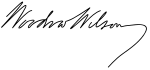

Foreign policy of the Woodrow Wilson administration

The foreign policy under the presidency of Woodrow Wilson deals with American diplomacy, and political, economic, military, and cultural relationships with the rest of the world from 1913 to 1921. Although Wilson had no experience in foreign policy, he made all the major decisions, usually with the top advisor Edward M. House. His foreign policy was based on his messianic philosophical belief that America had the utmost obligation to spread its principles while reflecting the 'truisms' of American thought.[1]

Wilson executed the Democratic Party foreign policy which since 1900 had, according to Arthur S. Link:

consistently condemned militarism, imperialism, and interventionism in foreign policy. They instead advocated world involvement along liberal-internationalist lines. Wilson's appointment of William Jennings Bryan as Secretary of State indicated a new departure, for Bryan had long been the leading opponent of imperialism and militarism and a pioneer in the world peace movement.[2]

The main foreign policy issues Wilson faced were civil war in neighboring Mexico; keeping out of World War I and protecting American neutral rights; deciding to enter and fight in 1917; and reorganizing world affairs with peace treaties and a League of Nations in 1919. Wilson had a physical collapse in late 1919 that left him too handicapped to closely supervise foreign or domestic policy.

Leadership[edit]

For advice and trouble shooting in foreign policy Wilson relied heavily on his trusted friend "Colonel" Edward M. House. Wilson came to distrust House's independence in 1919, and ended all contact.[3] After winning the presidency in the 1912 election, Wilson had no alternative choice for the premier cabinet position of Secretary of State. William Jennings Bryan had long been the dominant leader of the Democratic Party and had been essential to Wilson's presidential nomination. Nevertheless, the president-elect was worried about Bryan's radical reputation, and especially about his independent base.[4][5] Bryan had travelled the world giving speeches, promoting peace, and meeting with world leaders. Wilson had no such experience; he had studied English constitutional history in depth, but not its diplomatic history. He had not travelled widely outside the U.S. and Britain. Bryan proved very useful in helping pass major progressive domestic reforms through Congress, especially the Federal Reserve law. In foreign policy they worked together well at first. Bryan handled routine work and Wilson made the major decisions. Since Bryan had such a strong base in the Democratic Party, Wilson kept him informed, and allowed Bryan to pursue his own peace-priority of drafting 30 treaties with other countries that required both signatories to submit all disputes to an investigative tribunal. However he and Wilson clashed over U.S. neutrality in wartime. Bryan resigned in June 1915 after Wilson sent to Berlin a note of protest in response to the Sinking of the RMS Lusitania, a British passenger liner, by a German U-boat, with the death of 128 Americans. Bryan thought they travelled at their own risk into a war zone, while Wilson considered it was a violation of the laws of war to sink a passenger ship without giving the passengers a chance to reach the lifeboats.[6]

Wilson selected Robert Lansing to replace Bryan because he was proficient in routine work and passive in ideas and initiative. Unlike Bryan he lacked a political base. The result was that Wilson could be—and indeed actually was—freer to personally make all major foreign policy decisions. John Milton Cooper concludes that it was one of Wilson's worst mistakes as president.[7] Wilson told Colonel House that as president he would practically be his own Secretary of State, and "Lansing would not be troublesome by uprooting or injecting his own views."[8]

Lansing advocated "benevolent neutrality" at the start of the war, but shifted away from the ideal after increasing interference and violation of the rights of neutrals by Great Britain.[9] According to Lester H. Woolsey, a top aide in the State Department and later Lansing's law partner, Lansing by mid-1915 had very strong views against Germany. He kept these to himself because Wilson disagreed. Lansing expressed his views by manipulating the work of the State Department to minimize conflict with Britain and maximize public awareness of Germany's faults. Woolsey states:

Although the President cherished the hope that the United States would not be drawn into the war, and while this was the belief of many officials, Mr. Lansing early in July, 1915, came to the conclusion that the German ambition for world domination was the real menace of the war, particularly to democratic institutions. In order to block this German ambition, he believed that the progress of the war would eventually disclose to the American people the purposes of the German Government; that German activities in the United States and in Latin America should be carefully investigated and frustrated; that the American republics to the south should be weaned from the German influences; that friendly relations with Mexico should be maintained even to the extent of recognizing the Carranza faction; that the Danish West Indies should be acquired in order to remove the possibility of Germany's obtaining a foothold in the Caribbean by conquest of Denmark or otherwise; that the United States should enter the war if it should appear that Germany would become the victor; and that American public opinion must be awakened in preparation for this contingency. This outline of Mr. Lansing's views explains why the Lusitania dispute was not brought to the point of a break. It also explains why, though Americans were incensed at the British interference with commerce, the controversy was kept within the arena of debate.[10]

The two key Allied ambassadors were Cecil Spring Rice for Britain and Jean Jules Jusserand for France. The latter was highly successful, achieving popularity with Americans from many backgrounds and perspectives.[11] However Spring-Rice was a close friend of Wilson's enemies Theodore Roosevelt and Henry Cabot Lodge, and never was comfortable in the Wilsonian milieu. Wilson distrusted Spring-Rice as incompetent and a mischief-maker. House solved the problem by a close friendship with Sir William Wiseman, a British banker who took charge of financial negotiations as well as intelligence operations.[12] Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff was the German ambassador—suave and sophisticated. He tried and failed to get Berlin to accept Wilson's proposals for peace plans. Meanwhile, he was organizing propaganda activities. However, after the war he denied any involvement with sabotage activities to disrupt the shipment of American supplies to the Allies, such as the monster Black Tom explosion in 1916.[13][14][15]

Latin America[edit]

The Panama Canal opened in 1914, just after the start of World War 1. It fulfilled the long-term dream of building a canal across Central America and making possible quick movement between the Atlantic and the Pacific.. For the US Navy the canal allowed quick movement of fleets between the Pacific and the Atlantic. Economically it opened new opportunities to the shippers to reach the Far East. Britain insisted that treaty agreements meant its ships would pay the same toll as American ships, and Congress agreed to the same tolls for every nation.[16]

To further protect the Canal, in 1917, the US purchased the strategically located Danish West Indies for $25 million, in gold, from Denmark. The territory was renamed the United States Virgin Islands. Its population of 27,000 was over 90 per cent Black; its economy was based on sugar.[17]

Mexico[edit]

Washington had long recognized the dictatorial government of Porfirio Díaz. As Díaz approached eighty years old, he announced he was not going to run in the scheduled 1910 elections. This set off a flurry of political activity about presidential succession. Washington wanted any new president to continue Díaz's policies that had been favorable to American mining and oil interests and produced stability domestically and internationally. However Díaz suddenly reneged on his promise not to run, exiled General Bernardo Reyes, the most viable candidate. He had the most popular opposition candidate, Francisco I. Madero jailed. After the rigged 1910 reelection of Diaz, political unrest became open rebellion.[18]

After his Federal Army failed to suppress the insurgents, Díaz resigned and went into exile. An interim government was installed, and new elections were held in October 1911. These were won by Madero. Initially, Washington was optimistic about Madero. He had disbanded the rebel forces that had forced Díaz to resign; retain the Federal Army; and appeared to be open to friendly policies. However the U.S. began to sour on the relationship with Madero and began actively working with opponents to the regime. The new president Victoriano Huerta won recognition from all major countries except the U.S. Wilson, who took office shortly after Madero's assassination, rejected the legitimacy of Huerta's "government of butchers" and demanded that Mexico hold democratic elections to replace him.[19] In the Tampico Affair of April 9, 1914 nine American sailors were seized for about an hour by Huerta's soldiers. The local commander apologized and released the sailors but refused the demand of the American admiral to salute the U.S. flag and punish the arrested officer. The conflict escalated with Washington's approval and the U.S. Navy seized Veracruz. Some 170 Mexican soldiers and an unknown number of Mexican civilians were killed in the takeover, as well as 22 Americans.[20]

Pancho Villa (1878–1923), a local bandit who built up a regional base, became a major national figure when he led anti-Huerta forces in the Constitutionalist Army 1913–14. At the height of his power and popularity in late 1914 and early 1915, Washington considered recognizing him as Mexico's legitimate authority. However Villa was decisively defeated by Constitutionalist General Alvaro Obregón in summer 1915, and the U.S. aided Constitutionalist leader Venustiano Carranza directly against Villa. Villa, much weakened, conducted a raid on the small border village of Columbus, New Mexico killing 18 Americans. His goal was to goad Wilson into a war with Carranza.[21] Instead Wilson sent the Army on a limited punitive expedition led by General John J. Pershing deep into Mexico. It failed to capture Villa.[22] Mexican public and elite opinion turned strongly against the U.S. and war was growing more and more likely. Wilson realized that escalating tensions with Germany were much more important and recalled the invasion force in early 1917 as war with Germany approached.[23]

