languages:

- ^ Apart from Croatian, counties have official regional languages that are used for official government business and commercially. In Istria County a minority is Italian-speaking[1][2] while select counties bordering Serbia speak standard Serbian.[3] Other notable—albeit significantly less-present—minority languages in Croatia include: Czech, Hungarian, and Slovak.

- ^ The writing system of Croatia is legally protected by the Croatian Parliament. Efforts to recognise minority scripts, pursuant to international law, on a local level, have been met with nationalist opposition.

- ^ IPA transcription of "Republika Hrvatska": (Croatian pronunciation: [ˈrepǔblika ˈxř̩ʋaːtskaː]).

Citations

- ^ "Europska povelja o regionalnim ili manjinskim jezicima" (in Croatian). Ministry of Justice and Public Administration (Croatia). 4 November 2011. Archived from the original on 27 December 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Population by Mother Tongue, by Towns/Municipalities, 2011 Census". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings 2011. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. December 2012.

- ^ "Is Serbo-Croatian a language?". The Economist. 10 April 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2018.

- ^ "Share of Croats in Croatia increases as census results published". 22 September 2022.

- ^ "Zakon o blagdanima, spomendanima i neradnim danima u Republici Hrvatskoj" [Law of Holidays, Memorial Days and Non-Working Days in the Republic of Croatia]. Narodne Novine (in Croatian). 15 November 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "POPULATION ESTIMATE OF THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA, 2022". podaci.dzs.hr. 8 September 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2023.

- ^ a b c "Population by Towns/Municipalities, 2021 Census". Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in 2021. Zagreb: Croatian Bureau of Statistics. 2022.

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024 Edition. (Croatia)". www.imf.org. International Monetary Fund. 16 April 2024. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ "Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income – EU-SILC survey". ec.europa.eu. Eurostat. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/2024" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 14 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ "Hrvatski sabor – Povijest". Archived from the original on 6 March 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ "IMF World Economic Outlook". Retrieved 14 April 2023.

- ^ "Croatia tourist arrivals 2022". Statista. Retrieved 5 November 2023.

- ^ "International tourism, The World Bank". Retrieved 14 April 2023.