List of modern great powers

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2023) |

A great power is a nation, state or empire that, through its economic, political and military strength, is able to exert power and influence not only over its own region of the world, but beyond to others.

In a modern context, recognized great powers first arose in Europe during the post-Napoleonic era.[1] The formalization of the division between small powers[2] and great powers came about with the signing of the Treaty of Chaumont in 1814.

The historical terms "Great Nation", a distinguished aggregate of people inhabiting a particular country or territory, and "Great Empire",[3] a considerable group of states or countries under a single supreme authority, are colloquial; their use is seen in ordinary historical conversations.[4][5][6]

Early modern powers[edit]

France (1534–1792, 1792–1804, 1804–1815)[edit]

France was a dominant empire possessing many colonies in various locations around the world. Still participating in his deadly Italian conflicts, Francis I of France managed to finance expeditions to find trade routes to China or Cathay through landmass already discovered by the Spanish under Giovanni da Verrazzano. Giovanni would lead the first French discovery of the "New World" just north of the Spanish invasions of Mesoamerica later as New Spain and a decade later Jacques Cartier would firmly colonize the landmass in the name of Francis I. This New World colony would become New France, the first colony of the Kingdom of France. During the reign of Louis XIV, Sun King, from 1643 to 1715, France was the leading European power as Europe's most populous, richest and powerful country. The Empire of the French (1804–1814), also known as the Greater French Empire or First French Empire, but more commonly known as the Napoleonic Empire, was also the dominant power of much of continental Europe and, it ruled over 90 million people and was the sole power in Europe if not the world as Britain was the only main rival during the early 19th century. From the 16th to the 17th centuries, the first French colonial empire stretched from a total area at its peak in 1680 to over 10 million km2 (3.9 million sq mi), the second largest empire in the world at the time behind only the Spanish Empire. It had many possessions around the world, mainly in the Americas, Asia and Africa. At its peak in 1750, French India had an area of 1.5 million km2 (0.58 million sq mi) and a totaled population of 100 million people and was the most populous colony under French rule.[7]

Napoleon became Emperor of the French (French: L'Empereur des Français) on 18 May 1804 and crowned Emperor 2 December 1804, ending the period of the French Consulate, and won early military victories in the War of the Third Coalition against Austria, Prussia, Russia, Portugal, and allied nations, notably at the Battle of Austerlitz (1805) and the Battle of Friedland (1807). The Treaty of Tilsit in July 1807 ended two years of bloodshed on the European continent. Subsequent years of military victories known collectively as the Napoleonic Wars extended French influence over much of Western Europe and into Poland. At its height in 1812, the French Empire had 130 départements, ruled over 90 million subjects, maintained extensive military presence in Germany, Italy, Spain, and the Duchy of Warsaw, and could count Prussia, Russia and Austria as nominal allies.[8]

Early French victories exported many ideological features of the French Revolution throughout Europe. Napoleon gained support by appealing to some common concerns of the people. In France, these included fear by some of a restoration of the ancien régime, a dislike of the Bourbons and the emigrant nobility who had escaped the country, a suspicion of foreign kings who had tried to reverse the Revolution – and a wish by Jacobins to extend France's revolutionary ideals.

The feudal system was abolished, aristocratic privileges were eliminated in all places except Poland, and the introduction of the Napoleonic Code throughout the continent increased legal equality, established jury systems, and legalized divorce. Napoleon placed relatives on the thrones of several European countries and granted many titles, most of which expired with the fall of the Empire. Napoleon wished to make an alliance with South India Mysore ruler Tipu Sultan and provide them French-trained army during the Anglo-Mysore Wars, with the continuous aim of having an eventual open way to attack the British in India.[9][10]

Historians have estimated the death toll from the Napoleonic Wars to be 6.5 million people, or 15% of the French Empire's subjects. The War of the Sixth Coalition, a coalition of Austria, Prussia, Russia, the United Kingdom, Sweden, Spain and a number of German States finally defeated France and drove Napoleon Bonaparte into exile on Elba. After Napoleon's disastrous invasion of Russia, the continental powers joined Russia, Britain, Portugal and the rebels in Spain. With their armies reorganized, they drove Napoleon out of Germany in 1813 and invaded France in 1814, forcing Napoleon to abdicate and thus leading to the restoration of Bourbon rule.

Spanish Empire (1492–1815)[edit]

In the 16th century Spain and Portugal were in the vanguard of European global exploration and colonial expansion and the opening of trade routes across the oceans, with trade flourishing across the Atlantic Ocean between Spain and the Americas and across the Pacific Ocean between Asia-Pacific and Mexico via the Philippines. Conquistadors toppled the Aztec, Inca, and Maya civilizations, and laid claim to vast stretches of land in North and South America. For a long time, the Spanish Empire dominated the oceans with its navy and ruled the European battlefield with its infantry, the famous tercios. Spain enjoyed a cultural golden age in the 16th and 17th centuries as Europe's foremost power.

From 1580 to 1640 the Spanish Empire and the Portuguese Empire were conjoined in a personal union of its Habsburg monarchs, during the period of the Iberian Union, though the empires continued to be administered separately.

From the middle of the 16th century silver and gold from the American mines increasingly financed the military capability of Habsburg Spain, then the foremost global power, in its long series of European and North African wars. Until the loss of its American colonies in the 19th century, Spain maintained one of the largest empires in the world, even though it suffered fluctuating military and economic fortunes from the 1640s. Confronted by the new experiences, difficulties and suffering created by empire-building, Spanish thinkers formulated some of the first modern thoughts on natural law, sovereignty, international law, war, and economics – they even questioned the legitimacy of imperialism – in related schools of thought referred to collectively as the School of Salamanca.

Constant contention with rival powers caused territorial, commercial, and religious conflict that contributed to the slow decline of Spanish power from the mid-17th century. In the Mediterranean, Spain warred constantly with the Ottoman Empire; on the European continent, France became comparably strong. Overseas, Spain was initially rivaled by Portugal, and later by the English and Dutch. In addition, English-, French-, and Dutch-sponsored privateering and piracy, overextension of Spanish military commitments in its territories, increasing government corruption, and economic stagnation caused by military expenditures ultimately contributed to the empire's weakening.

Spain's European empire was finally undone by the Peace of Utrecht (1713), which stripped Spain of its remaining territories in Italy and the Low Countries. Spain's fortunes improved thereafter, but it remained a second-rate power in Continental European politics. However, Spain maintained and enlarged its vast overseas empire until the 19th century, when the shock of the Peninsular War sparked declarations of independence in Quito (1809), Venezuela and Paraguay (1811) and successive revolutions that split away its territories on the mainland (the Spanish Main) of the Americas.

Tsardom of Russia and Russian Empire (1547–1917)[edit]

The Russian Empire formed from what was Tsardom of Russia under Peter the Great. Emperor Peter I (1682–1725) fought numerous wars and expanded an already vast empire into a major European power. He moved the capital from Moscow to the new model city of Saint Petersburg, which was largely built according to Western design. He led a cultural revolution that replaced some of the traditionalist and medieval social and political mores with a modern, scientific, Western-oriented, and rationalist system. Empress Catherine the Great (1762–1796) presided over a golden age; she expanded the state by conquest, colonization, and diplomacy, while continuing Peter I's policy of modernization along Western European lines. Emperor Alexander I (1801–1825) played a major role in defeating Napoleon's ambitions to control Europe, as well as constituting the Holy Alliance of conservative monarchies. Russia further expanded to the west, south and east, becoming one of the most powerful European empires of the time. Its victories in the Russo-Turkish Wars were checked by defeat in the Crimean War (1853–1856), which led to a period of reform and intensified expansion in Central Asia.[11] Following these conquests, Russia's territories spanned across Eurasia, with its western borders ending in eastern Poland, and its eastern borders ending in Alaska. By the end of the 19th century the area of the empire was about 22,400,000 square kilometers (8,600,000 sq mi), or almost 1⁄6 of the Earth's landmass; its only rival in size at the time was the British Empire. The majority of the population lived in European Russia. More than 100 different ethnic groups lived in the Russian Empire, with ethnic Russians composing about 45% of the population.[12] Emperor Alexander II (1855–1881) initiated numerous reforms, most dramatically the emancipation of all 23 million serfs in 1861.

