Khwarazmian Empire

Khwarazmian Empire خوارزمشاهیان Khwārazmshāhiyān | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1077–1231 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Territory of the Khwarazmian Empire c. 1215, on the eve of the Mongol conquests | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Gurganj (1077–1212) Samarqand (1212–1220) Ghazna (1220–1221) Tabriz (1225–1231) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Largest city | Shahr-e Ray | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Persian (official, court, spoken)[1][2] Arabic (theology, numismatics[3]) Kipchak Turkic (dynastic, spoken)[4] Oghuz Turkic (spoken)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Khwarazmshah | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1077–1096/7 | Anushtegin Gharchai | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1220–1231 | Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | c. 1077 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1219–1221 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1230 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1231 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1210 est.[6] or | 2,300,000 km2 (890,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1218 est.[7] | 3,600,000 km2 (1,400,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5,000,000 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Dirham | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

The Khwarazmian or Khwarezmian Empire[note 2] (English: /kwəˈræzmiən/)[9] was a culturally Persianate, Sunni Muslim empire of Turkic mamluk origin.[10][11] Khwarazmians ruled large parts of present-day Central Asia, Afghanistan, and Iran from 1077 to 1231; first as vassals of the Seljuk Empire[12] and the Qara Khitai (Western Liao dynasty),[13] and from circa 1190 as independent rulers up until the Mongol conquest in 1219–1221.

The Khwarazmian Empire eventually became "the most powerful and aggressively expansionist empire in the Persian lands", defeating the Seljuk Empire and the Ghurid Empire, even threatening the Abbasid caliphate. In the beginning of the 13th century, the empire is thought to have become the greatest power in the Muslim world.[14] It is estimated that the empire spanned an area of 2.3 to 3.6 million square kilometres.[15][16] The empire, which was modelled on the preceding Seljuk Empire, was defended by a huge cavalry army composed largely of Kipchak Turks.[17]

The Khwarezmian Empire was the last Turco-Persian Empire before the Mongol invasion of Central Asia. In 1219, the Mongols under their ruler Genghis Khan invaded the Khwarazmian Empire, successfully conquering the whole of it in just two years. The Mongols exploited existing weaknesses and conflicts in the empire, besieging and plundering the richest cities, while putting its citizens to the sword in one of the bloodiest wars in human history.

The date of the founding of the state of the Khwarazmshahs remains debatable. The dynasty that ruled the empire was founded by Anush Tigin (also known as Gharachai), initially a Turkic slave of the rulers of Gharchistan, later a Mamluk in the service of the Seljuks. However, it was Ala ad-Din Atsiz (r. 1127–1156), descendant of Anush Tigin, who achieved Khwarazm's independence from its neighbors.

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

The title of Khwarazmshah was introduced in 305 AD by the founder of the Afrigid dynasty and existed until 995. After a short interval, the title was reinstated. During the uprising in Khwarazm in 1017, rebels killed the then Khwarazmian ruler Abu'l-Abbas Ma'mun and his wife Khurra-ji, the sister of Ghaznavid sultan Mahmud.[18] In response, Mahmud invaded the region to quell the rebellion. He later installed a new ruler and annexed a portion of Khwarazm. As a result, Khwarazm became a province of the Ghaznavid empire and remained so until 1034.[19]

In 1077, the control of the region, which previously belonged to the Seljuqs from 1042 to 1043, passed into the hands of Anushtegin Gharchai, a Turkic mamluk commander of the Seljuqs.[20] In 1097, the Khwarazm governor of the Turkic origin Ekinchi ibn Qochqar declared independence from the Seljuqs and proclaimed himself the shah of Khwarazm. After a short period of time, however, he was killed by several Seljuq amirs that had risen in revolt. He was subsequently replaced with Anush Tigin Gharachai's son, Qutb al-Din Muhammad by the Seljuqs, who had reconquered the region. Thus, Qutb al-Din became the first hereditary Khwarazmshah.[21]

Rise[edit]

Anushtegin Gharachai[edit]

Anushtegin Gharachai was a Turkic[note 3] mamluk commander of the Seljuqs[25] and the governor of Khwarazm from approximately 1077 until 1097. He was the first member of his family to rule Khwarazm, and the namesake for the dynasty that would rule the province in the 12th and early 13th centuries.

