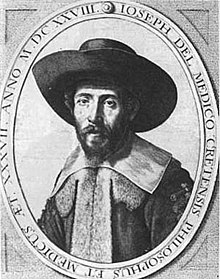

Joseph Solomon Delmedigo

Joseph Solomon Delmedigo (or Del Medigo), also known as Yashar Mi-Qandia (Hebrew: יש"ר מקנדיא) (16 June 1591 – 16 October 1655), was a rabbi, author, physician, mathematician, and music theorist.[1]

Born in Candia, Crete, a descendant of Elia del Medigo, Joseph Solomon or Yashar Mi-Qandia is a member of Del Medigo de'Candia lineage from the Geiger family of Germany that settled first in Crete and then in Italy.[2][3] Eventually, he moved to Padua, Italy, studying medicine and taking classes with Galileo in astronomy. After graduating in 1613 he moved to Venice and spent a year in the company of Leon de Modena and Simone Luzzatto. From Venice he went back to Candia and from there started traveling in the near East, reaching Alexandria and Cairo. There he went into a public contest in mathematics against a local mathematician. From Egypt he moved to Istanbul, there he observed the comet of 1619. After Istanbul he wandered along the Karaite communities in Eastern Europe, finally arriving at Amsterdam in 1623. He died in Prague. Yet in his lifetime wherever he sojourned he earned his living as a physician and or teacher. His only known works are Elim (Palms), dealing with mathematics, astronomy, the natural sciences, and metaphysics, as well as some letters and essays.

As Delmedigo writes in his book, he followed the lectures by Galileo Galilei, during the academic year 1609–1610, and was accorded the rare privilege of using Galileo's own telescope. In the following years he often refers to Galilei as "rabbi Galileo," an ambiguous phrase which may simply mean "my master, Galileo." (Delmedigo never calls him "our teacher and master, Rabbi Galileo," which would be the typical way of referring to an actual rabbi.) Elijah Montalto, physician of Maria de Medici, is also mentioned as one of his teachers.

Works[edit]

Elim (1629, published by Menasseh ben Israel, Amsterdam) is written in Hebrew, in response to 12 general and 70 specific religious and scientific questions sent to Delmedigo by a Karaite Jew, Zerach ben Natan from Troki (Lithuania). The format of the book is taken from the number of fountains and palm trees at Elim in the Sinai Peninsula, as given in Numbers, xxxiii, 9: since there are 12 fountains and 70 palm trees at Elim, Delmedigo divided his book into twelve major problems and seventy minor problems. The book, however, was heavily censored, so only four of the original twelve major problems appeared in the published work.[4] The subjects discussed include astronomy, physics, mathematics, medicine, and music theory. In the area of music, Delmedigo discusses the physics of music including string resonance, intervals and their proportions, consonance and dissonance. Delmedigo argued that the Jews did not take part in the Scientific Revolution because of Ashkenazi exclusive intellectual interest in the Talmud, whereas the Sepharadim and the Karaites were more interested in natural philosophy and philosophy in general. He called the Jews to reclaim their prominence in philosophy and to incorporate into the non-Jewish surrounding via the exploration of natural sciences.

Some parts of the book were as follows:

- Ma'ayan Chatum (Closed or Sealed Fountain - Heb. מעין חתום) is the second part of Sefer Elim, containing the 70 questions and answers.

- Ma'ayan Ganim (Fountain of the Gardens - Heb. מעין גנים) is a continuation of Sefer Elim, consisting of the following short treatises: on trigonometry, on the first two books of the Almagest, on astronomy, on astronomical instruments, on Kabbalah (mainly the Ari) and the supernatural, on astrology, on algebra, on chemistry, on the aphorisms of Hippocrates, on the opinion of the ancients concerning the substance of the heavens, on the astronomy of the ancients, who considered the motion of the higher spheres due to spirits (Delmedigo shows that their motion is similar to that of the earth), on the principles of religion, and mathematical paradoxes.

- Chukkot Shamayim is a part of Mayan Ganim dealing with the first two books of the Almagest.

- Gevurot Hashem is a treatise on astronomy.