Qing dynasty (China) (1644–1912)[edit]

The Qing dynasty was the last ruling dynasty of China, proclaimed in 1636 and collapsed in 1912 (with a brief, abortive restoration in 1917). It was preceded by the Ming dynasty and followed by the Republic of China. The dynasty was founded by the Manchu clan Aisin Gioro in what is today Northeast China (also known as "Manchuria"). Starting in 1644, it expanded into China proper and its surrounding territories. Complete pacification of China proper was accomplished around 1683 under the Kangxi Emperor. The multiethnic Qing Empire assembled the territorial base for modern China. It was the largest Chinese dynasty and in 1790 the fourth largest empire in world history in terms of territorial size. With a population of 432 million in 1912, it was the world's most populous country at the time. The Qing dynasty also reached its economic peak in 1820, when it became the world's largest economy, and contributing to 30% of world GDP.[13]

Originally the Later Jin dynasty, the dynasty changed its official name to "Great Qing", meaning "clear" or "pellucid", in 1636. In 1644, Beijing was sacked by a coalition of rebel forces led by Li Zicheng, a minor Ming official who later proclaimed the Shun dynasty. The last Ming emperor, the Chongzhen Emperor, committed suicide when the city fell, marking the official end of the Ming dynasty. Qing forces then allied with Ming general Wu Sangui and seized control of Beijing and expel Shun forces from the city.[14]

The Qing dynasty reached its height in the ages of the Kangxi Emperor, Yongzheng Emperor and the Qianlong Emperor. The Ten Great Campaigns and in addition, the conquest of the western territories of the Mongols, Tibetans, and Muslims under the rule of the Qing were another factor of prosperity. Again, the skillful rule of the era's emperors allowed for this success. Rule through chiefdoms in territories like Taiwan, allowed for the conquered peoples to retain their culture and be ruled by their own people while the Qing Empire still possessed the ultimate control and rule. These such ruling tactics created for little need or reason for rebellion of the conquered.[15] Another aspect of Manchu rule under the Qing Empire was rule within modern day China. The Mongols' attempt to rule may have failed because they attempted to rule from the outside. The High Qing emperors ruled from within, enabling them to obtain and retain stable and efficient control of the state.

A new generation of emperors that combined the strengths of their culture in addition to a level of sinicization of the conquered cultures in order to combine assimilation and the retaining of their own cultural identity. This was initiated with the Kangxi Emperor who was in power at the initiation of the High Qing. As an emperor he elevated the status of the Qing Empire through his passion for education in combination with his military expertise, and his restructuring of the bureaucracy into that of a cosmopolitan one. His son and successor, the Yongzheng Emperor ruled differently through more harsh and brutal tactics, but was also an efficient and unprecedented level of commitment to the betterment of the empire.[16] The last successful emperor of the High Qing was the Qianlong Emperor who, following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, was a well-rounded ruler who created the peak of the High Qing Empire. The unique and unprecedented ruling techniques of these three emperors, and the emphasis on multiculturalism[17] fostered the productivity and success that is the High Qing era.

A heavy revival of the arts was another characteristic of the High Qing Empire. Through commercialization, items such as porcelain were mass-produced and used in trade. Also, literature was emphasized as Imperial libraries were erected, and literacy rates of men and women both, rose within the elite class. The significance of education and art in this era is that it created for economic stimulation that would last for a period of over fifty years.[18] After his death, the dynasty faced changes in the world system, foreign instrusion, internal revolts, population growth, economic disruption, official corruption, and the reluctance of Confucian elites to change their mindsets. With peace and prosperity, the population rose to some 400 million, but taxes and government revenues were fixed at a low rate, soon leading to a fiscal crisis.

First British Empire (1600–1783)[edit]

At the end of the 16th century, England and the Dutch Empire began to challenge the Portuguese Empire's monopoly of trade with Asia, forming private joint-stock companies to finance the voyages—the English, later British, East India Company and the Dutch East India Company, chartered in 1600 and 1602 respectively. The primary aim of these companies was to tap into the lucrative spice trade, an effort focused mainly on two regions: the East Indies archipelago, and an important hub in the trade network, India. There, they competed for trade supremacy with Portugal and with each other.[19] Although England eclipsed the Netherlands as a colonial power, in the short term the Netherlands' more advanced financial system[20] and the three Anglo-Dutch Wars of the 17th century left it with a stronger position in Asia. Hostilities ceased after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 when the Dutch William of Orange invaded and ascended the English throne, bringing peace between the Dutch Republic and England. A deal between the two nations left the spice trade of the East Indies archipelago to the Netherlands and trade with the textiles industry of India to England, but textiles soon overtook spices in terms of profitability.[20]

During the 17th and 18th centuries, British colonies were created along the east coast of North America. The southern colonies had a plantation economy, made possible by enslavement of Africans, which produced tobacco and cotton. This cotton was especially important in the development of British textile towns and the rise of the world's first Industrial Revolution in Britain by the end of this period. The northern colonies provided timber, ships, furs, and whale oil for lamps; allowing work to be done at times of the day without natural light.[21][22] All of these colonies served as important captive markets for British finished goods and trade goods including British textiles, Indian tea, West Indian coffee, and other items.[23]

The First British Empire participated in the Seven Years' War officially from 1756, a war described by some historians as the world's first World War.[24] The British had hoped winning the war against its colonial rival France would improve the defensibility of its important American colonies, where tensions from settlers eager to move west of the Appalachian Mountains had been a substantive issue.[25] The new British-Prussian alliance was successful in forcing France to cede Canada to Britain, and Louisiana to Spain, thus ostensibly securing British North America from external threats as intended. The war also allowed Britain to capture the proto-industrialised Bengal from the French-allied Mughal Empire, then Britain's largest competitor (and by far the world's single largest producer) in the textile trade, it was also able to flip Hyderabad from the Mughals to its cause, and capture the bulk of French territorial possessions in India, effectively shutting them out of the sub-continent.[26][27] Importantly, the war also saw Britain becoming the dominant global naval power.[28]

Regardless of its successes in the Seven Years' War, the British government was left close to bankruptcy and in response it raised taxes considerably in order to pay its debts.[29] Britain was also faced with the delicate task of pacifying its new French-Canadian subjects, as well as the many American Indian tribes who had supported France, without provoking a new war with France. In 1763, Pontiac's War broke out as a group of Indian tribes in the Great Lakes region and the Northwest (the modern American Midwest) were unhappy with the loss of congenial and friendly relations with the French and complained about being cheated by the new British monopoly on trade.[30] Moreover, the Indians feared that British rule would lead to white settlers displacing them from their land, whereas it was known that the French had only come as fur traders, and indeed this had been the original source of animosity on the part of British settlers with France and part of the reason the war had started in the first place.[30] Pontiac's War was going very badly for the British and it was only with their victory at the Battle of Bushy Run that a complete collapse of British power in the Great Lakes region was avoided.[31]

In response King George III issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which forbade white settlement beyond the crest of the Appalachians, with the hope of appeasing the Indians and preventing further insurrection, but this led to considerable outrage in the Thirteen Colonies, whose inhabitants were eager to acquire native lands. The Quebec Act of 1774, similarly intended to win over the loyalty of French Canadians, also spurred resentment among American colonists.[32] As such, dissatisfaction with the Royal Proclamation and "Taxation Without Representation" are said to have led to the Thirteen Colonies declaring their independence and starting the American War of Independence (1775–1783).[33][29]

This war was comprehensively supported by Britain's competitors, France and Spain, and Britain lost the war marking the end of the first British Empire. Britain and the new United States of America were able to retain the pre-existing trade arrangements from before independence, minimizing long-term harm to British trading interests. After the war of independence the American trade deficit with Britain was approximately 5:1 causing a shortage of gold for a number of years.[34] However, the British Empire would shift its focus from North America to India, expanding from its new base in Bengal and signalling the beginning of the second phase of the British Empire.

