Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia

Μεγάλη Ἑλλάς (Ancient Greek) | |

|---|---|

|

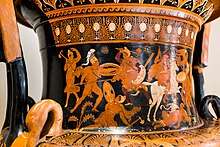

Clockwise from top left: Second Temple of Hera in Poseidonia, Campania; Doric-styled temple, Segesta, Sicily; Taras' sculpture of a young man wearing cucullus and leading his donkey, Louvre; depiction of Eos riding a two-horsed chariot, on a krater from Southern Italy, Staatliche Antikensammlungen. | |

| Etymology: from Ancient Greek and Latin ("Great[er] Greece") | |

Ancient Greek colonies and their dialect groupings in Magna Graecia. | |

| Present country | |

| Present territory | Southern Italy |

| Founded | 8th century BC |

| Founded by | Greeks |

| Largest city | Sybaris[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | city-states administered by the aristocracy |

| Demonym(s) | Italiote and Siceliote |

Magna Graecia[a] was the name given by the Romans to the Greek-speaking coastal areas of Southern Italy in the present-day Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania and Sicily; these regions were extensively populated by Greek settlers starting from the 8th century BC.[2]

The settlements in this region, founded initially by their metropoleis (mother cities), eventually evolved into strong Greek city-states (poleis), functioning independently. The settlers brought with them their Hellenic civilization, and developed their own civilisation of the highest level,[3] due to the distance from the motherland and the influence of the indigenous peoples of southern Italy[3] which left a lasting imprint on Italy (such as in the culture of ancient Rome). They also influenced the native peoples, such as the Sicels and the Oenotrians, who became hellenised after they adopted the Greek culture as their own. In some fields such as architecture and urban planning, they sometimes surpassed the mother country.[4] The ancient inhabitants of Magna Graecia are called Italiotes and Siceliotes.

Remains of some of these Greek cities can be seen today, such as Neapolis ("New City", now Naples), Syrakousai (Syracuse), Akragas (Agrigento), Taras (Taranto), Rhegion (Reggio Calabria), and Kroton (Crotone). The most populous city of Magna Graecia was Sybaris (now Sibari) with an estimated population, from 600 BC to 510 BC, between 300,000 and 500,000.[1]

The government of city-states was usually an aristocracy[5] and the cities were often at war with each other.[6]

The Second Punic War put an end to the independence of the cities of Magna Graecia, which were annexed to the Roman Republic in 205 BC.[7]

From the motherland Greece, art, literature and philosophy decisively influenced the life of the colonies. In Magna Graecia much impetus was given to culture, especially in some cities such as Taras (now Taranto).[5] Noteworthy was the South Italian ancient Greek pottery, fabricated in Magna Graecia largely during the 4th century BC. The settlers of Magna Graecia had great successes in the Ancient Olympic Games in their homeland. Crotone's athletes won 18 titles in 25 Olympics.[8] Although many of the Greek inhabitants of Magna Graecia were entirely Latinized during the Middle Ages,[9] pockets of Greek culture and language remained and have survived to the present day. One example is the Griko people in Calabria (Bovesia) and Salento (Grecìa Salentina), some of whom still maintain their Greek language (Griko language) and customs.[10] The Griko language is the last living trace of the Greek elements that once formed Magna Graecia.[11]

Terminology[edit]

The original Greek expression Megálē Hellás (lit. 'Great[er] Greece'), later translated into Latin as Magna Graecia, is attested for the first time in a passage from the 2nd century BC by the Greek historian Polybius[12] (written around 150 BC), where he ascribed the term to Pythagoras and his philosophical school.[13][14]

Ancient authors use "Magna Graecia" to mean different parts of southern Italy,[15][16][17] including or excluding Sicily, Strabo and Livy being the most prominent advocates of the wider definitions.[18] Strabo used the term to refer to the territory that had been conquered by the Greeks.[19][20]

There are various hypotheses on the origin of the name Megálē Hellás. The term could be explained by the prosperity and cultural and economic splendour of the region (6th–5th century BC); notably by the Achaeans of the city of Kroton, to refer to the network of colonies they founded or controlled between the end of the 6th and mid-5th centuries at the time of the Pythagoreans.[21]

Context[edit]

There were several reasons for the Greeks to establish overseas colonies; demographic crises (famine, overcrowding, etc.), stasis, a developing need for new commercial outlets and ports, and expulsion from their homeland after wars.

