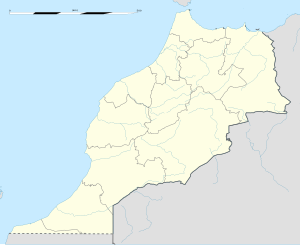

List of World Heritage Sites in Morocco

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Sites are places of importance to cultural or natural heritage as described in the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, established in 1972.[1] Cultural heritage consists of monuments (such as architectural works, monumental sculptures, or inscriptions), groups of buildings, and sites (including archaeological sites). Natural features (consisting of physical and biological formations), geological and physiographical formations (including habitats of threatened species of animals and plants), and natural sites which are important from the point of view of science, conservation, or natural beauty, are defined as natural heritage.[2] The Kingdom of Morocco accepted the convention on 28 October 1975, making its historical sites eligible for inclusion on the list. There are nine World Heritage Sites in Morocco, all selected for their cultural significance.[3]

Morocco's first site, Medina of Fez, was inscribed on the list at the 5th Session of the World Heritage Committee, held in Paris, France in 1981.[4] The most recent inscription, Rabat, Modern Capital and Historic City: a Shared Heritage, was added to the list in 2012.[5] In addition, Morocco maintains a further 13 properties on the tentative list. Morocco has served on the World Heritage Committee twice.[3]

World Heritage Sites[edit]

UNESCO lists sites under ten criteria; each entry must meet at least one of the criteria. Criteria i through vi are cultural, and vii through x are natural.[6]

| Site | Image | Location (region) | Year listed | UNESCO data | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medina of Fez |

|

Fès-Meknès | 1981 | 170; ii, v (cultural) | Fez was founded in the 9th century and reached its apogee as the capital of the Marinid Sultanate in the 13th and 14th centuries and it remained the capital of the country until 1912. The medina is one of the most extensive and best preserved old towns in the Muslim world. The main monuments date to the Medieval period and include mosques, madrasas, palaces, and fountains.[7] |

| Medina of Marrakesh |

|

Marrakesh–Safi | 1985 | 331; i, ii, iv, v (cultural) | Marrakesh was founded in the 1070s as the capital of the Almoravid and later Almohad dynasty until the 13th century when the capital was moved to Fez. There are numerous monuments in the city including the Koutoubia Mosque (pictured), Jemaa el-Fnaa square, El Badi Palace, Bahia Palace, Saadian Tombs, several mosques, and madrasas. The medina remains a living town, preserving its traditional architecture, crafts, and trades.[8] |

| Ksar of Ait-Ben-Haddou |

|

Drâa-Tafilalet | 1987 | 444; iv, v (cultural) | Ait-Ben-Haddou is a ksar, a fortified village, a representative example of a settlement in southern Morocco. It was located on a trans-Saharan trade route. Earthen buildings are packed close together and defensive walls are fortified by towers at the corners. Some of the houses are decorated with motifs in clay brick. The earliest buildings of Ait-Ben-Haddou date from the 17th century although the construction techniques were already present in earlier periods in the region.[9] |

| Historic City of Meknes |

|

Fès-Meknès | 1996 | 793; iv (cultural) | Meknes was founded in the 11th century by the Almoravids. In the 17th century, Sultan Moulay Isma'il ibn Sharif of the Alawi dynasty made it his capital and commissioned substantial construction projects, including monumental defensive walls and ramparts and the Kasbah of Moulay Ismail. The city layout incorporates both Islamic and European aspects of architecture and town planning. Bab Mansur al-'Alj is pictured.[10] |

| Archaeological site of Volubilis |

|

Fès-Meknès | 1997 | 836bis; ii, iii, iv, vi (cultural) | Volubilis was founded in the 3rd century BCE as the capital of Mauretania. It was then an important Roman outpost and in the 8th century briefly the capital of the Idrisid dynasty. Afterwards, the site was not occupied for nearly a thousand years. This resulted in archaeological remains having been well preserved, making Volubilis one of the richest sites in North Africa. The remains demonstrate the interactions of different cultures of the Mediterranean through centuries. A mosaic from the Roman period is pictured. A minor boundary modification took place in 2008.[11] |

