Italian irredentism in Nice

Italian irredentism in Nice was the political movement supporting the annexation of the County of Nice to the Kingdom of Italy.

According to some Italian nationalists and fascists like Ermanno Amicucci, Italian- and Ligurian-speaking populations of the County of Nice (Italian: Nizza) formed the majority of the county's population until the mid-19th century.[1] However, French nationalists and linguists argue that both Occitan and Ligurian languages were spoken in the County of Nice.

During the Italian unification, in 1860, the House of Savoy allowed the Second French Empire to annex Nice from the Kingdom of Sardinia in exchange for French support of its quest to unify Italy. Consequently, the Niçois were excluded from the Italian unification movement and the region has since become primarily French-speaking.

History[edit]

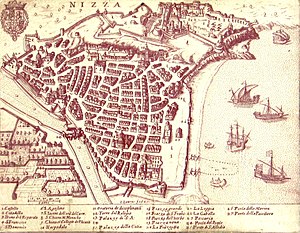

The region around Nicaea, as Nice was then known in Latin, was inhabited by the Ligures until its subsequent occupation by the Roman Empire after their subjugation by Augustus. According to Theodor Mommsen, fully Romanized by the 4th century AD, when the invasions of the Migration Period began.

The Franks conquered the region after the fall of Rome, and the local Romance language speaking populations became integrated within the County of Provence (with a brief period of independence as a maritime republic (1108–1176).) In 1388, the commune of Nice sought the protection of the Duchy of Savoy, and Nice continued to be controlled, directly or indirectly, by the Savoy monarchs until 1860.

During this time, the maritime strength of Nice rapidly increased until it was able to cope with the Barbary pirates. Fortifications were largely extended by the House of Savoy and the roads of the city and surrounding region improved. Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy, abolished the use of Latin and established Italian as the official language of Nice in 1561.[2]

Conquered in 1792 by the armies of the French First Republic, the County of Nice was part of France until 1814, after which it was placed under the protection of the Kingdom of Sardinia by the Congress of Vienna.

After the Treaty of Turin was signed in 1860 between the Sardinian king and Napoleon III as a consequence of the Plombières Agreement, the county was again and definitively ceded to France as a territorial reward for French assistance in the Second Italian War of Independence against Austria, which saw Lombardy united with Piedmont-Sardinia. King Victor-Emmanuel II, on April 1, 1860, solemnly asked the population to accept the change of sovereignty, in the name of Italian unity, and the cession was ratified by a regional referendum. Italophile manifestations and the acclamation of an “Italian Nice” by the crowd are reported on this occasion.[3] These manifestations cannot influence the course of events. A plebiscite was voted on April 15 and April 16, 1860. The opponents of annexation called for abstention, hence the very high abstention rate. The “yes” vote won 83% of registered voters throughout the county of Nice and 86% in Nice, partly thanks to pressure from the authorities.[4] This is the result of a masterful operation of information control by the French and Piedmontese governments, in order to influence the outcome of the vote in relation to the decisions already taken.[5] The irregularities in the plebiscite voting operations were evident. The case of Levens is emblematic: the same official sources recorded, faced with only 407 voters, 481 votes cast, naturally almost all in favor of joining France.[6]

The Italian language was the official language of the County, used by the Church, at the town hall, taught in schools, used in theaters and at the Opera, was immediately abolished and replaced by French.[7][8] Discontent over annexation to France led to the emigration of a large part of the Italophile population, also accelerated by Italian unification after 1861. A quarter of the population of Nice, around 11,000 people from Nice, decided to voluntarily exile to Italy.[9][10] The emigration of a quarter of the Niçard Italians to Italy took the name of Niçard exodus.[11] Many Italians from Nizza then moved to the Ligurian towns of Ventimiglia, Bordighera and Ospedaletti,[12] giving rise to a local branch of the movement of the Italian irredentists which considered the re-acquisition of Nice to be one of their nationalist goals.

Giuseppe Garibaldi, born in Nice, tenaciously opposed the cession of his hometown to France, arguing that the Plebiscite he ratified in the treaty was vitiated by electoral fraud. In 1871, during the first free elections in the County, the pro-Italian lists obtained almost all the votes in the legislative elections (26,534 votes out of 29,428 votes cast), and Garibaldi was elected deputy at the National Assembly. Pro-Italians take to the streets cheering “Viva Nizza! Viva Garibaldi!”. The French government sends 10,000 soldiers to Nice, closes the Italian newspaper Il Diritto di Nizza and imprisons several demonstrators. The population of Nice rose up from February 8 to 10 and the three days of demonstration took the name of "Niçard Vespers". The revolt is suppressed by French troops. On February 13, Garibaldi was not allowed to speak at the French parliament meeting in Bordeaux to ask for the reunification of Nice to the newborn Italian unitary state, and he resigned from his post as deputy.[13] The failure of Vespers led to the expulsion of the last pro-Italian intellectuals from Nice, such as Luciano Mereu or Giuseppe Bres, who were expelled or deported.

