History of Mexico

| History of Mexico |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The written history of Mexico spans more than three millennia. First populated more than 13,000 years ago,[1] central and southern Mexico (termed Mesoamerica) saw the rise and fall of complex indigenous civilizations. Mesoamerican civilizations developed glyphic writing systems, recording the political history of conquests and rulers. Mesoamerican history before European arrival is called the prehispanic era or the pre-Columbian era. The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire established the colony of New Spain, leading to the imposition of Spanish rule over the indigenous populations, the spread of Christianity, the exploitation of natural resources, and the introduction of new crops, animals, and diseases.

A prolonged struggle ensued in order to attain independence against Spain. Social inequalities, necessity for economic growth (independent from Spain), and the spread of republican ideals free from European monarchies contributed to independence movements against Spain. These movements included the "Grito De Dolores (Cry of Dolores)," lead predominately by Catholic priest, Miguel Hidalgo. Hidalgo remained a prominent figure of the independence movement up until he was capture and execution by the Spanish. The events transpired by Hidalgo kickstarted the events which later contributed to Mexico's offical Declaration of Independence against Spain in 1821.

After the Mexican War of Independence (1810-1821), Mexico struggled to establish stability amid regional conflicts and power struggles among caudillos, competing factions, separatist movements, and foreign intervention. The mid-19th century Reforma saw efforts to modernize Mexican society, including the promotion of civil liberties and the separation of church and state. Yet, Mexico faced continued challenges, including the Reform War, French intervention (1861-1867), and the subsequent establishment of the short-lived Second Mexican Empire. The late 19th century Porfiriato (1876-1911) was characterized by economic growth but also marked by authoritarianism and social inequality. Long-standing grievances, including land dispossession, exploitation of labor, and lack of representation led to the Mexican Revolution in 1910. The revolution quickly escalated into a protracted conflict involving several factions, with the Constitutionalists emerging victorious in 1920.

After the Revolution, the Institutional Revolutionary Party emerged as the dominant political force, maintaining power through a combination of patronage, authoritarianism, and corporatism. In the following decades, Mexico implemented land reform, nationalized key industries, and expanded social welfare programs. However, political stability and economic growth were often marred by corruption, repression, and violence. Following economic crises in the 1970s and 1980s, policies shifted towards privatization and trade liberalization. The signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994 led to greater integration into the global economy, but also deindustrialization and social unrest. The end of the century saw the PRI's long-standing grip on power challenged, culminating in the opposition National Action Party (PAN) winning the presidency in 2000, marking a shift in Mexico's political landscape.

Pre-Columbian civilizations[edit]

Large and complex civilizations developed in the center and southern regions of Mexico (with the southern region extending into what is now Central America) in what has come to be known as Mesoamerica. The civilizations that rose and declined over millennia were characterized by:[2]

- significant urban settlements;

- monumental architecture such as temples, palaces, and other monumental architecture, such as the ball court;

- the division of society into religious and political elites (such as warriors and merchants) and commoners who pursued subsistence agriculture;

- transfer of tribute and rending of labor from commoners to elites;

- reliance on agriculture often supplemented by hunting and fishing and the complete absence of a pastoral (herding) economy since there were no domesticated herd animals before the arrival of the Europeans;

- trade networks and markets.

The history of Mexico before the Spanish conquest is known through the work of archaeologists, epigraphers, and ethnohistorians, who analyze Mesoamerican indigenous manuscripts, particularly Aztec codices, Mayan codices, and Mixtec codices. Accounts written by Spaniards at the time of the conquest (the conquistadores) and by Indigenous chroniclers of the postconquest period constitute the principal source of information regarding Mexico at the time of the Spanish Conquest. Few pictorial manuscripts (or codices) of the Maya, Mixtec, and Mexica cultures of the Post-Classic period survive, but progress has been made particularly in the area of Maya archaeology and epigraphy.[3]

Beginnings[edit]

The presence of people in Mesoamerica was once thought to date back 40,000 years, an estimate based on what were believed to be ancient footprints discovered in the Valley of Mexico. This date may not be accurate after further investigation using radiocarbon dating.[4] It is currently unclear whether 23,000-year-old campfire remains found in the Valley of Mexico are the earliest human remains uncovered so far in Mexico.[5] The first people to settle in Mexico encountered a climate far milder than the current one. In particular, the Valley of Mexico contained several large paleo-lakes (known collectively as Lake Texcoco) surrounded by dense forest. Deer were found in this area, but most fauna were small land animals and fish and other lacustrine animals were found in the lake region.[6] Such conditions encouraged the initial pursuit of a hunter-gatherer existence. Indigenous peoples in western Mexico began to selectively breed maize (Zea mays) plants between 5,000 and 10,000 years ago.[7] The diet of ancient central and southern Mexico was varied, including domesticated corn (or maize), squashes, beans, tomatoes, peppers, cassavas, pineapples, chocolate, and tobacco. The Three Sisters (corn, squash, and beans) constituted the principal diet.[8]

Mesoamericans had belief systems where every element of the cosmos and everything that forms part of nature represented a supernatural manifestation. The spiritual pantheon was vast and extremely complex. They frequently took on different characteristics and even names in other areas, but in effect, they transcended cultures and time. Great masks with gaping jaws and monstrous features in stone or stucco were often located at the entrance to temples, symbolizing a cavern or cave on the flanks of the mountains that allowed access to the depths of Mother Earth and the shadowy roads that lead to the underworld.[9] Cults connected with the jaguar and jade especially permeated religion throughout Mesoamerica. Jade, with its translucent green color, was revered along with water as a symbol of life and fertility. The jaguar, agile, powerful, and fast, was especially connected with warriors and as spirit guides of shamans. Despite differences in chronology or geography, the crucial aspects of this religious pantheon were shared amongst the people of ancient Mesoamerica.[9] Thus, this quality of acceptance of new gods to the collection of existing gods may have been one of the shaping characteristics for success during the Christianization of Mesoamerica. New gods did not at once replace the old; they initially joined the ever-growing family of deities or were merged with existing ones that seemed to share similar characteristics or responsibilities.[9]

Mesoamerica is the only place in the Americas where Indigenous writing systems were invented and used before European colonization. While the types of writing systems in Mesoamerica range from minimalist "picture-writing" to complex logophonetic systems capable of recording speech and literature, they all share some core features that make them visually and functionally distinct from other writing systems of the world.[10] Although many indigenous manuscripts have been lost or destroyed, texts known as Aztec codices, Mayan codices, and Mixtec codices still survive and are of intense interest to scholars.

Major civilizations[edit]

During the pre-Columbian period, many city-states, kingdoms, and empires competed with one another for power and prestige. Ancient Mexico can be said to have produced five major civilizations: the Olmec, Maya, Teotihuacan, Toltec, and Aztec. Unlike other indigenous Mexican societies, these civilizations (except the politically fragmented Maya) extended their political and cultural reach across Mexico and beyond.

They consolidated power and exercised influence in trade, art, politics, technology, and religion. Over 3,000 years, other regional powers made economic and political alliances with them; many made war on them. But almost all found themselves within their spheres of influence.

Olmecs (1500–400 BCE)[edit]

The Olmec first appeared along the Atlantic coast (in what is now the state of Tabasco) in the period 1500–900 BCE. The Olmecs were the first Mesoamerican culture to produce an identifiable artistic and cultural style and may also have been the society that invented writing in Mesoamerica. By the Middle Preclassic Period (900–300 BCE), Olmec artistic styles had been adopted as far away as the Valley of Mexico and Costa Rica.

Maya[edit]

Maya cultural characteristics, such as the rise of the ahau, or king, can be traced from 300 BCE onward. During the centuries preceding the classical period, Maya kingdoms stretched from the Pacific coasts of southern Mexico and Guatemala to the northern Yucatán Peninsula. The egalitarian Maya society of pre-royal centuries gradually led to a society controlled by a wealthy elite that began building large ceremonial temples and complexes. The earliest known long-count date, 199 AD, heralds the classic period, during which the Maya kingdoms supported a population numbering in the millions. Tikal, the largest of the kingdoms, alone had 500,000 inhabitants, though the average population of a kingdom was much smaller—somewhere under 50,000 people.