| Medina of Tétouan (formerly known as Titawin) |

|

Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima | 1997 | 837; ii, iv, v (cultural) | Located south of the Strait of Gibraltar, Tétouan served as the connection point between Morocco and Andalusia from the 8th century onward. Following the Reconquista, it was rebuilt by refugees expelled by the Spanish and the Andalusian influence is clearly visible in arts and architecture. In the following centuries, it served as the meeting point between Morocco and Spain. The medina quarter is among the smallest in Morocco but it is well preserved.[12] |

| Medina of Essaouira (formerly Mogador) |

|

Marrakesh-Safi | 2001 | 753rev; ii, iv (cultural) | Essaouira was founded by the Alawi Sultan Mohammed ben Abdallah in the second half of the 18th century, with the aim of establishing a major port and trading centre. The city was designed by French architects who followed the principles of French military engineer Marquis of Vauban. In the late 18th and 19th centuries, Essaouira was one of the major Atlantic trading centres between Africa and Europe. Today, the city mainly preserves its European appearance.[13] |

| Portuguese City of Mazagan (El Jadida) |

|

Casablanca-Settat | 2004 | 1058rev; ii, iv (cultural) | In the early 16th century, the Portuguese built a fortified colony of Mazagão as one of the stops on the route to India. They kept it until 1769. The city fortifications followed the principles of Renaissance military engineering, with a star fort plan. Inside the walls, several historic buildings have been preserved, including the Manueline Church of the Assumption and the cistern.[14] |

| Rabat, Modern Capital and Historic City: a Shared Heritage |

|

Rabat-Salé-Kénitra | 2012 | 1401; ii, iv (cultural) | Rabat was rebuilt as the capital of the French protectorate from 1912 to the 1930s. The city is a good example of early 20th century urban planning and is one of the biggest and most ambitious urban projects of the period in Africa. The modern city integrates the buildings from the earlier periods, including the 12th century Kasbah of the Udayas (walls pictured), Hassan Tower, and the Almohad walls and ramparts.[15] |

Tentative list[edit]

In addition to sites inscribed on the World Heritage List, member states can maintain a list of tentative sites that they may consider for nomination. Nominations for the World Heritage List are only accepted if the site was previously listed on the tentative list.[16] Morocco lists 13 properties on its tentative list.[3]

| Site | Image | Location (region) | Year listed | UNESCO criteria | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moulay Idriss Zerhoun |

|

Fès-Meknès | 1995 | ii, iv, vi (cultural) | The town was founded on the slopes of Zerhoun mountain in the 8th century by Idris I, the first major Muslim ruler of Morocco. There are numerous religious monuments in the town, including the mausoleum complex of Idris I (pictured).[17] |

| Taza and the Great Mosque |

|

Fès-Meknès | 1995 | ii (cultural) | Strategically located on the crossroads between the east and west of the country, Taza rose to prominence in the 12th century during the Almohad period when several defensive structures, including walls and bastions, were build. The Great Mosque also dates to that period. It houses a great chandelier (pictured).[18] |

| Tinmal Mosque |

|

Marrakesh–Safi | 1995 | ii, v (cultural) | The mosque, located in the village of Tinmel in the High Atlas, was built to commemorate Ibn Tumart, the founder of the Almohad dynasty.[19] |

| The city of Lixus |

|

Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima | 1995 | ii, iii, iv (cultural) | According to ancient authors, Lixus was one of the first cities in the western Mediterranean. It was occupied from the 8th century BCE to 14th century CE. There are five major stratigraphic phases, Phoenician, Punic, Mauretanian, Roman, and Islamic. The complex includes the remains of several pre-Roman and Roman temples and a large complex to produce salted meat.[20] |

| El Gour |

|

Fès-Meknès | 1995 | iii (cultural) | El Gour is a tumulus, or a burial mound, built in the 4th century BCE for an important person. It is constructed from cut stone blocks arranged in a form of circular steps.[21] |

