Emirate of Sicily

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Emirate of Sicily إمارة صقلية (Arabic) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 831–1091 | |||||||||

Italy in 1000. The Emirate of Sicily is coloured in light green. | |||||||||

| Status |

| ||||||||

| Capital | Balarm (Palermo) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Sicilian Arabic, Byzantine Greek, Berber languages, Judeo-Arabic | ||||||||

| Religion | Shia Islam (Kalbids) Sunni Islam Chalcedonian Christianity Judaism[1] | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||||

• Established | 831 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1091 | ||||||||

| Currency | Tarì, dirham | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Italy Malta | ||||||||

| Historical Arab states and dynasties |

|---|

|

The Emirate of Sicily or Fatimid Sicily (Arabic: إِمَارَة صِقِلِّيَة, romanized: ʾImārat Ṣiqilliya) was an Islamic kingdom that ruled the Muslim territories on the island of Sicily between 831 and 1091.[2][failed verification] Its capital was Palermo (Arabic: Balarm), which, during this period, became a major cultural and political center of the Muslim world.[3]

Sicily was part of the Byzantine Empire when Muslim forces from Ifriqiya began launching raids in 652. Through a prolonged series of conflicts from 827 to 902, they gradually conquered the entirety of Sicily, with only the stronghold of Rometta, in the far northeast, holding out until 965.

Sicily became multiconfessional and multilingual, developing a distinct Arab-Byzantine culture that combined elements of its Islamic Arab and Berber migrants with those of the local Latin-Romance, Greek-Byzantine and Jewish communities. Beginning in the early eleventh century, the Emirate began to fracture from internal strife and dynastic disputes. Christian Norman mercenaries under Roger I ultimately conquered the island, founding the County of Sicily in 1071; the last Muslim city on the island, Noto, fell in 1091, marking the end of Islamic rule in Sicily.

As the first Count of Sicily, Roger maintained a relative degree of tolerance and multiculturalism; Sicilian Muslims remained citizens of the County and the subsequent Kingdom of Sicily. Until the late 12th century, and probably as late as the 1220s, Muslims formed a majority of the island's population, except in the northeast region of Val Demone, which had remained predominantly Byzantine Greek and Christian, even during Islamic rule.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10] But by the mid thirteenth century, Muslims who had not already left or converted to Christianity were expelled, ending roughly four hundred years of Islamic presence in Sicily.

Over two centuries of Islamic rule by the Emirate has left some traces in modern Sicily. Minor Arabic influence remains in the Sicilian language and in local place names; a much larger influence is in the Maltese language that derives from Siculo-Arabic. Other cultural remnants can be found in the island's agricultural methods and crops, the local cuisine, and architecture.[11]

Background[edit]

Due to its strategic location in the center of the Mediterranean, Sicily had a long history of being settled and contested by various civilizations. Greek and Phoenician colonies were present at least by the ninth century BC, and skirmished intermittently for centuries. Conflicts continued on a larger scale in the sixth through third centuries BC between the Carthaginians and the Sicilian Greeks, most of all the powerful city-state of Syracuse. The Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage saw Sicily serve as a major power base and theater of war for both sides, before the island was finally incorporated into the Roman Republic and Empire. By the fifth century AD, Sicily had become thoroughly Romanized and Christianized after nearly seven hundred years of Roman rule. But amid the decay of the Western Roman Empire, it fell to the Germanic Ostrogoths following Theodoric the Great's conquest of most of Italy in 488.

First Muslim attempts to conquer Sicily[edit]

In 535, Emperor Justinian I reconquered Sicily for the Roman Empire, which by then was ruled from Constantinople. As the power of what is now known as the Byzantine Empire waned in the West, a new and expansionist power was emerging in the Middle East: the Rashidun Caliphate, the first major Muslim state to emerge following the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad in 632. Over a period of twenty five years, the caliphate succeeded in annexing much of the Persian Sasanian Empire and former Roman territories in the Levant and North Africa. In 652, under Caliph Uthman, an invasion captured most of the island, but Muslims occupation was short-lived, as they left following his death.[citation needed]

By the end of the seventh century, with the Umayyad conquest of North Africa, the Muslims had captured the nearby port city of Carthage, allowing them to build shipyards and a permanent base from which to launch more sustained attacks.[12]