Portugal (1415–1822)[edit]

The Portuguese Empire[35] was the first global empire in history, and also the earliest and longest-lived of the Western European colonial empires. Portugal's small size and population restricted the empire, in the 16th century, to a collection of small but well defended outposts along the African coasts, the main exceptions being Angola, Mozambique and Brazil. For most of the 16th century, the Portuguese Indian Armadas, then the world leader navy in shipbuilding and naval artillery, dominated most of the Atlantic Ocean south of the Canary Islands, the Indian Ocean and the access to the western Pacific. The height of the empire was reached in the 16th century but the indifference of the Habsburg kings and the competition with new colonial empires like the British, French and Dutch started its long and gradual decline. After the 18th century Portugal concentrated in the colonization of Brazil and African possessions.

The Treaty of Tordesillas, between Spain and Portugal, divided the world outside of Europe in an exclusive duopoly along a north–south meridian 370 leagues, or 970 miles (1,560 km), west of the Cape Verde islands. However, as it was not possible at the time to correctly measure longitude, the exact boundary was disputed by the two countries until 1777. The completion of these negotiations with Spain is one of several reasons proposed by historians for why it took nine years for the Portuguese to follow up on Dias's voyage to the Cape of Good Hope, though it has also been speculated that other voyages were in fact secretly taking place during that time. Whether or not this was the case, the long-standing Portuguese goal of finding a sea route to Asia was finally achieved in a ground-breaking voyage commanded by Vasco da Gama.

Dutch Empire (1581–1795)[edit]

The Dutch Empire controlled various territories after the Dutch achieved independence from Spain in the 16th century. The strength of their shipping industry and the expansion of trading routes between Europe and the Orient bolstered the strength of the overseas colonial empire which lasted from the 16th to the 20th century. The Dutch initially built up colonial possessions on the basis of indirect state capitalist corporate colonialism, as small European trading-companies often lacked the capital or the manpower for large-scale operations. The States General chartered larger organisations—the Dutch West India Company and the Dutch East India Company—in the early seventeenth century to enlarge the scale of trading operations in the West Indies and the Orient respectively. These trading operations eventually became one of the largest and most extensive maritime trading companies at the time, and once held a virtual monopoly on strategic European shipping-routes westward through the Southern Hemisphere around South America through the Strait of Magellan, and eastward around Africa, past the Cape of Good Hope.[36] The companies' domination of global commerce contributed greatly to a commercial revolution and a cultural flowering in the Netherlands of the 17th century, known as the Dutch Golden Age. During the Dutch Golden Age, Dutch trade, science and art were among the most acclaimed in Europe.[37] Dutch military power was at its height in the middle of the 17th century and in that era the Dutch navy was the most powerful navy in the world.[38]

By the middle of the 17th century, the Dutch had overtaken Portugal as the dominant player in the spice and silk trade, and in 1652 founded a colony at Cape Town on the coast of South Africa, as a way-station for its ships on the route between Europe and Asia. After the first settlers spread out around the Company station, nomadic white livestock farmers, or Trekboers, moved more widely afield, leaving the richer, but limited, farming lands of the coast for the drier interior tableland. Between 1602 and 1796, many Europeans were sent to work in the Asia trade. The majority died of disease or made their way back to Europe, but some of them made the Indies their new home. Interaction between the Dutch and native population mainly took place in Sri Lanka and the modern Indonesian Islands. In some Dutch colonies there are major ethnic groups of Dutch ancestry descending from emigrated Dutch settlers. In South Africa the Boers and Cape Dutch are collectively known as the Afrikaners. The Burgher people of Sri Lanka and the Indo people of Indonesia as well as the Creoles of Suriname are mixed race people of Dutch descent. In the USA there have been three American presidents of Dutch descent: Martin Van Buren, the first president who was not of British descent, and whose first language was Dutch, the 26th president Theodore Roosevelt, and Franklin D. Roosevelt, the 32nd president, elected to four terms in office (1933 to 1945) and the only U.S. president to have served more than two terms.

In their search for new trade passages between Asia and Europe, Dutch navigators explored and charted distant regions such as Australia, New Zealand, Tasmania, and parts of the eastern coast of North America.[39] During the period of proto-industrialization, the empire received 50% of textiles and 80% of silks import from the India's Mughal Empire, chiefly from its most developed region known as Bengal Subah.[40][41][42][43]

In the 18th century, the Dutch colonial empire began to decline as a result of the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War of 1780–1784, in which the Dutch Republic lost a number of its colonial possessions and trade monopolies to the British Empire, along with the conquest of the Mughal Bengal at the Battle of Plassey by the East India Company.[44][45][46] Nevertheless, major portions of the empire survived until the advent of global decolonisation following World War II, namely the East Indies and Dutch Guiana.[47] Three former colonial territories in the West Indies islands around the Caribbean Sea—Aruba, Curaçao, and Sint Maarten—remain as constituent countries represented within the Kingdom of the Netherlands.[47]

Ottoman Empire (Turkey) (1453–1918)[edit]

The Ottoman Empire was a Turkic state, which at the height of its power (16th–17th centuries) spanned three continents (see: extent of Ottoman territories) controlling parts of Southeastern Europe, the Middle East and most of North Africa.[48] The empire has been called by historians a "Universal Empire" due to both Roman and Islamic traditions.[49] It was the head of the Gunpowder Empires.

The empire was at the center of interactions between the Eastern and Western worlds for six centuries. The Ottoman Empire was the only Islamic power to seriously challenge the rising power of Western Europe between the 15th and 19th centuries. With Istanbul (or Constantinople) as its capital, the Empire was in some respects an Islamic successor of earlier Mediterranean empires—the Roman and Byzantine empires.

Ottoman military reform efforts begin with Selim III (1789–1807) who made the first major attempts to modernize the army along European lines. These efforts, however, were hampered by reactionary movements, partly from the religious leadership, but primarily from the Janissary corps, who had become anarchic and ineffectual. Jealous of their privileges and firmly opposed to change, they created a Janissary revolt. Selim's efforts cost him his throne and his life, but were resolved in spectacular and bloody fashion by his successor, the dynamic Mahmud II, who massacred the Janissary corps in 1826.

The effective military and bureaucratic structures of the previous century also came under strain during a protracted period of misrule by weak Sultans. But in spite of these difficulties, the Empire remained a major expansionist power until the Battle of Vienna in 1683, which marked the end of Ottoman expansion into Europe. Much of the decline took place in the 19th century under pressure from Russia. Egypt and the Balkans were lost by 1913, and the Empire disintegrated after the First World War, leaving Turkey as the successor state.[50]

Mughal Empire (1526–1857)[edit]

The Mughal Empire was founded in 1526 by Babur of the Barlas clan after his victories at the First Battle of Panipat and the Battle of Khanwa against the Delhi Sultanate and Rajput Confederation.[51][52] Over the next centuries under Akbar, Jahangir, Shah Jahan, the mughal empire would grow in area and power and dominate the Indian subcontinent reaching its maximum extent under Emperor Aurangzeb. This imperial structure lasted until 1720, shortly after the Mughal-Maratha Wars and the death of Aurangzeb,[53][54] losing its influence to reveal powers such as the Maratha Empire and the Sikh Confederacy. The empire was formally dissolved by the British Raj after the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

Indian subcontinent was producing about 25% of the world's industrial output from 1st millennium CE up to until the 18th century.[55] The exchequer of the Emperor Aurangzeb reported an annual revenue of more than £100 million, or $450 million, making him one of the wealthiest monarchs in the world at the time.[56][57] The empire had an extensive road network, which was vital to the economic infrastructure, built by a public works department set up by the Mughals, linking towns and cities across the empire, making trade easier to conduct.[58]

