Josef Hoffmann

Josef Franz Maria Hoffmann | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 15 December 1870 |

| Died | 7 May 1956 (aged 85) Vienna, Austria |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Children | Wolfgang Hoffmann |

| Buildings | Sanatorium Purkersdorf Stoclet Palace Ast Residence Skywa-Primavesi Residence |

| Projects | Wiener Werkstätte |

Josef Hoffmann (15 December 1870 – 7 May 1956) was an Austrian-Moravian architect and designer. He was among the founders of Vienna Secession and co-establisher of the Wiener Werkstätte. His most famous architectural work is the Stoclet Palace, in Brussels, (1905–1911) a pioneering work of Modern Architecture, Art Deco and peak of Vienna Secession architecture.

Biography[edit]

Early life and education[edit]

Hoffmann was born in Brtnice / Pirnitz, Moravia (now part of the Czech Republic), Austria-Hungary.[1] His father was modestly wealthy, the co-owner of a textile factory, and mayor of the small town. His father encouraged him to become a lawyer or a civil servant, and sent him to a prestigious upper school, but he was very unhappy there. He later described his school years as "a shame and a torture which poisoned my youth and left me with a feeling of inferiority which has lasted until this day." [2]

In 1887, he transferred instead to the Higher School of Arts and Crafts State in Brno / Brünn beginning in 1887 where he received his baccalaureate in 1891. In 1892, he began his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna under Karl Freiherr von Hasenauer and Otto Wagner, two of the most prestigious architects of the period. There he also met another rising architect of the time, Joseph Maria Olbrich. In 1895, Hoffman, together with Olbrich, Koloman Moser and Carl Otto Czeschka and several others, founded a group called the Siebener Club, a forerunner of the future Vienna Secession. Under Wagner's guidance, Hoffman's graduation project, an updated Renaissance building, won the Prix de Rome and allowed Hoffmann to travel and study for a year in Italy. [2]

The Vienna Secession (1897–1905)[edit]

Upon his return from Italy in 1897, he joined Wagner's architectural firm, and in the same year he joined the new movement launched by Wagner, Gustav Klimt, and others; the Society of Austrian Fine Artists, better known as the Vienna Secession.[3] He immediately went to work on the design of the Secession Building, the first gallery of the movement, designing the foyer and the office, and planning the first exhibitions in the building.[2]

He wrote his first manifesto for the Secession at this time, calling for buildings which were stripped of useless ornament. "It is not a matter of overlaying a framework with ridiculous ornament in molded cement, made industrially, nor imposing as a model Swiss architecture or houses with gables. It is a matter of creating a harmonious ensemble, of great simplicity, adapted to the individual... and which presents natural colors and a form made by the hand of an artist..." [2] In his writing, Hoffmann did not entirely reject historicism; he praised the model of the British Arts and Crafts Movement, and urged artists to renew local forms and traditions. He wrote that the basic elements of the new style were authenticity in the use of materials, unity of decor, and the choice of a style adapted to the site.[4]

In 1899, at the age of twenty-nine, he began to teach at the Kunstgewerbeschule, now University of Applied Arts Vienna. He designed the Vienna arts exhibition for the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition, which exposed the Secession style to an international audience. In 1899, he also designed the Eighth Exposition of the Secession, one of the most important exhibitions at the time, due to its international participants. In addition to works by Secession artists, it featured works by the French artist Jules Meier-Graefe, the Belgian Henry van de Velde, Charles Ashbee, and especially the works by the Scottish designers Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh from Glasgow. This exhibit included a group of model houses in the Hohe Warte neighborhood of Vienna which displayed features of Arts-and-Crafts movement, including windows divided in small squares, and the gable roof. [5]

During this period, Hoffmann's work became more rigorous, more geometric, and less ornamental. He favored the use of geometric forms, especially squares, and black and white surfaces, explaining later that "these forms, intelligible to everyone, had never appeared in previous styles". [6] He was in charge of designing the frequent exhibits held in the Secession gallerias, including the setting for Gustav Klimt's celebrated frieze devoted to Beethoven. [6]