Around 700, the island of Pantelleria was captured by Umayyads, and it was only discord among the Muslims that prevented an attempted invasion of Sicily at that time. Instead, trading agreements were arranged with the Byzantines, and Muslim merchants were allowed to trade goods at Sicilian ports.[citation needed]

The first true attempt at conquest was launched in 740; in that year the Muslim prince Habib, who had participated in the 728 attack, successfully captured Syracuse. Ready to conquer the whole island, they were however forced to return to Tunisia by a Berber revolt. A second attack in 752 aimed only to sack the same city.[citation needed]

Revolt of Euphemius and gradual Muslim conquest of the island[edit]

In 826, Euphemius, the commander of the Byzantine fleet of Sicily, forced a nun to marry him. Emperor Michael II caught wind of the matter and ordered that General Constantine end the marriage and cut off Euphemius' nose. Euphemius rose up, killed Constantine and then occupied Syracuse; he in turn was defeated and driven out to North Africa.[2] He offered rule of Sicily over to Ziyadat Allah, the Aghlabid Emir of Tunisia, in return for a place as a general and safety; the Emir agreed, offering to give Euphemius the island in exchange for a yearly tribute. The conquest was entrusted to the 70-year-old qadi Asad ibn al-Furat, who led a force 10,000 infantry, 700 cavalry and 100 ships.[2] Reinforced by the Muslims, Euphemius' ships landed at Mazara del Vallo, where the first battle against loyalist Byzantine troops occurred on July 15, 827, resulting in an Aghlabid victory.

Asad subsequently conquered the southern shore of the island and laid siege to Syracuse. After year-long siege, and an attempted mutiny, his troops were able to defeat a large army sent from Palermo, backed by a Venetian fleet led by Doge Giustiniano Participazio. A sudden outbreak of plague killed many of the Muslim troops, as well as Asad himself, forcing the Muslims to retreat to the castle Mineo. They later renewed their offensive, but failed to conquer Castrogiovanni (modern Enna) where Euphemius was killed, forcing them to retreat back to their stronghold at Mazara.

In 830, the remaining Muslims of Sicily received a strong reinforcement of 30,000 Ifriqiyan and Andalusian troops. The Iberian Muslims defeated the Byzantine commander Teodotus between July and August of that year, but again a plague forced them to return to Mazara and later Ifriqiya. However, Ifriqiyan units sent to besiege the Sicilian capital of Palermo managed to capture it after a year long siege in September 831.[13] Palermo was made the Muslim capital of Sicily, renamed al-Madinah ("The City").[14]

The conquest was an incremental, see-saw affair; with considerable resistance and many internal struggles, it took over a century for Byzantine Sicily to be fully conquered. Syracuse held out until 878, followed by Taormina in 902, and finally, Rometta, the last Byzantine outpost, in 965.[2]

Period as an emirate[edit]

In succession, Sicily was ruled by the Sunni Aghlabid dynasty in Tunisia and the Shiite Fatimids in Egypt. However, throughout this period, Sunni Muslims formed the majority of the Muslim community in Sicily,[15] with most (if not all) of the people of Palermo being Sunni,[16] leading to their hostility to the Shia Kalbids.[17] The Sunni population of the island was replenished following sectarian rebellions across north Africa from 943–947 against the Fatimids' harsh religious policies, leading to several waves of refugees fleeing to Sicily in an attempt to escape Fatimid retaliation.[18] The Byzantines took advantage of temporary discord to occupy the eastern end of the island for several years.

After suppressing a revolt the Fatimid caliph Ismail al-Mansur appointed al-Hasan al-Kalbi (948–964) as Emir of Sicily. He successfully managed to control the continuously revolting Byzantines and founded the Kalbid dynasty. Raids into Southern Italy continued under the Kalbids into the 11th century, and in 982 a German army under Otto II, Holy Roman Emperor was defeated near Crotone in Calabria. With Emir Yusuf al-Kalbi (986–998) a period of steady decline began. Under al-Akhal (1017–1037) the dynastic conflict intensified, with factions within the ruling family allying themselves variously with the Byzantine Empire and the Zirids. After this period, Al-Mu'izz ibn Badis attempted to annex the island for the Zirids, while intervening in the affairs of the feuding Muslims; however, the attempt ultimately failed.[19]

Sicily under Arab rule[edit]

