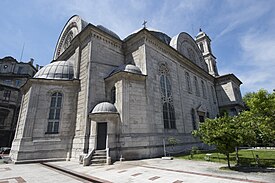

Hagia Triada Church, Istanbul

| Hagia Triada Greek Orthodox Church | |

|---|---|

Hagia Triada Church | |

| 41°02′08″N 28°59′03″E / 41.0355°N 28.9842°E | |

| Location | Beyoğlu, Istanbul, Turkey |

| Denomination | Greek Orthodox |

| History | |

| Dedicated | 1880 |

| Cult(s) present | Holy Trinity |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Konstantis Yolasığmazis |

| Architectural type | Domed single nave basilica |

| Style | Neo-Baroque and Neo-Byzantine |

| Groundbreaking | 13 August 1876 |

| Completed | 14 September 1880 |

| Specifications | |

| Number of domes | 1 |

| Number of spires | 2 |

| Administration | |

| Metropolis | Patriarchate of Constantinople |

Hagia Triada ("Holy Trinity"; Greek: Ιερός Ναός Αγίας Τριάδος, romanized: Ierós Naós Agías Triádos; Turkish: Aya Triada Rum Ortodoks Kilisesi) is a Greek Orthodox church in Istanbul, Turkey. The building was erected in 1880 and is considered the largest Greek Orthodox shrine in Istanbul today.[1] It is still in use by the Greek community of Istanbul.[2][3] It has about 150 parishioners.[4] The church is located in the district of Beyoğlu, in the neighborhood of Katip Çelebi, on Meşelik sokak, near Taksim Square.[5]

History[edit]

The property where the Church stands used to be the site of a Greek Orthodox cemetery and hospital.[6] This was demolished in order to build the Church. Its construction, based on the designs of the Ottoman Greek architect P. Kampanaki, began on 13 August 1876 and was completed on 14 September 1880.[2][7][8] The Church is built in neo-baroque style with elements of a basilica,[9] and with the unusual features of twin bell towers, a large dome and a neo-gothic facade.[2] The Hagia Triada was the first domed Christian church that was allowed to be built in Istanbul after the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.[9]

Architectural elements such as the dome of the church were only allowed after 1839 during a period known as the Tanzimat under which the restrictions limiting the Freedom of Speech for minorities were loosened and domes were allowed to be constructed as design features of Christian churches.[2]

The paintings and decorations of the church's interior are the work of painter Sakellarios Megaklis, while the marble works and designs were created by sculptor Alexandros Krikelis.[10] On Church grounds there is also a school, Zapyon Rum Lisesi (Zappeion Greek Lyceum), which continues to serve the Greek community of Istanbul.[11] In the church courtyard there are additional buildings dedicated to social services and also a sacred spring.[9]

Damage and restoration[edit]

The Hagia Triada Church was damaged and set on fire during the Istanbul pogrom of 6–7 September 1955 by an organized mob attack directed primarily at Istanbul's Greek minority.[12][13][14][15] During the unrest, the Church was wrecked and pillaged but withstood an attempted arson attack by the rioters.[13][16][17][18] According to ethnic Armenian actor Nubar Terziyan, who witnessed the incident, the mob arrived at the Church and started the fire by dumping kerosene onto the Church and lighting it with burning sticks.[19]

Decades after the events, industrialist and businessman Panagiotis Angelopoulos, who was given the titles Megas Archon Logothetes and Great Benefactor by the Patriarchate of Constantinople, donated the sum of US$90,000 to Patriarch Bartholomew; the funds were used for repairs and renovations of the church which lasted two years.[20]

The inauguration took place on 23 March 2003 and the official opening of the gate of the church was attended by many officials of the Greek Orthodox Church as well as the consuls general of Greece, France and Germany and hundreds of people from Istanbul and Greece. The inaugural speech was delivered by Patriarch Bartholomew. The church is now used on a daily basis.[20]

Gallery[edit]

-

Dome of Hagia Triada Greek Orthodox Church

-

Dome of Hagia Triada Greek Orthodox Church

-

Hagia Triada Greek Orthodox Church front

-

Hagia Triada Greek Orthodox Church interior

-

Hagia Triada Greek Orthodox Church iconostasis

-

Hagia Triada Greek Orthodox Church balcony7

-

The door of the church

-

Details of the windows

See also[edit]

- Aya Triada Greek Orthodox Church, 360 Degree Virtual Tours (Internal and External) All Areas

- Photo gallery of the church

- Christianity in Turkey

- Greeks in Turkey

- Taksim Square Mosque

- Cyril VII of Constantinople

- Constantine V of Constantinople

References[edit]

- ^ Levine, Emma. Frommer's Istanbul Day By Day (2nd ed.). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119972341.

- ^ a b c d "Aya Triada Kilisesi (Holy Trinity Church)". Istanbul: The Guide. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ Çelik, Zeynep (1993). The remaking of Istanbul : portrait of an Ottoman city in the nineteenth century (1. paperback printing. ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520082397.

- ^ "Εκκλησίες της Ομογένειας". omogeneia-turkey.

- ^ Göktürk, edited by Deniz; Soysal, Levent; Türeli, Ipek (2010). Orienting Istanbul : cultural capital of Europe?. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415580106.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ "TAKSIM / AYA TRIADA RUM ORTODOKS KILISESI" (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ "Travel Guide to Turkey". Turkey Web Guide. Archived from the original on 27 November 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ E.Şarlak, İstanbul’un 100 Kilisesi, İstanbul Büyükşehir Belediyesi Kültür A.Ş Yayınları,İstanbul 2010, pg. 93-95

- ^ a b c "Taksim Aya Triada Greek Orthodox Church". byzantiumistanbul. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ "Taksim Aya Triada Rum Ortodoks Kilisesi" (in Turkish). Byzantiumistanbul. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ "Degisti". Degisti.com. Archived from the original on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ Archbishop Iakovos of the Americas (10 September 1995). Σεπτέμβριος 1955: η τρίτη άλωση (PDF). Kathimerini (in Greek). p. 32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- ^ a b Vryonis, Speros (2005). The mechanism of catastrophe: the Turkish pogrom of September 6-7, 1955 and the destruction of the Greek community of Istanbul (3. printing. ed.). New York: Greekworks.com. p. 430. ISBN 9780974766034.

Aghia Triada, Taksim - Wrecked, pillaged and destroyed by fire.

- ^ Güven, Dilek (2005-09-06). "6–7 Eylül Olayları (1)". Radikal (in Turkish).

- ^ Kuyucu, Ali Tuna (2005). "Ethno-religious 'unmixing' of 'Turkey': 6–7 September riots as a case in Turkish nationalism". Nations and Nationalism. 11 (3): 361–380. doi:10.1111/j.1354-5078.2005.00209.x.

- ^ Uluç, Hıncal (7 February 2012). "Meydansiz Istanbul'un son meydani". Sabah (in Turkish). Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ Özdoğan, Günay Göksu (2009). Türkiye'de Ermeniler: cemaat, birey, yurttaş (in Turkish) (1. baskı. ed.). Şişli, İstanbul: İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları. ISBN 9786053990956.

- ^ "Nubar Terziyan 6-7 Eylül'ü anlatıyor". Agos (in Turkish). September 28, 2012. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ a b Panayotis Rizopoulos (September 2005). "Ιερός Ναός Αγίας Τριάδος Σταυροδρομίου Κωνσταντινουπόλεως 1880 – 2005, 125 χρόνια ζωής και προσφοράς στην ομογένεια της Πόλης". orthodoxia.gr. Archived from the original on 27 June 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2013.