Anushtegin was put in command together with his master Gumushtegin Bilge-Beg in 1073 by the Seljuq sultan Malik-Shah I to retake territory in northern Greater Khorasan that the Ghaznavids had seized.[26] He was subsequently made the sultan's tasht-dar (Persian: "keeper of the royal vessels"), and, as the revenues from Khwarazm were used to pay for the expenses incurred by this position, he was made governor of the province. The details of his tenure as governor are unclear, but he died by 1097 and the post was briefly given to Ekinchi bin Qochqar before being transferred to his son, Qutb al-Din Muhammad.

Ala ad-Din Atsiz[edit]

Atsiz gained his position following his father Qutb al-Din's death in 1127. During the early part of his reign, he focused on securing Khwarazm against nomad attacks. In 1138, he rebelled against his suzerain, the Seljuq sultan Ahmad Sanjar, but was defeated in Hazarasp and forced to flee. Sanjar installed his nephew Suleiman Shah as ruler of Khwarazm and returned to Merv. Atsiz returned, however, and Suleiman Shah was unable to hold on to the province. Atsiz then attacked Bukhara, but by 1141 he again submitted to Sanjar, who pardoned him and formally returned control of Khwarazm over to him. The same year that Sanjar pardoned Atsiz, the Kara Khitai under Yelü Dashi defeated the Seljuqs in the Battle of Qatwan (1141), near Samarqand. Atsiz took advantage of the defeat to invade Khorasan, occupying Merv and Nishapur. Yelü Dashi, however, sent a force to plunder Khwarazm, forcing Atsiz to pay an annual tribute.[27] In 1142, Atsiz was expelled from Khorasan by Sanjar, who invaded Khwarazm in the following year and forced Atsiz back into vassalage, although he continued to pay tribute to the Kara Khitai until his death. Sanjar undertook another expedition against Atsïz in 1147 when the latter became rebellious again.[28]

Atsiz was a flexible politician and ruler, and was able to maneuver between the powerful Seljuk Sultan Sanjar and the equally powerful Kara Khitai ruler Yelü Dashi. He continued the land-gathering policy initiated by his predecessors, annexing Jand and Mangyshlak to Khwarazm. Many nomadic tribes were dependent on the Khwarazmshah. Towards the end of his life, Atsiz subordinated the entire northwestern part of Central Asia, and in fact, achieved its independence from its neighbors.[29]

Territorial expansion[edit]

Il-Arslan and Tekish[edit]

Il-Arslan was the Shah of Khwarazm from 1156 until 1172. He was the son of Atsïz. Initially, Il-Arslan was made governor of Jand, an outpost on the Syr Darya which had recently been reconquered, by his father. In 1156, Atsiz died and Il-Arslan succeeded him as Khwarazmshah. Like his father, he decided to pay tribute to both the Seljuk sultan Sanjar and the Qara Khitai gurkhan.

Sanjar died only a few months after Il-Arslan's ascension, causing Seljuq Khurasan to descend into chaos. This allowed Il-Arslan to effectively break off Seljuk suzerainty, although he remained on friendly terms with Sanjar's successor, Mas'ud. Like his father, Il-Arslan sought to expand his influence in Khurasan.

In 1158, Il-Arslan became involved in the affairs of another Qara Khitai vassal state, the Karakhanids of Samarqand. The Karakhanid Chaghri Khan had been persecuting the Qarluks in his realm, and several Qarluk leaders fled to Khwarazm and sought Il-Arslan's help. He responded by invading the Karakhanid dominions, taking Bukhara and besieging Samarqand, where Chaghri Khan had taken refuge. The latter appealed to both the Turks of the Syr Darya and the Qara Khitai, and the gurkhan sent an army, but its commander hesitated to enter into conflict with the Khwarazmians.

In 1172, the Qara Khitai launched a punitive expedition against Il-Arslan, who had not paid the required annual tribute. The Khwarazmian army was defeated, and Il-Arslan died shortly after. Following his death the state briefly became embroiled in turmoil, as the succession was disputed between his sons Tekish and Sultan Shah. Tekish emerged victorious and subsequently ruled the empire from 1172 to 1200.