-

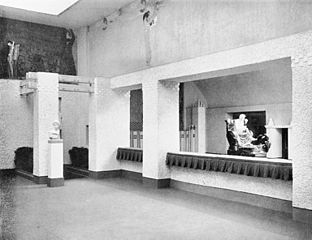

Installation by Josef Hoffmann of the Beethoven Frieze by Gustav Klimt in the Secession Building (1902)

-

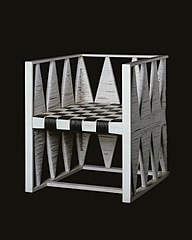

Cabinet for photographs (circa 1902)

The Wiener Werkstätte (1903–1932)[edit]

Hoffmann was married in 1898 to Anna Hladik, and they had a son, Wolfgang, born in 1900. He was extremely occupied with the Paris Exposition of 1900, and the other exhibitions in Vienna. During this period, he built only a small number of buildings, including the transformation of a house for his friend Paul Wittgenstein. He also built several town or country houses for his colleagues and friends, as well as a Lutheran church and a house for the pastor in St. Aegyd am Neuwald, in lower Austria.[7]

In 1903, along with Koloman Moser, and banker Fritz Wärndorfer, who provided most of the capital, he launched a much more ambitious venture, the Wiener Werkstätte, an enterprise of artists and craftsmen working together to create all the elements of a complete work of art, or Gesamtkunstwerk.[8] including architecture, furniture, lamps, glass and metal work, dishes and textiles.

Hoffmann designed a wide variety of objects for the Wiener Werkstätte. Some of them, like the Sitzmaschine Chair, a lamp, and sets of glasses are on display in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.[9] and a tea service in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[10] Many of the works were hand-made by the artisans of the group and some by industrial manufacturers.

Some of Hoffmann's domestic designs can still be found in production today, such as the Rundes Modell cutlery set that is manufactured by Alessi.[11] Originally produced in silver, the range is now produced in high quality stainless steel. Another example of Hoffmann's strict geometrical lines and the quadratic theme is the iconic Kubus Armchair. Designed in 1910, it was presented at the International Exhibition held in Buenos Aires on the centennial of Argentinean Independence known as May Revolution. Hoffmann's constant use of squares and cubes earned him the nickname Quadratl-Hoffmann ("Square Hoffmann"). Hoffmann's style gradually became more sober and abstract and his work was limited increasingly to functional structures and domestic products.

The workshop concept flourished in its early years and spread. In 1907, Hoffmann was co-founder of the Deutscher Werkbund, and in 1912 of the Österreichischer Werkbund (or Austrian Werkbund). But the workshop ran up against the First World War and then the Great Depression, which hit Germany and Austria especially hard. It was forced to close in 1932. [12]

-

Armchair of wood and cane (1903), Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City)

-

Chair for the Purkersdorf Sanatorium (1904–05)

-

Sitzmaschine Armchair (1905)

-

Kubus armchair (1910)

-

Designs by Hoffmann (1904–08)

The Purkersdorf Sanatorium (1904–05)[edit]

In 1905, [13] Hoffmann finished his first great work in the town of Purkersdorf near Vienna, the Sanatorium Purkersdorf. It was a distinct move away from the Arts and Crafts style, as a major precedent and inspiration for the modern architecture that would develop in the first half of the 20th century,[14] It had the clarity, simplicity, and logic that foreshadowed Neue Sachlichkeit.[15]

-

General view

-

Entrance Hall

-

Gallery

-

Meeting room

The Stoclet Palace (1905–1911)[edit]

The Stoclet Palace in Brussels, made in collaboration with Gustav Klimt, is the most famous work of Hoffmann, the Vienna Secession, and of the Wiener Werkstätte. It is a visible turning point from historical styles to modern architecture.[16] It was built for Adolphe Stoclet, the heir of a wealthy Belgian banking family, who had lived in Milan and Vienna, and was familiar with the Vienna Secession. Hoffmann presented the plans in 1905, but the construction, in three stages, was not completed until 1911. [17]

The exterior is extraordinarily modern, in strict geometric forms, with touches of decoration. It is covered in white Norwegian marble, while the edges of the forms and the windows are bordered with sculpted metal. The central tower, nearly twenty meters high, is made of assembled cubic forms and crowned with four copper statues with statuary. The plan has two axes, perpendicular to each other. The railings around the building and on the tower have had stylized ornamental designs, and even the plants in the garden are sculpted into geometric forms to complement the architecture.