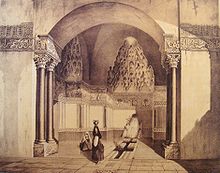

The new Arab rulers initiated land reforms, which in turn increased productivity and encouraged the growth of smallholdings, a dent to the dominance of the landed estates. The Arabs further improved irrigation systems through Qanats. Introducing oranges, lemons, pistachio and sugarcane to Sicily. A description of Palermo was given by Ibn Hawqal, a Baghdad merchant who visited Sicily in 950. A walled suburb called the Kasr (the palace) is the center of Palermo until today, with the great Friday mosque on the site of the later Roman cathedral. The suburb of Al-Khalisa (Kalsa) contained the Sultan's palace, baths, a mosque, government offices, and a private prison. Ibn Hawqual reckoned 7,000 individual butchers trading in 150 shops. The population of the city during this period is uncertain, as figures given by Arab writers during the era were unreliable. Paul Bairoch estimated Palermo's population at 350,000 in the 11th century, while other historians like Stephan R. Epstein estimated it to be closer to 60,000. Based on al-Maqdisi's statement that Palermo was larger than Old Cairo, Kenneth Meyer Setton put the figure above 100,000 but below 250,000.[20][21] Around 1330, Palermo's population stood at 51,000.[22]

Arab traveler, geographer, and poet Ibn Jubair visited the area in the end of the 12th century and described Al-Kasr and Al-Khalisa (Kalsa):

The capital is endowed with two gifts, splendor and wealth. It contains all the real and imagined beauty that anyone could wish. Splendor and grace adorn the piazzas and the countryside; the streets and highways are wide, and the eye is dazzled by the beauty of its situation. It is a city full of marvels, with buildings similar to those of Córdoba, built of limestone. A permanent stream of water from four springs runs through the city. There are so many mosques that they are impossible to count. Most of them also serve as schools. The eye is dazzled by all this splendor.

Throughout this reign, revolts by Byzantine Sicilians occurred, especially in the east, and part of the lands were even re-occupied before being quashed.[23]

The local population conquered by the Muslims were Greek-speaking and Latin-speaking Byzantine Christians,[24] but there were also a significant number of Jews.[25] The Orthodox and Catholic populations were members of one Church until the events of 1054 began to separate them, the sack of 1204 being the last straw as far as the Byzantine "Orthodox" were concerned.

Christians and Jews were tolerated under Muslim rule as dhimmis, but were subject to some restrictions. The dhimmis were also required to pay the jizya, or poll tax, and the kharaj or land tax, but were exempt from the tax that Muslims had to pay (Zakaat). Under Arab rule there were different categories of Jizya payers, but their common denominator was the payment of the Jizya as a mark of subjection to Muslim rule in exchange for protection against foreign and internal aggression. The conquered population could avoid this subservient status by converting to Islam. About half the population was Muslim at the time of the Norman Conquest. The co-existence with the conquered population fell apart after the reconquest of Sicily starting in the 1160s and particularly following the death of King William II of Sicily in 1189. The policy of oppression visited upon Christians was applied to Muslims.

Administration[edit]

The emir was in charge of the army, administration, justice and minted money. It is also very likely that a tiraz was active in Palermo, a workshop in which the sovereign authorities had fabrics of great value created (often granted as a sign of appreciation to their subjects to reward them for their work or as a gift of the reception of foreign embassies). The Emir - who resided in today's Royal Palace - appointed the governors of the major cities, the most important judges (qāḍī) and the arbitrators capable of resolving minor disputes between individuals (hakam). There was also an assembly of notables called giamà'a that supported and in some cases replaced the emir in decisions.

The Muslim domination across the island was not consistent and the division into the three valleys served to distinguish the different approaches to government. In fact, western Sicily was more Islamized and the numerical presence of the Arabs was much greater than the other parts. In Val Demone the difficulties in the conquest and the resistance of the population resulted in a focus concentrated on tax collection and the maintenance of public order.

The fighters or junud in conquering the lands obtained four-fifths as booty (fai) and one fifth was reserved for the state or the local governor (the khums), following the rules of Islamic law . However this rule was not always respected and in many areas such as that of Agrigento the new owners would not have had the right. But it must be said that this distribution of the lands brought about the end of the large estates and the possibility of better exploitation of the lands. New crops were thus introduced where only wheat had been grown for centuries. Sugarcane, vegetables, citrus fruits, dates and mulberry trees appeared and mining exploitation began.[26]

Coinage[edit]

The coin introduced by the Arabs was the dinar, in gold and weighing 4.25 grams. The dirhem was silver and weighed 2.97 grams. The Aghlabites introduced the solidus in gold and the follis in copper. While following the conquest of Palermo in 886 the kharruba was coined which was worth 1/6 of a dirhem.