During the Archaic period, the Greek population grew beyond the capacity of the limited arable land of Greece proper, resulting in the large-scale establishment of colonies elsewhere: according to one estimate, the population of the widening area of Greek settlement increased roughly tenfold from 800 BC to 400 BC, from 800,000 to as many as 7+1⁄2-10 million.[22] This was not simply for trade, but also to found settlements. These Greek colonies were not, as Roman colonies were, dependent on their mother-city, but were independent city-states in their own right.[23]

Another reason was the strong economic growth with the consequent overpopulation of the motherland.[5] The terrain that some of these Greek city-states were in could not support a large city. Politics was also the reason as refugees from Greek city-states tended to settle away from these cities in the colonies.[24]

Greeks settled outside of Greece in two distinct ways. The first was in permanent settlements founded by the Greeks, which formed as independent poleis. The second form was in what historians refer to as emporia; trading posts which were occupied by both Greeks and non-Greeks and which were primarily concerned with the manufacture and sale of goods. Examples of this latter type of settlement are found at Al Mina in the east and Pithekoussai in the west.[25]

From about 750 BC the Greeks began 250 years of expansion, settling colonies in all directions.

History[edit]

Greek colonisation[edit]

According to Strabo's Geographica, the colonisation of Magna Graecia had already begun by the time of the Trojan War and lasted for several centuries.[26]

Greeks began to settle in southern Italy in the 8th century BC.[20] Their first great migratory wave was by the Euboeans aimed at the Gulf of Naples (Pithecusae, Cumae) and the Strait of Messina (Zancle, Rhegium).[27] Pithecusae on the island of Ischia is considered the oldest Greek settlement in Italy, and Cumae their first colony on the mainland of Italy.

The second wave was of the Achaeans who concentrated initially on the Ionian coast (Metapontion, Poseidonia, Sybaris, Kroton),[28][29] shortly before 720 BC.[30] At an unknown date between the 8th and 6th centuries BC the Athenians, of Ionian lineage, founded Scylletium (near today's Catanzaro).[31]

With colonisation, Greek culture was exported to Italy with its dialects of the Ancient Greek language, its religious rites, and its traditions of the independent polis. An original Hellenic civilization soon developed, and later interacted with the native Italic civilisations. The most important cultural transplant was the Chalcidean/Cumaean variety of the Greek alphabet, which was adopted by the Etruscans; the Old Italic alphabet subsequently evolved into the Latin alphabet, which became the most widely used alphabet in the world.

Secondary colonisation[edit]

Over time, due to overpopulation and other political and commercial reasons, the new cities expanded their presence in Italy by founding other Greek cities; effectively expanding the Greek civilisation to the whole territory known today as Magna Graecia.[30]

Remains of some of these Greek colonies can be seen today such as those of Neapolis ('new city', now Naples), Syracusae (Syracuse), Akragas (Agrigento), Taras (Taranto) and Rhegion (Reggio Calabria).

An intense colonisation program was undertaken by Syracuse,[32] at the time of the tyranny of Dionysius I of Syracuse, around 387–385 BC. This phenomenon affected the entire Adriatic coast, and in particular led to the foundation in Italy of Ancon (now Ancona) and Adria; in the Dalmatian coast he saw the foundation of Issa (current Vis), Pharus (Stari Grad), Dimus (Hvar); Lissus (now Lezhë) was founded on the Albanian coast. Issa in turn then founded Tragurium (now Trogir), Corcyra Melaina (now Korčula) and Epetium (now Stobreč, a suburb of Split).