Teotihuacan[edit]

Teotihuacan is an enormous archaeological site in the Basin of Mexico, containing some of the largest pyramidal structures built in the pre-Columbian Americas. Apart from the pyramidal structures, Teotihuacan is also known for its large residential complexes, the Avenue of the Dead, and numerous colorful, well-preserved murals. Additionally, Teotihuacan produced a thin orange pottery style that spread through Mesoamerica.[11]

The city is thought to have been established around 100 BCE and continued to be built until about 250 CE.[12] The city may have lasted until sometime between the 7th and 8th centuries CE. At its zenith, perhaps in the first half of the 1st millennium CE, Teotihuacan was the largest city in the pre-Columbian Americas. At this time, it may have had more than 200,000 inhabitants, placing it among the world's largest cities in this period. Teotihuacan was even home to multi-floor apartment compounds built to accommodate this large population.[12]

The civilization and cultural complex associated with the site is also referred to as Teotihuacan or Teotihuacano. Although it is a subject of debate whether Teotihuacan was the center of a state empire, its influence throughout Mesoamerica is well documented. The ethnicity of the inhabitants of Teotihuacan is also a subject of debate. Possible candidates are the Nahua, Otomi or Totonac ethnic groups. Scholars have also suggested that Teotihuacan was a multiethnic state.

Toltec[edit]

The Toltec culture is an archaeological Mesoamerican culture that dominated a state centered in Tula, Hidalgo, in the early post-classic period of Mesoamerican chronology (ca 800–1000 AD). The later Aztec culture saw the Toltecs as their intellectual and cultural predecessors and described Toltec culture emanating from Tollan (Nahuatl for Tula) as the epitome of civilization; indeed, in the Nahuatl language, the word "Toltec" came to take on the meaning "artisan."

The Aztec oral and pictographic tradition also described the history of the Toltec empire, giving lists of rulers and their exploits. Among modern scholars, it is a matter of debate whether the Aztec narratives of Toltec history should be given credence as descriptions of actual historical events. Other controversies relating to the Toltecs include how best to understand the reasons behind the perceived similarities in architecture and iconography between the archaeological site of Tula and the Maya site of Chichén Itzá – no consensus has emerged yet about the degree or direction of influence between the two sites.

Aztec Empire (1325–1521 AD)[edit]

The Nahua people began to enter central Mexico in the 6th century AD. By the 12th century, they had established their center at Azcapotzalco, the city of the Tepanecs.

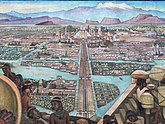

The Mexica people arrived in the Valley of Mexico in 1248 AD. They had migrated from the deserts north of the Rio Grande [citation needed] over a period traditionally said to have been 100 years. They may have thought of themselves as the heirs to the prestigious civilizations that had preceded them.[citation needed] What the Aztecs initially lacked in political power, they made up for with ambition and military skill. In 1325, they established the biggest city in the world, Tenochtitlan.

Aztec religion was based on the belief in the continual need for regular offerings of human blood to keep their deities beneficent; to meet this need, the Aztecs sacrificed thousands of people. This belief is thought to have been common throughout the Nahuatl people. To acquire captives in times of peace, the Aztecs resorted to ritual warfare called flower war. The Tlaxcalteca, among other Nahuatl nations, were forced into such wars.

In 1428, the Aztecs led a war against their rulers from the city of Azcapotzalco, which had subjugated most of the Valley of Mexico's peoples. The revolt was successful, and the Aztecs became central Mexico's rulers as the Triple Alliance leaders. The alliance was composed of the city-states of Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan.

At their peak, 350,000 Aztecs presided over a wealthy tribute empire comprising 10 million people, almost half of Mexico's estimated population of 24 million. Their empire stretched from ocean to ocean and extended into Central America. The westward expansion of the empire was halted by a devastating military defeat at the hands of the Purepecha (who possessed weapons made of copper). The empire relied upon a system of taxation (of goods and services), which was collected through an elaborate bureaucracy of tax collectors, courts, civil servants, and local officials who were installed as loyalists to the Triple Alliance.

By 1519, the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, the site of modern-day Mexico City, was one of the largest cities in the world, with an estimated population between 200,000 and 300,000.[14]

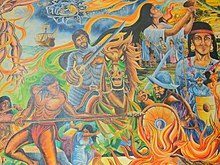

Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire[edit]

A phase of inland expeditions and conquest followed the first mainland explorations. The Spanish crown extended the Reconquista effort, completed in Spain in 1492, to non-Catholic people in new territories. In 1502, on the coast of present-day Colombia, near the Gulf of Urabá, Spanish explorers led by Vasco Núñez de Balboa explored and conquered the area near the Atrato River.[15] The conquest was of the Chibcha-speaking nations, mainly the Muisca and Tairona indigenous people that lived here. The Spanish founded San Sebastian de Uraba in 1509—abandoned within the year, and in 1510, the first permanent Spanish mainland settlement in America, Santa María la Antigua del Darién.[15]

The first Europeans to arrive in modern-day Mexico were the survivors of a Spanish shipwreck in 1511. Only two survived, Gerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero, until further contact was made with Spanish explorers years later. On 8 February 1517, an expedition led by Francisco Hernández de Córdoba left the harbor of Santiago de Cuba to explore the shores of southern Mexico. During this expedition, many of Hernández's men were killed, most during a battle near the town of Champotón against a Maya army. Hernández himself was injured and died a few days shortly after his return to Cuba. This was the Europeans' first encounter with a civilization in the Americas with buildings and complex social organizations that they recognized as comparable to the Old World. Hernán Cortés led a new expedition to Mexico, landing ashore at present-day Veracruz on 22 April 1519, a date which marks the beginning of 300 years of Spanish hegemony over the region.

The 'Spanish conquest of Mexico denotes the conquest of the central region of Mesoamerica, where the Aztec Empire was based. The fall of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan in 1521 was a decisive event, but the conquest of other regions of Mexico, such as Yucatán, extended long after the Spaniards consolidated control of central Mexico. The Spanish conquest of Yucatán was a much longer campaign, from 1551 to 1697, against the Maya peoples of the Maya civilization in the Yucatán Peninsula of present-day Mexico and northern Central America.

Smallpox (Variola major and Variola minor) began to spread in Mesoamerica immediately after the arrival of Europeans. The indigenous peoples, who had no immunity to it, eventually died in the millions.[16] A third of all the natives of the Valley of Mexico succumbed to it within six months of the Spaniards' arrival.

Tenochtitlan was almost destroyed by fire and cannon fire. Cortés imprisoned the royal families of the valley. To prevent another revolt, he tortured and killed Cuauhtémoc, the last Aztec Emperor; Coanacoch, the King of Texcoco, and Tetlepanquetzal, King of Tlacopan.

The small contingent of Spaniards controlled central Mexico through existing indigenous rulers of individual political states (altepetl), who maintained their status as nobles in the post-conquest era if they cooperated with Spanish rule. Cortés immediately banned human sacrifice throughout the conquered empire. In 1524, he requested the Spanish king to send friars from the mendicant orders, particularly the Franciscan, Dominican, and Augustinian, to convert the indigenous to Christianity. This has often been called the "spiritual conquest of Mexico."[17] Christian evangelization began in the early 1520s and continued into the 1560s. Many of the mendicant friars, especially the Franciscans and Dominicans, learned the native languages and recorded aspects of native culture.[18] The Spanish colonizers introduced the encomienda system of forced labor. Indigenous communities were pressed for labor and tribute but were not enslaved. Their rulers remained indigenous elites who retained their status under colonial rule and were useful intermediaries.[19] The Spanish also used forced labor, often outright slavery, in mining.[20]

New Spain[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

The capture of Tenochtitlan marked the beginning of a 300-year colonial period, during which Mexico was known as "New Spain" and ruled by a viceroy in the name of the Spanish monarch. Colonial Mexico had key elements to attract Spanish immigrants: dense and politically complex indigenous populations that could be compelled to work and huge mineral wealth, especially major silver deposits. The Viceroyalty of Peru shared these elements, so New Spain and Peru were the seats of Spanish power and the source of its wealth until other viceroyalties were created in Spanish South America in the late 18th century. This wealth made Spain a dominant power in Europe. Spain's silver mining and crown mints created high-quality coins, the currency of Spanish America, the silver peso or Spanish dollar that became a global currency.