Decline and "Taifa" period[edit]

By the 11th century mainland southern Italian powers were hiring Norman mercenaries, who were Christian descendants of the Vikings; it was the Normans under Roger de Hauteville, who became Roger I of Sicily, that captured Sicily from the Muslims.[2] In 1038, a Byzantine army under George Maniaces crossed the strait of Messina, and included a corps of Normans. After another decisive victory in the summer of 1040, Maniaces halted his march to lay siege to Syracuse. Despite his conquest of the latter, Maniaces was removed from his position, and the subsequent Muslim counter-offensive reconquered all the cities captured by the Byzantines.[23] The Norman Robert Guiscard, son of Tancred, then conquered Sicily in 1060 after taking Apulia and Calabria, while his brother Roger de Hauteville occupied Messina with an army of 700 knights.

The Emirate of Sicily began to fragment as intra-dynastic quarrels took place within the Muslim regime.[2] In 1044, under emir Hasan al-Samsam, the island fragmented into four qadits, or small fiefdoms: the qadit of Trapani, Marsala, Mazara and Sciacca led by Abdallah ibn Mankut; that of Girgenti, Castrogiovanni and Castronuovo under Ibn al-Hawwàs; Catania held by Ibn al-Maklatí; and that of Syracuse under Ibn Thumna, while al-Samsam retained control of Palermo longer, before it adopted self-rule under a council of sheikhs. There followed a period of squabbles among the qadits that likely represented kin-groups jockeying for power. Ibn Thumna killed Ibn al-Maklatí, took Catania and married the dead qadi's widow who was the sister of Ibn al-Hawwàs. He also took ibn Mankut's qadit, but when his wife was prevented from returning from a visit to her brother, the Fatimid-allied Ibn Thumna attacked Ibn al-Hawwàs only to be defeated. When he left Sicily to recruit more troops, this briefly left Ibn al-Hawwàs in control of most of the island.[27] In waging his war on his rivals, Ibn Thumna had collaborated closely with the Normans, each using the other to further their goal of ruling the entire island, and though Ibn Thumna's death in a 1062 ambush led the Normans to draw back and consolidate, Ibn Thumna's former allies appear to have continued the alliance, such that Muslim troops constituted the majority of the Hauteville "Norman" army in Sicily.[28]

The Zirids of North Africa sent an army to Sicily led by Ali and Ayyub ibn Tamin, and these troops progressively brought the qadits under their control, killing al-Hawwàs and effectively making Ayyub emir of Muslim Sicily. However, they lost two decisive battles against the Normans. The Sicilians and North Africans were defeated in 1063 by a small Norman force at the Battle of Cerami, cementing Norman control over the north-east of the island. The sizeable Christian population rose up against the ruling Muslims. Then in 1068, Roger and his men defeated Ayyub at the Battle of Misilmeri, and the Zirids returned to North Africa, leaving Sicily in disarray. Catania fell to the Normans in 1071. Palermo, ruled since the Zirid withdrawal by Ibn al-Ba'ba, a man apparently of Spanish Jewish descent from the city's merchant class who led the city with the support of its sheikhs, would in turn fall on 10 January 1072 after a five month siege.[29][30] Trapani capitulated the same year.

The loss of the main port cities dealt a severe blow to Muslim power on the island. The last pocket of active resistance was Syracuse governed by Ibn Abbad (known as Benavert in western chronicles). He defeated Jordan, son of Roger of Sicily in 1075, and occupied Catania again in 1081 and raided Calabria shortly after. However, Roger besieged Syracuse in 1086, and Ibn Abbad tried to break the siege with naval battle, in which he died accidentally. Syracuse surrendered after this defeat. His wife and son fled to Noto and Butera. Meanwhile, the city of Qas'r Ianni (Castrogiovanni, modern Enna) was ruled by a Hammud, who surrendered and converted to Christianity only in 1087. After his conversion, Hammud subsequently became part of the Christian nobility and retired with his family to an estate in Calabria provided by Roger I. In 1091, Butera and Noto in the southern tip of Sicily and the island of Malta, the last Arab strongholds, fell to the Christians with ease. After the conquest of Sicily, the Normans removed the local emir, Yusuf Ibn Abdallah from power, while respecting the customs of the resident Arabs.[31]

Aftermath[edit]