The interior, by Hoffmann and the artists of the Wiener Werkstätte, is like a series of stage sets, offering carefully planned views from one room to the other, and decorated with colorful mosaics made by Klimt, as well as walls of white marble and antique green marble. The floors are made of parquet from exotic woods, with different designs in each room. The dining room features a set of two mosaic murals by Klimt, in a setting of marble columns and mosaics by Klimt, along with geometric marble columns and walls covered with stylized floral patterns designed by Hoffmann and Klimt. Every detail of the house, including the rectangular while marble bathtub, surrounded by marble plaques with sculpture and placed on a blue marble floor, the polished pallisander wood paneling in the bedroom, and the kitchen counters, floor and furniture, were made by the Werkstätte and planned to harmonize with the overall design. The building is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. [17]

-

Stoclet Palace (1905–1911)

-

Windows of the Stoclet Palace

-

Detail of the facade, made of reinforced concrete covered with marble plaques

-

Photograph of the Stoclet Palace's dining room, with furniture by Hoffmann and ceramic frieze by Gustav Klimt

Villas and interiors (1906–1914)[edit]

In the years during and after he designed the Stoclet Palace, Hoffmann continued to build interesting structures, but none gained the attention of the earlier work. notable works made by Hoffmann included a hunting lodge designed for Karl Wittgenstein (1906), the father of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein was an important patron of the arts, and provided funding for the construction of the Secession House in Vienna. The hunting lodge has a rustic exterior but an extremely modern interior; the interior walls are paneled with exotic woods in geometric patterns, with gilded decorative elements. Every element, from the dishes to the chairs and parquet floor, was carefully harmonized and proportioned. The antechamber was decorated by the Werkstätte, and features paintings by Carl Otto Czeschka, ceramics by Richard Luksch, and painting on glass attributed to Koloman Moser.

A more modest but colorful creation of Hoffmann was the interior of a popular avant-garde night club, the Fledermaus Cabaret in Vienna (1907) made with the help of the Vienna Werkstätte. The walls and counters were covered with white plaster and or multicolor tiles, while the floors had a checkerboard pattern of black and white. It was designed, following the Werkstätte doctrine, as a total work of art, from the furniture and dishes to the light fixtures, menus, tickets and posters. Hoffmann designed the Fledermaus chairs, which became a symbol of the style.[18]

Other important works include the Hochstetter House in Vienna (1906–1907), and the Villa Ast in Vienna (1909–1911) which was constructed for Edouard Ast, a businessman and building contractor who pioneered the use of reinforced concrete in Austria, and was a major funder of the Werkstätte. The house was built of reinforced concrete, encrusted with decoration and sculpture. Strongly vertical in design, it was sited atop a stone pedestal that contained the basement, and featured a modern interpretation of a classical facade. It had a loggia with windows on one side, looking out at the garden, which connected with a gallery giving access to the garden, decorated with winding water basins made of concrete. Like the Stoclet Palace, the interior was decorated with fine veined marble plaques of different colors, and with a colorful painting by Klimt. [19]

In 1911–1912, Hoffmann was engaged by Moriz Gallia, a major patron of the Werkstätte, to design the interiors of the five main rooms of his new apartment, including all furniture, rugs, and light fittings. Much of the furniture, mostly in richly carved, ebonised wood with boldly coloured upholstery, survives in the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia, as the Hoffmann Gallia apartment collection.

Another major work was the Villa Skywa-Primavesi (1913–1916), also in Vienna, for the industrialist Otto Primavesi. This was a veritable palace, 1000 square meters not counting the adjoining buildings, placed in a park and built in the neoclassical modern style, all in white, that Hoffmann favored during this period. The frontons of the building featured sculptures by Anton Hanak. The interiors were in the same modernized neoclassical style, decorated with parquet floors of rare woods, marble plaques on the walls, and sculptural decoration.