Meanwhile, Germany was trying to divert American attention from Europe by sparking a war. It sent Mexico the Zimmermann Telegram in January 1917, offering a military alliance to reclaim lands the United States had forcibly taken via conquest in the Mexican–American War. British intelligence intercepted the message, and revealed it to the American government when tensions were high. Wilson released it to the press, escalating demands for American war against Germany. The Mexican government rejected the proposal after its military warned of massive defeat if they attempted to follow through with the plan. Mexico stayed neutral; selling large amounts of oil to Britain for the Royal Navy.[24]

Nicaragua[edit]

According to Benjamin Harrison, Wilson was committed in Latin America to the fostering of democracy and stable governments, as well as fair economic policies.[25] Wilson was largely frustrated by the chaotic situation in Nicaragua. Adolfo Díaz won the presidency in 1911 and replaced European financing with loans from New York banks. Facing a Liberal rebellion, he called on the United States for protection and Wilson obliged. Nicaragua assumed a quasi-protectorate status under the 1916 Bryan–Chamorro Treaty. Under the treaty Nicaragua promised it would not declare war on anyone, would not grant territorial concessions, and would not contract outside debts without Washington's approval. It permitted the US to build a naval base at Fonseca Bay, and gave the US the sole option to construct and control an inter-oceanic canal. The US had no intention of building a canal, but one of the guarantee that no other nation could do so. The US paid Nicaragua $3 million for this option. The original draft also asserted the duty of the United States to intervene militarily in case of domestic turmoil – but that provision was rejected by Democrats in the Senate.[26][27] The treaty was extremely unpopular in the Caribbean region, but it was observed by both sides until 1933. Díaz was now able to serve out his entire term; he retired in 1917, and moved to the United States, though he briefly returned to power in 1926–1929. According to George Baker, the main effect of the treaty was a higher degree of both political and financial stability in Nicaragua.[28] President Herbert Hoover (1929-1933) opposed the relationship. Finally in 1933, President Franklin D Roosevelt invoked his new Good Neighbor policy to end American intervention.[29]

Asia[edit]

China[edit]

After the Xinhai Revolution overthrew the emperor in 1911, The Taft administration recognized the new Government of the Chinese Republic as the legitimate government of China. In practice a number of powerful regional warlords were in control and the central government handled foreign policy and little else.

The Twenty-One Demands were a set of secret demands made in 1915 by Japan to Yuan Shikai the general who served as president of the Republic of China The demands would greatly extend Japanese control. Japan would keep the former German concessions it had conquered at the start of World War I in 1914. Japan would be stronger in Manchuria and South Mongolia. It would have an expanded role in railways. The most extreme demands—the fifth set—would gave Japan a decisive voice in China's finance, policing, and government affairs. Indeed, they would make China in effect a protectorate of Japan, and thereby reduce Western influence. Japan was in a strong position, as the Western powers were in a stalemated war with Germany. Britain and Japan had a military alliance since 1902, and in 1914 London had asked Tokyo to enter the war. Beijing published the secret demands and appealed to Washington and London. They were sympathetic and pressured Tokyo. In the final 1916 settlement, Japan gave up its fifth set of demands. It gained a little in China, but lost a great deal of prestige in Washington and London.[30] E. T. Williams, the senior expert on the Far East in the State Department, argued in January 1915:

- Our present commercial interests in Japan are greater than those in China, but the look ahead shows our interest to be a strong and independent China rather than one held in subjection by Japan. China has certain claims upon our sympathy. If we do not recognize them...we are in danger of losing our influence in the Far East and of adding to the dangers of the situation.[31]

Wilson has been criticized for accepting at the Paris Peace Conference the transfer of the German concession in Shandong to Japan, instead of allowing China to reclaim it.[32] However Bruce Elleman has argued that Wilson did not betray China because his action was in accord with widely recognized treaties which China had signed with Japan during the war. Wilson tried to get Japan to promise to return the concessions in 1922, but the Chinese delegation rejected that compromise. The result in China was the growth of intense nationalism characterized by the May Fourth Movement, and the tendency of intellectuals and activists in the 1920s to look to Moscow for leadership.[33][30]

Wilson was in touch with several former Princeton students who were missionaries in China, and he strongly endorsed their work. In 1916 he told a delegation of ministers:

This is the most amazing and inspiring vision - this vision of that great sleeping nation suddenly awakened by the voice of Christ. Could there be any greater contribution to the future momentum of the moral forces of the world than could be made by quickening the force, which is being set of foot in China? China is at present inchoate; as a nation it is a congeries of parts, in each of which there is energy, but which are unbound in any essential and active unit, and just as soon as unity comes, its power will come in the world.[34]

Japan[edit]

In 1913, California enacted the California Alien Land Law of 1913 to exclude resident Japanese non-citizens from owning any land in the state. Tokyo protested strongly, and Wilson sent Bryan to California to mediate. Bryan was unable to get California to relax the restrictions, and Wilson accepted the law even though it violated a 1911 treaty with Japan. The law bred resentment in Japan which lingered into the 1920s and 1930s.[35][36]

During World War I, both nations fought on the Allied side. With the cooperation of its ally Great Britain, Japan's military took control of German bases in China and the Pacific, and in 1919 after the war, with U.S. approval, was given a League of Nations mandate over the German islands north of the equator, with Australia getting the rest. The U.S. did not want any mandates.[37]

Japan's aggressive approach in its dealings with China, however, was a continual source of tension—indeed eventually leading to World War II between the two nations. Trouble arose between Japan on the one hand and China, Britain and the U.S. on the other over Japan's Twenty-One Demands made on China in 1915. These demands forced China to acknowledge Japanese possession of the former German holdings and its economic dominance of Manchuria, and had the potential of turning China into a puppet state. Washington expressed strongly negative reactions to Japan's rejection of the Open Door Policy. In the Bryan Note issued by Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan on March 13, 1915, the U.S., while affirming Japan's "special interests" in Manchuria, Mongolia and Shandong, expressed concern over further encroachments to Chinese sovereignty.[38]

In 1917 the Lansing–Ishii Agreement was negotiated. Secretary of State Robert Lansing specified American acceptance that Manchuria was under Japanese control, while still nominally under Chinese sovereignty. Japanese Foreign Minister Ishii Kikujiro noted Japanese agreement not to limit American commercial opportunities elsewhere in China. The agreement also stated that neither would take advantage of the war in Europe to seek additional rights and privileges in Asia.[39]

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Japan insisted that Germany's concessions in China, especially in the Shandong Peninsula, be transferred to Japan. President Woodrow Wilson fought vigorously against Japan's demands regarding China, but backed down upon realizing the Japanese delegation had widespread support.[40] In China there was outrage and anti-Japanese sentiment escalated. The May Fourth Movement emerged as a student demand for China's honor.[41] In 1922 the U.S. brokered a solution of the Shandong Problem. China was awarded nominal sovereignty over all of Shandong, including the former German holdings, while in practice Japan's economic dominance continued.[42]

Philippines[edit]

The Democratic party in the United States had strongly opposed acquisitions of the Philippines in the first place, and increasingly became committed to independence. Wilson himself was a conservative in the 1890s and supported McKinley's foreign policy and favored annexation of the Philippines.[43] The election of a Democratic president and Congress in 1912 opened up opportunities and Wilson had changed. He now wanted the islands to be governed by Filipinos until it became independent.[44] He appointed Francis Burton Harrison as governor, and Harrison replaced nearly all the mainlanders with Filipinos in the bureaucracy. By 1921, of the 13,757 bureaucrats, 13,143 were Filipinos; they held 56 of the top 69 positions.[45]

Philippine nationalists led by Manuel L. Quezon and Sergio Osmeña enthusiastically endorsed the draft Jones Bill of 1912, which provided for Philippine independence after eight years, but later changed their views, opting for a bill which focused less on time than on the conditions of independence. The nationalists demanded complete and absolute independence to be guaranteed by the United States, since they feared that too-rapid independence from American rule without such guarantees might cause the Philippines to fall into Japanese hands. The Jones Bill was rewritten and passed a Congress controlled by Democrats in 1916 with a later date of independence.[46]

The Jones Law, or Philippine Autonomy Act, replaced the Organic Act as the constitution for the territory. Its preamble stated that the eventual independence of the Philippines would be American policy, subject to the establishment of a stable government. The law maintained an appointed governor-general, but established a bicameral Philippine Legislature and replaced the appointive Philippine Commission with an elected senate.[47]

Filipino activists suspended the independence campaign during the World War and supported the United States and the Allies of World War I against the German Empire. After the war they resumed their independence drive with great vigour.[48] In 1919, the Philippine Legislature passed a "Declaration of Purposes", which stated the inflexible desire of the Filipino people to be free and sovereign. A Commission of Independence was created to study ways and means of attaining liberation ideal. This commission recommended the sending of an independence mission to the United States. The "Declaration of Purposes" referred to the Jones Law as a veritable pact, or covenant, between the American and Filipino peoples whereby the United States promised to recognize the independence of the Philippines as soon as a stable government should be established. American Governor-General Harrison had concurred in the report of the Philippine Legislature as to a stable government.[49][50]

Russia and its Revolution[edit]