Spain did not bring all areas of the Aztec Empire under its control. After the fall of Tenochtitlan in 1521, it took decades of warfare to subdue the rest of Mesoamerica, particularly the Mayan regions of southern New Spain, and into what is now Central America. Spanish conquests of south Mesoamerica's Zapotec and Mixtec regions were relatively rapid.

Outside the zone of settled Mesoamerican civilizations were semi-nomadic northern peoples who fought fiercely against the Spaniards and their indigenous allies, such as the Tlaxcalans, in the Chichimeca War (1550–1590). The northern indigenous populations had gained mobility via the horses that Spaniards had imported to the New World. The region was important to the Spanish because of its rich silver deposits. The Spanish mining settlements and trunk lines to Mexico City needed to be made safe for supplies to move north and silver to move south to central Mexico.

The most important source of wealth was indigenous tribute and compelled labor, mobilized in the first years after the conquest of central Mexico through the encomienda. The encomienda was a grant of the labor of a particular indigenous settlement to an individual Spanish and his heirs. Spaniards were the recipients of traditional indigenous products that had been rendered in tribute to their local lords and the Aztec empire. The earliest holders of encomiendas, the encomenderos, were the conquerors involved in the campaign leading to the fall of Tenochtitlan and later their heirs and people with influence but not conquerors. Forced labor could be directed toward developing land and industry. Land was a secondary source of wealth during this immediate conquest period. Where indigenous labor was absent or needed supplementing, the Spanish brought enslaved people, often as skilled laborers or artisans. [citation needed]

Europeans, Africans, and indigenous intermixed, creating a mixed-race casta population in a process known as mestizaje. Mestizos, people of mixed European-indigenous ancestry, constitute most of Mexico's population.[21]

Colonial period (1521–1821)[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

Colonial Mexico was part of the Spanish Empire and was administered by the Viceroyalty of New Spain. New Spain became the largest and most important Spanish colony. During the 16th century, Spain focused on conquering areas with dense populations that had produced pre-Columbian civilizations. These populations were a labor force with a history of tribute and a population to convert to Christianity. Territories populated by nomadic peoples were harder to conquer. Although the Spanish explored much of North America, seeking the fabled "El Dorado," they made no concerted effort to settle the northern desert regions in what is now the United States until the end of the 16th century (Santa Fe, 1598).

Colonial law with native origins but with Spanish historical precedents was introduced, creating a balance between local jurisdiction (the Cabildos) and the Crown. The administration was based on a racial separation of the population among the Republics of Spaniards, Natives, and Mestizos, autonomous and directly dependent on the king.

The population of New Spain was divided into four main groups or classes. The group a person belonged to was determined by racial background and birthplace. The most powerful group was the Spaniards, people born in Spain and sent across the Atlantic to rule the colony. Only Spaniards could hold high-level jobs in the colonial government. The second group called criollos, were people of Spanish background but born in Mexico. Many criollos were prosperous landowners and merchants. Even the wealthiest Creoles had little say in government. The third group, the mestizos ("mixed"), were people who had some Spanish ancestors and some Native ancestors. Mestizos had a lower position and were looked down upon by the Spaniards and the Creoles. The poorest, most marginalized group in New Spain was the Natives, descendants of pre-Columbian peoples. They had less power and endured harsher conditions than other groups. Natives were forced to work as laborers on the ranches and farms (called haciendas) of the Spaniards and Creoles. In addition to the four main groups, some Africans were in colonial Mexico. These Africans were imported as enslaved people and shared the low status of the Natives. They made up about 4% to 5% of the population, and their mixed-race descendants, called mulattoes, eventually grew to represent about 9%. From an economic point of view, New Spain was administered principally for the benefit of the Empire and its military and defensive efforts. Mexico provided more than half of the Empire's taxes and supported the administration of all North and Central America. Competition with the metropolis was discouraged; for example, cultivation of grapes and olives, introduced by Cortés himself, was banned out of fear that these crops would compete with Spain's.[22]

To protect the country from the attacks by English, French, and Dutch pirates, as well as the Crown's revenue, only two ports were open to foreign trade—Veracruz on the Atlantic, connecting through Havana at Cuba to Spain;[23][24] and Acapulco, connecting through Manila at the Philippines, on the Pacific, to Asia.[25][26]

Education was encouraged by the Crown: Mexico boasts the first primary school (Texcoco, 1523), the first university, the University of Mexico (1551) and the first printing press (1524) of the Americas. Indigenous languages were studied mainly by the religious orders during the first centuries and became official languages in the so-called Republic of Natives, only to be outlawed and ignored after independence by the prevailing Spanish-speaking creoles.

Mexico produced important cultural achievements during the colonial period, such as the literature of seventeenth-century nuns, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, and Ruiz de Alarcón, as well as cathedrals, civil monuments, forts and colonial cities such as Puebla, Mexico City, Querétaro, Zacatecas and others, today part of Unesco's World Heritage.

The syncretism between indigenous and Spanish cultures gave rise to many modern Mexican staples like tequila (since the 16th century), mariachi (18th), jarabe (17th), charros (17th) and Mexican cuisine.

American-born Spaniards (creoles), mixed-race castas, and Natives often disagreed, but all resented the small minority of Iberian-born Spaniards monopolizing political power. By the early 1800s, many American-born Spaniards believed that Mexico should become independent of Spain, following the example of the United States. The man who touched off the revolt against Spain was the Catholic priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla. He is remembered today as the Father of the Nation.[27]

Independence era (1808–1829)[edit]

This period was marked by unanticipated events that upended the three hundred years of Spanish colonial rule. The colony went from rule by the legitimate Spanish monarch and his appointed viceroy to an illegitimate monarch and viceroy put in place by a coup. Later, Mexico would see the return of the Spanish monarchy and a later stalemate with insurgent guerrilla forces.

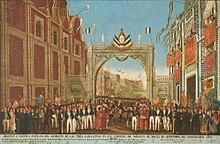

Events in Spain during the Peninsular War and the Trienio Liberal upended the situation in New Spain. After Spanish military officers overthrew the absolutist monarch Ferdinand VII and returned to the liberal Spanish Constitution of 1812, conservatives in New Spain who had staunchly defended the Spanish monarchy changed course and pursued independence. Royalist army officer Agustín de Iturbide became an advocate of independence and persuaded insurgent leader Vicente Guerrero to join in a coalition, forming the Army of the Three Guarantees. Within six months of that joint venture, royal rule in New Spain collapsed, and independence was achieved.

The constitutional monarchy envisioned with a European royal on the throne did not pass; Creole military officer Iturbide became Emperor Agustín I. His increasingly autocratic rule dismayed many, and a coup overthrew him in 1823. Mexico became a federated republic and promulgated a constitution in 1824. While General Guadalupe Victoria became the first president, serving his entire term, the presidential transition became less of an electoral event and more of one by force of arms. Insurgent general and prominent Liberal politician Vicente Guerrero was briefly president in 1829, then deposed and judicially murdered by his Conservative opponents.

Mexico experienced political instability and violence in the first years after independence, with more to come until the late nineteenth century. The presidency changed hands 75 times in the next half-century.[28] The new republic's situation did not promote economic growth or development, with the silver mines damaged, trade disrupted, and lingering violence.[29][30] Although British merchants established a network of merchant houses in the major cities the situation was bleak. "Trade was stagnant. Imports did not pay, contraband drove prices down, private and public debts went unpaid, merchants suffered all manner of injustices and operated at the mercy of weak and corruptible governments."[31]

Prelude to independence[edit]

Inspired by the American and French Revolutions, Mexican insurgents saw an opportunity for independence in 1808 when Napoleon invaded Spain, and the Spanish king Charles IV was forced to surrender. Napoleon placed his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the Spanish throne. In New Spain, viceroy José de Iturrigaray proposed to provisionally form an autonomous government, with the support of American-born Spaniards on the city council of Mexico City. Peninsular-born Spaniards in the colony saw this as undermining their power, and Gabriel J. de Yermo led a coup against the viceroy, arresting him in September 1808. Spanish conspirators named Spanish military officer Pedro de Garibay viceroy. His tenure was brief, from September 1808 until July 1809, when he was replaced by Francisco Javier de Lizana y Beaumont, whose tenure was also short until the arrival of viceroy Francisco Javier Venegas from Spain. Two days after he entered Mexico City on 14 September 1810, Father Miguel Hidalgo called to arms in the village of Hidalgo. France and the Spanish king invaded Spain, was deposed, and Joseph Bonaparte imposed. New Spain's viceroy José de Iturrigaray, sympathetic to Creoles, sought to create a legitimate government but was overthrown by powerful Peninsular Spaniards; hard-line Spaniards clamped down on any notion of Mexican autonomy. Creoles who had hoped that there was a path to Mexican autonomy, perhaps within the Spanish Empire, now saw that their only path was independence through rebellion.