-

Decoration for the Cabaret Fledermaus (1907)

-

Chair for the Caberet Fledermaus (1906–14)

-

Villa Skywa-Primavesi (1913-1916)

Between the Wars (1918–1938)[edit]

Following the First World War, Hoffmann built his last two villas. The first was a country house for Edouard Ast at Velden am Worthersee in Carinthia. It was in a simpler geometric style, with white walls, cubic forms, and just a touch exterior decor, a classical pediment over the front door topped with statuary.

The second project was a villa for Sonya Knips, famous as the model for one of Klimt's earliest works. She had married the industrialist Anton Knips, who was a major patron of the Werkstätte. This house was different from the others, less geometric in its facade and showed the inspiration of the British Arts and Crafts Movement in its roof and dormer windows. The interior featured a perfect harmony of furniture, wall decoration and detail, and was originally complemented by three major Klimt paintings, now in museums. [20]

In the 1920s, Hoffmann became particularly interested in building public housing and apartment buildings for working-class residents, to relieve the severe housing shortage after the War. His first such project was in Klosehof, a wealthy neighborhood in Vienna. This was a square building five stories high, sixty meters by sixty meters, with a central courtyard, in which he planned a tower six stories high, with more apartments and, on the ground floor, a day care center for children. The facade was simple, covered with white plaster. The only decorative details were simple columns and pediments over the entrances, and a gabled roof, red trim around the windows.

As the economic crisis of the 1930s deepened, Hoffmann built more public housing in Vienna. The largest project was at Laxenburgerstrasse 94, built between 1928 and 1932. It contained 332 apartments, each with a small balcony, organized in a six-story buildingblock around a central courtyard. This simple, functional structure became a model for similar buildings built in Vienna and other cities after the War. [20]

Hoffmann had been a founding member of the Austrian Werkbund, founded in 1914, modeled after the celebrated German Werkbund. He organized several exhibitions for the Werkbund, experimenting with modern architecture. In 1930–32, the Austrian Werkbund created an experimental city, modeled after the German "White City" version created at Stuttgart in 1928. For the Exposition, Hoffmann designed four different houses, of different sizes and designs, all simple and practical. They were made of brick covered by plaster. One innovative feature added by Hoffmann was a glass-enclosed stairway on the exterior of each house, which made the interior of the house larger and gave variety to the facade. Another modern feature, borrowed from Corbusier, was a roof terrace on each residence. [21]

-

Sonya Knips House (1924–25)

-

Entrance to Knips House (1924–25)

-

Werkbund model house, Veitingergasse 85 (1930–32)

Austria Pavilion at the Venice Biennale (1934)[edit]

The last major work of Hoffmann before the Second World War was Austria Pavilion at the 1934 Venice Biennale. The building was of an extreme simplicity, in a U form, with one side slightly longer than the other. The walls were made of crepi in horizontal stripes. The original entrance portal and sculptural decoration designed by Hoffmann were never made due to budget difficulties, but their absence added to the final priority of structure. The building was unused after 1938, when Nazi Germany took over Austria, but was restored in 1984 to its original appearance. [22]

-

Austria Pavilion for the Venice Biennale (1934)

Later Years and Death (1939–1956)[edit]

In 1936 he became Professor Emeritus at the Fine Arts, essentially retired, though he continued to work with his earlier students. In 1937 he presented a model interior, "The Boudoir of a great actress", at the Paris International Exposition of 1937, and designed new interiors for the Hotel Imperial in Vienna. In 1940, he redesigned the interior of the Meissen factory and offices in Vienna. After Austria united with Germany, he redesigned the former German Embassy in Vienna to serve as new headquarters of the German Army in Austria. During the War, he made more than eighty projects for houses and other buildings, but there is no record if any were constructed. [12]

In 1945, following the War, Hoffmann rejoined the Vienna Secession, the artistic movement that he, Klimt and Otto Wagner had dramatically quit in 1905. He was elected President of the Secession from 1948 to 1950. Between 1949 and 1953, based on his experience before the War, he designed three large public housing projects in Vienna. [12]

He died on May 7, 1956, at the age of eighty-five, at his apartment at 33 Salesianergasse in Vienna. [12] As an acknowledgement of his contribution to modern architecture, the city of Vienna gave him an honorary grave at the Vienna Central Cemetery (Wiener Zentralfriedhof). A picture is in one of the external links.