The pro-Italian irredentist movement persisted throughout the period 1860-1914, despite the repression carried out since the annexation. The French government implemented a policy of Francization of society, language and culture.[14] The toponyms of the communes of the ancient County have been francized, with the obligation to use French in Nice,[15] as well as certain surnames (for example the Italian surname "Bianchi" was francized into "Leblanc", and the Italian surname "Del Ponte" was francized into "Dupont").[16] This led to the beginning of the disappearance of the Niçard Italians. Many intellectuals from Nice took refuge in Italy, such as Giovan Battista Bottero who took over the direction of the newspaper La Gazzetta del Popolo in Turin. In 1874, it was the second Italian newspaper by circulation, after Il Secolo in Milan.

Italian-language newspapers in Nice were banned. In 1861, La Voce di Nizza was closed (temporarily reopened during the Niçard Vespers), followed by Il Diritto di Nizza, closed in 1871.[13] In 1895 it was the turn of Il Pensiero di Nizza, accused of irredentism. Many journalists and writers from Nice wrote in these newspapers in Italian. Among these are Enrico Sappia, Giuseppe André, Giuseppe Bres, Eugenio Cais di Pierlas and others.

Another Niçard Italian, Garibaldian Luciano Mereu, was exiled from Nice in November 1870, together with the Garibaldians Adriano Gilli, Carlo Perino and Alberto Cougnet.[17] In 1871, Luciano Mereu was elected City Councilor in Nice during the term of Mayor of Augusto Raynaud (1871–1876) and was a member of the Garibaldi Commission of Nice, whose president was Donato Rasteu. Rasteu remained in office until 1885.[18]

This led to the beginning of the disappearance of the Niçard Italians. Many intellectuals from Nice took refuge in Italy, such as Giovan Battista Bottero who took over the direction of the newspaper La Gazzetta del Popolo in Turin. In 1874, it was the second Italian newspaper by circulation, after Il Secolo in Milan.

Giuseppe Bres tried to counter the French claim that the Niçard dialect was Occitan and not Italian, publishing his Considerations on Niçard dialect in 1906 in Italy.[19]

Benito Mussolini considered the annexation of Nice to be one of his main targets. In 1940, the County of Nice was occupied by the Italian army and the newspaper Il Nizzardo ("The Niçard") was restored there. It was directed by Ezio Garibaldi, grandson of Giuseppe Garibaldi. Only Menton was administered until 1943 as if it were an Italian territory, even if the Italian supporters of Italian irredentism in Nice wanted to create an Italian governorate (on the model of the Governorate of Dalmatia) up to the Var river or at least a "Province of the Western Alps".[20]

The Italian occupation government was far less severe than that of Vichy France; thus, thousands of Jews took refuge there. For a while, the city became an important mobilization center for various Jewish organizations. However, when the Italians signed the Armistice of Cassibile with the Allies, German troops invaded the region on September 8, 1943, and initiated brutal raids. Alois Brunner, the SS official for Jewish affairs, was placed at the head of units formed to search out Jews. Within five months, 5,000 Jews were caught and deported.[21]

The area was returned to France following the war and in 1947, the areas of La Brigue and Tende, which had remained Italian after 1860 were ceded to France. Thereafter, a quarter of the Niçard Italians living in that mountainous area moved to Piedmont and Liguria in Italy (mainly from the Roya Valley and Tenda).[22]

Today, after a sustained process of Francization conducted since 1861, the former county is predominantly French-speaking. Only along the coast around Menton and in the mountains around Tende there are still some native speakers of the original Intemelio dialect of Ligurian.[23]

Currently the area is part of the Alpes-Maritimes department of France.

Language[edit]

In Nice, the language of the Church, municipality, law, school, and theater was always the Italian language....From 460 AD to the mid-19th century, the County of Nice counted 269 writers, not including those still living. Of these 269 writers, 90 used Italian, 69 Latin, 45 Italian and Latin, 7 Italian and French, 6 Italian with Latin and French, 2 Italian with Nizzardo dialect and French, 2 Italian and Provençal.[24]

Before the year 1000, the area of Nice was part of the Ligurian League, under the Republic of Genoa; thus, the population spoke a dialect different from the one typical of western Liguria: that spoken in the eastern part of Liguria, which today is called "Intemelio"[25] was spoken. The medieval writer and poet Dante Alighieri wrote in his Divine Comedy that the Var near Nice was the western limit of the Italian Liguria.