| Taforalt Cave |

|

Oriental | 1995 | v (cultural) | Taforalt Cave is an important archaeological site from the Paleolithic period. Excavations have uncovered artifacts form the Iberomaurusian lithic industry, as well as a necropolis with about one hundred individuals from the Mechta-Afalou people, dating back around 20,000 years.[22] |

| Talassemtane National Park |

|

Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima | 1998 | vii, x (natural) | The national park, located close to Chefchaouen, features limestone formations such as mountain peaks, gorges, caves, and cliffs. It is home to the endemic Moroccan fir.[23] |

| The area of the dragon tree ajgal |

|

Souss-Massa | 1998 | vii, viii, ix, x (natural) | The area features a pre-steppe ecosystem and is home to endemic plant species, including Dracaena draco ajgal, also known as the dragon tree (pictured), and the argan tree.[24] |

| Khnifiss Lagoon |

|

Guelmim-Oued Noun | 1998 | vii, x (natural) | The lagoon, covering 60,000 ha (150,000 acres), offers different habitats in an otherwise austere desert environment. Prehistoric archaeological remains have been found in the area.[25] |

| Dakhla National Park | Dakhla-Oued Ed-Dahab | 1998 | x (natural) | The area is rich numerous animal and plant species that live in arid climates. The coast is home to a population of monk seals.[26] The park is located in the disputed territory of Western Sahara.[27] | |

| Figuig Oasis |

|

Oriental | 2011 | iii, iv, v (cultural) | The oasis in the Ksour Range close to the border with Algeria is characterized by traditional earthen architecture. Water sources support growing of date palms, there are numerous gardens, irrigation channels, and ponds that create a micro climate different than in the surrounding desert.[28] |

| Casablanca, a twentieth-century city, crossroads of influences |

|

Casablanca-Settat | 2013 | ii, iv (cultural) | The centre of Casablanca was entirely built in the 20th century. The architecture reflects the ideas and influences of different architectural styles from North Africa, Europe, and the United States, including Neo-Moorish, Neoclassical, and Art Deco.[29] |

| String of oases at Tighmert, pre-Saharan region of Wad Noun | Guelmim-Oued Noun | 2016 | iii, iv, v (cultural) | The string of oases is located along the Wad Noun in the length of 30 km (19 mi). They support fortified villages, or ksars and palm groves. Due to the location on trans-Saharan trade routes, the oases are centres of annual and weekly markets. There are numerous archaeological remains in the area.[30] |

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "The World Heritage Convention". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ a b c "Morocco". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 21 November 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ "Report of the 5th Session of the Committee". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ^ "Decision: 36 COM 8B.18". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 23 August 2016. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ^ "UNESCO World Heritage Centre – The Criteria for Selection". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 12 June 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "Medina of Fez". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 19 September 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ "Medina of Marrakesh". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ "Ksar of Ait-Ben-Haddou". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ "Historic City of Meknes". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 7 September 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ "Archaeological Site of Volubilis". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 13 September 2023. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ "Medina of Tétouan (formerly known as Titawin)". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 1 August 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ "Medina of Essaouira (formerly Mogador)". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ "Portuguese City of Mazagan (El Jadida)". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 3 August 2022. Retrieved 17 August 2011.

- ^ "Rabat, Modern Capital and Historic City: a Shared Heritage". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 23 August 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ "Tentative Lists". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Moulay Idriss Zerhoun" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 8 August 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Taza et la Grande Mosquée" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 10 May 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Mosquée de Tinmel" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 1 October 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Ville de Lixus" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 14 May 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "El Gour" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 1 July 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Grotte de Taforalt" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Parc naturel de Talassemtane" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Aire du Dragonnier Ajgal" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Lagune de Khnifiss" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 5 February 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Lagune de Khnifiss" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 5 February 2023. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "A/RES/35/19 - E - A/RES/35/19". Question of Western Sahara. p. 214. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 8 Apr 2021.

- ^ "Oasis de Figuig" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Casablanca, Ville du XXème siècle, carrefour d'influences" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ "Le chapelet d'oasis de Tighmert, Région présaharienne du Wad Noun" (in French). UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2023.