President Wilson believed that with the end of Tsarist rule the new country would eventually transition to a modern democracy after the end of the chaos of the Russian Civil War, and that intervention against Soviet Russia would only turn the country against the United States. He likewise publicly advocated a policy of noninterference in the war in the Fourteen Points, although he argued that the Russia's prewar Polish territory should be ceded to the newly independent Second Polish Republic. Additionally many of Wilson's political opponents in the United States, including the Chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee Henry Cabot Lodge, believed that an independent Ukraine should be established. Despite this the United States, as a result of the fear of Japanese expansion into Russian-held territory and their support for the Allied-aligned Czech Legion, sent a small number of troops to Northern Russia and Siberia. The United States also provided indirect aid such as food and supplies to the White Army.[51][52]

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 Wilson and British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, despite the objections of French President Georges Clemenceau and Italian Foreign Minister Sidney Sonnino, pushed forward an idea to convene a summit at Prinkipo between the Bolsheviks and the White movement to form a common Russian delegation to the Conference. The Soviet Commissariat of Foreign Affairs, under the leadership of Leon Trotsky and Georgy Chicherin, received British and American envoys respectfully but had no intentions of agreeing to the deal due to their belief that the Conference was composed of an old capitalist order that would be swept away in a world revolution. By 1921, after the Bolsheviks gained the upper hand in the Russian Civil War, executed the Romanov imperial family, repudiated the tsarist debt, and called for a world revolution by the working class, it was regarded as a pariah nation by most of the world.[52] Beyond the Russian Civil War, relations were also dogged by claims of American companies for compensation for the nationalized industries they had invested in.[53]

Famine and starvation raged in Russia and parts of Eastern Europe after the war. A very large food relief operation, centered mostly in Russia, was primarily funded by the U.S. government, as well as philanthropies, and Britain and France. The American Relief Administration, 1919–1923, at first was under the direction of Herbert Hoover.[54][55]

Wilson had been reluctant to join but he sent two forces into Russia. The American Expeditionary Force, Siberia was a formation of the United States Army involved in the Russian Civil War in Vladivostok, Russia, from 1918 to 1920. The other force was the American Expeditionary Force, North Russia a part of the larger Allied French and British North Russia Intervention, under the command of British General Edmund Ironside. The Siberian force was ostensibly designed to help the 40,000 men of the Czechoslovak Legion, who were being held up by Bolshevik forces as they attempted to make their way along the Trans-Siberian Railroad to Vladivostok, and it was hoped, eventually to the Western Front. They had escaped from Russian POW camps and were headed to join the Allies on the Western Front. The North Russia force had a mission of preventing the German army from seizing Allied munitions sent there before Russia dropped out of the war. Neither force had an officially acknowledged combat mission. Historians have speculated that Wilson shared the anti-Bolshevik ambitions of the larger Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War.[56][57]

Entry into World War I[edit]

Brokering peace[edit]

From the outbreak of the war in 1914 until January 1917, Wilson's primary goal was using American neutrality to broker a peace conference that would end the war. In the first two years neither side was interested in negotiations.[58] However, that changed in late 1916 when, Philip D. Zelikow argues, both sides were ready for peace negotiations, if Wilson would be the broker. However, Wilson waited too long, failed to realize the importance of his financial power over Britain, and put mistaken reliance on Colonel House and Secretary of State Robert Lansing, who undermined his proposals by encouraging Britain to stall. Zelikow emphasizes that German Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg was seriously interested in peace, but he had to fend off the demands of Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff who were taking dictatorial control of Germany. Zelikow argues that when Wilson finally did make his peace proposal in January 1917, it was too little and too late, and instead of peace the war escalated. Hindenburg and Ludendorff had convinced the Kaiser that victory was at hand by using unrestricted submarine warfare, and moving troops in from the Russian front to smash the French and British front lines.[59]

Wilson's decision to enter the war came in April 1917, more than two and a half years after the war began. The main reasons were the German submarine campaign to sink American ships carrying supplies to Britain, and his determination to make the world safe for democracy. Joseph Siracusa argues that Wilson's own position evolved from, 1914 to 1917. He finally decided that war was necessary because Germany threatened American global ideals of democracy and peace through militarism and Prussian autocracy. Furthermore, it was a threat to American commerce on the high seas, and to American rights as a neutral.[60] Public opinion, elite opinion, and Members of Congress gave Wilson strong support by April 1917. The U.S. took an independent role and did not have a formal alliance with Britain or France.

German submarine warfare against Britain[edit]

With the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, the United States declared neutrality and worked to broker a peace. It insisted on its neutral rights, which included allowing private corporations and banks to sell supplies or loan money to either side. With the tight British blockade, there were almost no sales or loans to Germany, only to the Allies. Americans were shocked by the Rape of Belgium—German Army atrocities against civilians in Belgium . Britain was favored by elite WASP element. Pro-war forces were led by ex-president Theodore Roosevelt, who repeatedly denounced Wilson for timidity and cowardice. Wilson insisted on neutrality, denouncing both British and German violations. The British seized American property; the Germans seized American lives. In 1915 a German U-boat (a kind of submarine) torpedoed the unarmed British passenger liner RMS Lusitania. It sank in 20 minutes, killing 128 American civilians and over 1,000 Britons. It was against the laws of war to sink any passenger ship without allowing the passengers to reach the life boats. American opinion turned strongly against Germany as a bloodthirsty threat to civilization.[61] Germany apologized and promised to stop attacks by its U-boats. Both sides rejected Wilson's repeated effors to negotiate an end to the war. Berlin reversed course in early 1917 when it saw the opportunity to strangle Britain's food supply by unrestricted submarine warfare. The Kaiser and Germany's real rulers, the Army commanders, realized it meant war with the United States, but expected they could defeat the Allies before the Americans could play a major military role. Germany started sinking American merchant ships in early 1917. Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war in April 1917. He neutralized the antiwar element by arguing this was a war with the main long-term postwar goal of ending aggressive militarism and making the world "safe for democracy."[62]

Public opinion[edit]

Apart from White Anglo-Saxon Protestant and Anglophile high society demanding a Special Relationship with the British Empire, American public opinion in 1914-1916 reflected a strong desire to stay out of the war. Support for American neutrality was particularly strong among those whom Wilson later demonised as Hyphenated Americans; Irish Americans, German Americans, and Scandinavian Americans, as well as among church leaders, women, and the rural white South.[63] Due in large part to the anti-German atrocity propaganda composed by British Intelligence at Wellington House and introduced into the American news media by Australian-born Providence Journal editor John R. Rathom, pro-Neutrality groups completely lost their broader influence. By early 1917 most Americans had come to believe that Imperial Germany was the aggressor in Europe and the enemy of world peace.[64]

Economic factors[edit]

While the country was at peace, American banks made huge loans to the Entente powers, which were used mainly to buy munitions, raw materials, and food from across the Atlantic. Although Wilson made minimal preparations for the army before 1917, he did authorize a massive shipbuilding program for the United States Navy. The president was narrowly re-elected in 1916 on an anti-war platform.

By 1917, with Belgium and Northern France occupied, with Russia ending Tsarist rule, and with the remaining Entente nations low on credit, Germany appeared to have the upper hand in Europe.[65] However, the British economic embargo and naval blockade was causing shortages of fuel and food in Germany, which then decided to resume unrestricted submarine warfare. The aim was to break the transatlantic supply chain to Britain from other nations, although the German high command realized that sinking American-flagged ships would almost certainly bring the United States into the war.

Germany's Zimmermann Telegram outraged Americans just as German submarines started sinking American merchant ships in the North Atlantic. Wilson asked Congress for "a war to end all wars" that would "make the world safe for democracy", and Congress voted to declare war on Germany on April 6, 1917.[66] The US immediately provided money and more supplies, and a small military force. American troops began major combat operations on the Western Front under General John J. Pershing in the summer of 1918, arriving at the rate of 10,000 soldiers a day.