Tekish stayed with the expansionist policies of his father Il-Arslan. Despite gaining his throne with the help of the Qara Khitai, he later shook off their suzerainty and repulsed the subsequent Qara Khitai invasion of Khwarazm. Tekish maintained close relations with the Oghuz Turkmens and Turkic Qipchak tribes from the vicinity of the Aral Sea, and recruited them at times for his conquest of Iran. A great number of these Turkmens were still pagan, and they were known in Iran for their barbarism and intense ferocity.[31]

In 1194, Tekish defeated the Seljuq sultan of Hamadan, Toghrul III, in an alliance with Caliph Al-Nasir, and conquered his territories. After the war, he broke with the Caliphate and was on the brink of a war with it until the Caliph accepted him as the sultan of Iran, Khorasan, and Turkestan in 1198. Tekish died of a peritonsillar abscess in 1200.[32] and was succeeded by his son, Ala ad-Din Muhammad. His death triggered spontaneous revolts and widespread massacre of the hated Khwarazmian Turkic soldiers stationed in Iran.[33]

Maximum expansion and decline[edit]

Ala al-Din Muhammad[edit]

After his father Tekish died, Muhammad succeeded him. Muhammad led the maximum expansion of the Khwarazmian Empire, extinguishing the Western Kara-Khanid Khanate in 1213, and sweeping aside the Ghurids in 1215 whom they vassalized after the assassination of Muhammad Ghuri. The coins of Muhammad were minted in the Kara-Khanid capitals of Uzgen and Samarkand from 1213.[36]

In 1218, a small contingent of Mongols crossed borders in pursuit of an escaped enemy general. Upon successfully retrieving him, Genghis Khan made contact with the Shah. Genghis was looking to open trade relations, but having heard exaggerated reports of the Mongols, the Shah believed this gesture was only a ploy to invade Khwarazm.

Genghis sent emissaries to Khwarazm to emphasize his hope for a trade road. Muhammad II, in turn, had one of his governors (Inalchuq, his uncle) openly accuse the party of spying, seizing their rich goods and arresting the party.[37]

Trying to maintain diplomacy, Genghis sent an envoy of three men to the shah, to give him a chance to disclaim all knowledge of the governor's actions and hand him over to the Mongols for punishment. The shah executed the envoy (again, some sources claim one man was executed, some claim all three were), and then immediately had the Mongol merchant party (Muslim and Mongol alike) put to death and their goods seized.[38] These events led Genghis to retaliate with a force of 100,000 to 150,000 men that crossed the Jaxartes in 1219 and sacked the cities of Samarqand, Bukhara, Otrar, and others. Muhammad's capital city, Gurganj, followed soon after. The Shah Muhammad II of Khwarazm fled and died some weeks later on an island in the Caspian Sea.

Turkan Khatun[edit]

On the eve of the Mongol invasion, a diarchy developed in the Khwarazmian Empire. Khwarazmshah Muhammad II was considered the absolute ruler, but the influence of his mother Turkan Khatun (Terken Khatun) was also great. Turkan Khatun even had the laqab: "the Ruler of the World" (Khudavand-e Jahaan), and another one for her decrees: "Protector of peace and faith, Turkan the Great, the ruler of women of both worlds." Turkan Khatun had a separate Diwan, separate palace and the orders of the Sultan were not considered to be effective without her signature. This fact, coupled with her conflicts with Muhammad II might have contributed to the impotence of the Khwarazmian Empire in the face of the Mongol onslaught.

In 1221, she was captured by the troops of Genghis Khan and died in poverty in Mongolia.

Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu[edit]

Jalal al-Din was the last of Khwarazmshahs, who ruled the remnants of the Khwarazmian Empire and northwestern India from 1220 to 1231. He was reportedly the eldest son of Ala ad-Din Muhammad II, while his mother was a Turkmen concubine named Ay Chichek.[41] Due to the low status of Jalal al-Din's mother, his powerful grandmother and Qipchaq princess Terken Khatun refused to support him as heir to the throne, and instead favored his half-brother Uzlagh-Shah, whose mother was also a Qipchaq. Jalal al-Din first appears in historical records in 1215, when Muhammad II divided his empire amongst his sons, giving the southwestern part (part of the former Ghurid Empire) to Jalal al-Din.[42]