The Norman Kingdom of Sicily under Roger II has been characterized as "multi-ethnic in nature and religiously tolerant". Normans, Jews, Muslim Arabs, Byzantine Greeks, Lombards and native Sicilians lived in relative harmony.[32][33] Arabic remained a language of government and administration for at least a century into Norman rule, and traces remain in the language of Sicily and evidently more in the language of Malta today.[12] The Muslims also maintained their domination of industry, retailing and production, while Muslim artisans and expert knowledge in government and administration were highly sought after.[34]

However, the island's Muslims were faced with the choice of voluntary departure or subjection to Christian rule. Many Muslims chose to leave, provided they had the means to do so. "The transformation of Sicily into a Christian island", remarks Abulafia, "was also, paradoxically, the work of those whose culture was under threat".[35][36] Also, Muslims gradually converted to Christianity, the Normans replaced Orthodox clergy with Latin clerics. Despite the presence of an Arab-speaking Christian population, Greek churchmen attracted Muslim peasants to receive a baptism and even adopted Greek Christian names; in several instances, Christian serfs with Greek names listed in the Monreale registers had living Muslim parents.[37][38] The Norman rulers followed a policy of steady Latinization by bringing in thousands of Italian settlers from the northwest and south of Italy, and some others from southeast France. To this day, there are communities in central Sicily which speak the Gallo-Italic dialect. Some Muslims chose to feign conversion, but such a remedy could only provide individual protection and could not sustain a community.[39]

"Lombard" pogroms against Muslims started in the 1160s. Muslim and Christian communities in Sicily became increasingly geographically separated. The island's Muslim communities were mainly isolated beyond an internal frontier which divided the south and western half of the island from the Christian north and eastern half. Sicilian Muslims, a subject population, were dependent on the mercy of their Christian masters and, ultimately, on royal protection. After King William the Good died in 1189 royal protection was lifted, and the door was opened for widespread attacks against the island's Muslims. This destroyed any lingering hope of coexistence, however unequal the respective populations might have been. The death of Henry VI and his wife Constance a year later plunged Sicily into political turmoil. With the loss of royal protection and with Frederick II still an infant in papal custody Sicily became a battleground for rival German and papal forces. The island's Muslim rebels sided with German warlords like Markward von Anweiler. In response, Innocent III declared a crusade against Markward, alleging that he had made an unholy alliance with the Saracens of Sicily. Nevertheless, in 1206 that same pope attempted to convince the Muslim leaders to remain loyal.[40] By this time the Muslim rebellion was in full swing. They were in control of Jato, Entella, Platani, Celso, Calatrasi, Corleone (taken in 1208), Guastanella and Cinisi. Muslim revolt extended throughout a whole stretch of western Sicily. The rebels were led by Muhammad Ibn Abbād. He called himself the "prince of believers", struck his own coins, and attempted to find Muslim support from other parts of the Muslim world.[41][42]

However, Frederick II, no longer a child, responded by launching a series of campaigns against the Muslim rebels in 1221. The Hohenstaufen forces rooted out the defenders of Jato, Entella, and the other fortresses. Rather than exterminate the Muslims who numbered about 60,000. In 1223, Frederick II and the Christians began the first deportations of Muslims to Lucera in Apulia.[43] A year later, expeditions were sent against Malta and Djerba, to establish royal control and prevent their Muslim populations from helping the rebels.[41] Paradoxically, in this era the Saracen archers were a common component of these "Christian" armies and the presence of Muslim contingents in the imperial army remained a reality even under Manfred and Conradin.[44]

The House of Hohenstaufen and their successors (Capetian House of Anjou and Aragonese House of Barcelona) gradually "Latinized" Sicily over the course of two centuries, and this social process laid the groundwork for the introduction of Latin (as opposed to Byzantine) Catholicism. The process of Latinization was fostered largely by the Roman Church and its liturgy. The annihilation of Islam in Sicily was completed by the late 1240s, when the final deportations to Lucera took place.[45] By the time of the Sicilian Vespers in 1282 there were no Muslims in Sicily and the society was completely Latinized.