Austria-Hungary and Ottoman Empire[edit]

The Senate, in a 74 to 0 vote, declared war on Austria-Hungary on December 7, 1917, citing Austria-Hungary's severing of diplomatic relations with the United States, its use of unrestricted submarine warfare and its alliance with Germany.[67] The declaration passed in the House by a vote of 365 to 1. The US never declared war on Germany's other allies the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria.[68]

The Paris Peace Conference and the Treaty of Versailles[edit]

The Paris Peace Conference convened in January 1919 in Paris, hosted by France. The conference was called to establish the terms of the peace after World War I. Though nearly thirty nations participated, the representatives of Great Britain, France, the United States, and Italy became known as the “Big Four.” Italy quit after losing itsa claim to Fiume, leaving the Big Three: Wilson, Prime Minister David Lloyd George and French premier Georges Clemenceau. They dominated the proceedings and drafted the Treaty of Versailles to end the war with Germany. The Treaty of Versailles articulated the compromises reached at the Paris conference. It included the planned formation of the League of Nations, which would serve both as an international forum and an international collective security arrangement. Wilson focused on the League, but fatally refused to work with the Republicans who controlled Congress. Clemenceau focused on permanently weakening Germany.[69] Lloyd George, sitting he said between Jesus Christ and Napoleon, tried to fashion compromises.[70]

According to Michael Neiberg:

Wilson received an ecstatic welcome from the people of Europe. At least for a little while, Europeans tired of war and conflict saw him as a potential savior from the old system and a possible architect of a newer, more just world. But that feeling did not last long. European leaders quickly came to dislike Wilson’s constant moralizing, his lack of understanding of the problems of Europe, and his stubborn unwillingness to see the destruction of France with his own eyes for fear, he said, of the devastation hardening his heart toward Germany. By the time the conference ended, almost everyone in Europe, and many members of the American delegation itself, had grown weary of Wilson and frustrated with his ineffectiveness at the conference.[71]

Treaty of Versailles[edit]

Negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference were complicated. Great Britain, France, and Italy fought together as the Allied Powers. The United States, entered the war in 1917 as an "Associated Power." While the U.S. fought alongside the Allies, it was not bound by treaty with any of them. Nor was it bound to honor pre-existing agreements among the Allied Powers. These secret agreements focused on postwar redistribution of territories. President Wilson strongly opposed many of these arrangements, including Italian demands on the Adriatic. This often led to significant disagreements among the "Big Four."[72] Wilson strongly opposed the Italian demand for control of Fiume, and had the support of Britain and France, whereupon the Italian delegation went home. However Colonel House had been supporting a compromise with the Italians, which alienated Wilson. Their close relationship slowly came to an end.[73][74]

Treaty negotiations were complicated by the absence of other important nations. The Allies excluded the defeated Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey, and Bulgaria). Russia had fought as one of the Allies until December 1917, when its new Bolshevik Government withdrew from the war. The Bolshevik decision to repudiate Russia's outstanding financial debts to the Allies and to publish the texts of secret agreements between the Allies angered the Allies. The Big Four refused to recognize the new government in Moscow and did not invite its representatives to the Peace Conference.[75][76]

According to French and British wishes, the Treaty of Versailles subjected Germany to strict punitive measures. The Treaty required the new German Government to surrender approximately 10 percent of its prewar territory in Europe and all of its colonies. It placed the harbor city of Danzig (now Gdansk) and the coal-rich Saarland under the administration of the League of Nations, and allowed France to exploit the economic resources of the Saarland until 1935. It limited the German Army and Navy in size, and allowed for the trial of Kaiser Wilhelm II and a number of other high-ranking German officials as war criminals. Under the terms of Article 231 of the Treaty, the Germans accepted responsibility for the war and the liability to pay financial reparations to the Allies. The Inter-Allied Commission determined the amount and presented its findings in 1921. The amount they determined was 132 billion gold Reichsmark, or 32 billion U.S. dollars, on top of the initial $5 billion payment demanded by the Treaty. Germans grew to resent the harsh conditions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles.[77]

Senate rejection[edit]

While the Treaty of Versailles did not satisfy all parties concerned, by the time President Woodrow Wilson returned to the United States in July 1919, U.S. public opinion probably favored ratification of the Treaty, including the Covenant of the League of Nations. With a two-thirds majority required for ratification, Senate voted on several versions but never ratified any.[78]

The opposition focused on Article 10 of the Treaty, which dealt with collective security and the League of Nations. This article, opponents argued, ceded the war powers of the U.S. Government to the League's Council. The opposition came from two groups: the “Irreconcilables,” who refused to join the League of Nations under any circumstances, and “Reservationists,” led by Senate Foreign Relations Committee Chairman, Henry Cabot Lodge, who wanted amendments made before they would ratify the Treaty. While Chairman Lodge's attempt to pass amendments to the Treaty was unsuccessful in September, he did manage to attach 14 “reservations” to it in November. In a final vote on March 19, 1920, the Treaty of Versailles fell short of ratification by seven votes. Consequently, the U.S. Government signed the Treaty of Berlin on August 25, 1921. This separate peace treaty with Germany stipulated that the United States would enjoy all “rights, privileges, indemnities, reparations or advantages” conferred to it by the Treaty of Versailles, but left out any mention of the League of Nations, which the United States never joined.[79]

Idealism, moralism and Wilsonianism[edit]

A Presbyterian of deep religious faith, Wilson appealed to a gospel of service and promoted a profound sense of moralism. Wilson's idealistic internationalism, now referred to as "Wilsonianism," calls for the United States to enter the world arena to fight for democracy, and has been a contentious position in American foreign policy, serving as a model for "idealists" to emulate and "realists" to reject ever since.[80][81]

Missionary diplomacy[edit]

Missionary diplomacy was Wilson's idea that Washington had a moral responsibility to deny diplomatic recognition to any Latin American government that was not democratic. It was an expansion of President James Monroe's 1823 Monroe Doctrine.[82][83]

Fourteen Points[edit]

The Fourteen Points was Wilson's statement of principles that was to be used for peace negotiations to end the war. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms to Congress by President Wilson. By October 1918, the new German government was negotiating with Wilson for peace based on the Fourteen Points.[84] However, his main Allied colleagues (Georges Clemenceau of France, and David Lloyd George of Great Britain) were skeptical of the applicability of Wilsonian idealism.[85] Wilson called for the abolition of secret treaties, a reduction in armaments, an adjustment in colonial claims in the interests of both native peoples and colonists, and freedom of the seas. Wilson also made proposals intended to ensure world peace in the future. For example, he proposed the removal of economic barriers between nations, and the promise of self-determination for national minorities. Most important of all, the Fourteenth Point, was a world organization that would guarantee the "political independence and territorial integrity [of] great and small states alike"—a League of Nations.[86] In his intense negotiations with Clemenceau and Lloyd George he was reluctantly willing to compromise on this point and that, but always insisted on keeping the League.[87]

Principles of Wilsonianism[edit]

The principles associated with "Wilsonianism" across the 20th century and into the 21st include:[88][89][90]

- Conferences and bodies devoted to resolving conflict, especially the League of Nations and the United Nations.[91]

- Advocacy of the spread of democracy.[92] Anne-Marie Slaughter writes that Wilson expected and hoped "that democracy would result from self-determination, but he never sought to spread democracy directly."[93] Slaughter writes that Wilson's League of Nations was similarly intended to foster democracy by serving as "a high wall behind which nations" (especially small nations) "could exercise their right of self determination" but that Wilson did not envision that the U.S. would affirmatively intervene to "direct" or "shape" democracies in foreign nations.[93]

- Emphasis on self-determination of peoples;[94]

- Advocacy of the spread of capitalism[95]

- Support for collective security, and at least partial opposition to American isolationism.[96]

- Support for multilateralism through collective deliberation among nations[93]

- Support for open diplomacy and opposition to secret treaties[96][97]

- Support for freedom of navigation and freedom of the seas[96][98]

Impact of Wilsonianism[edit]

American foreign relations since 1914 have rested on Wilsonian idealism, argues historian David Kennedy. "Wilson's ideas continue to dominate American foreign policy in the twenty-first century. In the aftermath of 9/11 they have, if anything, taken on even greater vitality."[99][100]

Wilson was a remarkably effective writer and thinker and his diplomatic policies had a profound influence on the world. Diplomatic historian Walter Russell Mead has explained:

Wilson's principles survived the eclipse of the Versailles system and that they still guide European politics today: self-determination, democratic government, collective security, international law, and a league of nations. Wilson may not have gotten everything he wanted at Versailles, and his treaty was never ratified by the Senate, but his vision and his diplomacy, for better or worse, set the tone for the twentieth century. France, Germany, Italy, and Britain may have sneered at Wilson, but every one of these powers today conducts its European policy along Wilsonian lines. What was once dismissed as visionary is now accepted as fundamental. This was no mean achievement, and no European statesman of the twentieth century has had as lasting, as benign, or as widespread an influence.[101]

Alternative interpretations[edit]

Historians and political analysts have been largely Wilsonian in their approach to American diplomatic history, according to Lloyd Ambrosius. However, there are two alternative schools of thought as well. Ambrosius argues that Wilsonianism is based on national self-determination and democracy; open door globalization based on open markets for trade and finance; collective security as typified by Wilson's idea of the League of Nations as well as NATO; and a hope bordering on a promise of future peace and progress.[102] Realism is the first alternative school, based on the outlook and policies of Theodore Roosevelt, and represented most famously by George Kennan, Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon. They blame Wilson for giving too much emphasis on Democracy—that for realists was a low priority—they would eagerly work with dictators who supported American positions. A third approach emerged from the New Left in the 1960s, led by William Appleman Williams and the "Wisconsin School". It is called "Revisionism" and argues that selfish economic motivations, not idealism or realism, motivated Wilsonianism. Ambrosius argues that historians generally agree that Wilsonianism was the main intellectual force in battling the Nazis in 1945 and the Soviet communists in 1989. It seemed to be the dominant factor in world affairs by 1989.[103] Wilsonians were shocked when the Chinese Communists rejected democracy in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, and when Putin rejected it for Russia.[104]

Wilsonians were dismayed when George W. Bush's initiative to bring democracy to the Middle East after 9/11 failed.[105] It produced not an Arab Spring, but instead antidemocratic results most famously in Egypt, Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan.[106][107]

See also[edit]

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- Economic history of World War I

- History of China–United States relations to 1948

- France–United States relations

- Germany–United States relations

- Japan–United States relations

- Latin America–United States relations

- Mexico–United States relations

- United Kingdom–United States relations

- Walter Hines Page, US ambassador

- United States in World War I

- Edward M. House, Colonel House was Wilson's main advisor

Notes[edit]

- ^ Kissinger, Henry (1994). Diplomacy. Simon & Schuster Paperbacks. p. 30.