He attempted to flee to India, but the Mongols caught up with him before he got there, and he was defeated at the Battle of Indus. He escaped and sought asylum in the Sultanate of Delhi. Iltumish however denied this to him in deference to the relationship with the Abbasid caliphs. Returning to Persia, he gathered an army and re-established a kingdom. He never consolidated his power, however, spending the rest of his days struggling against the Mongols, the Seljuks of Rum, and pretenders to his own throne. He lost his power over Persia in a battle against the Mongols in the Alborz Mountains. Escaping to the Caucasus, he captured Azerbaijan in 1225, setting up his capital at Tabriz. In 1226 he attacked Georgia and sacked Tbilisi. Following on through the Armenian highlands he clashed with the Ayyubids, capturing the town Ahlat along the western shores of Lake Van, which sought the aid of the Seljuq Sultanate of Rûm. Sultan Kayqubad I defeated him at Arzinjan on the Upper Euphrates at the Battle of Yassıçemen in 1230. He escaped to Diyarbakir, while the Mongols conquered Azerbaijan in the ensuing confusion. He was murdered in 1231 by Kurdish highwaymen.[43]

State apparatus[edit]

The head of the central state apparatus (al-Majlis al-Ali al-Fahri at-Taji) of Kharazmshahs was a vizier, the first adviser to the head of state. He was the head of the diwan officials (askhab ad-dawawin), who appointed them and established salaries, pensions (arzak), controlling tax administration and the treasury.[44] The most prominent vizier of the Khwarazmian Empire was Al-Harawi, who built a mosque for the Shafi'is in Merv, a huge madrassah, a mosque and a repository of manuscripts in Gurganj. He died at the hands of the Shia Ismailis.[45]

An important position in the state apparatus of the Khwarazmshahs was also held by the senior or great hajib, who most of the time, was a representative of the Turkic nobility. The hajib reported to the Khwarazmshah on issues related to the shah and his family. The Khwarazmshah could have several hajibs, who carried out the "personal" instructions of the sultan.[46]

Capital cities[edit]

Initially, the main city of the Khwarazmian Empire was Urganch or Gurganj. A prominent Middle Eastern biographer and geographer, Yaqut al-Hamawi, who visited Gurganj in 1219, wrote, "I have not seen a city greater, richer and more beautiful than Gurganj." Al-Qazvini, a Persian physician, astronomer, geographer and writer of Arab ancestry, states:

Gurganj is a very beautiful city, surrounded by the attention of angels who represent the city in paradise just like a bride in a groom's house. The inhabitants of the capital were skillful artisans, especially the blacksmiths, carpenters and others. Carvers were famous for their products made of ivory and ebony. Workshops for the production of natural silk operated in the city.[47]

The cities of Samarqand, Ghazna and Tabriz also served as the capital of the later Khwarazmian Empire.

Population[edit]

The population of the Kwarazmian Empire consisted mainly of sedentary Iranian and half-nomadic Turkic peoples.[48]

The urban population of the empire was concentrated in a relatively small number of (by medieval standards) very large cities as opposed to a huge number of smaller towns. The population of the empire is estimated at 5 million people on the eve of the Mongol invasion in 1220, making it sparse for the large area it covered.[8][note 1] Historical demographers Tertius Chandler and Gerald Fox give the following estimations for the populations of the empire's major cities at the beginning of the 13th century, which adds up to at least 520,000 and at most 850,000 people:[52]

- Samarqand: 80,000–100,000

- Nishapur: 70,000

- Rayy/Rey: 100,000

- Isfahan: 80,000

- Merv: 70,000

- Balkh: c. 30,000

- Bost: c. 40,000

- Herat: c. 40,000

- Otrar, Urgench, and Bukhara: unknown, but less than 70,000.[53]

Culture[edit]

Although the Khwarazmshahs had a Turkic origin, just as their Seljuq predecessors, they adopted Persian culture, adhered to the Sunni branch of Islam and had their richest and most populous cities in Khorasan. Thus, the Khwarazmshah era had a dual character, reflecting both its Turkic origin and Persian high culture.

Language[edit]

During the Khwarazmshah era, Central Asian society was fragmented, unified under one banner only recently. The Khwarazmian military mostly consisted of Turks, while the civilian and administrative element was almost exclusively Persian. The spoken language of the Turkic population of Khwarazm was Kipchak Turkic and Oghuz, the latter being the legacy of the previous masters of the area, Seljuq Turkomans.[56]

However, the dominant language of the era and the one spoken by the majority in the important Khwarazmian cities was Persian. The language of the sedentary diwan was also Persian, and its members had to be well versed in Persian culture, regardless of their ethnic origin. Persian became the official state language of the Khwarazmshahs and served as the language of administration, history, fiction and poetry. The Turkic language was the mother tongue and "home language" of the Anushteginid family, while Arabic served primarily as the language of science, philosophy, and theology.