List of emirs[edit]

- al-Hasan al-Kalbi (948–953)

- Ahmad ibn al-Hasan al-Kalbi (954–969)

- Ya'ish (969–970), usurper

- Abu'l-Qasim Ali ibn al-Hasan al-Kalbi (970–982)

- Jabir al-Kalbi (982–983)

- Ja'far al-Kalbi (983–985)

- Abdallah al-Kalbi (985–990)

- Yusuf al-Kalbi (990–998)

- Ja'far al-Kalbi (998–1019)

- al-Akhal (1019–1037)

- Abdallah (1037–1040), Zirid usurper

- Hasan as-Samsam (1040–1053)

Taifa period[edit]

- Abdallah ibn Mankut – Trapani and Mazara (1053–?)

- Ibn al-Maklatí – Catania (1053–?)

- Muhammed ibn Ibrahim (Ibn Thumna) – Syracuse (1053–1062) and in later years Catania and Trapani/Mazara

- Alí ibn Nima (Ibn al-Hawwàs) – Agrigento and Castrogiovanni (1053–about 1065), all Taifas from 1062

- Ayyub ibn Tamim (Zirid) (about 1065–1068)

- Ibn al-Ba'ba, Palermo (1068–1072)

- Hammad – Agrigento and Castrogiovanni (1068–1087)

- Ibn Abbad (Benavert) – Syracuse and Catania (1071–1086)

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Jewish Badge". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

- ^ a b c d e f "Brief history of Sicily" (PDF). Archaeology.Stanford.edu. 7 October 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 9, 2007.

- ^ Of Italy, Touring Club (2005). Authentic Sicily. Touring Editore. ISBN 978-88-365-3403-6.

- ^ Alex Metcalfe (2009). The Muslims of Medieval Italy (illustrated ed.). Edinburgh University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-7486-2008-1.

- ^ Michele Amari (1854). Storia dei musulmani di Sicilia. F. Le Monnier. p. 302 Vol III.

- ^ Roberto Tottoli (19 Sep 2014). Routledge Handbook of Islam in the West. Routledge. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-317-74402-3.

- ^ Graham A. Loud; Alex Metcalfe (1 Jan 2002). The Society of Norman Italy (illustrated ed.). BRILL. p. 289. ISBN 978-90-04-12541-4.

- ^ Jeremy Johns (7 Oct 2002). Arabic Administration in Norman Sicily: The Royal Diwan. Cambridge University Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-1-139-44019-6.

- ^ Metcalfe (2009), pp. 34–36, 40

- ^ Loud, G. A. (2007). The Latin Church in Norman Italy. Cambridge University Press. p. 494. ISBN 978-0-521-25551-6.

At the end of the twelfth century ... While in Apulia Greeks were in a majority–and indeed present in any numbers at all–only in the Salento peninsula in the extreme south, at the time of the conquest they had an overwhelming preponderance in Lucaina and central and southern Calabria, as well as comprising anything up to a third of the population of Sicily, concentrated especially in the north-east of the island, the Val Demone.

- ^ Davis-Secord, Sarah (2017-12-31). Where Three Worlds Met. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501712593. ISBN 978-1-5017-1259-3.

- ^ a b Smith, Denis Mack (1968). A History of Sicily: Medieval Sicily 800—1713. Chatto & Windus, London. ISBN 0-7011-1347-2.

- ^ Previte-Orton (1971), vol. 1, pg. 370

- ^ Islam in Sicily Archived 2011-07-14 at the Wayback Machine, by Alwi Alatas

- ^ Brian A. Catlos (26 Aug 2014). Infidel Kings and Unholy Warriors: Faith, Power, and Violence in the Age of Crusade and Jihad (illustrated ed.). Macmillan. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-374-71205-1.

- ^ Commissione mista per la storia e la cultura degli ebrei in Italia (1995). Italia judaica, Volume 5. Ufficio centrale per i beni archivistici, Divisione studi e pubblicazioni. p. 145. ISBN 978-88-7125-102-8.

- ^ Jonathan M. Bloom (2007). Arts of the City Victorious: Islamic Art and Architecture in Fatimid North Africa and Egypt (illustrated ed.). Yale University Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-300-13542-8.

- ^ Stefan Goodwin (1 Jan 1955). Africa in Europe: Antiquity into the Age of Global Exploration. Lexington Books. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-7391-2994-4.

- ^ Luscombe, David; Riley-Smith, Jonathan, eds. (2004). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge University Press. p. 696. ISBN 978-0-521-41411-1.

- ^ Marshall W. Baldwin; Kenneth Meyer Setton (2016). A History of the Crusades, Volume 1 The First Hundred Years. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-1-5128-1864-2.