- ^ William A. Link and Arthur S. Link, American Epoch: A History of the United States Since 1900. Vol. 1. War, Reform, and Society, 1900-1945 (7th ed, 1993) p 127.

- ^ Wilson's wife froze out House after the president became disabled. Charles E. Neu, Colonel House: A Biography of Woodrow Wilson's Silent Partner (2015) pp. 427, 432, 434.

- ^ Arthur S. Link, Wilson, Volume II: The New Freedom (1956) 2:7–9.

- ^ August Heckscher, Woodrow Wilson (1991) pp 269-270.

- ^ Ernest R. May, The World War and American Isolation, 1914-1917 (1959) pp 137–155.

- ^ John Milton Cooper, Woodrow Wilson: a biography (2009) p. 295

- ^ Arthur S. Link, Wilson: the struggle for neutrality 1914-1915 (1960) 3:427-428

- ^ See Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, The Lansing Papers, 1914–1920, Volume I, Document 277. In the enclosure it is stated that "If the British Government is expecting an attitude of “benevolent neutrality” on our part—a position which is not neutral and which is not governed by the principles of neutrality—they should know that nothing is further from our intention."

- ^ Lester H. Woolsey, "Robert Lansing's Record as Secretary of State." Current History 29.3 (1928): 386-387

- ^ Robert Young, An American by Degrees: The Extraordinary Lives of French Ambassador Jules Jusserand (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2009)

- ^ Neu, (2015) pp 148, 219, 309.

- ^ Link, Wilson 5:278–280.

- ^ Reinhard R. Doerries, Imperial Challenge: Ambassador Count Bernstorff and German-American Relations, 1908-1917 (1989)

- ^ Stephen Irving Max Schwab, "Sabotage at Black Tom Island: A wake-up call for America." International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence 25.2 (2012): 367-391.

- ^ William S. Coker, "The Panama Canal Tolls Controversy: A Different Perspective." Journal of American History 55.3 (1968): 555-564 online.

- ^ Leila Amos Pendleton, "Our New Possessions-The Danish West Indies." Journal of Negro History 2.3 (1917): 267-288. online

- ^ Karl M. Schmitt, Mexico and the United States, 1821-1973 (1974) pp 108–126.

- ^ Peter V. N. Henderson, "Woodrow Wilson, Victoriano Huerta, and the Recognition Issue in Mexico," The Americas (1984) 41#2 pp. 151–176 JSTOR 1007454

- ^ Jack Sweetman, The Landing at Veracruz: 1914 (Naval Institute Press, 1968).

- ^ Michael E. Neagle, "A Bandit Worth Hunting: Pancho Villa and America’s War on Terror in Mexico, 1916-1917." Terrorism and Political Violence 33.7 (2021): 1492-1510.

- ^ James W. Hurst, Pancho Villa and BlackJack Pershing: The Punitive Expedition in Mexico (2008).

- ^ James A. Sandos, "Pancho Villa and American Security: Woodrow Wilson's Mexican Diplomacy Reconsidered." Journal of Latin American Studies 13.2 (1981): 293-311.

- ^ Thomas Boghardt, The Zimmermann Telegram: Intelligence, Diplomacy, and America's Entry into World War I (Naval Institute Press, 2012).

- ^ Benjamin T Harrison, "Woodrow Wilson in Nicaragua," Caribbean Quarterly (2005) 51#1 pp 25-36.

- ^ Arthur S. Link, Wilson: The New Freedom (1956) pp. 331–342.

- ^ Arthur S. Link, ed., The Papers of Woodrow Wilson volume 27: 1913 (1978) pp 470, 526–530, 552

- ^ George W. Baker, Jr., "The Wilson Administration and Nicaragua,1913-1921," Americas (1966) 22#4 pp 339-376.

- ^ Alan McPherson, "Herbert Hoover, Occupation Withdrawal, and the Good Neighbor Policy." Presidential Studies Quarterly 44.4 (2014): 623-639. online[dead link]

- ^ a b Bruce Elleman, Wilson and China: A Revised History of the Shandong Question (Routledge, 2015).

- ^ Arthur S. Link, Wilson, Volume III: The Struggle for Neutrality, 1914-1915 (1960) pp 276, quoting E.T. Williams, head of the Far Eastern Division; italics in his memo to Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan.

- ^ Madeleine Chi, "China and Unequal Treaties at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919." Asian Profile 1.1 (1973): 49-61.

- ^ Bruce A. Elleman, "Did Woodrow Wilson really betray the Republic of China at Versailles?" American Asian Review (1995) 13#1 pp 1-28.

- ^ Eugene P. Trani, "Woodrow Wilson, China, and the Missionaries, 1913—1921." Journal of Presbyterian History 49.4 (1971): 328-351, quoting pp 332-333.

- ^ Herbert P. Le Pore, "Hiram Johnson, Woodrow Wilson, and the California Alien Land Law Controversy of 1913." Southern California Quarterly 61.1 (1979): 99–110. in JSTOR

- ^ Arthur Link, Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era (1954) pp. 84–87

- ^ Cathal J. Nolan, et al. Turbulence in the Pacific: Japanese-U.S. Relations during World War I (2000)

- ^ Walter LaFeber, The Clash: A History of U.S.-Japan Relations pp.106-116

- ^ J. Chal Vinson, "The Annulment of the Lansing-Ishii Agreement." Pacific Historical Review (1958): 57-69. Online

- ^ A. Whitney Griswold, The Far Eastern Policy of the United States (1938) pp 239-68

- ^ Zhitian Luo, "National humiliation and national assertion-The Chinese response to the twenty-one demands," Modern Asian Studies (1993) 27#2 pp 297-319.

- ^ Griswold, The Far Eastern Policy of the United States (1938) pp 326-28.

- ^ Clement (2009) p 75.

- ^ Roy Watson Curry, "Woodrow Wilson and Philippine Policy." Mississippi Valley Historical Review 41.3 (1954): 435-452. online

- ^ Tony Smith, America's mission: The United States and the worldwide struggle for democracy in the twentieth century (1994) pp 37-59.

- ^ Wong Kwok Chu, "The Jones Bills 1912–16: A Reappraisal of Filipino Views on Independence", Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 1982 13(2): 252–269

- ^ See Philippine Autonomy Act of 1916 (Jones Law)

- ^ Sonia M. Zaide, The Philippines: A Unique Nation (1994) p. 312.

- ^ Zaide, pp. 312–313.

- ^ H. W. Brands, Bound to empire: the United States and the Philippines (Oxford UP, 1992) pp 104-118.

- ^ "Fourteen Points | Text & Significance". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-02-07.

- ^ a b Margaret MacMillan (2003). Paris 1919 : six months that changed the world. Random House. pp. 63–82. ISBN 9780375508264.

- ^ Donald E. Davis and Eugene P. Trani (2009). Distorted Mirrors: Americans and Their Relations with Russia and China in the Twentieth Century. University of Missouri Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780826271891.

- ^ Bertrand M. Patenaude, "A Race against Anarchy: Even after the Great War ended, famine and chaos threatened Europe. Herbert Hoover rescued the continent, reviving trade, rebuilding infrastructure, and restoring economic order, holding a budding Bolshevism in check." Hoover Digest 2 (2020): 183-200 online

- ^ Douglas Smith, The Russian job: the forgotten story of how America saved the Soviet Union from ruin (2019) online

- ^ Betty Miller Unterberger, "President Wilson and the Decision to Send American Troops to Siberia." Pacific Historical Review 24.1 (1955): 63-74.

- ^ Eugene P. Trani, "Woodrow Wilson and the decision to intervene in Russia: a reconsideration." Journal of Modern History 48.3 (1976): 440-461.

- ^ Justus D. Doenecke, "Neutrality Policy and the Decision for War." in A Companion to Woodrow Wilson (2013): 241–269.

- ^ Philip Zelikow, The Road Less Traveled: The Secret Battle to End the Great War, 1916-1917 (PublicAffairs, 2021).

- ^ Joseph M. Siracusa, "American Policy-Makers, World War I, and the Menace of Prussianism, 1914-1920," Australasian Journal of American Studies (1998) 17#2 pp 1-30.

- ^ Jerald A Combs (2015). The History of American Foreign Policy: v.1: To 1920. pp. 325–. ISBN 9781317456377.