The Mughals adopted and standardised the rupee (rupiya, or silver) and dam (copper) currencies introduced by Sur Emperor Sher Shah Suri during his brief rule.[59] The currency was initially 48 dams to a single rupee in the beginning of Akbar's reign, before it later became 38 dams to a rupee in the 1580s, with the dam's value rising further in the 17th century as a result of new industrial uses for copper, such as in bronze cannons and brass utensils. The dam's value was later worth 30 to a rupee towards the end of Jahangir's reign, and then 16 to a rupee by the 1660s.[60] The Mughals minted coins with high purity, never dropping below 96%, and without debasement until the 1720s.[61]

A major sector of the Mughal economy was agriculture.[58] A variety of crops were grown, including food crops such as wheat, rice, and barley, and non-food cash crops such as cotton, indigo and opium. By the mid-17th century, Indian cultivators begun to extensively grow imported from the Americas, maize and tobacco.[58] The Mughal administration emphasised agrarian reform, started by Sher Shah Suri, the work of which Akbar adopted and furthered with more reforms. The civil administration was organised in a hierarchical manner on the basis of merit, with promotions based on performance, exemplified by the common use of the seed drill among Indian peasants,[62] and built irrigation systems across the empire, which produced much higher crop yields and increased the net revenue base, leading to increased agricultural production.[58]

Manufacturing was also a significant contributor to the Mughal Economy. The Mughal empire produced about 25% of the world's industrial output up until the end of the 18th century.[55] Manufactured goods and cash crops from the Mughal Empire were sold throughout the world. Key industries included textiles, shipbuilding, and steel. Processed products included cotton textiles, yarns, thread, silk, jute products, metalware, and foods such as sugar, oils and butter[58] The Mughal Empire also took advantage of the demand of products from Mughal India in Europe, particularly cotton textiles, as well as goods such as spices, peppers, indigo, silks, and saltpeter (for use in munitions).[58] European fashion, for example, became increasingly dependent on Mughal Indian textiles and silks. From the late 17th century to the early 18th century, Mughal India accounted for 95% of British imports from Asia, and the Bengal Subah province alone accounted for 40% of Dutch imports from Asia.[63]

The largest manufacturing industry in the Mughal Empire was textile manufacturing, particularly cotton textile manufacturing, which included the production of piece goods, calicos, and muslins, Indian cotton textiles were the most important manufactured goods in world trade in the 18th century, consumed across the world from the Americas to Japan.[64] By the early 18th century, Mughal Indian textiles were clothing people across the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, Europe, the Americas, Africa, and the Middle East.[65] The most important centre of cotton production was the Bengal province, particularly around its capital city of Dhaka.[66]

Papacy and Papal States (1420–1648)[edit]

The Papacy was considered one of the great powers of the age by important thinkers such as Machiavelli and Giovanni Botero. The Papal States covered central Italy and were expanded by warrior popes such as Julius II. Italy, although divided in several states, saw a period of great prosperity during the Renaissance. In 1420, Pope Martin V re-established Rome as the sole seat of the Catholic Church and put an end to the Western Schism. Between 1494 and the second half of the 16th century, Italy was the battleground of Europe. Competing monarchs, including Popes, clashed for European supremacy in Italy. In the late 1500s and early 1600s, the Papacy led the Counter-reformation effort. Pontiffs such as Paul III and Pius V, exercised great diplomatic influence in Europe. Popes mediated the Peace of Nice (1538) between the Holy Roman Empire and France, as well as the Peace of Vervins (1598) between France and Spain. In the new world, thousands were converted to Catholicism by missionaries. Many European and Italian states (such as the Republic of Venice and the Republic of Genoa) were brought by the Papacy into "Holy Leagues" to defeat the Ottoman Empire: defeats occurred in Rhodes (1522), Preveza (1538), Budapest (1541), Algiers (1541), whereas victories took place at Vienna (1529), Tunis (1535), Lepanto (1571), and Malta (1565). Similarly, the Church supported Catholic leagues in the European wars of religion fought in France, the Low Countries, and Germany. France remained Catholic following the conversion of the French king, whereas half of the Low Countries were lost to Protestantism. It was the 30 years war that ultimately ended the status of the Papacy as a great power. Although the Pope declared Westphalia "null and void", European rulers refused to obey Papal orders and even rejected Papal mediation at the negotiations of the treaty.

Toungoo Empire of Burma (1510–1599)[edit]

The First Toungoo Empire (Burmese: တောင်ငူ ခေတ်, [tàʊɴŋù kʰɪʔ]; also known as the First Toungoo Dynasty, the Second Burmese Empire or simply the Toungoo Empire) was the dominant power in mainland Southeast Asia in the second half of the 16th century. At its peak, Toungoo "exercised suzerainty from Manipur to the Cambodian marches and from the borders of Arakan to Yunnan" and was "probably the largest empire in the history of Southeast Asia".[67] The Toungoo Dynasty was the "most adventurous and militarily successful" in Burmese history, but it was also the "shortest-lived".[68]

The empire grew out of the principality of Toungoo, a minor vassal state of Ava until 1510. The landlocked petty state began its rise in the 1530s under Tabinshwehti who went on to found the largest polity in Myanmar since the Pagan Empire by 1550. His more celebrated successor Bayinnaung then greatly expanded the empire, conquering much of mainland Southeast Asia by 1565. He spent the next decade keeping the empire intact, putting down rebellions in Siam, Lan Xang and the northernmost Shan states. From 1576 onwards, he declared a large sphere of influence in westerly lands—trans-Manipur states, Arakan and Ceylon. The empire, held together by patron-client relationships, declined soon after his death in 1581. His successor Nanda never gained the full support of the vassal rulers, and presided over the empire's precipitous collapse in the next 18 years.

The First Toungoo Empire marked the end of the period of petty kingdoms in mainland Southeast Asia. Although the overextended empire proved ephemeral, the forces that underpinned its rise were not. Its two main successor states—Restored Toungoo Burma and Ayutthaya Siam—went on to dominate western and central mainland Southeast Asia, respectively, down to the mid-18th century.

Iran[edit]

Safavid Empire (1501–1736)[edit]

The Safavid Empire was one of the most significant ruling dynasties of Iran. They ruled one of the greatest Iranian Empires after the Muslim conquest of Persia.[69][70][71][72] The Safavids ruled from 1501 to 1736 and at their height, they controlled all of modern Iran, Azerbaijan and Armenia, most of Iraq, Georgia, Afghanistan, and the Caucasus, as well as parts of modern-day Pakistan, Turkmenistan and Turkey. Safavid Iran was one of the Islamic "gunpowder empires". The Safavid Empire originated from Ardabil in Iran and had its origins in a long established Sufi order, called the Safaviyeh. The Safavids established an independent unified Iranian state for the first time after the Muslim conquest of Persia and reasserted Iranian political identity, and established Shia Islam as the official religion in Iran.

Despite their demise in 1736, the legacy that they left behind was the revival of Iran as an economic stronghold between East and West, the establishment of an efficient state and bureaucracy based upon "checks and balances", their architectural innovations and their patronage for fine arts. The Safavids have also left their mark down to the present era by spreading Shi'a Islam in Iran, as well as major parts of the Caucasus, Mesopotamia, and Anatolia.

Afsharid Empire (1736–1796)[edit]

The Afsharid dynasty was an Iranian dynasty that originated from the Afshar tribe in Iran's north-eastern province of Khorasan, ruling Iran in the mid-eighteenth century. The dynasty was founded in 1736 by the military genius Nader Shah,[73] who deposed the last member of the Safavid dynasty and proclaimed himself as the Shah of Iran. At its peak, the empire was arguably the most powerful in the world.[74] During Nader's reign, Iran reached its greatest extent since the Sasanian Empire. At its height it controlled modern-day Iran, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan Republic, parts of the North Caucasus (Dagestan), Afghanistan, Bahrain, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Pakistan, and parts of Iraq, Turkey, United Arab Emirates and Oman.