- ^ E. Buringh (2011). Medieval Manuscript Production in the Latin West: Explorations with a Global Database. Brill. p. 73. ISBN 978-90-04-17519-8.

- ^ J. Bradford De Long and Andrei Shleifer (October 1993), "Princes and Merchants: European City Growth before the Industrial Revolution", The Journal of Law and Economics, 36 (2), University of Chicago Press: 671–702 [678], CiteSeerX 10.1.1.164.4092, doi:10.1086/467294, S2CID 13961320

- ^ a b Privitera, Joseph (2002). Sicily: An Illustrated History. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-7818-0909-2.

- ^ Mendola, Louis; Alio, Jacqueline (2014). The Peoples of Sicily: A Multicultural Legacy. Trinacria Editions. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-6157-9694-9.

Until the arrival of the Arabs, the most widely spoken language in Sicily was a medieval dialect of Greek. Under the Arabs, Sicily became a polyglot community; some localities were more Greek-speaking while others were predominantly Arabic-speaking." pages 141-142 "Mosques were constructed, often with the help of Byzantine craftsmen, and in Sicily the Church, formally under the Patriarchate of Constantinople from 732, remained solidly Greek Orthodox into the early years of Norman rule, when the beginnings of Latinization took place.

- ^ Archived link: From Islam to Christianity: the Case of Sicily, Charles Dalli, page 153. In Religion, ritual and mythology : aspects of identity formation in Europe / edited by Joaquim Carvalho, 2006, ISBN 88-8492-404-9.

- ^ Costantino, Alberto (2021-04-05). "Gli arabi in Sicilia / Alberto Costantino". opac.sbn.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2021-04-12.

- ^ Alex Metcalf, The Muslims of Medieval Italy, Edinburgh:Edinburgh University Press, 2009, pp. 84-85

- ^ Metcalf, The Muslims of Medieval Italy, pp. 94-95

- ^ Metcalf, The Muslims of Medieval Italy, pp. 97-98

- ^ Rogers, Randall (1997). Latin Siege Warfare in the Twelfth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-19-159181-5.

- ^ "Chronological - Historical Table Of Sicily". In Italy Magazine. 7 October 2007. Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ Roger II - Encyclopædia Britannica Archived 2007-05-23 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Inturrisi, Louis (April 26, 1987). "Tracing the Norman Rulers of Sicily". The New York Times.

- ^ Badawi, El-Said M.; Elgibali, Alaa, eds. (1996). Understanding Arabic: Essays in Contemporary Arabic Linguistics in Honor of El-Said Badawi. American Univ in Cairo Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-977-424-372-1.

- ^ Charles Dalli, From Islam to Christianity: the Case of Sicily, p. 159 (archived link)

- ^ Abulafia, The end of Muslim Sicily cit., p. 109

- ^ Charles Dalli, From Islam to Christianity: the Case of Sicily, p. 159 (archived link)

- ^ J. Johns, The Greek church and the conversion of Muslims in Norman Sicily?, "Byzantinische Forschungen", 21, 1995; for Greek Christianity in Sicily see also V. von Falkenhausen, "Il monachesimo greco in Sicilia", in C.D. Fonseca (ed.), La Sicilia rupestre nel contesto delle civiltà mediterranee, vol. 1, Lecce 1986.

- ^ Charles Dalli, From Islam to Christianity: the Case of Sicily, p. 160 (archived link)

- ^ Charles Dalli, From Islam to Christianity: the Case of Sicily, p. 160-161 (archived link)

- ^ a b Charles Dalli, From Islam to Christianity: the Case of Sicily, p. 161 (archived link)

- ^ Aubé, Pierre (2001). Roger Ii De Sicile - Un Normand En Méditerranée. Payot.

- ^ A.Lowe: The Barrier and the bridge, op cit;p.92.

- ^ "Saracen Archers in Southern Italy". 2007-11-28. Archived from the original on 2007-11-28. Retrieved 2021-04-12.

- ^ Abulafia, David (1988). Frederick II: A Medieval Emperor. London: Allen Lane.

Sources[edit]

- Previte-Orton, C. W. (1971). The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Emirate of Sicily

- 1091 disestablishments in Europe

- 11th-century disestablishments in Italy

- States and territories established in the 830s

- Shia dynasties

- Spread of Islam

- Former Islamic monarchies in Europe

- Former emirates

- Former Arab states

- Arab–Byzantine wars

- History of Malta

- 831 establishments

- 9th-century establishments in Italy