Around the 12th century, Nice came under the control of the French Capetian House of Anjou, who favored the immigration of peasants from Provence that brought with them their Occitan language.[26] From 1388 to 1860, the County of Nice came under Savoyard rule and remained connected to the Italian dialects and peninsula. In the fantastic linguistics and historical inventions of the Italian fascists, in this era, the people of the mountainous areas of the upper Var Valley started to lose their former Ligurian linguistic characteristics and began to adopt Provençal influences. They believe that in those centuries the local Niçard dialect became distinct from the Monégasque of the Principality of Monaco.

Traditionally, Italian linguists maintained that Niçard originated as a Ligurian dialect.[27] Before the annexation of the county of Nice to France in 1860, all the historical texts and archives of the city were written either in the Ligurian language, or in Italian.[28] On the other hand, French linguists argue that Niçard is a dialect of Occitan[29] while conceding that Monégasque is a dialect of Ligurian. However, Sue Wright notes that before the Kingdom of Sardinia ceded the County of Nice to France, "Nice was not French-speaking before the annexation but underwent a shift to French in a short time... and it is surprising that the local Italian dialect, the Nissart, disappeared quickly from the private domain."[30] She also wrote that one of the main reasons of the disappearance of the Italian language in the County was because "(m)any of the administrative class under Piedmont-Savoy ruler, the soldiers; jurists; civil servants and professionals, who used Italian in their working lives, moved [back] to Piedmont, after the annexation and their places and roles were taken by newcomers from France".

Indeed, immediately after 1861, the French government closed all the Italian language newspapers, and more than 11,000 Niçard Italians moved to the Kingdom of Italy. The sheer scale of the Niçard exodus can be inferred from the fact that in the Savoy census of 1858, Nice had only 44,000 inhabitants. In 1881, The New York Times wrote, "Before the French annexation, the Niçois were quite as much Italian as the Genoese and their dialect was if anything, nearer the Tuscan, than is the harsh dialect of Genoa.[31]

Giuseppe Garibaldi defined his "Nizzardo" as an Italian dialect, albeit with strong similarities to Occitan and with some French influences, and for this reason promoted the union of Nice to the Kingdom of Italy.

Today some scholars, like the German Werner Forner, the French Jean-Philippe Dalbera and the Italian Giulia Petracco Sicardi, agree that the Niçard has some characteristics - phonetic, lexical and morphological - that are typical of western Ligurian. The French scholar Bernard Cerquiglini pinpoints in his Les langues de France the actual existence of a Ligurian minority in Tende, Roquebrune-Cap-Martin and Menton.

Another reduction in the number of the Nizzardi Italians happened after World War II, when defeated Italy was forced to surrender to France the small mountainous area of the County of Nice, that had been retained in 1860. From the Val di Roia, Tenda and Briga, one quarter of the local population moved to Italy in 1947. The entire population of Nice before the 1960s had Italian surnames.[32] The Niçard Vespers were three days of popular uprising of the inhabitants of Nice in 1871, promoted by Giuseppe Garibaldi in favor of the union of the county of Nice with the Kingdom of Italy.[33]

In the century of nationalism between 1850 and 1950, the Nizzardi Italians were reduced from a majority of 70%[34] of the 125,000 people living in the County of Nice at the time of the French annexation, to a current minority of nearly two thousand (in the area of Tende and Menton) today.

Nowadays, even though the populations of Nice and its surroundings are fluent in French, some still speak the original Niçard language of Nissa La Bella.

See also[edit]

- Italian irredentism

- Giuseppe Garibaldi

- Monégasque dialect

- Mentonasc dialect

- Italian irredentism in Corsica

References[edit]

- ^ Amicucci, Ermanno. Nizza e l’Italia. p 64

- ^ Jörg Mettler, Hans & Éthier, Benoit Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur (1998) p. 24

- ^ Ruggiero, Alain (2006). Nouvelle Histoire de Nice (in French).

- ^ Ruggiero, Alain, ed. (2006). Nouvelle histoire de Nice. Toulouse: Privat. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-2-7089-8335-9.

- ^ Kendall Adams, Charles (1873). "Universal Suffrage under Napoleon III". The North American Review. 0117: 360–370.

- ^ Dotto De' Dauli, Carlo (1873). Nizza, o Il confine d'Italia ad Occidente (in Italian).

- ^ Large, Didier (1996). "La situation linguistique dans le comté de Nice avant le rattachement à la France". Recherches régionales Côte d'Azur et contrées limitrophes.

- ^ Paul Gubbins and Mike Holt (2002). Beyond Boundaries: Language and Identity in Contemporary Europe. pp. 91–100.