Polish Empire (1410–1699)[edit]

The union of the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, formed in 1385, emerged as a major power in Central and Eastern Europe following its victory at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410.[75][76][77] Poland–Lithuania covered a large territory in Central and Eastern Europe, making it the largest state in Europe at the time.[77] Through its territorial possessions and vassal principalities and protectorates, its influence extended from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, reaching Livonia (present-day Estonia and Latvia) in the north,[78] and Moldavia and Crimea in the south and southeast.[79][80] In the 15th century the ruling Jagiellonian dynasty managed to place its members on the thrones of the neighbouring kingdoms of Bohemia and Hungary, becoming one of the most powerful houses in Europe.[81]

The Rzeczpospolita was one of the largest, most powerful and most populous[82] countries in 16th, 17th, and 18th century Europe. In fact, Poland was a major power that imposed its will on weaker neighbors. Its political structure was formed in 1569 by the Union of Lublin, which transformed the previous Polish–Lithuanian union into the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and lasted in this form until the adoption of the Constitution of May 3, 1791. In the 16th century, the area of the Rzeczpospolita reached almost 1 million km2, with a population of 11 million. At that time, it was the third largest country in Europe, and the largest country of Western Christian Europe.[83] Poland was a political, military and economic power. The Union possessed features unique among contemporary states. This political system unusual for its time stemmed from the ascendance of the szlachta noble class over other social classes and over the political system of monarchy. In time, the szlachta accumulated enough privileges (such as those established by the Nihil novi Act of 1505) that no monarch could hope to break the szlachta's grip on power. The Commonwealth's political system does not readily fit into a simple category; it may best be described as a melange of:

- confederation and federation, with regard to the broad autonomy of its regions. It is, however, difficult to decisively call the Commonwealth either confederation or federation, as it had some qualities of both of them;

- oligarchy, as only the szlachta—around 15% of the population—had political rights;

- democracy, since all the szlachta were equal in rights and privileges, and the Sejm could veto the king on important matters, including legislation (the adoption of new laws), foreign affairs, declaration of war, and taxation (changes of existing taxes or the levying of new ones). Also, the 9% of Commonwealth population who enjoyed those political rights (the szlachta)[84] was a substantially larger percentage than in majority European countries;[85] note that in 1789 in France only about 1% of the population had the right to vote, and in 1867 in the United Kingdom, only about 3%.[84][85]

- elective monarchy, since the monarch, elected by the szlachta, was Head of State;

- constitutional monarchy, since the monarch was bound by pacta conventa and other laws, and the szlachta could disobey decrees of the king that they deemed illegal.

The Polish "Golden Age", in the reigns of Sigismund I and Sigismund II, the last two Jagiellonian kings, and more generally the 16th century, is identified with the culture of the Polish Renaissance. This flowering had its material base in the prosperity of the elites, both the landed nobility and urban patriciate at such centers as Kraków and Gdańsk. The University of Kraków became one of the leading centers of learning in Europe, and in Poland Nicolaus Copernicus formulated a model of the universe that placed the Sun rather than Earth at its center, making a groundbreaking contribution, which sparked the Scientific Revolution in Europe.[77][81] Following the Union of Lublin, at various times, through personal unions and vassalages, Poland's sphere of influence reached Sweden and Finland in Northern Europe, the Danube in Southeastern Europe,[86][87] and the Caribbean and West Africa. After victories in the Dimitriads (the Battle of Klushino, 1610), with Polish forces entering Moscow, Sigismund III's son, Prince Władysław of Poland, was briefly elected Tsar of Russia.

The victory of Polish-led forces at the Battle of Vienna in 1683 saved Austria from Ottoman conquest and marked the end of Ottoman advances into Europe.[88][89]

Swedish Empire (1611–1721)[edit]

Sweden emerged as a great European power under Axel Oxenstierna and King Gustavus Adolphus. As a result of acquiring territories seized from Russia and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, as well as its involvement in the Thirty Years' War, Sweden found itself transformed into the leader of Protestantism. The mid-17th and early 18th centuries were Sweden's most successful years as a great power. Sweden also had colonial possessions as a minor colonial Empire that existed from 1638 to 1663 and later from 1784 to 1878. Sweden founded overseas colonies, principally in the New World. New Sweden was founded in the valley of the Delaware River in 1638, and Sweden later laid claim to a number of Caribbean islands. A string of Swedish forts and trading posts was constructed along the coast of West Africa as well, but these were not designed for Swedish settlers.

Sweden reached its largest territorial extent during the rule of Charles X (1622–1660) after the treaty of Roskilde in 1658. After half a century of expansive warfare, the Swedish economy had deteriorated. It would become the lifetime task of Charles' son, Charles XI (1655–1697), to rebuild the economy and refit the army. His legacy to his son, the coming ruler of Sweden Charles XII, was one of the finest arsenals in the world, with a large standing army and a great fleet. Sweden's largest threat at this time, Russia, had a larger army but was far behind in both equipment and training. The Swedish army crushed the Russians at the Battle of Narva in 1700, one of the first battles of the Great Northern War. This led to an overambitious campaign against Russia in 1707, however, ending in a decisive Russian victory at the Battle of Poltava (1709). The campaign had a successful opening for Sweden, which came to occupy half of Poland and Charles laid claim to the Polish throne. But after a long march exposed by cossack raids, the Russian Tsar Peter the Great's scorched-earth techniques and the very cold Russian climate, the Swedes stood weakened with shattered confidence and enormously outnumbered by the Russian army at Poltava.[90][91]

During the Thirty Years' War, Sweden managed to conquer approximately half of the member states of the Holy Roman Empire. The fortunes of war would shift back and forth several times. After its defeat in the Battle of Nördlingen (1634), confidence in Sweden among the Swedish-controlled German states was damaged, and several of the provinces refused further Swedish military support, leaving Sweden with only a couple of northern German provinces. After France intervened on the same side as Sweden, fortunes shifted again. As the war continued, the civilian and military death toll grew, and when it was over, it led to severe depopulation in the German states. Although exact population estimates do not exist, historians estimate that the population of the Holy Roman Empire fell by one-third as a result of the war.[92]

Egypt (1805–1882, 1882–1914)[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2023) |

The Egyptian Khedivate was a major world and regional power which began to emerge starting from the defeat and expulsion of Napoleon Bonaparte from Egypt. This modern-age Egyptian Empire has expanded to control several countries and nations including present-day Sudan, South Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti, northern Somalia, Israel, Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Greece, Cyprus, southern and central Turkey, in addition to parts from Libya, Chad, Central African Republic, and Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as northwestern Saudi Arabia, parts of Yemen and the Kingdom of Hejaz. During that era, Egypt has succeeded to re-emerged again to its previous centuries-long glory as a global Islamic power to an extent that was even stronger and healthier than the fading Ottoman Empire. Egypt maintained its status as a regional power until the British occupation of the country after the Anglo-Egyptian War.

The Egyptian-based Albanian Muhammad Ali dynasty has brought several social, educational, political, economic, judicial, strategic and military reforms that have deeply depended on the human resources of Egyptians as the native powerhouse of the country instead of depending on foreigner Circassians and Turks who were associated with the Ottoman warlords during the Ottoman control of Egypt. With the emerging world-class national Egyptian industries, the Egyptian Army has showed an international level of prowess to the extent that it was the major Islamic military in the Islamic World. Egypt became also one of the first countries in the world to introduce railway transportation.

Egypt has been successful in reforming its economy to become based on developed agriculture and modernised industries. A big number of factories have been set up and new Nile canals have been dug to increase the surface area of Egyptian fertile arable land. Another notable fact of the internationally competitive economic progress of Egypt during that era was the development of new cultivations such as Cotton, Mango and many other crops. The legacy of these agricultural advancements was the base of Egypt's current success in taking its rightful place as one of the best sources of high-quality cotton on a global scale.

High modern great powers[edit]

Second British Empire[edit]

The Second British Empire was built primarily in Asia, the Middle East and Africa after 1800. It included colonies in Canada, the Caribbean, and India, and shortly thereafter began the settlement of Australia and New Zealand. Following France's 1815 defeat in the Napoleonic Wars, Great Britain took possession of many more overseas territories in Africa and Asia, and established informal empires of free trade in South America, Persia, etc.