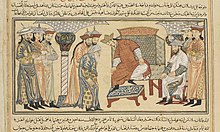

Ceramics in the Khwarazmian period[edit]

The finely decorated Mina'i ceramics were mainly produced in Kashan, in the decades leading up to the Mongol invasion of Persia in 1219, at a time when the Khwarazmian Empire ruled the area, initially under the suzerainty of the Seljuk Empire, and independently from 1190.[57] Some of the "most iconic" productions of stonepaste vessels can be attributed to the Khwarazmian rulers, after the end of Seljuk domination (the Seljuk Empire itself ended in 1194).[58] In general, it is considered that Mina'i ware was manufactured from the late 12th century and the early 13th century, and dated Mina’i wares range from 1186 to 1224.[59] Extensive lusterware also belongs to this period.

-

Horsemen, Mina'i ware, early 13th century, Iran[60]

-

Mina'i Bowl with horserider, early 13th century, Iran[61]

-

Mina'i Lobed bowl, early 13th century, Iran[62]

Military[edit]

It is estimated that the Khwarazmian army, prior to the Mongol invasion, consisted of about 40,000 cavalry, mostly of Turkic origin. Militias existed in Khwarazm's major cities but were of poor quality. With collective populations of around 700,000, the major cities probably had 105,000 to 140,000 healthy males of fighting age in total (15–20% of the population), but only a fraction of these would be part of a formal militia with any notable measure of training and equipment.[64]

Mercenaries[edit]

After the Mongol invasion of the Khwarazmian Empire, many Khwarazmians survived by employing themselves as mercenaries in northern Iraq. Sultan Jalal ad-Din's followers remained loyal to him even after his death in 1231, and raided the Seljuq lands of Jazira and Syria for the next several years, calling themselves the Khwarazmiyya. Ayyubid Sultan as-Salih Ayyub, in Egypt, later hired them against his uncle as-Salih Ismail. The Khwarazmiyya, heading south from Iraq towards Egypt, invaded Crusader-held Jerusalem along the way, on 11 July 1244 (Siege of Jerusalem (1244)). The city's citadel, the Tower of David, surrendered on 23 August, and the Christian population of the city was expelled. This triggered a call from Europe for the Seventh Crusade, but the Crusaders would never again be successful in retaking Jerusalem. After being conquered by the Khwarazmian forces, the city stayed under Muslim control until 1917, when it was taken from the Ottomans by the British.

After taking Jerusalem, the Khwarazmian forces continued south, and on 17 October 1244 fought on the side of the Ayyubids at the Battle of La Forbie, as the Crusaders used to call Harbiyah, a village northeast of Gaza, destroying the remains of the Crusader army there, with some 1,200 knights killed. It was the largest battle involving the Crusaders since the Battle of the Horns of Hattin in 1187.[69]

See also[edit]

| History of the Turkic peoples pre–14th century |

|---|

|

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Additionally, the population of roughly the same area (Persia and Central Asia) plus some others (Caucasia and northeast Anatolia) is estimated at 5–6 million nearly 400 hundreds later, under the rule of the Safavid dynasty.[51]

- ^ Also known as Khwarazm (Persian: خوارزم, romanized: Khwārazm) or the Khwarazmshahs (Persian: خوارزمشاهیان, romanized: Khwārazmshāhiyān)

- ^ Medieval historians such as Hafiz-i Abru and Rashid al-Din believed that Anushtegin was of Begdili tribe of Oghuz Turks,[23][24] while Turkish historian Kafesoğlu states that Anushtegin was either of Khalaj or Chigil origin and the Bashkir historian Zeki Velidi Togan believes he was of Qipchaq, Qanghli or Uyghur descent.[25]

References[edit]

- ^ Babayan 2003, p. 14.

- ^ Katouzian 2007, p. 128.

- ^ Kuznetsov & Fedorov 2013, p. 145.