War of Independence, 1810–1821[edit]

In northern Mexico, Father Miguel Hidalgo, creole militia officer Ignacio Allende, and Juan Aldama met to plot rebellion. When the plot was discovered in September 1810, Hidalgo called his parishioners to arms in the village of Dolores, touching off a massive rebellion in the region of the Bajío. This event of 16 September 1810 is now called the "Cry of Dolores," and is now celebrated as Independence Day. Shouting, "Independence and death to the Spaniards!" Some 80,000 poorly organized and armed villagers formed a force that initially rampaged unstopped in Bajío. The viceroy was slow to respond, but once the royal army engaged the untrained, poorly armed and led mass, they routed the insurgents in the Battle of Calderón Bridge. Hidalgo was captured, defrocked as a priest, and executed.[32]

Another priest, José María Morelos, took over and was more successful in his quest for republicanism and independence. Spain's monarchy was restored in 1814 after Napoleon's defeat, and it fought back and executed Morelos in 1815. The scattered insurgents formed guerrilla bands. In 1820, the Spanish royal army brigadier Agustín de Iturbide changed sides and proposed independence, issuing the Plan of Iguala. Iturbide persuaded insurgent leader Vicente Guerrero to join this new push for independence. General Isidoro Montes de Oca, with few and poorly armed insurgents, inflicted a real defeat on the royalist Gabriel from Armijo, and they also got enough equipment to arm 1,800 rebels properly. He stood out for his courage in the Siege of Acapulco in 1813, under the orders of General José María Morelos y Pavón.[33] Isidoro inflicted defeat on the royalist army from Spain. Impressed, Itubide joined forces with Guerrero and demanded independence, a constitutional monarchy in Mexico, the continued religious monopoly for the Catholic Church, and equality for Spaniards and those born in Mexico. Royalists who now followed Iturbide's change of sides and insurgents formed the Army of the Three Guarantees. Within six months, the new army controlled all but the ports of Veracruz and Acapulco. On September 27, 1821, Iturbide and the last viceroy, Juan O'Donojú, signed the Treaty of Córdoba whereby Spain granted the demands. O'Donojú had been operating under instructions issued months before the latest events. Spain refused to recognize Mexico's independence formally, and the situation became even more complicated by O'Donojú's death in October 1821.[34]

First Mexican Empire[edit]

When Mexico achieved its independence, the southern portion of New Spain became independent as well, as a result of the Treaty of Córdoba, so Central America, present-day Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and part of Chiapas were incorporated into the Mexican Empire. Although Mexico now had its own government, there was no revolutionary social or economic change. The formal, legal racial distinctions were abolished, but power remained in the hands of white elites. The monarchy was the form of government Mexicans knew, and it is unsurprising that they chose it initially. The political power of the royal government was transferred to the military. The Roman Catholic Church was the other pillar of institutional rule. Both the army and the church lost personnel while establishing the new regime. An index of the fall in the economy was the decrease in revenues to the church via the tithe, a tax on agricultural output. Mining, especially, was hard hit. It had been the motor of the colonial economy, but there was considerable fighting during the war of independence in Zacatecas and Guanajuato, the two most important silver mining sites.[35] Despite Viceroy O'Donojú's signing the Treaty of Córdoba giving Mexico independence, the Spanish government did not recognize it as legitimate and claimed sovereignty over Mexico.

Spain set in motion events that brought Iturbide, the son of a provincial merchant, to be the Emperor of Mexico. With Spain's rejection of the treaty and no European royal taking up the offer of being Mexico's monarch, many Creoles now decided that having a Mexican as its monarch was acceptable. A local army garrison proclaimed Iturbide emperor. Since the church refused to crown him, the president of the constituent Congress did so on 21 July 1822. His long-term rule was doomed. He did not have the respect of the Mexican nobility. Republicans sought that form of government rather than a monarchy. The emperor set up all the trappings of a monarchy with a court. Iturbide became increasingly dictatorial and shut down Congress. Worried that a young colonel, Antonio López de Santa Anna, would raise a rebellion, the emperor relieved him of his command. Rather than obeying the order, Santa Anna proclaimed a republic and hastily called for the reconvening of Congress. Four days later, he walked back to his republicanism and called for the removal of the emperor in the Plan of Casa Mata. Santa Anna secured the support of insurgent general Guadalupe Victoria. The army signed on to the plan, and the emperor surrendered on March 19, 1823.[36]

First Mexican Republic[edit]

Those who overthrew the emperor then nullified the Plan of Iguala, which had called for a constitutional monarchy and the Treaty of Córdoba, freeing them to choose a new government. It was to be a federal republic, and on 4 October 1824, the United Mexican States (Estados Unidos Mexicanos) was established. The new constitution was partly modeled on the constitution of the United States. It guaranteed basic human rights and defined Mexico as a representative federal republic in which the responsibilities of government were divided between a central government and several smaller units called states. It also defined Catholicism as the official and only religion of the republic. Central America did not join the federated republic and took a separate political path from 1 July 1823.

Mexico's establishment of a new form of government did not bring stability. The civilian government contested political power from the army and the Roman Catholic Church. The military and the church retained special privileges called fueros. General Guadalupe Victoria was followed in office by General Vicente Guerrero, gaining the position through a coup after losing the 1828 elections. The Conservative Party saw an opportunity to seize control and led a counter-coup under General Anastasio Bustamante, who served as president from 1830 to 1832, and again from 1837 to 1841.

The Age of Santa Anna (1829–1854)[edit]

Political instability[edit]

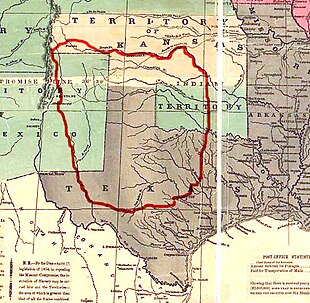

In much of Spanish America, soon after its independence, military strongmen or caudillos dominated politics, and this period is often called "The Age of Caudillismo." In Mexico, from the late 1820s to the mid-1850s, the period is often called the "Age of Santa Anna," named for the general and politician, Antonio López de Santa Anna. Liberals (federalists) asked Santa Anna to overthrow the conservative President Anastasio Bustamante. After he did, he declared General Manuel Gómez Pedraza (who won the election of 1828) president. Elections were held after that, and Santa Anna took office in 1832. He served as president for 11 non-consecutive terms.[37] Constantly changing his political beliefs, in 1834 Santa Anna abolished the federal constitution, causing insurgencies in the southeastern state of Yucatán and the northernmost portion of the northern state of Coahuila y Tejas. Both areas sought independence from the central government. Negotiations and the presence of Santa Anna's army caused Yucatán to recognize Mexican sovereignty. Then, Santa Anna's army turned to the northern rebellion.

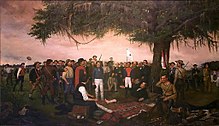

The inhabitants of Tejas declared the Republic of Texas independent from Mexico on 2 March 1836 at Washington-on-the-Brazos. They called themselves Texans and were led mainly by recent Anglo-American settlers. At the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836, Texan militiamen defeated the Mexican army and captured General Santa Anna. The Mexican government refused to recognize Texas' independence.