At its height the British Empire was the largest empire in history and, for over a century, was the foremost global power. In 1815–1914 the Pax Britannica was the most powerful unitary authority in history due to the Royal Navy's unprecedented naval predominance.[94]

During the 19th century, the United Kingdom was the first country in the world to industrialise and embrace free trade, giving birth to the Industrial Revolution. The rapid industrial growth after the conquests of the wealthy Mughal Bengal transformed Great Britain into the world's largest industrial and financial power, while the world's largest navy gave it undisputed control of the seas and international trade routes, an advantage which helped the British Empire, after a mid-century liberal reaction against empire-building, to grow faster than ever before. The Victorian empire colonised large parts of Africa, including such territories as South Africa, Egypt, Kenya, Sudan, Nigeria, and Ghana, most of Oceania, colonies in the Far East, such as Singapore, Malaysia, and Hong Kong, and took control over the whole Indian subcontinent, making it the largest empire in the world.[95]

After victory in the First World War, the Empire gained control of territories such as Tanzania and Namibia from the German Empire, and Iraq and Palestine (including the Transjordan) from the Ottoman Empire. By this point in 1920 the British empire had grown to become the largest empire in history, controlling approximately 25% of the world's land surface and 25% of the world's population.[93] It covered about 36.6 million km2 (14.1 million sq mi). Because of its magnitude, it was often referred to as "the empire on which the sun never sets".[96]

The political and social changes and economic disruption in the United Kingdom and throughout the world caused by First World War followed only two decades later by the Second World War caused the Empire to gradually break up as colonies were given independence. Much of the reason the Empire ceased was because many colonies by the mid-20th century were no longer as undeveloped as at the arrival of British control nor as dependent and social changes throughout the world during the first half of the 20th century gave rise to national identity. The British Government, reeling from the economic cost of two successive world wars and changing social attitudes towards empire, felt it could no longer afford to maintain it if the country were to recover economically, pay for the newly created welfare state, and fight the newly emerged Cold War with the Soviet Union.

The influence and power of the British Empire dropped dramatically after the Second World War, especially after the Partition of India in 1947 and the Suez Crisis in 1956. The Commonwealth of Nations is the successor to the Empire, where the United Kingdom is an equal member with all other states.

France[edit]

France was a dominant empire possessing many colonies in various locations around the world. The French colonial empire is the set of territories outside Europe that were under French rule primarily from the 17th century to the late 1960s (some see the French control of places such as New Caledonia as a continuation of that colonial empire). The first French colonial empire reached its peak in 1680 at over 10,000,000 km2 (3,900,000 sq mi), which at the time, was the second largest in the world behind the Spanish Empire. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the colonial empire of France was the second largest in the world behind the British Empire. The French colonial empire extended over 13,500,000 km2 (5,200,000 sq mi) of land at its height in the 1920s and 1930s. Including metropolitan France, the total amount of land under French sovereignty reached 13,500,000 km2 (5,200,000 sq mi) at the time, which is 10.0% of the Earth's total land area.

The total area of the French colonial empire, with the first (mainly in the Americas and Asia) and second (mainly in Africa and Asia), the French colonial empires combined, reached 24,000,000 km2 (9,300,000 sq mi), the second largest in the world (the first being the British Empire).

France began to establish colonies in North America, the Caribbean and India, following Spanish and Portuguese successes during the Age of Discovery, in rivalry with Britain for supremacy. A series of wars with Britain during the 18th and early 19th centuries which France lost ended its colonial ambitions on these continents, and with it is what some historians term the "first" French colonial empire. In the 19th century, France established a new empire in Africa and South East Asia. Some of these colonies lasted beyond the Second World War.

Late Spanish Empire[edit]

After the Napoleonic period the Bourbon dynasty was restored in Spain and over the huge number of Spanish territories around the world. But the shock of the Peninsular War sparked declarations of independence in the Latin America controlled by Spain and by 1835 successive revolutions had signed the end of the Spanish rule over the majority of this countries. Spain retained fragments of its empire in the Caribbean (Cuba and Puerto Rico); Asia (Philippines); and Oceania (Guam, Micronesia, Palau, and Northern Marianas) until the Spanish–American War of 1898. Spanish participation in the Scramble for Africa was minimal: Spanish Morocco was held until 1956 and Spanish Guinea and the Spanish Sahara were held until 1968 and 1975 respectively. The Canary Islands, Ceuta, Melilla and the other Plazas de Soberanía on the northern African coast have remained part of Spain.

Austrian Empire (and Austria-Hungary)[edit]

The Habsburg Empire became one of the key powers in Europe after the Napoleonic wars, with a sphere of influence stretching over Central Europe, Germany, and Italy. During the second half of the 19th century, the Habsburgs could not prevent the unification of Italy and Germany. Eventually, the complex internal power struggle resulted in the establishment of a so-called dual monarchy between Austria and Hungary. Following the defeat and dissolution of the monarchy after the First World War, both Austria and Hungary became independent and self-governing countries (First Austrian Republic, Kingdom of Hungary). Other political entities emerged from the destruction of the Great War including Poland, Czechoslovakia, and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes.

Prussia and Germany[edit]

The Kingdom of Prussia attained its greatest importance in the 18th and 19th centuries, when it conquered various territories previously held by Sweden,[97][98] Austria, Poland, France, Denmark, and various minor German principalities.[99] It became a European great power under the reign of Frederick II of Prussia (1740–1786).[99] It dominated northern Germany politically, economically, and in terms of population, and played a key role in the unification of Germany in 1871 (see Prussia and Germany section below).

After the territorial acquisitions of the Congress of Vienna (1815), the Kingdom of Prussia became the only great power with a majority German-speaking population.[99] During the 19th century, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck pursued a policy of uniting the German principalities into a "Lesser Germany" which would exclude the Austrian Empire. Prussia was the core of the North German Confederation formed in 1867, which became part of the German Empire or Deutsches Reich in 1871 when the southern German states, excluding Austria, were added.

After 1850, the states of Germany had rapidly become industrialized, with particular strengths in coal, iron (and later steel), chemicals, and railways. In 1871, Germany had a population of 41 million people; by 1913, this had increased to 68 million. A heavily rural collection of states in 1815, the now united Germany became predominantly urban.[100] The success of German industrialization manifested itself in two ways since the early 20th century: The German factories were larger and more modern than their British and French counterparts.[101] The dominance of the German Empire in natural sciences, especially in physics and chemistry was such that one[clarification needed] of all Nobel Prizes went to German inventors and researchers. During its 47 years of existence, the German Empire became the industrial, technological, and scientific giant of Europe, and by 1913, Germany was the largest economy in Continental Europe and the third-largest in the world.[102] Germany also became a great power, it built up the longest railway network of Europe, the world's strongest army,[103] and a fast-growing industrial base.[104] Starting very small in 1871, in a decade, the navy became second only to Britain's Royal Navy. After the removal of Otto von Bismarck by Wilhelm II in 1890, the empire embarked on Weltpolitik – a bellicose new course that ultimately contributed to the outbreak of World War I.

Wilhelm II wanted Germany to have her "place in the sun", like Britain, which he constantly wished to emulate or rival.[105] With German traders and merchants already active worldwide, he encouraged colonial efforts in Africa and the Pacific ("new imperialism"), causing the German Empire to vie with other European powers for remaining "unclaimed" territories. With the encouragement or at least the acquiescence of Britain, which at this stage saw Germany as a counterweight to her old rival France, Germany acquired German Southwest Africa (modern Namibia), German Kamerun (modern Cameroon), Togoland (modern Togo) and German East Africa (modern Rwanda, Burundi, and the mainland part of current Tanzania). Islands were gained in the Pacific through purchase and treaties and also a 99-year lease for the territory of Kiautschou in northeast China. But of these German colonies only Togoland and German Samoa (after 1908) became self-sufficient and profitable; all the others required subsidies from the Berlin treasury for building infrastructure, school systems, hospitals and other institutions.