- ^ Gafurov, B.G. Central Asia:Pre-Historic to Pre-Modern Times, Vol. 2, (Shipra Publications, 1989), p. 359.

- ^ Vasilyeva, G.P. "Ethnic processes in origins of Turkmen people." Soviet Ethnography. Publishing house: Nauka, 1969. pp. 81–98.

- ^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D. (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 497. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793.

- ^ a b John Man, "Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection", February 6, 2007. p. 180.

- ^ "Khwarazmian: definition". Merriam Webster. n.d. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ^ Bosworth, C.E. (1998). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. UNESCO. p. 164. ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1.

Mahm ̄ud and Masc ̄ud I of Ghazna had appointed Turkish slave commanders from their own army, Altuntash and his sons, as governors there with the ancient title of Khwarazm Shah." (...) "In order to secure these important regions, Malik Sh ̄ah had appointed the keeper of the royal washing bowls (tast-d ̄ar), his slave commander An ̄ush-tegin Gharcha' ̄ı, as titular governor at least in Khwarazm. During Berkyaruk's reign, the sultan appointed in 1097 another Turkishghul ̄am, Ekinchi b. Kochkar, with the historic title of KhwarazmShah. When, in that same year, Ekinchi was killed, Berkyaruk nominated in his stead An ̄ushtegin's son Qutb al-D ̄ın Muhammad as governor, and Muhammad's tenure of power there (1097–1127) inaugurates the fourth and most brilliant line of hereditary KhwarazmShahs

- ^ C. E. Bosworth : Khwarazmshahs i. Descendants of the line of Anuštigin. In Encyclopaedia Iranica, online ed., 2009: "Little specific is known about the internal functioning of the Khwarazmian state, but its bureaucracy, directed as it was by Persian officials, must have followed the Saljuq model. This is the impression gained from the various Khwarazmian chancery and financial documents preserved in the collections of enšāʾdocuments and epistles from this period. The authors of at least three of these collections—Rašid-al-Din Vaṭvāṭ (d. 1182–83 or 1187–88), with his two collections of rasāʾel, and Bahāʾ-al-Din Baḡdādi, compiler of the important Ketāb al-tawaṣṣol elā al-tarassol—were heads of the Khwarazmian chancery. The Khwarazmshahs had viziers as their chief executives, on the traditional pattern, and only as the dynasty approached its end did ʿAlāʾ-al-Din Moḥammad in ca. 615/1218 divide up the office amongst six commissioners (wakildārs; see Kafesoğlu, pp. 5–8, 17; Horst, pp. 10–12, 25, and passim). Nor is much specifically known of court life in Gorgānj under the Khwarazmshahs, but they had, like other rulers of their age, their court eulogists, and as well as being a noted stylist, Rašid-al-Din Vaṭvāṭ also had a considerable reputation as a poet in Persian." Norman M. Naimark, Genocide: A World History (Oxford University Press, 2017), 20 "The Persian-speaking and Islamic Khwarezmian empire, which was founded in Central Asia south of the Aral Sea around its capital of Samarkand, and included such remarkable centers of trade and civilizations as Bukhara and Urgench, ..."

- ^ Rene Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes:A History of Central Asia, Transl. Naomi Walford, Rutgers University Press, 1991, p. 159.

- ^ Biran, Michel, The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian history, (Cambridge University Press, 2005), 44.

- ^ Bosworth, C.E. (1998). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. UNESCO. p. 164. ISBN 978-92-3-103467-1.

This dynasty eventually built up, as the Seljuq empire in the east tottered to its close, the most powerful and aggressively expansionist empire in the Persian lands, in the end defeating their rivals for control of Khurasan, the Ghurids of Afghanistan, threatening western Persia and Iraq and the Abbasid caliphate itself, and only disintegrating under the overwhelming military might of the Mongol invaders in the opening decades of the thirteenth century.

- ^ Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ^ Rein Taagepera (September 1997). "Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia". International Studies Quarterly. 41 (3): 497. doi:10.1111/0020-8833.00053. JSTOR 2600793.

- ^ David Abulafia (2015). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 5, c. 1198–c. 1300. p. 610.

- ^ C.E. Bosworth, The Ghaznavids: 994-1040, Edinburgh University Press, 1963, page 237

- ^ Buniyatov, Z. The State of Khwarazmshah-Anushteginids. 1097—1231 М., 1986. pages 41-75.

