KV57

| KV57 | |

|---|---|

| Burial site of Horemheb | |

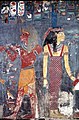

The burial chamber of Horemheb, showing the unfinished decoration and his sarcophagus | |

| Coordinates | 25°44′23.6″N 32°36′02.6″E / 25.739889°N 32.600722°E |

| Location | East Valley of the Kings |

| Discovered | 22 February 1908 |

| Excavated by | Edward R. Ayrton (1908) Geoffrey Thorndike Martin (2006-7) |

| Decoration | Horemheb making offerings to gods and goddesses; Book of Gates |

← Previous KV56 Next → KV58 | |

Tomb KV57 is the royal tomb of Horemheb, the last pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty and is located in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt.

The tomb was located by Edward Ayrton in February 1908 for Theodore Davis. Due to its location in the valley floor, the tomb was filled with debris that had washed down during occasional flash-flooding. The tomb is markedly different from previous Eighteenth Dynasty royal tombs as it has a straightened axis, and has painted reliefs instead of murals; the Book of Gates also appears for the first time. The king's red granite sarcophagus was found with its lid broken, though otherwise intact. The tomb contained the remains of several burials, none of them conclusively belonging to Horemheb.

Layout[edit]

The tomb consists of a descending entrance stair, a sloping passageway leading to another descending stair, and another passageway that ends in a well shaft. Beyond the well chamber is the first pillared hall. Cut into the floor on the left side of the pillared hall is a staircase, originally sealed, leading to another descending passage and, via another flight of steps, the antechamber. Beyond this room is the pillared burial chamber, surrounded by storerooms. The floor at the far end of the burial chamber is lowered to create a crypt.[1]

The layout is transitional in form between the 'dog-leg' style of earlier Eighteenth Dynasty tombs and the straight axis tombs of the Nineteenth Dynasty;[2] more precisely this layout is known as a jogged axis. The steep descent of the earlier style is combined with the large straight corridors prevalent in the later style. The pillared hall is more square than previous iterations, as it would continue to be in future royal tombs. However, some novel features occur in this tomb that are not seen again, such as the ramp at the top of the stairs leading to the crypt around the sarcophagus, the second set of stairs in this area, and the burial below the floor in one of the storerooms.[1]

Location, discovery and investigation[edit]

KV57 was discovered in February 1908 by Edward Ayrton who was excavating on behalf of Theodore Davis. After the discovery and excavation of the 'Gold Tomb' (KV56) in January 1908,[3] the clearance of the valley floor continued westward, following the rockface.[2]

On 25 February 1908 signs of a tomb were encountered and a day later the stairway was exposed, choked almost entirely with sand and debris. Davis recounts that they dug with their hands and, after clearing enough to admit a person, Ayrton crawled inside in order to find out whose tomb it was. He encountered a hieratic inscription naming Horemheb on the wall some distance inside.[4] A more formal entry occurred on 29 February after further excavation;[4] the party consisted of Davis, Ayrton, Harold Jones, Max Dalison, and Arthur Weigall.[5]

The group slid over the sand and stones that still partially filled the corridors until they reached the edge of the well chamber which contained exquisite decoration.[4] Weigall recounts:

Holding the lamps aloft, the surrounding walls were seen to be covered with wonderfully preserved paintings... Here Horemheb was seen standing before Isis, Osiris, Horus, and other gods; his cartouches stood out boldly from amidst the elaborate inscriptions. The colours were extremely rich, and, though there was so much to be seen ahead, we stood there for some minutes, looking at them with a feeling much akin to awe.[5]

After admiring the paintings, they pressed further into the tomb. The well was found to be partially filled with debris and was crossed with the aid of a ladder. The decorated wall on the far side of the well had been broken through by ancient robbers who were not fooled by the concealed entrance. The group continued through into the pillared hall, noting the sections of collapsed ceiling, before continuing into the antechamber where once again they were struck by the fresh colours of the painted decoration. In the burial chamber, the unfinished nature of the decoration drew attention, as did the crumbling columns and fallen sections of ceiling. In addition to fallen limestone, the floor was littered with the remains of the ransacked burial, mostly wooden figures, and some plant material.[5] The open but intact sarcophagus standing in the lower crypt area of the burial chamber attracted immediate attention; it was found to contain a skull and an assortment of bones. More human remains were encountered in the side chambers, including an interment in a sunken chamber inside one of the rooms. Having made a quick exploration, the party retreated back above ground, as the hot, airless tomb did not permit a longer stay.[5]