After the World War I broke out, Germany participated in the war as a part of the Central Powers. At its height, Germany occupied Belgium and parts of France, as well as acquired Ukraine and the Baltic States in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Soon, Germany lost its status as a great power in the Treaty of Versailles as it ceded some of its territories and all of its overseas territories to the Britain and France, as well as gave up part of its military.[106][n. 1][107][n. 2][n. 3][n. 4][n. 5][n. 6][108][n. 7][n. 8]

Germany rose back to be a great power in 1933, when the Nazi Germany replaced the Weimar Republic as the new government of Germany. The most pressing economic matter the Nazis initially faced was the 30 per cent national unemployment rate.[109] Economist Dr. Hjalmar Schacht, President of the Reichsbank and Minister of Economics, created a scheme for deficit financing in May 1933. Capital projects were paid for with the issuance of promissory notes called Mefo bills. When the notes were presented for payment, the Reichsbank printed money. Hitler and his economic team expected that the upcoming territorial expansion would provide the means of repaying the soaring national debt.[110] Schacht's administration achieved a rapid decline in the unemployment rate, the largest of any country during the Great Depression.[109] Economic recovery was uneven, with reduced hours of work and erratic availability of necessities, leading to disenchantment with the regime as early as 1934.[111]

In October 1933, the Junkers Aircraft Works was expropriated. In concert with other aircraft manufacturers and under the direction of Aviation Minister Göring, production was ramped up. From a workforce of 3,200 people producing 100 units per year in 1932, the industry grew to employ a quarter of a million workers manufacturing over 10,000 technically advanced aircraft annually less than ten years later.[112]

An elaborate bureaucracy was created to regulate imports of raw materials and finished goods with the intention of eliminating foreign competition in the German marketplace and improving the nation's balance of payments. The Nazis encouraged the development of synthetic replacements for materials such as oil and textiles.[113] As the market was experiencing a glut and prices for petroleum were low, in 1933 the Nazi government made a profit-sharing agreement with IG Farben, guaranteeing them a 5 per cent return on capital invested in their synthetic oil plant at Leuna. Any profits in excess of that amount would be turned over to the Reich. By 1936, Farben regretted making the deal, as excess profits were by then being generated.[114] In another attempt to secure an adequate wartime supply of petroleum, Germany intimidated Romania into signing a trade agreement in March 1939.[115]

Major public works projects financed with deficit spending included the construction of a network of Autobahnen and providing funding for programmes initiated by the previous government for housing and agricultural improvements.[116] To stimulate the construction industry, credit was offered to private businesses and subsidies were made available for home purchases and repairs.[117] On the condition that the wife would leave the workforce, a loan of up to 1,000 Reichsmarks could be accessed by young couples of Aryan descent who intended to marry, and the amount that had to be repaid was reduced by 25 per cent for each child born.[118] The caveat that the woman had to remain unemployed outside the home was dropped by 1937 due to a shortage of skilled labourers.[119]

Envisioning widespread car ownership as part of the new Germany, Hitler arranged for designer Ferdinand Porsche to draw up plans for the KdF-wagen (Strength Through Joy car), intended to be an automobile that everyone could afford. A prototype was displayed at the International Motor Show in Berlin on 17 February 1939. With the outbreak of World War II, the factory was converted to produce military vehicles. None were sold until after the war, when the vehicle was renamed the Volkswagen (people's car).[120]

Six million people were unemployed when the Nazis took power in 1933 and by 1937 there were fewer than a million.[121] This was in part due to the removal of women from the workforce.[122] Real wages dropped by 25 per cent between 1933 and 1938.[109] After the dissolution of the trade unions in May 1933, their funds were seized and their leadership arrested,[123] including those who attempted to co-operate with the Nazis.[124] A new organisation, the German Labour Front, was created and placed under Nazi Party functionary Robert Ley.[123] The average work week was 43 hours in 1933; by 1939 this increased to 47 hours.[125]

By early 1934, the focus shifted towards rearmament. By 1935, military expenditures accounted for 73 per cent of the government's purchases of goods and services.[126] On 18 October 1936, Hitler named Göring as Plenipotentiary of the Four Year Plan, intended to speed up rearmament.[127] In addition to calling for the rapid construction of steel mills, synthetic rubber plants, and other factories, Göring instituted wage and price controls and restricted the issuance of stock dividends.[109] Large expenditures were made on rearmament in spite of growing deficits.[128] Plans unveiled in late 1938 for massive increases to the navy and air force were impossible to fulfil, as Germany lacked the finances and material resources to build the planned units, as well as the necessary fuel required to keep them running.[129] With the introduction of compulsory military service in 1935, the Reichswehr, which had been limited to 100,000 by the terms of the Versailles Treaty, expanded to 750,000 on active service at the start of World War II, with a million more in the reserve.[130] By January 1939, unemployment was down to 301,800 and it dropped to only 77,500 by September.[131]

After triumphing in economic success, the Nazis started a hostile foreign expansion policy. They first sent troops to occupy the demilitarized Rhineland in 1936, then annexed Austria and Sudetenland of Czechoslovakia in 1938. In 1939, they further annexed the Czech part of Czechoslovakia and founded the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, and annexed the Lithuanian port city of Klaipėda. The Slovak part of Czechoslovakia declared independence under German support and the Slovak Republic is established.

World War II broke out in 1939, when Germany invaded Poland with the Soviet Union. After occupying Poland, Germany started the conquest of Europe, and occupied Belgium, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, France and the British Channel Islands in 1940, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Greece and Yugoslavia in 1941, Italy, Albania, Montenegro and Monaco in 1943, and Hungary in 1944. The French government continued to operate after the defeat, but was actually a client state of Germany.

Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, only to face defeat. This marks the start of the collapse of the German Reich. On 8 May 1945, Nazi Germany officially surrendered and marks the end of the Nazi Regime.

United States[edit]

The United States of America has exercised and continues to exercise worldwide economic, cultural, and military influence.

Founded in 1776 by thirteen coastal colonies that declared their independence from Great Britain, the United States began its western expansion following the end of the American Revolutionary War and the recognition of U.S. sovereignty in the 1783 Treaty of Paris. The treaty bequeathed to the nascent republic all land between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River, and Americans began migrating there in large numbers at the end of the 18th Century, resulting in the displacement of Native American cultures, often through native peoples' forcible deportation and violent wars of eviction. These efforts at expansion were greatly strengthened by the 1787 Constitutional Convention, which resulted in the ratification of the United States Constitution and transformed the U.S. from a loose confederation of semi-autonomous states into a federal entity with a strong national core. In 1803, the United States acquired Louisiana from France, doubling the country's size and extending its borders to the Rocky Mountains.

American power and population grew rapidly, so that by 1823 President James Monroe felt confident enough to issue his Monroe Doctrine, which proclaimed the Americas as the express sphere of the United States and threatened military action against any European power that attempted to make advances in the area. This was the beginning of the U.S.'s emergence as a regional power in North America. That process was confirmed in the Mexican–American War of 1846–1848, in which the United States, following a skirmish between Mexican and U.S. forces in land disputed between Mexico and the U.S., invaded Mexico. The war, which included the deployment of U.S. forces into Mexico, the taking of Veracruz by sea, and the occupation of Mexico City by American troops (which finally resulted in Mexico's defeat), stunned much of the world. In the peace treaty (Treaty of Guadelupe Hidalgo) that followed, the U.S. annexed the northern half of Mexico, comprising what is now the Southwestern United States. During the course of the war, the United States also negotiated by treaty the acquisition of the Oregon Territory's southern half from Great Britain. In 1867, William H. Seward, the U.S. Secretary of State, negotiated the purchase of Alaska from the Russian Empire. The United States defeated Spain in the Spanish–American War in 1898, and gained the possessions of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. The territory of Hawaii was also acquired in 1898. The United States became a major victorious power in both World Wars, and became a major economic power after World War I tires out the European powers.[132]

Russian Empire and Soviet Union[edit]

The Russian Empire as a state, existed from 1721 until it was declared a republic 1 September 1917. The Russian Empire was the successor to the Tsardom of Russia and the predecessor of the Soviet Union. It was one of the largest empires in world history, surpassed in landmass only by the British and Mongolian empires: at one point in 1866, it stretched from Northern Europe across Asia and into North America.