Rhegium (now Reggio Calabria) founded Pyxus (Policastro Bussentino) in Lucania; Locri founded Medma (Rosarno), Polyxena and Hipponium (Vibo Valentia) in present-day Calabria; Sybaris (now Sibari) revitalised the indigenous centres of Laüs and Scydrus in Calabria and founded Poseidonia (Paestum), in Campania; Kroton (now Crotone) founded Terina and participated in the foundation of Caulonia (near Monasterace marina) in Calabria; Messana (now Messina), in collaboration with Rhegium, founded Metaurus (Gioia Tauro); Taras together with Thurii founded Heracleia (Policoro) in Lucania in 434 BC, and also Callipolis ('beautiful city').[33]

Expansion and conflict[edit]

At the beginning of the 6th century, all the main cities of Magna Graecia on the Ionian Sea had achieved a high economic and cultural development, which shifted their interests towards expansion of their territory by waging war on neighbouring cities. The 6th century was therefore characterised by great clashes between the colonies. Some of the clashes that established the new balance and the new relationships of force were the Battle of the Sagra river (the clash between Locri Epizefiri and Kroton), the destruction of Siris (by Sybaris and Metapontum), and the clash between Kroton and Sybaris (which ended with the destruction of the latter).[34]

As with all the events of this period precise dates are unknown, but the destruction of Sybaris may have occurred around 510 BC, while the two other clashes are placed around 580-560 BC, with the destruction of Siris before the Battle of the Sagra.

Roman Era[edit]

The first Greek city to be absorbed into the Roman Republic was Neàpolis in 327 BC.[35]

At the beginning of the 3rd century, Rome was a great power but had not yet entered into conflict with most of Magna Graecia, which had been allies of the Samnites. However, the needs of the Roman populace determined their need for territorial expansion towards the south.[36] As the Greek cities of southern Italy came under threat from the Bruttii and Lucanians from the end of the 4th century BC, they asked for help from Rome, which exploited this opportunity by sending military garrisons in the 280s BC.[37]

Following Rome's victory over Taras after the Pyrrhic War in 272 BC, most of the cities of southern Italy were linked to Rome with pacts and treaties (foedera) which sanctioned a sort of indirect control.[38]

Sicily was conquered by Rome during the First Punic War. Only Syracuse remained independent until 212 because its king Hiero II was a devoted ally of the Romans. His grandson Hieronymus however allied with Hannibal, which prompted the Romans to besiege the city, which fell in 212 BC.

After the second Punic War, Rome pursued an unprecedented program of reorganisation in the rest of Magna Graecia, where many of the cities were annexed to the Roman Republic in 205 BC, as a consequence of their defection to Hannibal.[7] Roman colonies (civium romanorum) were the main element of the new territorial control plan starting from the lex Atinia of 197 BC. In 194 BC, garrisons of 300 Roman veterans were implanted in Volturnum, Liternum, Puteoli, Salernum and Buxentum, and to Sipontum on the Adriatic. This model was replicated in the territory of the Brettii; 194 BC saw the foundation of the Roman colonies of Kroton and Tempsa, followed by the Latin colonies of Copia (193 BC) and Valentia (192 BC).[39]

The social, linguistic and administrative changes arising from the Roman conquest only took root in this region by the 1st century AD, while Greek culture remained strong and was actively cultivated as shown by epigraphic evidence.[40]

Middle Ages[edit]

During the Early Middle Ages, following the disastrous Gothic War, new waves of Byzantine Christian Greeks fleeing the Slavic invasion of Peloponnese settled in Calabria, further strengthened the Hellenic element in the region.[41] The iconoclast emperor Leo III appropriated lands that had been granted to the Papacy in southern Italy and the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire continued to govern the area in the form of the Catapanate of Italy (965 -1071) through the Middle Ages, well after northern Italy fell to the Lombards.[42]

At the time of the Normans' late medieval conquest of southern Italy and Sicily (in the late 12th century), the Salento peninsula (the "heel" of Italy), up to one-third of Sicily (concentrated in the Val Demone), and much of Calabria and Lucania were still largely Greek-speaking. Some regions of southern Italy experienced demographic shifts as Greeks began to migrate northwards in significant numbers from regions further south; one such region was Cilento, which came to have a Greek-speaking majority.[43][44][45] At this time the language had evolved into medieval Greek, also known as Byzantine Greek, and its speakers were known as Byzantine Greeks. The resultant fusion of local Byzantine Greek culture with Norman and Arab culture (from the Arab occupation of Sicily) gave rise to Norman-Arab-Byzantine culture in Sicily.