Comanche conflict[edit]

The northern states grew increasingly isolated, economically and politically, due to prolonged Comanche raids and attacks. The local peoples had not recognized the Spanish Empire's claims to the region, nor did they when Mexico became an independent nation. Mexico attempted to convince its citizens to settle in the region but with few takers. Mexico negotiated a contract with Anglo-Americans to settle in the area, hoping and expecting that they would do so in Comanche territory, the Comancheria. In the 1820s, when the United States began to influence the region, New Mexico had already questioned its loyalty to Mexico. By the time of the Mexican–American War, the Comanches had raided and pillaged large portions of northern Mexico, resulting in sustained impoverishment, political fragmentation, and general frustration at the inability—or unwillingness—of the Mexican government to discipline the Comanches.[38]

In addition to Comanche raids, the First Republic's northern border was plagued with attacks on its northern border from the Apache people, who were supplied with guns by American merchants.[39] Goods including guns and shoes were sold to the Apache, the latter being discovered by Mexican forces when they found traditional Apache trails with American shoe prints instead of moccasin prints.[39]

Texas Independence[edit]

After the Mexican War of Independence, the Mexican government, to populate its northern territories, awarded extensive land grants in Coahuila y Tejas to thousands of families from the United States so that the settlers convert to Catholicism and become Mexican citizens. The Mexican government also forbade the importation of enslaved people. These conditions were largely ignored.[40]

A key factor in the government's decision to allow those settlers was the belief that they would (a) protect northern Mexico from Comanche attacks and (b) buffer the northern states against US westward expansion. The policy failed on both counts: the Americans tended to settle far from the Comanche raiding zones and used the Mexican government's failure to suppress the raids as a pretext for declaring independence.[38]

The Texas Revolution or Texas War of Independence was a military conflict between Mexico and settlers in the Texas portion of the Mexican state Coahuila y Tejas. The war lasted from October 2, 1835, to April 21, 1836. However, war at sea between Mexico and Texas continued into the 1840s. The animosity between the Mexican government and the American settlers in Texas, as well as many Texas residents of Mexican ancestry, intensified with the Siete Leyes of 1835 when Mexican President and General Antonio López de Santa Anna abolished the federal Constitution of 1824 and proclaimed the more centralizing 1835 constitution in its place.

War began in Texas on October 2, 1835, with the Battle of Gonzales. Early Texian Army successes at La Bahia and San Antonio were soon met with crushing defeat at the same locations a few months later. The war ended at the Battle of San Jacinto, where General Sam Houston led the Texian Army to victory over a portion of the Mexican Army under Santa Anna, who was captured soon after the battle. The war's end resulted in the creation of the Republic of Texas in 1836. In 1845, the U.S. Congress ratified Texas's petition for statehood.

Mexican-American War (1846–1848)[edit]

In response to a Mexican attack on a U.S. army detachment in disputed territory, the U.S. Congress declared war on May 13, 1846; Mexico followed suit on May 23. The Mexican–American War took place in two theaters: the Western (aimed at California) and Central Mexico (aimed at capturing Mexico City) campaigns.

In March 1847, U.S. President James K. Polk sent an army of 12,000 soldiers under General Winfield Scott to Veracruz. The 70 ships of the invading forces arrived at the city on 7 March and began a naval bombardment. After landing, Scott started the Siege of Veracruz.[41] The city, at that time still walled, was defended by Mexican General Juan Morales with 3,400 men. Veracruz replied as best it could with artillery to the bombardment from land and sea, but the city walls were reduced. After 12 days, the Mexicans surrendered. Scott marched west with 8,500 men, while Santa Anna was entrenched with artillery and 12,000 troops on the main road halfway to Mexico City. Santa Anna was outflanked and routed at the Battle of Cerro Gordo.

Scott pushed on to Puebla, then Mexico's second-largest city, which capitulated without resistance on 1 May—the citizens were hostile to Santa Anna. After the Battle of Chapultepec (13 September 1847), Mexico City was occupied; Scott became its military governor. Many other parts of Mexico were also occupied. Some Mexican units fought with distinction: a group of six Military College cadets (now considered Mexican national heroes) who fought to the death defending their college during the Battle of Chapultepec.

The war ended with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which stipulated that (1) Mexico must sell its northern territories to the US for US$15 million; (2) the US would give full citizenship and voting rights and protect the property rights of Mexicans living in the ceded territories; and (3) the US would assume $3.25 million in debt owed by Mexico to Americans.[42] Mexico's defeat has been attributed to its problematic internal situation, one of disunity and disorganization.

End of Santa Anna's rule[edit]

Despite Santa Anna's role in the Mexican–American War catastrophe, he returned to power again. When the U.S. ambitioned an easier railroad route to California south of the Gila River, Santa Anna sold the Gadsden Strip to the US for $10 million in the Gadsden Purchase in 1853. This loss of more territory provoked outrage among Mexicans, but Santa Anna claimed that he needed money to rebuild the army from the war. In the end, he kept or squandered most of it.[43] Liberals finally coalesced and successfully rebelled against his regime, promulgating the Plan of Ayutla in 1854 and forcing Santa Anna into exile.[44][45] Liberals came to power and began enacting reforms they had long envisioned.

Struggle between liberals and conservatives, 1855–1876[edit]

Liberals ousted conservative Santa Anna in the Plan of Ayutla and sought to implement liberal reforms in a series of separate laws, then in a new constitution, which incorporated them. Mexico experienced civil war and foreign intervention that established a monarchy with the support of Mexican conservatives. The fall of the empire of Maximilian of Mexico and his execution in 1867 ushered in a period of relative peace but economic stagnation during the Restored Republic. In general, the history writing in this era has characterized the liberals as forging a new, modern nation and conservatives as reactionary opponents of that vision. However, more recent analyses are more nuanced.[46]

La Reforma began with the final overthrow of Santa Anna in the Plan of Ayutla in 1855. Moderate Liberal Ignacio Comonfort became president. The Moderados tried to find a middle ground between the nation's liberals and conservatives. There is less consensus about the ending point of the Reforma.[47] Common dates are 1861, after the liberal victory in the Reform War; 1867, after the republican victory over the French intervention in Mexico; and 1876 when Porfirio Díaz overthrew president Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada. Liberalism dominated Mexico as an intellectual force into the 20th century. Liberals championed reform and supported republicanism, capitalism, and individualism; they fought to reduce the Church's roles in education, land ownership and politics.[47] Also importantly, liberals sought to end the special status of indigenous communities by ending their corporate ownership of land.

Liberal Colonel Ignacio Comonfort became president in 1855. Comonfort was a moderate who tried and failed to maintain an uncertain coalition of radical and moderate liberals. Radical liberals drafted the Constitution of 1857, which decreased the power of the executive, incorporated the laws of the Reform, and curtailed traditional powers of the Catholic Church.[48] It granted religious freedom, stating only that the Catholic Church was the favored faith. The anti-clerical liberals scored a major victory with the constitution's ratification because it weakened the Church and enfranchised non-property-owning men. The constitution was opposed by the army, the clergy, and the other conservatives, as well as moderate liberals such as Comonfort. With the Plan of Tacubaya in December 1857, conservative General Félix Zuloaga led a coup in the capital in January 1858, creating a parallel government in Mexico City. Comonfort resigned from the presidency and was succeeded by the President of the Supreme Court, Benito Juárez, who became President of the Republic, leading Mexican liberals.[48]

The revolt led to the War of Reform (1857–1861), which grew increasingly bloody as it progressed and polarized the nation's politics. Many Moderates, convinced that the Church's political power had to be curbed, came over to the side of the Liberals. For some time, the Liberals and Conservatives simultaneously administered separate governments, the Conservatives from Mexico City and the Liberals from Veracruz. The war ended with a Liberal victory, and liberal President Benito Juárez moved his administration to Mexico City.