Teaching at Kunstgewerbeschule[edit]

Although he said little to his students, Hoffmann was a highly esteemed and admired teacher. He tried to bring out the best in each member of his class by means of challenging assignments, which were occasionally work on real commissions.[23] Where he detected talent among young artists he was willing or eager to promote it; Oskar Kokoschka, Egon Schiele and Le Corbusier were the most prominent beneficiaries of his benevolence towards a promising next generation; others strongly influenced by his aesthetic included the American designers Edward H. and Gladys Aschermann and Louise Brigham. German designer Anni Schaad was another of his students. Le Corbusier was offered a job in his office, Schiele was helped financially and Kokoschka was given work in the Wiener Werkstätte. As a member of the international jury for the competition to design a palace for the League of Nations at Geneva in 1927, Hoffmann belonged to the minority who voted for Le Corbusier's project, and the latter always spoke with admiration of his Viennese colleague. Hoffmann had voted for the union of Austria with Germany and, as noted in Tim Bonyhady's "Good Living Street. The fortunes of my Viennese family" (2011), the architect was admired by the Nazis who appointed him a Special Commissioner for Viennese Arts and Crafts and commissioned him to remodel the former German embassy building into the "Haus der Wehrmacht" for army officers. Following its use by the British Government from 1945 to 1955 it was demolished. Hoffmann died in Vienna, aged 85.

Critical reception and posthumous reputation[edit]

His international exhibition work helped to make his name widely known, and many distinguished contributors to the Festschrift on his 60th birthday acclaimed him as a master.[citation needed] Honours bestowed on him included the cross of a commander of the Légion d'honneur and the Honorary Fellowship of the American Institute of Architects. The critic Henry-Russell Hitchcock in 1929 wrote, "In Germany as well as in Austria, Hoffmann's manner has profoundly influenced the New Tradition".[citation needed] Only three years later, however, when he published The International Style together with Philip Johnson, Hitchcock no longer mentioned Hoffmann's name. Siegfried Giedion in his influential Space, Time and Architecture did not do justice [clarification needed] to Hoffmann's oeuvre because it would not fit easily into his polemically simplified version of architectural history.[citation needed]

Despite honours and praise on the occasions of Hoffmann's 80th and 85th birthdays, he was virtually forgotten by the time of his death. Although his true stature and contribution were acknowledged by such masters as Alvar Aalto, Le Corbusier, Gio Ponti and Carlo Scarpa,[citation needed] the younger generation of architects and historians ignored him.

The process of rediscovery and reappraisal began in 1956 with a small book by Giulia Veronesi, and gained momentum during the 1970s with a number of exhibitions and smaller publications. [where?][citation needed] In the 1980s several monographs were published and major exhibitions held. [where?][citation needed] Imitations of his style also began to appear, and replicas of his furniture, fabrics, and of some objects he had designed became commercial successes, while original pieces and drawings from his hand fetched record prices in the auction-rooms. [where?][citation needed]

Legacy in America[edit]

Josef Hoffmann's son, Wolfgang Hoffmann, together with his father's former student Pola Weinbach Hoffmann (later Pola Stout), emigrated to New York in 1925 and made significant contributions to American modernism.[24]

Awards and honors[edit]

- 1950: Grand Austrian State Prize for Architecture

- 1951: Honorary Doctorate of the Vienna University of Technology[25]

- Honorary Doctor of the Dresden University of Technology[26]

In Brtnice the birthhouse of Josef Hoffmann was transferred into a permanent exhibition centre after an initial exhibition of his work in 2006. It is administered by the Moravian Gallery in Brno. The Brtnice article features a picture of the museum.