-

The goddess Nike riding on a two-horse chariot, Apulian patera (tray), 4th century BC, Archaeological Museum of Milan

-

Head-Kantharos of a Female Faun or Io, red-figure pottery, 75-350 BC, Los Angeles County Museum of Art

List of Greek poleis[edit]

Mainland Italy[edit]

This is a list of the 22 poleis ("city-states") in Italy, according to Mogens Herman Hansen.[46] It does not list all the Hellenic settlements, only those organised around a polis structure.

| Ancient name(s) | Location | Modern name(s) | Foundation date | Mother city | Founder(s) |

| Herakleia (Lucania) | Basilicata | (abandoned) | 433–432 BC | Taras (and Thourioi) | Unknown |

| Hipponion | Calabria | Vibo Valentia | late 7th century BC | Lokroi Epizephiroi | Unknown |

| Hyele, or Elea, Velia (Roman name) | Campania | (abandoned) | c.540–535 BC | Phokaia, Massalia | Refugees from Alalie |

| Kaulonia | Calabria | (abandoned) | 7th century BC | Kroton | Typhon of Aigion |

| Kroton | Calabria | Crotone | 709–708 BC | Rhypes, Achaia | Myscellus |

| Kyme, Cumae (Roman name) | Campania | (abandoned) | c.750–725 BC | Chalkis and Eretria | Hippokles of Euboian Kyme and Megasthenes of Chalkis |

| Laos | Calabria | (abandoned) | before 510 BC | Sybaris | Refugees from Sybaris |

| Lokroi (Epizephiroi) | Calabria | Locri | early 7th century BC | Lokris | Unknown |

| Medma | Calabria | (abandoned) | 7th century BC | Lokroi Epizephiroi | Unknown |

| Metapontion | Basilicata | Metaponto | c. 630 BC | Achaia | Leukippos of Achaia |

| Metauros | Calabria | Gioia Tauro | 7th century BC | Zankle (or possibly Lokroi Epizephiroi) | Unknown |

| Neàpolis | Campania | Naples | 6th–5th centuries BC (previously an 8th century BC harbour of Kyme known as Parthenope) | Kyme | Unknown |

| Pithekoussai | Campania | Ischia | 8th century BC | Chalkis and Eretria | Unknown |

| Poseidonia, Paestum (Roman name) | Campania | (abandoned) | c. 600 BC | Sybaris (and perhaps Troizen) | Unknown |

| Pyxous | Campania | Policastro Bussentino | 471–470 BC | Rhegion and Messena | Mikythos, tyrant of Rhegion and Messena |

| Rhegion | Calabria | Reggio Calabria | 8th century BC | Chalkis (with Zankle and Messenian refugees) | Antimnestos of Zankle (or perhaps Artimedes of Chalkis) |

| Siris | Basilicata | (abandoned) | c. 660 BC (or c. 700 BC) | Kolophon | Refugees from Kolophon |

| Sybaris | Calabria | Sibari | 721–720 (or 709–708) BC | Achaia and Troizen | Is of Helike |

| Taras | Apulia | Taranto | c. 706 BC | Sparta | Phalanthos and the Partheniai |

| Temesa | unknown, but in Calabria | (abandoned) | no Greek founder (Ausones who became Hellenised) | ||

| Terina | Calabria | (abandoned) | before 460 BC, perhaps c. 510 BC | Kroton | Unknown |

| Thourioi | Calabria | (abandoned) | 446 and 444–443 BC | Athens and many other cities | Lampon and Xenokrates of Athens |

Sicily[edit]

This is a list of the 46 poleis ("city-states") in Sicily, according to Mogens Herman Hansen.[47] It does not list all the Hellenic settlements, only those organised around a polis structure.