At the beginning of the 19th century the Russian Empire extended from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Black Sea on the south, from the Baltic Sea on the west to the Pacific Ocean on the east. With 125.6 million subjects registered by the 1897 census, it had the third largest population of the world at the time, after Qing China and the British Empire. Like all empires it represented a large disparity in economic, ethnic, and religious positions. Its government, ruled by the Emperor, was one of the last absolute monarchies in Europe. Prior to the outbreak of World War I in August 1914 Russia was one of the five major Great Powers of Europe.[134]

Following the October Revolution that overthrew the Russian Republic, the Soviet Union was established by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union began to resemble the old Russian Empire in landmass, with its territory stretching from Eastern Europe to Siberia, and from Northern Europe to Central Asia.

After the death of the first Soviet leader, Vladimir Lenin, in 1924, Joseph Stalin eventually won a power struggle and led the country through a large-scale industrialization with a command economy and political repression. On 23 August 1939, after unsuccessful efforts to form an anti-fascist alliance with Western powers, the Soviets signed the non-aggression agreement with Nazi Germany. After the start of World War II, the formally neutral Soviets invaded and annexed territories of several Central and Eastern European states, including eastern Poland, the Baltic states, northeastern Romania and eastern Finland.

In June 1941 the Germans invaded, opening the largest and bloodiest theater of war in history. Soviet war casualties accounted for the majority of Allied casualties of the conflict in the process of acquiring the upper hand over Axis forces at intense battles such as Stalingrad. Soviet forces eventually captured Berlin and won World War II in Europe on 9 May 1945. The territory overtaken by the Red Army became satellite states of the Eastern Bloc. The Cold War emerged in 1947, where the Eastern Bloc confronted the Western Bloc, which would unite in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization in 1949.

Following Stalin's death in 1953, a period known as de-Stalinization and the Khrushchev Thaw occurred under the leadership of Nikita Khrushchev. The country developed rapidly, as millions of peasants were moved into industrialized cities. The USSR took an early lead in the Space Race with the first ever satellite and the first human spaceflight and the first probe to land on another planet, Venus. In the 1970s, there was a brief détente of relations with the United States, but tensions resumed when the Soviet Union deployed troops in Afghanistan in 1979. The war drained economic resources and was matched by an escalation of American military aid to Mujahideen fighters.

In the mid-1980s, the last Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, sought to further reform and liberalize the economy through his policies of glasnost and perestroika. The goal was to preserve the Communist Party while reversing economic stagnation. The Cold War ended during his tenure and in 1989, Warsaw Pact countries in Eastern Europe overthrew their respective Marxist–Leninist regimes. Strong nationalist and separatist movements broke out across the USSR. Gorbachev initiated a referendum—boycotted by the Baltic republics, Armenia, Georgia, and Moldova—which resulted in the majority of participating citizens voting in favor of preserving the Union as a renewed federation. In August 1991, a coup d'état was attempted by Communist Party hardliners. It failed, with Russian President Boris Yeltsin playing a high-profile role in facing down the coup. The main result was the banning of the Communist Party. The republics led by Russia and Ukraine declared independence. On 25 December 1991, Gorbachev resigned. All the republics emerged from the dissolution of the Soviet Union as independent post-Soviet states. The Russian Federation (formerly the Russian SFSR) assumed the Soviet Union's rights and obligations and is recognized as its continued legal personality in world affairs.

The Soviet Union produced many significant social and technological achievements and innovations regarding military power. It boasted the world's second-largest economy and the largest standing military in the world.[135][136][137] The USSR was recognized as one of the five nuclear weapons states. It was a founding permanent member of the United Nations Security Council as well as a member of the OSCE, the WFTU and the leading member of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance and the Warsaw Pact.

Before its dissolution, the USSR had maintained its status as a world superpower alongside the United States, for four decades after World War II. Sometimes also called "Soviet Empire", it exercised its hegemony in Central and Eastern Europe and worldwide with military and economic strength, proxy conflicts and influence in developing countries and funding of scientific research, especially in space technology and weaponry.[138][139]

Italian Empire[edit]

Kingdom of Italy (dark green), Italian colonial empire (light green) and Italian occupied territories (grey).

The Italian colonial empire was created after the Kingdom of Italy joined other European powers in establishing colonies overseas during the "scramble for Africa". Modern Italy as a unified state only existed from 1861. By this time France, Spain, Portugal, Britain, and the Netherlands, had already carved out large empires over several hundred years. One of the last remaining areas open to colonisation was on the African continent.[140][141]

By the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Italy had annexed Eritrea and Somalia, and had wrested control of portions of the Ottoman Empire, including Libya, though it was defeated in its attempt to conquer Ethiopia. The Fascist regime under Italian dictator Benito Mussolini which came to power in 1922 sought to increase the size of the empire further. Ethiopia was successfully taken, four decades after the previous failure, and Italy's European borders were expanded. An official "Italian Empire" was proclaimed on 9 May 1936 following the conquest of Ethiopia.[142]

Italy sided with Nazi Germany during World War II but Britain soon captured Italian overseas colonies. By the time Italy itself was invaded in 1943, its empire had ceased to exist. On 8 September 1943 the Fascist regime of Mussolini collapsed, and a Civil War broke out between Italian Social Republic and Italian Resistance Movement, supported by Allied forces.

Empire of Japan[edit]

The Empire of Japan, officially the Empire of Great Japan or simply Great Japan (Dai Nippon), was an empire that existed from the Meiji Restoration on 3 January 1868 to the enactment of the post-World War II Constitution of Japan on 3 May 1947.

Imperial Japan's rapid industrialization and militarization under the slogan Fukoku Kyōhei (富国強兵, "Enrich the Country, Strengthen the Army") led to its emergence as a great power, eventually culminating in its membership in the Axis alliance and the conquest of a large part of the Asia-Pacific region. At the height of its power in 1942, the Japanese Empire ruled over a geographic area spanning 7,400,000 km2 (2,857,200 sq mi). This made it the 12th largest empire in history.[143]

In August 1914, former President of the United States William Howard Taft listed Japan and his country as the only two great powers uninvolved in World War I.[144] After winning wars against China (First Sino-Japanese War, 1894–95) and Russia (Russo-Japanese War, 1904–05) the Japanese Empire was considered to be one of the major powers worldwide. The maximum extent of the empire was gained during Second World War, when Japan conquered many Asian and Pacific countries (see Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere).

After suffering many defeats and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, however, the Empire of Japan surrendered to the Allies on 2 September 1945. A period of occupation by the Allies followed the surrender, and a new constitution was created with American involvement. The constitution came into force on 3 May 1947, officially dissolving the Empire. American occupation and reconstruction of the country continued well into the 1950s, eventually forming the current nation-state whose title is simply that ("the nation of Japan" Nippon-koku) or just "Japan".

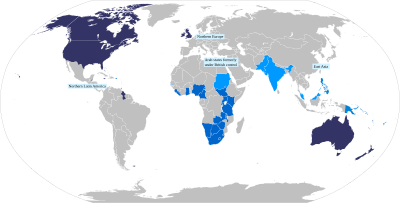

Post–Cold War era great powers[edit]

This section contains text that is written in a promotional tone. (May 2021) |

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Poor Grammar and Sentence Structure. (May 2021) |

United States[edit]

The United States was the foremost of the world's two superpowers during the Cold War. After the Cold War, the most common belief held that only the United States fulfilled the criteria to be considered a superpower.[145] Its geographic area composed the third or fourth-largest state in the world, with an area of approximately 9.37 million km2.[146] The population of the US was 248.7 million in 1990, at that time the fourth-largest nation.[147]

In the mid-to-late 20th century, the political status of the US was defined as a strongly capitalist federation and constitutional republic. It had a permanent seat on the United Nations Security Council plus two allies with permanent seats, the United Kingdom and France. The US had strong ties with capitalist Europe, Latin America, the British Commonwealth, and several East Asian countries (South Korea, Taiwan, Japan). It allied itself with both right-wing dictatorships and democracies.[148]