Little is known of the actual excavation and clearance of the tomb as Davis mentions Ayrton had prepared an "exhaustive report" which could not be included due to the size of Davis' publication,[4] and has since been lost.[6]

Re-excavation[edit]

Between 2006 and 2007 the tomb was re-excavated in a project led by Geoffrey Thorndike Martin. The work cleared the tomb of debris left by the original excavation, which had piled it into side rooms instead of removing it from the tomb.[7]

Contents[edit]

The largest object still remaining in the tomb was the pharaoh's red granite sarcophagus, which Davis described as "one of the most beautiful ever found."[4] It was made in the same style as those of Akhenaten, Tutankhamun, and Ay, in the form of a rectangular pylon complete with cavetto cornice and torus moulding, and with protective goddesses on each corner.[6] The lid had been removed in antiquity and had snapped along a mended break, indicated by the presence of butterfly cramps.[1] The sarcophagus appeared to be supported by six wooden figures of deities, which were placed into niches in the floor.[2]

Much of what little else remained was broken and fragmented due to looting in antiquity. The coffins were represented by small pieces of inscribed cedar wood coated in resin. The alabaster canopic chest, carved from a single block[8] with additional portrait-headed stoppers, had been smashed apart.[1] Of the contents, only the intestines were noted; the packet had been formed into the shape of a miniature mummy.[8] Parts of four miniature lion-headed embalming tables were also encountered. Life-sized 'guardian statues', broken off at the knee and missing faces or limbs were among the funerary figures recovered. The heads of hippo-headed, cow-headed, and lioness-headed couches were found, as were three large Anubis statues similar to Tutankhamun's Anubis shrine. Other wooden remains included statues of a leopard, falcons, a swan, and a germinating Osiris figure.[8][1] Several wooden statues made it onto the antiquities market and are now in the British Museum.[1] Other finds included magical bricks, models boats, parts of fixed and folding chairs, pall rosettes, a head rest, beads, and alabaster vases. A single non-royal Eighteenth Dynasty canopic jar with a human-headed stopper was found; it bears a hieratic inscription naming a certain 'Sanoa.'[8][1]

Human remains[edit]

Grafton Elliot Smith conducted a cursory examination of the human remains and determined that the remains from the side chambers were those of two women, the skulls on the floor of the burial chamber belonged to a man and two women, and the sarcophagus contained the bones of a single person of uncertain sex.[4] Their identities are unknown but they may have been minor members of the royal family who were not moved when the royal burial was disassembled, remnants of a possible cache, or intrusive burials dating to the Third Intermediate Period.[9] Nicholas Reeves suggests that Horemheb is indeed among the human remains found in KV57. He posits that, based on the ink graffiti, the king's mummy was removed and rewrapped during the Wehem Mesut. During this restoration the body was separated from its coffin, which was later used for the reburial of Ramesses II, before being returned to the tomb along with other royal mummies, forming a third royal cache.[10]

Decoration[edit]

As with earlier tombs, the decoration is confined to three walls of the well chamber, the antechamber, and the burial chamber, though for the first time in a royal tomb, the walls are decorated with painted bas-reliefs instead of simpler mural paintings. Much of the decoration in the burial chamber is unfinished, preserving the process from gridded preliminary sketches, corrections, carving, and finally painting. The use of colour is particularly striking, with the brightly painted figures and hieroglyphs standing out against the blue-grey background.[1] The excavators were likewise struck by the beauty of the decoration, as Maspero writes:

Our first impression on entering these rooms is one of unmitigated admiration. The colours are still so fresh, and the play of tones so harmonious though so bright, the arrangement of the figures on the walls is so well balanced that we can feel nothing but pleasure and satisfaction.[11]