| Ancient name(s) | Location | Modern name(s) | Foundation date | Mother city | Founder(s) |

| Abakainon | Metropolitan City of Messina | (abandoned) | no Greek founder (Sicels who became Hellenised) | ||

| Adranon | Metropolitan City of Catania | Adrano | c.400 BC | Syrakousai | Dionysios I |

| Agyrion | Province of Enna | Agira | no Greek founder (Sicels who became Hellenised) | ||

| Aitna | Metropolitan City of Catania | on the site of Katane | 476 BC | Syrakousai | Hieron |

| Akragas | Province of Agrigento | Agrigento | c.580 BC | Gela | Aristonoos and Pystilos |

| Akrai | Province of Syracuse | near Palazzolo Acreide | 664 BC | Syrakousai | Unknown |

| Alaisa | Metropolitan City of Messina | Tusa | 403–402 BC | Herbita | Archonides of Herbita |

| Alontion, Haluntium (Roman name) | Metropolitan City of Messina | San Marco d'Alunzio | no Greek founder (Sicels who became Hellenised) | ||

| Apollonia | Metropolitan City of Messina | Monte Vecchio near San Fratello | 405–367 BC | Syrakousai | Possibly Dionysios I |

| Engyon | Province of Enna | Troina? | no Greek founder (Sicels who became Hellenised) | ||

| Euboia | Metropolitan City of Catania | Licodia Eubea | 7th century BC, perhaps late 8th century BC | Leontinoi | Unknown |

| Galeria | Unknown | (abandoned) | no Greek founder (Sicels who became Hellenised) | ||

| Gela | Province of Caltanissetta | Gela | 689–688 BC | Rhodes (Lindos), Cretans | Antiphemos of Rhodes and Entimos the Cretan |

| Heloron | Province of Syracuse | (abandoned) | Unknown | Syrakousai | Unknown |

| Henna | Province of Enna | Enna | no Greek founder (Sicels who became Hellenised) | ||

| Herakleia Minoa | Province of Agrigento | Cattolica Eraclea | after 628 BC | Selinous, Sparta | refounded by Euryleon after c.510 BC |

| Herakleia | unlocated in Western Sicily | (abandoned) | c.510 BC | Sparta | Dorieus |

| Herbessos | Province of Enna | Montagna di Marzo | no Greek founder (Sicels who became Hellenised) | ||

| Herbita | Unknown | (abandoned) | no Greek founder (Sicels who became Hellenised) | ||

| Himera | Province of Palermo | Termini Imerese | 648 BC | Zankle, exiles from Syrakousai | Eukleides, Simos and Sakon |

| Hippana | Province of Palermo | Monte dei Cavalli | no Greek founder (indigenous settlement that became Hellenised) | ||

| Imachara | Metropolitan City of Catania | Mendolito | no Greek founder (Sicels who became Hellenised) | ||

| Kallipolis | Unknown | (abandoned) | late 8th century BC | Naxos (Sicily) | Unknown |

| Kamarina | Province of Ragusa | Santa Croce Camerina | c.598 BC | Syrakousai, Korinth | Daskon of Syracuse and Menekolos of Corinth |

| Kasmenai | Province of Syracuse | (abandoned) | 644–643 BC | Syrakousai | Unknown |

| Katane | Metropolitan City of Catania | Catania | 729 BC | Naxos (Sicily) | Euarchos |

| Kentoripa | Province of Enna | Centuripe | no Greek founder (Sicels who became Hellenised) | ||

| Kephaloidion | Province of Palermo | Cefalù | no Greek founder (Sicels who became Hellenised) | ||

| Leontinoi | Province of Syracuse | Lentini | 729 BC | Naxos (Sicily) | Theokles? |

| Lipara | Metropolitan City of Messina | Lipari | 580–576 BC | Knidos, Rhodes | Pentathlos, Gorgos, Thestor and Epithersides |

| Longane | Metropolitan City of Messina | near Rodì Milici | no Greek founder (Sicels who became Hellenised) | ||

| Megara Hyblaea | Province of Syracuse | Augusta | 728 BC | Megara Nisaia | Theokles? |

| Morgantina | Province of Enna | near Aidone | no Greek founder (Sicels who became Hellenised) | ||

| Mylai | Metropolitan City of Messina | Milazzo | 700 BC? | Zankle | Unknown |

| Nakone | Unknown | (abandoned) | no Greek founder (Sicels who became Hellenised) | ||

| Naxos | Metropolitan City of Messina | Giardini Naxos | 735–734 BC | Chalkis, Naxos (Cyclades) | Theokles |

| Petra | Unknown | (abandoned) | no Greek founder (indigenous settlement that became Hellenised) | ||

| Piakos | Metropolitan City of Catania | Mendolito? | no Greek founder (Sicels who became Hellenised) | ||