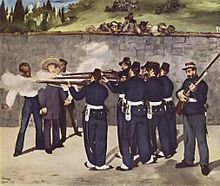

In 1862, the country was invaded by France sought to collect debts that the Juárez government had defaulted on. Still, the larger purpose was to install a ruler under French control. Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Austria was installed as Emperor Maximilian I of Mexico, with support from the Catholic Church, conservative elements of the upper class, and some indigenous communities. Although the French suffered an initial defeat (the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862, now commemorated as the Cinco de Mayo holiday), the French eventually defeated the Mexican army and set Maximilian on the throne. The Mexican-French monarchy set up administration in Mexico City, governing from the National Palace.[49] Maximilian has been praised by some historians for his liberal reforms, his desire to help the people of Mexico, and his refusal to desert his loyal followers. Some accused him of exploiting the nation's resources for themselves and their allies, including favoring the plans of Napoleon III to exploit the mines in the northwest of the country and to grow cotton.[49]

Maximilian favored establishing a limited monarchy to share power with a democratically elected congress. This was too liberal for conservatives, while liberals refused to accept any monarch, considering the republican government of Benito Juárez as legitimate. This left Maximilian with few allies within Mexico. Meanwhile, Juárez continued to be recognized by the United States, which was engaged in its Civil War (1861–65) and at that juncture was in no position to aid Juárez directly against the French intervention until 1865. France never made a profit in Mexico, and its Mexican expedition grew increasingly unpopular. After the US Civil War, the US demanded the withdrawal of French troops from Mexico. Napoleon III quietly complied. In mid-1867, despite repeated Imperial losses in battle to the Republican Army and ever-decreasing support from Napoleon III, Maximilian chose to remain in Mexico rather than return to Europe. He was captured and executed along with two Mexican supporters. Juárez remained in office until he died in 1872. In 1867, with the defeat of the monarchy and the execution of Emperor Maximilian, the republic was restored, and Juárez was reelected. He continued to implement his reforms. In 1871, he was elected a second time, much to the dismay of his opponents within the Liberal party, who considered reelection somewhat undemocratic. Juárez died the following year and was succeeded by Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada. Part of Juárez's reforms included fully secularizing the country. The Catholic Church was barred from owning property aside from houses of worship and monasteries, and education and marriage were put in the hands of the state.

Porfiriato (1876–1910)[edit]

The rule of Porfirio Díaz (1876–1911) was dedicated to the rule by law, suppression of violence and modernization of the country. Diaz was a military commander on the liberal side in the 1860s who seized power in a coup in 1876, established a dictatorship, and ruled in collaboration with the landed oligarchy. He maintained good relations with the United States and Great Britain, which led to a sharp rise in foreign direct investment, especially in mining. The general standard of living rose steadily. He adhered to a coarse social laissez-faire doctrine that primarily benefited the already privileged social classes. Diaz was overthrown by the Mexican Revolution of 1911 and died in exile.[50]

This period of relative prosperity is known as the Porfiriato. As traditional ways were challenged, urban Mexicans debated national identity, the rejection of indigenous cultures, the new passion for French culture once the French were ousted from Mexico, and the challenge of creating a modern nation-state through industrialization and scientific development.[51] Cities were rebuilt with modernizing architects favoring the latest Western European styles, especially the Beaux-Arts style, to symbolize the break with the past. A highly visible exemplar was the Federal Legislative Palace, built 1897–1910.[52]

Díaz remained in power by rigging elections and censoring the press. Rivals were destroyed, and popular generals were moved to new areas so they could not build a permanent support base. Banditry on roads leading to major cities was largely suppressed by the "Rurales," a police force controlled by Díaz, created during a process of military modernization. Banditry remained a major threat in more remote areas because the Rurales comprised fewer than 1000 men.[53] Díaz was an astute military leader and liberal politician who built a national base of supporters. He maintained a stable relationship with the Catholic Church by avoiding enforcing constitutional anticlerical laws. The country's infrastructure was greatly improved through increased foreign investment from Britain and the US and a strong, participatory central government.[54] Increased tax revenue and better administration improved public safety, public health, railways, mining, industry, foreign trade, and national finances. After a half-century of stagnation, where per capita income was merely a tenth of the developed nations such as Britain and the US, the Mexican economy took off during the Porfiriato, growing at an annual rate of 2.3% (1877 to 1910), which was high by world standards.[54]

Order, progress, and dictatorship[edit]

Díaz reduced the Army from 30,000 to under 20,000 men, which resulted in a smaller percentage of the national budget being committed to the military. The army was modernized, well-trained, and equipped with the latest technology. The Army was top-heavy with 5,000 officers, many of them elderly but politically well-connected veterans of the wars of the 1860s.[55]

The political skills that Díaz used so effectively before 1900 faded, as he and his closest advisers were less open to negotiations with younger leaders. His announcement in 1908 that he would retire in 1911 unleashed a widespread feeling that Díaz was on the way out and that new coalitions had to be built. He nevertheless ran for reelection and in a show of U.S. support, Díaz and William Taft planned a summit in El Paso, Texas, and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, for October 16, 1909, a historic first meeting between a Mexican and a U.S. president and also the first time an American president would cross the border into Mexico.[56] The meeting focused attention on the disputed Chamizal strip and resulted in assassination threats and other serious security concerns.[56] At the meeting, Díaz told John Hays Hammond, "Since I am responsible for bringing several billion dollars in foreign investments into my country, I think I should continue in my position until a competent successor is found."[57] Díaz was re-elected after a highly controversial election, but he was overthrown in 1911 and forced into exile in France after Army units rebelled.

Economy[edit]

Fiscal stability was achieved by José Yves Limantour, Secretary of Finance of Mexico from 1893 until 1910. He was the leader of the well-educated technocrats known as Científicos, who were committed to modernity and sound finance. Limantour expanded foreign investment, supported free trade, balanced the budget for the first time, and generated a budget surplus by 1894. However, he could not halt the rising cost of food, which alienated the poor.[58]

The American Panic of 1907 was an economic downturn that caused a sudden drop in demand for Mexican copper, silver, gold, zinc, and other metals. Mexico cut its imports of horses and mules, mining machinery, and railroad supplies. The result was an economic depression in Mexico in 1908–1909 that soured optimism and raised discontent with the Díaz regime.[59] Mexico was vulnerable to external shocks because of its weak banking system.[citation needed]

Mexico had few factories by 1880, but industrialization took hold in the Northeast, especially in Monterrey. Factories produced machinery, textiles, and beer, while smelters processed ores. Convenient rail links with the nearby US gave local entrepreneurs from seven wealthy merchant families a competitive advantage over more distant cities. New federal laws in 1884 and 1887 allowed corporations to be more flexible. By the 1920s, American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO), an American firm controlled by the Guggenheim family, had invested over 20 million pesos and employed nearly 2,000 workers smelting copper and making wire to meet the demand for electrical wiring in the US and Mexico.[60]

Education[edit]

The modernizers insisted that public schools and secular education should replace religious schooling by the Catholic Church.[61] They reformed elementary schools by mandating uniformity, secularization, and rationality. These reforms were consistent with international trends in teaching methods. To break the traditional peasant habits that were seen to hinder industrialization, reforms emphasized children's punctuality, assiduity, and health.[62] In 1910, the National University was opened.

Rural unrest[edit]

Historian John Tutino examines the impact of the Porfiriato in the highland basins south of Mexico City, which became the Zapatista heartland during the Revolution. Population growth, railways, and concentration of land in a few families generated a commercial expansion that undercut the traditional powers of the villagers. Young men felt insecure about the patriarchal roles they had expected to fill. Initially, this anxiety manifested as violence within families and communities. But, after the defeat of Díaz in 1910, villagers expressed their rage in revolutionary assaults on local elites who had profited most from the Porfiriato. The young men were radicalized as they fought for their traditional roles regarding land, community, and patriarchy.[63]

Revolution of 1910–1920[edit]

The Mexican Revolution is a broad term for political and social changes in the early 20th century. Most scholars consider it to span the years 1910–1920, from Francisco I. Madero's call for armed rebellion in the Plan of San Luis Potosí until the election of General Álvaro Obregón in December 1920. Foreign powers had important economic and strategic interests in the outcome of power struggles in Mexico, with the United States' involvement in the Mexican Revolution playing an especially significant role.[64] The Revolution grew increasingly broad-based, radical, and violent. Revolutionaries sought far-reaching social and economic reforms by strengthening the state and weakening the conservative forces of the Church, rich landowners, and foreign capitalists.