He also wrote a defense of the Kabbalah called Matzreif LaChachma (Heb. מצרף לחכמה) against the attack upon it by his great grandfather Eliyahu Delmedigo. In the preface of the book the publisher writes that the author himself admitted once that when he was young (18 years old when he went to study in the university of Padua) he used to mock the Kabbalah and fiercely opposed those who studied it, but when he turned twenty seven he had a change of heart when he met two great philosophers, R' Yaakov ibn Nachmias and R' Shlomo Aravi, who were also firm adherents of the Kabbalah and they showed him how closely it resembles the philosophy of Plato, since then there was a renewed spirit within him.[5]

Descendants[edit]

Some of Delmedigo's descendants settled in Byelorussia and took on the Surname Gorodinsky (after the town of Gorodin). A member of this family, Mordechai Gorodinsky (later hebraized to Nachmani) was one of the founders of the Israeli city of Rehovot.[citation needed]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Yashar is an acronym that includes both his two Hebrew initials, Yosef Shlomo, and his profession, rofe ('physician'). Yashar from Candia (יש"ר מקנדיה) is also a Hebrew pun, since Yashar means straight, as in 'the straight [man] from Candia'. The drawing (reproduced above to the right) on the frontispiece of his only printed work gives his name simply as Ioseph Del Medico 'Cretensis', or 'Joseph [of] the Physician, from Crete, Philosopher and Physician'. It is hard to determine which of the two, the family name Delmedigo on the one hand or the profession (physician), existed in the first place, giving origin to the other. The Hebrew title page to Sefer Elim gives his occupations specifically as a "complete" rabbi (shalem; this may mean that he had some sort of official smicha), philosopher, physician, and "nobleman" (aluf).

- ^ Eliahu del Medigo, the Last Averroist, by Josep Puig Montada, EXCHANGE AND TRANSMISSION ACROSS CULTURAL BOUNDARIES 2005, The Institute for Advanced Studies, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, ISBN 978-965-208-188-9

- ^ Geiger family Archive, 1874, founders of Reform Judaism. See ‘Ibn Rushd al-ḥafîdh,’ in J. L. Delgado (ed.), Biblioteca de al-Andalus, IV, Almeria 2006, no. 1006, pp. 517– 617; and Ludwig Geiger, Abraham Geiger: Leben und Werk für ein Judentum in der Moderne, Berlin 2001.

- ^ J. d'Ancona, "Delmedigo, Menasseh ben Israel en Spinoza," Bijdragen en Mededeelingin van het Genootschap voor de Joodsche Wetenschap in Nederland 5 (1940): 105-152.

- ^ The early Acahronim, The Artscroll history series, p. 157

Further reading[edit]

- Adler, Jacob. "Epistemological categories in Delmedigo and Spinoza". Studia Spinozana 15 (1999) 205-227.

- ______. "J.S. Delmedigo as Teacher of Spinoza: The Case of Noncomplex Propositions". Studia Spinozana 16 (2008), 177-83.

- _____. "Joseph Solomon Delmedigo, Student of Galileo, Teacher of Spinoza". Intellectual History Review 23(2013), 141-57.

- Encyclopaedia Judaica (Jerusalem, 1972), Vol. 5, 1477-8

- Barzilay, Isaac, Yoseph Shlomoh Delmedigo (Yashar of Candia): His Life, Work and Times, Leiden, 1974

- Israel, Jonathan I. Spinoza, Life & Legacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press 2023. ISBN 9780198857488

- Langermann, Tzvi, An Alchemical Treatise Attributed to Joseph Solomon Delmedigo, Aleph: Historical Studies in Science and Judaism Volume 13, Number 1, 2013, pp. 77–94 [1]

- Don Harrán. "Joseph Solomon Delmedigo", Grove Music Online, ed. L. Macy (accessed February 5, 2005), grovemusic.com Archived 2008-05-16 at the Wayback Machine (subscription access).

- Ben-Zaken, Avner (2010). "Transcending Time in the Scribal East". Cross-Cultural Scientific Exchanges in the Eastern Mediterranean 1560-1660. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 76–103.

External links[edit]

- Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) article on Delmedigo

- Encyclopaedia Judaica (2007) article on Delmedigo

- The Gorodinsky Family