Selected architecture works[edit]

- 1900–1911 Designer for Hohe Warte Artists' Colony

- 1900–1901 Double House for Koloman Moser and Carl Moll

- 1904 Sanatorium Purkersdorf

- 1905–1906 House for the writer Richard Beer-Hofmann in Vienna

- 1905–1911 Stoclet Palace in Brussels, Belgium

- 1907 Interior decoration of Kabarett Fledermaus in Vienna

- 1909–1911 Ast Residence in Vienna

- 1913–1915 Skywa-Primavesi Residence in Vienna

- 1913–1914 Country house for Otto Primavesi (www.primavesi.eu) in Kouty nad Desnou (Winkelsdorf), Moravia (destroyed by fire in 1922[27])

- 1919–1924 House for Sigmund Berl in Bruntal, Moravia

- 1920–1921 Villa for Fritz Grohmann in Vrbno pod Pradedem, Moravia

- 1923–1925 Urban Klosehof Housing Complex

- 1924–1925 Villa Knips in Vienna, made for Sonja Knips

- 1930–1932 Four row houses for the Viennese Werkbund's settlement (Werkbund Siedlung)

- 1934: Design of the Viktorin-Werke branch at Burgring 3, Vienna with Oswald Haerdtl[28]

- 1934 Austrian pavilion at the Venice Biennale

A complete list of his architectural works is in the German-language version of this article, with details and photos.

Selected furniture works[edit]

- 1904 Purkersdorf Armchair

- 1905 Sitzmaschine Armchair

- 1905 Kunstschau Armchair

- 1905–1910 Stoclet Palace Armchair

- 1907 Fledermaus Chair

- 1907 Seating set "Buenos Aires" (produced by J&J Kohn as 675C/F/S)

- 1908 Siebenkugelstuhl Chair

- 1908 Armloffel Chair

- 1910 Kubus Armchair

- 1910 Club Armchair

- 1911 Haus Koller Chair

Gallery[edit]

1899 to 1910[edit]

-

Bergerhöhe 1 (1899)

-

Untere Hauptstraße 4–6 (1900)

-

Villa Spitzer (1903)

-

House Moser-Moll (1903)

-

Protestant church (1903)

-

Union hotel (1903)

-

Sanatorium Purkersdorf (1905)

-

House for Beer-Hofmann (1906)

-

House Moll II (1906)

-

Cabaret "Fledermaus" (1907)

-

Seilerstätte 24 (1908)

-

Tomb for Emil Zuckerkandl (1908)

1910 to 1954[edit]

-

Steinfeldgasse 2 (1911)

-

Stoclet Palace (1911)

-

Tomb for Gustav Mahler (1911)

-

Tomb for Paul Wittgenstein (1912)

-

Pfarrgasse 15 (1913)

-

Kaasgrabengasse 30-32 (1914)

-

Kaasgrabengasse 36–38 (1914)

-

Suttingergasse 12–14 (1914)

-

Suttingergasse 16–18 (1914)

-

Villa Primavesi (1915)

-

Tschechien (1921)

-

House for Sonja Knips (1924)

-

Klose-Hof (1925)

-

Winarsky-Hof (1925)

-

Monument for Otto Wagner (1930)

-

Laxenburger Straße 94 (1932)

-

Veitingergasse 79–85 (1932)

-

Austrian Pavilion at Venice Biennale (1934)

-

Arbeitergasse 1-7 / Spengergasse (1939)

-

Blechturmgasse 23–27 (1950)

-

Silbergasse 2–4 (1952)

-

Heiligenstädter Straße 129 (1954)

References[edit]

- ^ "Josef Hoffmann". Collection. Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d Sarnitz 2017, p. 12.

- ^ Pg. 79, Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture: A Critical History. Thames & Hudson. 1980, 1985, 1992.

- ^ Sarnitz 2017, p. 15.

- ^ Sarnitz 2017, p. 16-17.

- ^ a b Sarnitz 2017, p. 16.

- ^ "Jugendstil Waldkirchlein St. Aegyd". Mostviertel (in German). Retrieved 2023-05-03.

- ^ "Vienna Secession history by Senses-ArtNouveau.com". Archived from the original on 2018-01-30. Retrieved 2007-05-22.

- ^ MoMA.org | The Collection | Josef Hoffmann. (Austrian, 1870-1956)

- ^ All Josef Hoffmann: Tea service (2000.278.1-.9) | Works of Art | Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Grrr.nl. "Rundes Modell - Josef Hoffmann". www.stedelijk.nl. Retrieved 2023-05-03.

- ^ a b c d Sarnitz 2016, p. 94.