Some scholars consider the promulgation of the Mexican Constitution of 1917 as the revolution's endpoint. "Economic and social conditions improved under revolutionary policies, so that the new society took shape within a framework of official revolutionary institutions," with the constitution providing that framework.[65] Organized labor gained significant power, as seen in Article 123 of the Constitution of 1917. Land reform in Mexico was enabled by Article 27. Economic nationalism was also enabled by Article 27, restricting ownership of enterprises by foreigners. The Constitution restricted the Catholic Church; implementing the restrictions in the late 1920s resulted in the Cristero War. The Constitution and practice enshrined a ban on the president's re-election. Political succession was achieved in 1929 with the creation of the Partido Nacional Revolucionario (PNR). This political party dominated Mexico's politics for the remainder of the 20th century, now called the Institutional Revolutionary Party.

One major effect of the revolution was the disappearance of the Federal Army in 1914, defeated by revolutionary forces of the various factions in the Mexican Revolution.[66] The Mexican Revolution was based on popular participation. At first, it was based on the peasantry who demanded land, water, and a more representative national government. Wasserman finds that:

Popular participation in the revolution and its aftermath took three forms. First, everyday people, though often in conjunction with elite neighbors, generated local issues such as access to land, taxes, and village autonomy. Second, the popular classes provided soldiers to fight in the revolution. Third, local issues advocated by campesinos and workers framed national discourses on land reform, the role of religion, and many other questions.[67]

Election of 1910 and popular rebellion[edit]

Porfirio Díaz announced in an interview with a US journalist James Creelman that he would not run for president in 1910. This set off a spate of political activity by potential candidates, including Francisco I. Madero, a member of one of Mexico's richest families. Madero was part of the Anti-Reelectionist Party, whose main platform was the end of the Díaz regime. But Díaz reversed his decision to retire and ran again. He created the office of vice president, which could have been a mechanism to ease the presidential transition. But Díaz chose a politically unpalatable running mate, Ramón Corral, over a popular military man, Bernardo Reyes, and a popular civilian Francisco I. Madero. He sent Reyes on a "study mission" to Europe and jailed Madero. Official election results declared that Díaz had won almost unanimously, and Madero received only a few hundred votes. This fraud was too blatant, and riots broke out. Uprisings against Díaz occurred in the fall of 1910, particularly in Mexico's north and the southern state of Morelos. Helping unite opposition forces was a political plan drafted by Madero, the Plan of San Luis Potosí, in which he called on the Mexican people to take up arms and fight against the Díaz government. The rising was set for November 20, 1910. Madero escaped from prison to San Antonio, Texas, where he began preparing to overthrow Díaz—an action today considered the start of the Mexican Revolution. Díaz tried to use the army to suppress the revolts, but most of the ranking generals were old men close to his age, and they did not act swiftly or with sufficient energy to stem the violence. Revolutionary force—led by, among others, Emiliano Zapata in the South, Pancho Villa and Pascual Orozco in the North, and Venustiano Carranza—defeated the Federal Army.

Díaz resigned in May 1911 for the "sake of the nation's peace." The terms of his resignation were spelled out in the Treaty of Ciudad Juárez, but it also called for an interim presidency and new elections to be held. Francisco León de la Barra served as interim president. The Federal Army, although defeated by the northern revolutionaries, was kept intact. Francisco I. Madero, whose 1910 Plan of San Luis Potosí had helped mobilize forces opposed to Díaz, accepted the political settlement. He campaigned in the presidential elections of October 1911, won decisively, and was inaugurated in November 1911.[68]

Madero presidency and its opposition, 1911–1913[edit]

Following the resignation of Díaz and a brief interim presidency of a high-level government official from the Díaz era, Madero was elected president in 1911. The revolutionary leaders had many different objectives; revolutionary figures varied from liberals such as Madero to radicals such as Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa. Consequently, it proved impossible to agree on how to organize the government that emerged from the triumphant first phase of the revolution. This standoff over political principles quickly led to a struggle for government control, a violent conflict that lasted more than ten years.

Counter-revolution and Civil War, 1913–1915[edit]

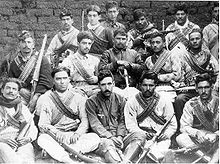

Madero was ousted and killed in February 1913 during a coup d'état now known as the Ten Tragic Days. General Victoriano Huerta, one of Díaz's former generals and a nephew of Díaz, Félix Díaz, plotted with the US ambassador to Mexico, Henry Lane Wilson, to topple Madero and reassert the policies of Díaz. Within a month of the coup, rebellions started spreading in Mexico, most prominently by the governor of the state of Coahuila, Venustiano Carranza, along with old revolutionaries demobilized by Madero, such as Pancho Villa. The northern revolutionaries fought under the name of the Constitutionalist Army, with Carranza as the "First Chief" (primer jefe). In the south, Emiliano Zapata continued his rebellion in Morelos under the Plan of Ayala, calling for the expropriation of land and redistribution to peasants. Huerta offered peace to Zapata, who rejected it.[69]

Huerta convinced Pascual Orozco, whom he fought while serving the Madero government, to join Huerta's forces.[70] Supporting the Huerta regime were business interests in Mexico, both foreign and domestic; landed elites; the Roman Catholic Church; and the German and British governments. The Federal Army became an arm of the Huerta regime, swelling to 200,000 men, many pressed into service and most ill-trained.

The US did not recognize the Huerta government. Still, from February to August 1913, it imposed an arms embargo on exports to Mexico, exempting the Huerta government and favoring the regime against emerging revolutionary forces.[71] However, President Woodrow Wilson sent a special envoy to Mexico to assess the situation, and reports on the many rebellions in Mexico convinced Wilson that Huerta was unable to maintain order. Arms ceased to flow to Huerta's government,[72] which benefited the revolutionary cause.

The US Navy made an incursion on the Gulf Coast, occupying Veracruz in April 1914. Although Mexico was engaged in a civil war at the time, the US intervention united Mexican forces in their opposition to the US. Foreign powers helped broker US withdrawal in the Niagara Falls peace conference. The US timed its pullout to support the Constitutionalist faction under Carranza.[73]

Initially, the forces in northern Mexico were united under the Constitutionalist banner, with able revolutionary generals serving the civilian First Chief Carranza in the Plan of Guadalupe. Pancho Villa began to split from supporting Carranza as Huerta was on his way out, primarily because Carranza was politically too conservative for Villa. Carranza, a rich hacienda owner whose interests were threatened by Villa's more radical ideas, opposed land reform.[74] Zapata in the south was also hostile to Carranza due to his stance on land reform.

In July 1914, Huerta resigned under pressure and went into exile. His resignation marked the end of an era since the Federal Army, a repeatedly ineffective fighting force against the revolutionaries, ceased to exist.[75]

With the exit of Huerta, the revolutionary factions decided to meet and make "a last-ditch effort to avert more intense warfare than that which unseated Huerta."[76] Called to meet in Mexico City in October 1914, revolutionaries opposed to Carranza's influence successfully moved the venue to Aguascalientes. The Convention of Aguascalientes did not reconcile the various victorious factions in the Mexican Revolution but was a brief pause in revolutionary violence. The break between Carranza and Villa became definitive during the convention. Rather than First Chief Carranza being named president of Mexico, General Eulalio Gutiérrez was chosen. Carranza and Obregón left Aguascalientes with far smaller forces than Villa's. The convention declared Carranza in rebellion against it, and civil war resumed, this time between revolutionary armies that had fought for a united cause to oust Huerta.

Villa went into alliance with Zapata to form the Army of the convention. Their forces separately moved on to the capital and captured Mexico City in 1914, which Carranza's forces had abandoned. The famous picture of Villa, sitting in the presidential chair in the National Palace, and Zapata is a classic image of the Revolution. Villa reportedly told Zapata that "the presidential chair is too big for us."[77] The alliance between Villa and Zapata did not function in practice beyond this initial victory against the Constitutionalists. Zapata returned to his southern stronghold in Morelos, where he engaged in guerrilla warfare under the Plan of Ayala.[78]

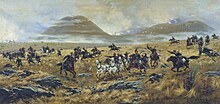

The two rival armies of Villa and Obregón met on April 6–15, 1915, in the Battle of Celaya. The shrewd, modern military tactics of Obregón met the frontal cavalry charges of Villa's forces. The Constitutionalist victory resulted in Carranza emerging as the political leader of Mexico. Villa retreated north, seemingly into political oblivion. Carranza and the Constitutionalists consolidated their position, with only Zapata opposing them until his assassination in 1919.