- ^ For a wartime American analysis see Charles A. Ellwood, "Making the world safe for democracy." The Scientific Monthly 7.6 (1918): 511-524 online.

- ^ Jeanette Keith (2004). Rich Man's War, Poor Man's Fight: Race, Class, and Power in the Rural South during the First World War. U. of North Carolina Press. pp. 1–5. ISBN 978-0-8078-7589-6.

- ^ Cooper, The Vanity of Power (1969) pp. 19–27, 202, 223–224.

- ^ "World War One". BBC History.

- ^ Link, Arthur S. (1972). Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era, 1910–1917. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 252–282.

- ^ H.J.Res.169: Declaration of War with Austria-Hungary, WWI, United States Senate

- ^ Andrew Patrick, "Woodrow Wilson, the Ottomans, and World War I." Diplomatic History 42.5 (2018): 886-910.

- ^ See US State Department, Office of the Historian, "Home Milestones 1914-1920 The Paris Peace Conference and the Treaty of Versailles" (2017). a US government document.

- ^ Margaret MacMillan, Paris 1919: Six months that changed the world (2007) p. 33.

- ^ Michael S. Neiberg, The Treaty of Versailles: A Concise History (Oxford UP, 2017) p. xvii.

- ^ H. Clarence Nixon, "Big Four" The Virginia Quarterly Review 19.4 (1943): 513-521. online

- ^ Neu (2015) p 416.

- ^ On Italy and Wilson see Arthur Walworth, Wilson and his Peacemakers: American Diplomacy at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919 (WW Norton, 1986) pp 335–358.

- ^ George Kennan, . "Russia and the Versailles Conference." The American Scholar (1960): 13-42 online

- ^ Margaret MacMillan, Paris 1919: Six months that changed the world (Random House, 2001) pp 63–82.

- ^ MacMillan, Paris 1919 (2001) pp 194–203.

- ^ Ralph A. Stone, ed. Wilson and the League of Nations: why America's rejection? (1967) pp 1-11.

- ^ Theodore P. Greene, ed. Wilson At Versailles (1957) "Introduction" pp v to x. online

- ^ Patricia O'Toole, The Moralist: Woodrow Wilson and the World He Made (2019) pp. xv to xvii.

- ^ Richard M. Gamble, "Savior Nation: Woodrow Wilson and the Gospel of Service," Humanitas 14#1 1(2001) pp 4+.

- ^ F. M. Carroll, "Wilsonian Diplomacy: Friends and Enemies." Canadian Review of American Studies 19.2 (1988): 211-226.

- ^ Tony Smith, America's Mission: The United States and the Worldwide Struggle for Democracy (Princeton University Press, 2012) pp 60-83.

- ^ John L. Snell, "Wilson on Germany and the fourteen points." Journal of Modern History 26.4 (1954): 364-369 online.

- ^ Irwin Unger, These United States (2007) 561.

- ^ "Wilson's Fourteen Points, 1918 - 1914–1920 - Milestones - Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 2022-01-06.

- ^ Margaret MacMillan, Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World (2007) pp 83–97.

- ^ John A. Thompson, "Wilsonianism: the dynamics of a conflicted concept." International Affairs 86.1 (2010): 27-47.

- ^ David Fromkin, "What Is Wilsonianism?" World Policy Journal 11.1 (1994): 100-111 online.

- ^ Amos Perlmutter, Making the world safe for democracy: A century of Wilsonianism and its totalitarian challengers (U of North Carolina Press, 1997).

- ^ Trygve Throntveit, "Wilsonianism." in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History (2019).

- ^ "Woodrow Wilson and foreign policy". EDSITEment. National Endowment for the Humanities.

- ^ a b c Anne-Marie Slaughter, "Wilsonianism in the Twenty-first Century" in The Crisis of American Foreign Policy: Wilsonianism in the Twenty-first Century (edited by G. John Ikenberry, Thomas J. Knock, Anne Marie-Slaughter & Tony Smith: Princeton UP, 2009), pp. 94-96.

- ^ Erez Manela, The Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism (2007), pp. 41-42.

- ^ "Woodrow Wilson, Impact and Legacy". Miller Center. 4 October 2016. Retrieved 2018-01-07.

- ^ a b c Lloyd E. Ambrosius (2002). Wilsonianism: Woodrow Wilson and His Legacy in American Foreign Relations. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 42–51.

- ^ Nicholas J. Cull, "Public Diplomacy Before Gullion: The Evolution of a Phrase" in Nancy Snow & Philip M. Taylor, eds. Routledge Handbook of Public Diplomacy (Routledge: 2009).

- ^ Joel Ira Holwitt, "Execute Against Japan": The U.S. Decision to Conduct Unrestricted Submarine Warfare (Texas A&M Press, 2008), pp. 16-17.

- ^ David M. Kennedy, "What 'W' Owes to 'WW': President Bush May Not Even Know It, but He Can Trace His View of the World to Woodrow Wilson, Who Defined a Diplomatic Destiny for America That We Can't Escape." The Atlantic Monthly Vol: 295. Issue: 2. (March 2005) pp 36+.

- ^ For the presidential implementation of Wilsonianism see Tony Smith, America's Mission: The United States and the Worldwide Struggle for Democracy (2nd ed. Princeton University Press, 2012).

- ^ Walter Russell Mead, Special Providence, (2001)

- ^ Lloyd E. Ambrosius, "Woodrow Wilson and World War I." in A Companion to American Foreign Relations (2006): 149-167.

- ^ Ambrosius, p. 149-150.

- ^ David G. Haglund, and Deanna Soloninka. "Woodrow Wilson Still Fuels Debate on 'Who Lost Russia?'." Orbis 60.3 (2016): 433-452.

- ^ Lloyd E. Ambrosius, "Woodrow Wilson and George W. Bush: Historical comparisons of ends and means in their foreign policies." Diplomatic History 30.3 (2006): 509-543.

- ^ Bruce S. Thornton, "The Arab Spring implodes: we failed to understand the wave of change--or to shape it--because we failed to understand Islamism." Hoover Digest 2 (2014): 130-138.

- ^ Tony Smith, “Wilsonianism after Iraq." in The Crisis of American Foreign Policy (Princeton University Press, 2008) pp. 53-88.

Sources[edit]

The source for 1919 is US State Department, Office of the Historian, "Home Milestones 1914-1920 The Paris Peace Conference and the Treaty of Versailles" (2017), a U.S. government document that is not copyright.

Further reading[edit]

General[edit]

- Calhoun, Frederick S. Power and Principle: Armed Intervention in wilsonion Foreign Policy (Kent State UP, 1986).

- Clements, Kendrick A. (1992). The Presidency of Woodrow Wilson. University Press of Kansas.; covers all major foreign policy issues

- Combs, Jerald A. The History of American Foreign Policy: From 1895 (Routledge, 2017), textbook

- Gardner, Lloyd C. Safe for democracy: the Anglo-American response to revolution, 1913-1923 (Oxford UP, 1984).

- Hannigan, Robert E. The New World Power (U of Pennsylvania Press, 2013. excerpt

- Herring, George C. From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776 (Oxford UP, 2008) online, textbook

- Link, Arthur S. Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era, 1910–1917 (1954), major scholarly survey online; brief summary of Link biography vol 2-3-4-5

- Link, Arthur S. Wilson the Diplomatist: A Look at His Major Foreign Policies (1957) online

- Link, Arthur S. ed. Woodrow Wilson and a Revolutionary World, 1913–1921 (1982). essays by 7 scholars online

- Perkins, Bradford. The Great Rapprochement: England and the United States, 1895–1914 (1968). online

- Reed, James. The Missionary Mind and American East Asian Policy, 1911–1915 (Harvard UP, 1983).

- Robinson, Edgar Eugene, and Victor J. West. The Foreign Policy of Woodrow Wilson, 1913-1917 online useful survey with many copies of primary sources.

- Smith, Tony. America's mission call in the United States and the worldwide struggle for democracy in the twentieth century (1994).

- Wells, Samuel F. (1972). "New Perspectives on Wilsonian Diplomacy: The Secular Evangelism of American Political Economy". Perspectives in American History. 6: 389–419.

World War I[edit]

- Ambrosius, Lloyd E. "Woodrow Wilson and World War I" in A Companion to American Foreign Relations, edited by Robert D. Schulzinger. (2003).

- Bruce, Robert B. A Fraternity of Arms: America and France in the Great War (UP of Kansas. 2003).

- Clarke, Michael. "Primacy Unrequited: American Grand Strategy Under Wilson." in American Grand Strategy and National Security (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2021) pp. 117–150.

- Clements, Kendrick A. (2004). "Woodrow Wilson and World War I". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 34: 62–82. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2004.00035.x.

- Cooper, Jr., John Milton. The Vanity of Power: American Isolationism and the First World War 1914-1917 (Greenwood, 1969). online

- Dayer, Roberta A. (1976). "Strange Bedfellows: J. P. Morgan & Co., Whitehall and the Wilson Administration During World War I". Business History. 18 (2): 127–151. doi:10.1080/00076797600000014.