- ^ Biran, Michel, The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History, Cambridge University Press, 2005, 44.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Khwarezm-Shah-Dynasty", (LINK)

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ Fadlullah, Rashid al-Din (1987). Oghuznameh. Baku: Elm.

Similarly, the most distant ancestor of Sultan Muhammad Khwarazmshah was Nushtekin Gharcha, who was a descendant of the Begdili tribe of the Oghuz family.

- ^ Buniyatov, Z.M (1986). The State of Khwarazmshah-Anushteginids (1097-1231). Nauka. p. 80.

- ^ a b Bosworth 1968.

- ^ Bosworth 1968, p. 93.

- ^ Biran, 44.

- ^ Grousset, Rene, The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, (Rutgers University Press, 2002), 160.

- ^ Historical and Cultural Heritage of Turkmenistan: Encyclopedic Dictionary. ed. by: Gundogdyeva, O. A.; Muradova R. G. Istanbul: UNDP, 2000. pp 1-381. ISBN 975-97256-0-6

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ Bosworth, C.E (1968). The Political and Dynastic History of the Iranian World (A.D. 1000-1217). Vol. V. Cambridge. pp. 181–197.

- ^ Juvaini, Ala-ad-Din Ata-Malik, History of the World Conqueror, Manchester University Press, Manchester, 1997. p. 314.

- ^ Kafesoglu, Ibrahim (1956). The History of the State of Khwarazmshah (485-617/1092-1229) (in Turkish). Ankara: Turk Tarih Kurumu. pp. 83–146.

- ^ Keresztély, Kata (14 December 2018). Fiction Painting : a Medieval Arabic Tradition. p. 351.

- ^ The Glory of Byzantium: Art and Culture of the Middle Byzantine Era, A.D. 843-1261. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1997. pp. 428–429. ISBN 978-0-87099-777-8.

- ^ Gafurov, Bobodzhan Gafurovich (2005). Central Asia: Pre-historic to Pre-modern Times. Shipra Publications. ISBN 978-81-7541-245-3.

In Uzgend , the capital of the largest principality of the Karakhanids and in Samarkand , the capital of the Karakhanid state were minted coins in 1213 with the name of Mohammad, Khwarezm Shah . This confirmed the complete annihilation of the dynasty of the Kharakanids

- ^ Svat Soucek (2002). A History of Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 106. ISBN 0-521-65704-0.

- ^ Man, John (2005). Genghis Khan: Life, Death and Resurrection. Bantam. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-553-81498-9.

- ^ "Gebetsnische (Baukeramik) - Recherche | Staatliche Museen zu Berlin". recherche.smb.museum.

- ^ Bast, Oliver (11 August 2020). "GERMANY, Plate IV". Encyclopaedia Iranica Online. Brill.

- ^ Gundogdiyev, O. Historical and Cultural Heritage of Turkmenistan: Encyclopedic Dictionary. Istanbul. 2000. page 381. ISBN 9789759725600

- ^ Paul, Jürgen (2018). "Jalāl al-Dīn Mangburnī". Encyclopedia of Islam - 3. p. 142.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Buniyatov, Z.M. (1999). Selected works in three volumes. Vol. 3. Baku. p. 60.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Buniyatov 1999, p. 61.

- ^ Buniyatov 1999, p. 62.

- ^ Buniyatov 1999, p. 65.

- ^ Gafurov, B.G. Central Asia: Pre-Historic to Pre-Modern Times. vol. 2. Shipra Publications, 1989. p. 359.

- ^ Hillenbrand, Robert (1 January 2010). "The Schefer Ḥarīrī: A Study in Islamic Frontispiece Design". Arab Painting: 118, note 10. doi:10.1163/9789004236615_011. ISBN 978-90-04-23661-5.

- ^ Contadini, Anna (2012). A world of beasts: a thirteenth-century illustrated Arabic book on animals (the Kitāb Na't al-Ḥayawān) in the Ibn Bakhtīshū' tradition. Leiden Boston: Brill. p. 127. ISBN 978-90-04-20100-2.