Constitutionalists in power, 1915–1920[edit]

Venustiano Carranza promulgated a new constitution on February 5, 1917. The Mexican Constitution of 1917, with significant amendments in the 1990s, still governs Mexico. On 19 January 1917, a secret message (the Zimmermann Telegram) was sent from the German foreign minister to Mexico proposing joint military action against the United States if war broke out. The offer included material aid to Mexico to reclaim the territory lost during the Mexican–American War. Zimmermann's message was intercepted and published, causing outrage in the US and catalyzing an American declaration of war against Germany in early April. Carranza then formally rejected the offer, and the threat of war with the US eased.[79]

Carranza was assassinated in 1920 during an internal feud among his former supporters over who would replace him as president.

Consolidation of revolution, 1920–1940[edit]

Northern revolutionary generals as presidents[edit]

Three Sonoran generals of the Constitutionalist Army, Álvaro Obregón, Plutarco Elías Calles, and Adolfo de la Huerta dominated Mexican politics in the 1920s. Their life experience in Mexico's northwest, described as a "savage pragmatism"[80] was in a sparsely settled region, conflict with Natives, secular rather than religious culture, and independent, commercially oriented ranchers and farmers. This differed from the subsistence agriculture of the dense population of central Mexico's strongly Catholic indigenous and mestizo peasantry. Obregón was the dominant triumvirate member, the leading general in the Constitutionalist Army, who had defeated Pancho Villa in battle. All three were also skilled politicians and administrators. In Sonora, they "formed their professional army, patronized and allied themselves with labor unions, and expanded the government authority to promote economic development." Once in power, they scaled this up to the national level.[81]

Obregón presidency, 1920–1924[edit]

Obregón, Calles, and de la Huerta revolted against Carranza in the Plan of Agua Prieta in 1920. Following the interim presidency of Adolfo de la Huerta, elections were held, and Obregón was elected for a four-year presidential term. His government accommodated many elements of Mexican society except the most conservative clergy and wealthy landowners. He was a revolutionary nationalist, holding seemingly contradictory views as a socialist, a capitalist, a Jacobin, a spiritualist, and an Americanophile.[82]

He was able to implement policies emerging from the revolutionary struggle successfully; in particular, the successful policies were the integration of urban, organized labor into political life via CROM, the improvement of education and Mexican cultural production under José Vasconcelos, the movement of land reform, and the steps taken toward instituting women's civil rights. His main tasks in the presidency were consolidating state power in the central government and curbing regional strongmen (caudillos), obtaining diplomatic recognition from the United States, and managing the presidential succession in 1924 when his term ended.[83] His administration began constructing what one scholar called "an enlightened despotism, a ruling conviction that the state knew what ought to be done and needed plenary powers to fulfill its mission."[84] After the nearly decade-long violence of the Mexican Revolution, reconstruction in the hands of a strong central government offered stability and a path of renewed modernization.

Obregón knew his regime needed to secure recognition in the United States. With the promulgation of the Mexican Constitution of 1917, the Mexican government was empowered to expropriate natural resources. The U.S. had considerable business interests in Mexico, especially oil, and the threat of Mexican economic nationalism to big oil companies meant that diplomatic recognition could hinge on Mexican compromise in implementing the constitution. 1923, when the Mexican presidential elections were on the horizon, the two governments signed the Bucareli Treaty. The treaty resolved questions about foreign oil interests in Mexico, largely favoring U.S. interests, but Obregón's government gained U.S. diplomatic recognition. With that, arms and ammunition began flowing to revolutionary armies loyal to Obregón.[85]

Since Obregón had named his fellow Sonoran general, Plutarco Elías Calles, as his successor, Obregón was imposing a "little known nationally and unpopular with many generals,"[85] thereby foreclosing the ambitions of fellow revolutionaries, particularly his old comrade Adolfo de la Huerta. De la Huerta staged a serious rebellion against Obregón. But Obregón once again demonstrated his brilliance as a military tactician who now had arms and even air support from the United States to suppress it brutally. Fifty-four former Obregonistas were shot in the event.[86] Vasconcelos resigned from Obregón's cabinet as minister of education.

Although the Constitution of 1917 had stronger anticlerical articles than the previous constitution, Obregón largely sidestepped confrontation with the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico. Since political opposition parties were essentially banned, the Catholic Church "filled the political void and played the part of a substitute opposition."[87]

Calles presidency, 1924–1928[edit]

The 1924 presidential election was not a demonstration of free and fair elections, but the incumbent Obregón could not stand for re-election, thereby acknowledging that revolutionary principle. He completed his presidential term still alive, the first since Porfirio Díaz. Candidate Plutarco Elías Calles embarked on one of the first populist presidential campaigns in the nation's history, calling for land reform and promising equal justice, more education, additional labor rights, and democratic governance.[88] Calles tried to fulfill his promises during his populist phase (1924–26) and a repressive anti-clerical phase (1926–28). Obregón's stance toward the church appears pragmatic since he had many other issues to deal with. Still, his successor, Calles, a vehement anticlerical, took on the church as an institution when he succeeded to the presidency, bringing about violent, bloody, and protracted conflict known as the Cristero War.

Cristero War (1926–1929)[edit]

The Cristero War of 1926 to 1929 was a counter-revolution against the Calles regime set off by his persecution of the Catholic Church in Mexico[89] and specifically the strict enforcement of the anti-clerical provisions of the Mexican Constitution of 1917 and the expansion of further anti-clerical laws. The formal rebellions began early in 1927,[90] with the rebels calling themselves Cristeros because they felt they were fighting for Jesus Christ himself. The laity stepped into the vacuum created by the removal of priests. In the long run, the Church was strengthened.[91] The Cristero War was resolved diplomatically, largely with the help of the U.S. Ambassador, Dwight Morrow.[92]

The conflict claimed about 250,000 lives, including civilians and Cristeros killed during raids after the war's end.[93] As promised in the diplomatic resolution, the anti-clerical laws remained on the books, but the federal government made no organized attempt to enforce them. Nonetheless, persecution of Catholic priests continued in several localities, fueled by local officials' interpretation of the resolutions.[citation needed]

Maximato and the Formation of the Ruling Party[edit]

After Calles' presidential term ended in 1928, former president Alvaro Obregón won the presidency, but he was assassinated immediately after the July election, leaving a power vacuum. Revolutionary generals and others in the power elite agreed that Congress should appoint an interim president, and new elections were held in 1928. In his final address to Congress on 1 September 1928, President Calles declared the end of strongman rule, a ban on Mexican presidents serving again in that office, and that Mexico was now entering an age of rule by institutions and laws.[94] Congress chose Emilio Portes Gil to serve as interim president. Calles became the power behind the presidency in this period, known as the Maximato.

Calles created a more permanent solution to presidential succession by founding the National Revolutionary Party (PNR) in 1929. The party brought together regional caudillos and integrated labor organizations and peasant leagues in a party that could better manage the political process. For the six-year term that Obregón was to serve, three presidents held office: Emilio Portes Gil, Pascual Ortiz Rubio, and Abelardo L. Rodríguez. In 1934, the PNR chose Calles-supporter Lázaro Cárdenas, a revolutionary general with a political power base in Michoacan, as the candidate of the PNR for the Mexican presidency. After an initial period of acquiescence to Calles's role in intervening in the presidency, Cárdenas out-maneuvered his former patron and eventually sent him into exile. Cárdenas reformed the PNR structure, creating the PRM (Partido Revolucionario Mexicano), the Mexican Revolutionary Party, which included the army as a party sector. He had convinced most of the remaining revolutionary generals to hand over their armies to the Mexican Army; some thus consider the date of the PRM party's foundation to be the end of the Revolution. The party was re-structured again in 1946 and renamed the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and held power continuously until 2000. After establishing itself as the ruling party, the PRI monopolized all the political branches: it did not lose a senate seat until 1988 or a gubernatorial race until 1989.[95]

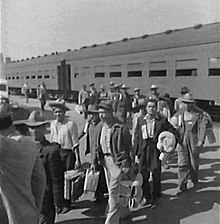

Revitalization of the revolution under Cárdenas[edit]