- Doenecke, Justus D. (2013). "Neutrality Policy and the Decision for War". A Companion to Woodrow Wilson. pp. 241–269. doi:10.1002/9781118445693.ch13. ISBN 9781118445693.

- Doenecke, Justus D. Nothing less than war: a new history of America's entry into World War I (UP of Kentucky, 2011).

- Doerries, Reinhard R. Imperial Challenge: Ambassador Count Bernstorff and German-American Relations, 1908-1917 (1989).

- Epstein, Katherine C. “The Conundrum of American Power in the Age of World War I,” Modern American History (2019): 1-21.

- Esposito, David M. The Legacy of Woodrow Wilson: American War Aims in World War I. (1996).

- Ferns, Nicholas (2013). "Loyal Advisor? Colonel Edward House's Confidential Trips to Europe, 1913–1917". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 24 (3): 365–382. doi:10.1080/09592296.2013.817926. S2CID 159469024.

- Flanagan, Jason C. "Woodrow Wilson's" Rhetorical Restructuring": The Transformation of the American Self and the Construction of the German Enemy." Rhetoric & Public Affairs 7.2 (2004): 115-148. online[dead link]

- Floyd, Ryan. Abandoning American Neutrality: Woodrow Wilson and the Beginning of the Great War, August 1914–December 1915 (Springer, 2013).

- Gilbert, Charles. American financing of World War I (1970) online

- Hannigan, Robert E. (2017). The Great War and American Foreign Policy, 1914-24. doi:10.9783/9780812293289. ISBN 9780812293289.

- Horn, Martin. Britain, France, and the Financing of the First World War (2002), with details on US role

- Kawamura, Noriko. Turbulence in the Pacific: Japanese-US Relations During World War I (Greenwood, 2000).

- Kazin, Michael. War Against War: The American Fight for Peace, 1914-1918 (2017).

- Kennedy, Ross A. "Wilson's Wartime Diplomacy: The United States and the First World War, 1914–1918." in A Companion to US Foreign Relations: Colonial Era to the Present (2020): 304–324.

- Kennedy, Ross A. (2001). "Woodrow Wilson, World War I, and American National Security". Diplomatic History. 25: 1–32. doi:10.1111/0145-2096.00247.

- Kernek, Sterling J. (1975). "Distractions of Peace during War: The Lloyd George Government's Reactions to Woodrow Wilson, December, 1916-November, 1918". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 65 (2): 1–117. doi:10.2307/1006183. JSTOR 1006183.

- Levin Jr., N. Gordon. Woodrow Wilson and World Politics: America's Response to War and Revolution (Oxford UP, 1968), New Left approach.

- McAvoy, Shawn (2021). "'We should not expect great benefit from America': Japanese Expansion and the Breakdown of Communication within the Wilson Administration in 1914". Journal of Asia Pacific Studies. 6 (2): 163–174. EBSCOhost 152071887.

- May, Ernest R. The World War and American isolation : 1914-1917 (1959) online, a major scholarly study

- Mayer, Arno J. Wilson vs. Lenin: Political Origins of the New Diplomacy 1917-1918 (1969)

- Safford, Jeffrey J. Wilsonian Maritime Diplomacy, 1913–1921. 1978.

- Smith, Daniel M. The Great Departure: The United States in World War I, 1914-1920 (1965).

- Startt, James D. Woodrow Wilson, the Great War, and the Fourth Estate (Texas A&M UP, 2017) 420 pp.

- Stevenson, David. The First World War and International Politics (1991), Covers the diplomacy of all the major powers.

- Throntveit, Trygve (2017). Power without Victory. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226460079.001.0001. ISBN 9780226459905.

- Trask, David F. The United States in the Supreme War Council: American War Aims and Inter-Allied Strategy, 1917-1918 (1961)

- Tooze, Adam. The Deluge: The Great War, America and the Remaking of the Global Order, 1916-1931 (2014) audio; emphasis on economics

- Tucker, Robert W. Woodrow Wilson and the Great War: Reconsidering America’s Neutrality (U of Virginia Press, 2007).

- Venzon, Anne ed. The United States in the First World War: An Encyclopedia (1995), Very thorough coverage.

- Walworth, Arthur. America's moment, 1918: American diplomacy at the end of World War I (1977) online

- Woodward, David R. Trial by Friendship: Anglo-American Relations, 1917–1918 (1993).

- Wright, Esmond (March 1960). "The Foreign Policy of Woodrow Wilson: A Re-Assessment. Part 1: Woodrow Wilson and the First World War". History Today. 10 (3): 149–157.

- Young, Ernest William. The Wilson Administration and the Great War (1922) online edition

- Zahniser, Marvin R. Uncertain Friendship: American-French diplomatic relations through the Cold War (1975). pp 195–229.

- Ferguson, Niall (9 April 2021). "All the difference: The peacemaking initiative that failed, at vast cost". Times Literary Supplement. No. 6158. pp. 23–26. Gale A658753511.; also C-SPAN interview;

Latin America[edit]

- Baker, George W. "The Wilson Administration and Nicaragua, 1913–1921." The Americas 22.4 1966): 339–376.

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg. The Latin American Policy of the United States. (1943) pp 168–201 online

- Boghardt, Thomas. The Zimmermann telegram: intelligence, diplomacy, and America's entry into World War I (Naval Institute Press, 2012).

- De Quesada, Alejandro. The Hunt for Pancho Villa: The Columbus Raid and Pershing’s Punitive Expedition 1916–17 (Bloomsbury, 2012).

- Gardner, Lloyd C. Safe for democracy: the Anglo-American response to revolution, 1913-1923 (Oxford UP, 1984).

- Gilderhus, Mark T. Diplomacy and Revolution: US-Mexican Relations under Wilson and Carranza (1977). online

- Haley, P. Edward. Revolution and Intervention: The Diplomacy of Taft and Wilson with Mexico, 1910-1917 (MIT Press, 1970).

- Hannigan, Robert E. The New World Power (U of Pennsylvania Press, 2013. excerpt

- Katz, Friedrich. The Secret War in Mexico: Europe, the United States, and the Mexican Revolution (1981). online

- McPherson, Alan. A Short History of US Interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean(John Wiley & Sons, 2016).

- Neagle, Michael E. "A Bandit Worth Hunting: Pancho Villa and America’s War on Terror in Mexico, 1916-1917." Terrorism and Political Violence 33.7 (2021): 1492–1510.

- Quirk, Robert E. An affair of honor: Woodrow Wilson and the occupation of Veracruz (1962). on Mexico online

- Sandos, James A. "Pancho Villa and American Security: Woodrow Wilson's Mexican Diplomacy Reconsidered" Journal of Latin American Studies 13#2 (1981): 293–311. online

- Tuchman, Barbara W. (1985). The Zimmermann Telegram. ISBN 0-345-32425-0.

- Sherman, David. "Barbara Tuchman’s The Zimmermann Telegram: secrecy, memory, and history." Journal of Intelligence History 19.2 (2020): 125–148.

Biographical[edit]

- Ambrosius, Lloyd E. (2006). "Woodrow Wilson and George W. Bush: Historical Comparisons of Ends and Means in Their Foreign Policies". Diplomatic History. 30 (3): 509–543. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7709.2006.00563.x.

- Clements, Kendrick A. Woodrow Wilson: World Statesman (1987) 288pp; major scholarly biography excerpt

- Clements, Kendrick A. William Jennings Bryan, missionary isolationist (U of Tennessee Press, 1982) online; focus on foreign policy.

- Cooper, John Milton. Woodrow Wilson: A Biography (2009) online; major scholarly biography

- Doerries, Reinhard R. Imperial Challenge: Ambassador Count Bernstorff and German-American Relations, 1908-1917 (1989)

- Ferns, Nicholas (September 2013). "Loyal Advisor? Colonel Edward House's Confidential Trips to Europe, 1913–1917". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 24 (3): 365–382. doi:10.1080/09592296.2013.817926. S2CID 159469024.

- Fowler, Wilton Bonham (1966). Sir William Wiseman and the Anglo-American war partnership, 1917-1918 (Thesis). OCLC 51693434. ProQuest 302236948.

- Graebner. Norman A. ed An Uncertain Tradition: American Secretaries of State in the Twentieth Century (1961) covers Bryan (pp 79–100) and Lansing (pp 101–127) online.

- Heckscher, August (1991). Woodrow Wilson. Easton Press. online

- Hodgson, Godfrey. Woodrow Wilson's Right Hand: The Life of Colonel Edward M. House. (2006); short popular biography online

- Lazo, Dimitri D. "A question of Loyalty: Robert Lansing and the Treaty of Versailles." Diplomatic History 9.1 (1985): 35–53.