P.126: "Official" Turkish figures wear a standard combination of a sharbūsh, a three-quarters length robe, and boots. Arab figures, in contrast, have different headgear (usually a turban), a robe that is either full-length or, if three-quarters length, has baggy trousers below, and they usually wear flat shoes or (...) go barefoot (...) P.127: Reference has already been made to the combination of boots and sharbūsh as markers of official status (...) the combination is standard, even being reflected in thirteenth-century Coptic paintings, and serves to distinguish, in Grabar's formulation, the world of the Turkish ruler and that of the Arab. (...) The type worn by the official figures in the 1237 Maqāmāt, depicted, for example, on fol. 59r,67 consists of a gold cap surmounted by a little round top and with fur trimming creating a triangular area at the front which either shows the gold cap or is a separate plaque. A particular imposing example in this manuscript is the massive sharbūsh with much more fur than usual that is worn by the princely official on the right frontispiece on fol. 1v.

- ^ Dale, Stephen Frederic (2002). Indian Merchants and Eurasian Trade, 1600–1750. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0521525978. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ Tertius Chandler & Gerald Fox, "3000 Years of Urban Growth", pp. 232–236.

- ^ Chandler & Fox, p. 232: Merv, Samarkand, and Nipashur are referred to as "vying for the [title of] largest" among the "Cities of Persia and Turkestan in 1200", implying populations of less than 70,000 for the other cities (Otrar and others do not have precise estimates given). "Turkestan" seems to refer to Central Asian Turkic countries in general in this passage, as Samarkand, Merv, and Nishapur are located in modern Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, and northeastern Iran respectively.

- ^ Blair, Sheila S. (2008). "A Brief Biography Of Abu Zayd". Muqarnas, Volume 25. Brill. p. 158. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004173279.i-396.37. ISBN 978-9004173279.

- ^ Hillenbrand, Robert (1999). Islamic art and architecture. London : Thames and Hudson. p. 97, Fig. 70. ISBN 978-0-500-20305-7.

- ^ Vasilyeva, G.P (1969). Ethnic processes in origins of Turkmen people; Soviet Ethnography (in Russian). Nauka (Science). pp. 81–98.

- ^ Komaroff, 4; Michelsen and Olafsdotter, 76; Fitzwilliam Museum: "Mina’i, meaning ‘enamelled’ ware, is one of the glories of Islamic ceramics, and was a speciality of the renowned ceramics centre of Kashan in Iran during the decades of the late 12th and early 13th centuries preceding the Mongol invasions".

- ^ "While stonepaste vessels are often attributed to the Seljuq period, some of the most iconic productions in the medium took place after this dynasty lost control over its eastern territories to other Central Asian Turkic groups, such as the Khwarezm-Shahis" in Rugiadi, Martina. "Ceramic Technology in the Seljuq Period: Stonepaste in Syria and Iran in the Twelfth and Early Thirteenth Centuries". www.metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art (2021). Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- ^ The Grove Encyclopedia of Decorative Arts: Mina'i ware. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2006. ISBN 978-0195189483.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". www.metmuseum.org.

- ^ Sverdrup, Carl. The Mongol Conquests: The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sube'etei. Helion and Company, 2017. pp. 148–150

- ^ Holod, Renata (1 January 2012). "The Freer Gallery's Siege Scene Plate". Ars Orientalis.

- ^ "Bowl". Smithsonian's National Museum of Asian Art.

- ^ Nicolle, David (1997). Men-at-arms series 171 - Saladin and the saracens (PDF). Osprey publishing. p. 36.

- ^ Eastmond, Antony (20 April 2017). Tamta's World. Cambridge University Press. p. 335. ISBN 978-1-107-16756-8.

It has recently been proposed that the dish represents an attack on an Assassin stronghold in eastern Azerbaijan by Jalal al-Din Khwarazmshah in about 1225.

- ^ Riley-Smith The Crusades, p. 191

Sources[edit]

- Babayan, K. (2003). Mystics, monarchs, and messiahs: cultural landscapes of early modern Iran. Harvard Center for Middle Eastern Studies.

- Katouzian, Homa (2007). Iranian History and Politics: The Dialectic of State and Society. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415297547.

- Kuznetsov, Andrew; Fedorov, Michael (2013). "Late Drachms of the Khwārazmshāh Azkājvār and Imitations of such Drachms". Iran: Journal of the British Institute of Persian Studies. 51 (1). Taylor & Francis: 145–149.

External links[edit]

Media related to Khwarazmian Empire at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Khwarazmian Empire at Wikimedia Commons