The reliefs in the well chamber and antechamber continue the tradition started in the tomb of Thutmose IV, depicting Horemheb making offerings to gods and goddesses associated with the afterlife; however Nut is here replaced by Isis. The burial chamber decoration uses scenes from the Book of Gates instead of the Amduat for the first time.[1]

Graffiti[edit]

The presence of black ink graffiti inscriptions were noted at the time of excavation,[5] and were recorded by Alan Gardiner some time later. The first inscription, presumably on one of the door posts,[9] reads:

Written in Year 4, 4 Akhet 22, by the Army-Scribe Butehamun, after he came to cause the order to be carried out in the pr-ḏt in the tomb of King Djoserkheper(u)re Setepenre, l.p.h.[12]

On the left side of the door thickness:

Written by the scribe of the general, Kysen.[9]

And lower down on the same wall:

The scribe Butehamun; the king's scribe Djehutymose.[9]

The graffiti on the right side of the door thickness[9] reads:

Year 6, 2(?) Akhet 12, Day of removing(?)/investigating(?) the burial(?) of King Djoserkheper(u)re Setepenre, by the Vizier, General and Chief of the... Herihor.[12][10]

This final inscription has been interpreted as recording the first restoration of the burial, or the less likely scenario of the transfer of the body of Ay from his mutilated tomb to KV57.[9]

Gallery[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (1996). The Complete Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Treasures of Egypt's Greatest Pharaohs (2000 ed.). London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. pp. 130–133. ISBN 978-0-500-28403-2. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ a b c Ayrton, Edward R. (1908). "Recent Discoveries in the Biban el Moluk of Thebes". Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology. London: Society of Biblical Archaeology. pp. 116–117.

- ^ Davis, Theodore M.; Maspero, Gaston; Ayrton, Edward; Daressy, George (1908). The Tomb of Siptah; The Monkey Tomb and the Gold Tomb (PDF). London: Archibald Constable & Co. Ltd. pp. 31–32. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Davis, Theodore M.; Maspero, Gaston; Daressy, George (1912). The Tombs of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamanou (Duckworth 2001 reprint ed.). London: Archibald Constable & Co. Ltd. pp. 1–3. ISBN 0-7156-3072-5.

- ^ a b c d e Weigall, Arthur E. P. B. (1911). The Treasury Of Ancient Egypt: Miscellaneous Chapters on Ancient Egyptian History and Archaeology. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons. pp. 227–236. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ a b Romer, John (1981). Valley of the Kings. London: Book Club Associates. pp. 223–228.

- ^ van Dijk, Jacobus (2008). "New Evidence on the Length of the Reign of Horemheb". Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt. 44: 193–200. ISSN 0065-9991.

- ^ a b c d Davis, Theodore M.; Maspero, Gaston; Daressy, George (1912). The Tombs of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamanou (Duckworth 2001 reprint ed.). London: Archibald Constable & Co. Ltd. pp. 97–109. ISBN 0-7156-3072-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Reeves, C. N. (1990). Valley of the Kings: the decline of a royal necropolis. London: Kegan Paul International Ltd. pp. 75–79. ISBN 0-7103-0368-8.

- ^ a b Reeves, Nicholas (2017). "The coffin of Ramesses II". In Amenta, Alessia; Guichard, Helene (eds.). Proceedings First Vatican Coffin Conference 19–22 June 2013 Volume 2. Edizioni Musei Vaticani. pp. 425–438. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Davis, Theodore M.; Maspero, Gaston; Daressy, George (1912). The Tombs of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamanou (Duckworth 2001 reprint ed.). London: Archibald Constable & Co. Ltd. pp. 61–95. ISBN 0-7156-3072-5.

- ^ a b Peden, Alexander J. (2001). The Graffiti of Pharaonic Egypt: Scope and Roles of Informal Writings (c. 3100–332 B.C.). Brill. pp. 207–208. ISBN 978-90-04-12112-6. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

External links[edit]

- Theban Mapping Project: KV57 includes detailed maps of the tomb.