- Link, Arthur Stanley. Wilson. online

- Wilson: The New Freedom vol 2 (1956)

- Wilson: The Struggle for Neutrality: 1914–1915 vol 3 (1960)

- Wilson: Confusions and Crises: 1915–1916 vol 4 (1964)

- Wilson: Campaigns for Progressivism and Peace: 1916–1917 vol 5 (1965)

- Neu, Charles E. Colonel House: A Biography of Woodrow Wilson's Silent Partner (Oxford UP, 2015), 699 pp

- Neu, Charles E. The Wilson Circle: President Woodrow Wilson and His Advisers (2022)

- O'Toole, Patricia. The Moralist: Woodrow Wilson and the World He Made (2018)

- Walworth, Arthur (1958). Woodrow Wilson, Volume I, Volume II. Longmans, Green.; 904pp; full scale scholarly biography; winner of Pulitzer Prize; online free 2nd ed. 1965

- Walworth, Arthur. Wilson and His Peacemakers: American Diplomacy at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919 (1986). online

- Williams, Joyce Grigsby. Colonel House and Sir Edward Grey: A Study in Anglo-American Diplomacy (1984) online review

- Woolsey, Lester H. "Robert Lansing's Record as Secretary of State." Current History 29.3 (1928): 384–396. online

Peace treaties and Wilsonianism[edit]

- Ambrosius, Lloyd E. Woodrow Wilson and the American diplomatic tradition: The treaty fight in perspective (Cambridge UP, 1990) online.

- Ambrosius, Lloyd E. "Wilson, the Republicans, and French Security after World War I." Journal of American History (1972): 341–352. Online

- Ambrosius, Lloyd E. "World War I and the Paradox of Wilsonianism." Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 17.1 (2018): 5-22.

- Ambrosius, Lloyd E. Wilsonian Statecraft: Theory and Practice of Liberal Internationalism During World War I (1991).

- Ambrosius, Lloyd E. (2002). Wilsonianism. doi:10.1057/9781403970046. ISBN 978-1-4039-6009-2.

- Bacino, Leo C. Reconstructing Russia: US policy in revolutionary Russia, 1917-1922 (Kent State UP, 1999) online.

- Bailey, Thomas A. Woodrow Wilson and the Lost Peace (1963) on Paris, 1919 online

- Bailey, Thomas A. Woodrow Wilson and the great betrayal (1945) on Senate defeat. conclusion-ch 22; online

- Birdsall, Paul Versailles Twenty Years After (1941).

- Canfield, Leon H. The Presidency of Woodrow Wilson; prelude to a world in crisis (1966) online

- Cooper, John Milton, Jr. Breaking the Heart of the World: Woodrow Wilson and the Fight for the League of Nations (2001). online

- Curry, George. "Woodrow Wilson, Jan Smuts, and the Versailles Settlement." American Historical Review 66.4 (1961): 968–986. Online

- Duff, John B. "The Versailles Treaty and the Irish-Americans." Journal of American History 55.3 (1968): 582–598. Online

- Fifield, R H. Woodrow Wilson and the Far East: the diplomacy of the Shantung question (Thomas Y. Crowell, 1952).

- Graebner, Norman A. and Edward M. Bennett, eds. The Versailles Treaty and Its Legacy: The Failure of the Wilsonian Vision (Cambridge UP, 2011).

- Floto, Inga. Colonel House in Paris: A Study of American Policy at the Paris Peace Conference 1919 (Princeton UP, 1980).

- Foglesong, David S. "Policies toward Russia and intervention in the Russian revolution." in A Companion to Woodrow Wilson (2013): 386–405.

- Greene, Theodore, ed. Wilson At Versailles (1949) short excerpts from scholarly studies. online free

- Ikenberry, G. John, Thomas J. Knock, Anne-Marie Slaughter, and Tony Smith. The Crisis of American Foreign Policy: Wilsonianism in the Twenty-first Century (Princeton UP, 2009) online

- Jianbiao, Ma. "“At Gethsemane”: The Shandong Decision at the Paris Peace Conference and Wilson's identity crisis." Chinese Studies in History 54.1 (2021): 45-62.

- Kendall, Eric M. "Diverging Wilsonianisms: Liberal Internationalism, the Peace Movement, and the Ambiguous Legacy of Woodrow Wilson" (PhD. Dissertation, Case Western Reserve University, 2012). online 354pp; with bibliography of primary and secondary sources pp 346–54.

- Kennedy, Ross A. The will to believe: Woodrow Wilson, World War I, and America's strategy for peace and security (Kent State UP, 2008).

- Knock, Thomas J. To End All Wars: Woodrow Wilson and the Quest for a New World Order (Princeton UP, 1992). online

- Macmillan, Margaret. Paris 1919: Six Months That Changed the World (2001). online

- Menchik, Jeremy. "Woodrow Wilson and the Spirit of Liberal Internationalism." Politics, Religion & Ideology (2021): 1-23.

- Perlmutter, Amos. Making the world safe for democracy : a century of Wilsonianism and its totalitarian challengers (1997) online

- Pierce, Anne R. Woodrow Wilson & Harry Truman: Mission and Power in American Foreign Policy (Routledge, 2017).

- Powaski, Ronald E. (2017). "Woodrow Wilson Versus Henry Cabot Lodge: The Battle over the League of Nations, 1918–1920". American Presidential Statecraft. pp. 67–111. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-50457-5_3. ISBN 978-3-319-50456-8.

- Roberts, Priscilla. "Wilson, Europe's Colonial Empires," in A Companion to Woodrow Wilson (2013): 492+ online.

- Smith, Tony. Why Wilson Matters: The Origin of American Liberal Internationalism and Its Crisis Today (Princeton University Press, 2017)

- Smith, Tony. America's Mission: The United States and the Worldwide Struggle for Democracy (2nd ed. Princeton UP, 2012).

- Stone, Ralph A. ed. Wilson and the League of Nations: why America's rejection? (1967) short excerpts from 15 historians.

- Stone, Ralph A. The irreconcilables; the fight against the League of Nations (1970) online

- Tillman, Seth P. Anglo-American relations at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 (https://archive.org/details/angloamericanrel0000till) [1961 online]

- Walworth, Arthur. Wilson and his Peacemakers: American Diplomacy at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919 (WW Norton, 1986) online

- Wolff, Larry. Woodrow Wilson and the Reimagining of Eastern Europe (Stanford University Press, 2020) online review.

- Wright, Esmond. "The Foreign Policy of Woodrow Wilson: A Re-Assessment. Part 2: Wilson and the Dream of Reason" History Today (Apr 1960) 19#4 pp 223–231

Historiography[edit]

- Ambrosius, Lloyd E. "Woodrow Wilson and Wilsonianism a Century Later." (2020). online

- Cooper, John Milton. "The World War and American Memory" Diplomatic History (2014) 38#4 pp 727–736. online.

- Doenecke, Justus D. "American Diplomacy, Politics, Military Strategy, and Opinion‐Making, 1914–18: Recent Research and Fresh Assignments." Historian 80.3 (2018): 509–532.

- Doenecke, Justus D. The Literature of Isolationism: A Guide to Non-Interventionist Scholarship, 1930-1972 (R. Myles, 1972).

- Doenecke, Justus D. Nothing Less Than War: A New History of America's Entry into World War I (2014)

- Fordham, Benjamin O. "Revisionism reconsidered: exports and American intervention in World War I." International Organization 61#2 (2007): 277–310.

- Gerwarth, Robert. "The Sky beyond Versailles: The Paris Peace Treaties in Recent Historiography." Journal of Modern History 93.4 (2021): 896-930.

- Herring, Pendleton (1974). "Woodrow Wilson—Then and Now". PS: Political Science & Politics. 7 (3): 256–259. doi:10.1017/S1049096500011422. S2CID 155226093.

- Keene, Jennifer D. (2016). "Remembering the "Forgotten War": American Historiography on World War I". Historian. 78 (3): 439–468. doi:10.1111/hisn.12245. S2CID 151761088.

- Kennedy, Ross A. ed. A Companion to Woodrow Wilson (2013) online[permanent dead link] coverage of major scholarly studies by experts

- McKillen, Elizabeth. "Integrating labor into the narrative of Wilsonian internationalism: A literature review." Diplomatic History 34.4 (2010): 643–662.

- Neiberg, Michael S. (2018). "American Entry into the First World War as an Historiographical Problem". The Myriad Legacies of 1917. pp. 35–54. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-73685-3_3. ISBN 978-3-319-73684-6.

- Saunders, Robert M. "History, Health and Herons: The Historiography of Woodrow Wilson's Personality and Decision-Making." Presidential Studies Quarterly (1994): 57–77. in JSTOR

- Sharp, Alan. Versailles 1919: A Centennial Perspective (Haus Publishing, 2018).

- Showalter, Dennis. “The United States in the Great War: A Historiography.” OAH Magazine of History 17#1 (2002), pp. 5–13, online

- Steigerwald, David. "The Reclamation of Woodrow Wilson?" Diplomatic History 23.1 (1999): 79–99. pro-Wilson online

- Thompson, J. A. (1985). "Woodrow Wilson and World War I: A Reappraisal". Journal of American Studies. 19 (3): 325–348. doi:10.1017/S0021875800015310. S2CID 145071620.