- ^ Cattermole, Paul (2008). Architectural Excellence: 500 Iconic Buildings. Firefly Books. p. 243. ISBN 978-1-5540-7358-0.

- ^ Pg. 81, Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture: A Critical History. Thames & Hudson. 1980, 1985, 1992.

- ^ Dr Harry Francis Mallgrave, Modern Architectural Theory: a historical survey, 1673-1968. Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-79306-8

- ^ Sarnitz 2016, pp. 55–61.

- ^ a b Sarnitz 2016, p. 54-61.

- ^ Sarnitz 2016, p. 66-67.

- ^ Sarnitz 2016, p. 68-71.

- ^ a b Sarnitz 2016, p. 83.

- ^ Sarnitz 2016, pp. 86–89.

- ^ Sarnitz 2016, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Lillian Langseth Christensen: A Design for Living. Vienna in the Twenties, 1987.

- ^ Wilson, Richard Guy; Pilgrim, Dianne H.; Tashjian, Dickran; Brooklyn Museum (1986). The Machine Age in America 1918–1941. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-1421-2.

- ^ TU Wien: Ehrendoktorate Archived 2016-02-21 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ Verzeichnis der Ehrenpromovenden der TH/TU Dresden

- ^ "The country house of the Primavesi family in Winkelsdorf". Archived from the original on 2009-01-05. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ^ "Viktorin, Robert V. industrialist". ÖSTERREICHISCHES BIOGRAPHISCHES LEXIKON (ÖBL) (in German). Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. 2003. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

ISBN 978-3-7001-3213-4

Bibliography[edit]

- Stefan Üner: Josef Hoffmann, in: Parnass, vol. 1, Vienna 2022, p. 166–167

- Sarnitz, August (2016). Josef Hoffmann, L'univers de la beauté (in French). Cologne: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8365-5038-3.

- Sarnitz, August (2017). Josef Hoffmann. In the Realm of Beauty. Cologne: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-5591-1.

- Fahr-Becker, Gabriele (2008). Wiener Werkstätte: 1903‒1932. Cologne: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-3773-3.

- Sekler, Eduard (1982). Josef Hoffmann. Das Architektonische Werk; Monographie und Werkverzeichnis. Salzburg: Residenz. ISBN 3-7017-0306-X.

- Vives Chillida, Julio (2008). Josef Hoffmann y Jacob & Josef Kohn en la Kunstschau Wien de 1908, (La pequeña casa de campo: una efímera obra de arte total). Lulu.com (print on demand). ISBN 978-1-4092-0239-4.

- Huey, Michael, ed. (2003) Viennese Silver. Modern Design 1780–1918, exhibition catalogue for the Neue Galerie New York, Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern. ISBN 978-3-7757-1317-7.

- Witt-Dörring, Christian, ed. (2006) Josef Hoffmann Interiors 1902–1913, exhibition catalogue for the Neue Galerie New York, Prestel Verlag, New York. ISBN 978-3-7913-3710-4.

External links[edit]

Quotations related to Josef Hoffmann at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Josef Hoffmann at Wikiquote Media related to Josef Hoffmann at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Josef Hoffmann at Wikimedia Commons- Papers of Josef Franz Maria Hoffmann at the Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Accession No. 850997. Correspondence, manuscripts, photographs and other papers of the Austrian designer and architect, Josef Hoffmann, document his involvement in the arts and crafts movement and his writings in art education. The bulk of the papers date to the 1920s and 1930s.

- Lamps and furnitures designed by Josef Hoffmann for the Wiener Werkstaette

- Fabrics designed by Josef Hoffmann for the Wiener Werkstatte

- A 40 min video by WOKA (Wolfgang Karolinsky), Josef Hoffmann and the Wiener Werkstaette, from 1991

- Josef Hoffmann's grave at the Wiener Zentralfriedhof

- 1870 births

- 1956 deaths

- People from Brtnice

- People from the Margraviate of Moravia

- Moravian-German people

- Austrian people of Moravian-German descent

- Modernist architects from Austria

- Austrian architects

- Austrian designers

- Art Deco architects

- Vienna Secession architects

- Wiener Werkstätte

- Academy of Fine Arts Vienna alumni

- Burials at the Vienna Central Cemetery