- ^ Peirone, Fulvio (2011). Per Torino da Nizza e Savoia. Le opzioni del 1860 per la cittadinanza torinese, da un fondo dell'archivio storico della città di Torino (in Italian). Turin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ ""Un nizzardo su quattro prese la via dell'esilio" in seguito all'unità d'Italia, dice lo scrittore Casalino Pierluigi" (in Italian). August 28, 2017. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ ""Un nizzardo su quattro prese la via dell'esilio" in seguito all'unità d'Italia, dice lo scrittore Casalino Pierluigi" (in Italian). August 28, 2017. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ "Nizza e il suo futuro" (in Italian). Liberà Nissa. Archived from the original on February 3, 2019. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

- ^ a b Courrière, Henri (2007). "Les troubles de février 1871 à Nice". Cahiers de la Méditerranée (74): 179–208. doi:10.4000/cdlm.2693.

- ^ Paul Gubbins and Mine Holt (2002). Beyond Boundaries: Language and Identity in Contemporary Europe. pp. 91–100.

- ^ "Il Nizzardo" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ "Un'Italia sconfinata" (in Italian). February 20, 2009. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ Letter from Alberto Cougnet to Giuseppe Garibaldi, Genoa, December 7, 1867 - "Garibaldi Archive", Milan - C 2582

- ^ "Lingua italiana a Nizza" (in Italian). Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ "Considerazioni Sul Dialetto Nizzardo" (in Italian). Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ Davide Rodogno. Il nuovo ordine mediterraneo - Le politiche di occupazione dell'Italia fascista in Europa (1940 - 1943) p.120-122 (In italian)

- ^ Paldiel, Mordecai (2000). Saving the Jews: Amazing Stories of Men and Women who Defied the "final Solution". Schreiber. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-887563-55-0.

- ^ Intemelion

- ^ Intemelion 2007

- ^ Francesco Barberis: "Nizza Italiana" p.51

- ^ Werner Forner.À propos du ligurien intémélien - La côte, l'arrière-pays, Travaux du Cercle linguistique de Nice, 7-8, 1986, pp. 29-62.

- ^ Gray, Ezio. Le terre nostre ritornano... Malta, Corsica, Nizza. Chapter 2

- ^ Zuccagni-Orlandini, Attilio. Raccolta di dialetti italiani con illustrazioni etnologiche 1864

- ^ Alpes-Maritimes, Département des. "Outils de recherche et archives numérisées". Département des Alpes-Maritimes (in French). Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ^ Bec, Pierre. La Langue Occitane. p. 58

- ^ Gubbins, Paul; Holt, Mike (2002). Beyond Boundaries: Language and Identity in Contemporary Europe. Multilingual Matters. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-85359-555-4.

- ^ https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1881/03/29/98551254.pdf New York Times, 1881

- ^ Alpes-Maritimes, Département des. "Outils de recherche et archives numérisées". Département des Alpes-Maritimes (in French). Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ^ André, Giuseppe (1875). Nizza, negli ultimi quattro anni (in Italian). A. Gilletta.

- ^ Amicucci, Ermanno. Nizza e l’Italia. p. 126

Bibliography[edit]

- André, Giuseppe. Nizza, negli ultimi quattro anni. Editore Gilletta. Nizza, 1875

- Amicucci, Ermanno. Nizza e l’Italia. Ed. Mondadori. Milano, 1939.

- Barelli Hervé, Rocca Roger. Histoire de l'identité niçoise. Serre. Nice, 1995. ISBN 2-86410-223-4

- Barberis, Francesco. Nizza italiana: raccolta di varie poesie italiane e nizzarde, corredate di note. Editore Tip. Sborgi e Guarnieri (Nizza, 1871). University of California, 2007

- Bec, Pierre. La Langue Occitane. Presses Universitaires de France. Paris, 1963

- Gray, Ezio. Le terre nostre ritornano... Malta, Corsica, Nizza. De Agostini Editoriale. Novara, 1943

- Holt, Edgar. The Making of Italy 1815–1870, Atheneum. New York, 1971

- Ralph Schor, Henri Courrière (dir.), Le comté de Nice, la France et l'Italie. Regards sur le rattachement de 1860. Actes du colloque organisé à l'université de Nice Sophia-Antipolis, 23 avril 2010, Nice, éditions Serre, 2011, 175 p.

- Stuart, J. Woolf. Il risorgimento italiano. Einaudi. Torino, 1981

- Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis, Centre Histoire du droit. Les Alpes Maritimes et la frontière 1860 à nos jours. Actes du colloque de Nice (1990). Ed. Serre. Nice,1992

- Werner Forner. L’intemelia linguistica, ([1] Intemelion I). Genoa, 1995.

External links[edit]

- (in Italian) Nice and Italian Irredentism

- (in French) Map of the Languages of France, with reference to the Niçard and Genoese

- (in Italian) Magazine about Briga and Tenda

- (in Italian) Fancesco Barberis: "Nizza Italiana" (Google Books)