| Selinous | Province of Trapani | Marinella di Selinunte | 628–627 BC | Megara Hyblaea | Pammilos |

| Sileraioi | Unknown | (abandoned) | no Greek founder (indigenous settlement that became Hellenised) | ||

| Stielanaioi | Metropolitan City of Catania? | (abandoned) | no Greek founder (indigenous settlement that became Hellenised) | ||

| Syrakousai | Province of Syracuse | Syracuse | 733 BC | Korinth | Archias of Korinth |

| Tauromenion | Metropolitan City of Catania | Taormina | 392 BC | Syrakousai | perhaps Dionysios I |

| Tyndaris | Metropolitan City of Messina | Tindari | 396 BC | Syrakousai | Dionysios I |

| Tyrrhenoi | Province of Palermo? | Alimena? | no Greek founder (indigenous settlement that became Hellenised) | ||

| Zankle/Messana | Metropolitan City of Messina | Messina | c.730 | Chalkis, Kyme | Perieres of Kyme and Krataimenes of Chalkis |

Not part of Magna Graecia[edit]

| Ancient name(s) | Location | Modern name(s) | Foundation date | Mother city | Founder(s) |

| Adrìa | Veneto | Adria | 385 BC | Syrakousai | Unknown |

| Ankón | Marche | Ancona | 387 BC | Syrakousai | Unknown |

Administration[edit]

The administrative organisation of Magna Graecia was inherited from the Hellenic poleis, taking up the concept of "city-states" administered by the aristocracy.[5] The cities of Magna Graecia were independent like the Greek poleis of the motherland,[48] and had an army and a military fleet.[49][50][51] There were also cases of tyranny as in Syracuse, governed by the tyrant Dionysius, who fought the Carthaginians until his death.[48][52]

Economy[edit]

In the cities of Magna Graecia, trade, agriculture and crafts developed. Initially oriented to the indigenous Italic populations, the trade was immediately an excellent channel of exchange with the Greeks of the motherland, even if today it is difficult to establish precisely the type of goods traded and the volume of these exchanges.[30]

Coinage[edit]

Greek coinage of Italy and Sicily originated from local Italiotes and Siceliotes who formed numerous city-states. These Hellenistic communities descended from Greek migrants. Southern Italy was so thoroughly Hellenized that it was known as the Magna Graecia. Each of the polities struck their own coinage.

Taras (or Tarentum) was among the most prominent city-states.

By the second century BC, some of these Greek coinages evolved under Roman rule, and can be classified as the first Roman provincial currencies.

Culture[edit]

The Greek colonists of Magna Graecia elaborated a civilization of the highest level,[3] which had peculiar characteristics, due to the distance from the motherland and the influence of the indigenous peoples of southern Italy.[3] From the motherland Greece, art, literature and philosophy decisively influenced the life of the colonies. In Magna Graecia much impetus was given to culture, especially in some cities, such as Taras (now Taranto).[5] Pythagoras moved to Crotone where he founded his school in 530 BC. Among others, Aeschylus, Herodotus, Xenophanes and Plato visited Magna Graecia.

Among the illustrious characters born in Magna Graecia are the philosophers Parmenides of Elea, Zeno of Elea, Gorgias of Lentini and Empedocles of Agrigento; the Pythagoreans Philolaus of Crotone, Archytas of Taranto, Lysis of Taranto, Echecrates and Timaeus of Locri; the mathematician Archimedes of Syracuse; the poets Theocritus of Syracuse, Stesichorus, Ibycus of Reggio Calabria, Nossis of Locri, Alexis of Thuri and Leonidas of Taranto; the doctors Alcmeon of Crotone and Democedes of Crotone; the sculptor from Reggio Clearchus; the painter Zeuxis, the musicologist Aristoxenus of Taranto and the legislator Zaleucus of Locri.

Language[edit]

A remnant of Greek influence can be found in the survival of the Greek language in some villages of the above-mentioned Salento peninsula (the "heel" of Italy). This living dialect of Greek, known locally as Griko, is found in the Italian regions of Calabria and Apulia. Griko is considered by linguists to be a descendant of Byzantine Greek, which had been the majority language of Salento through the Middle Ages, combining also some ancient Doric and local romance elements. There is a rich oral tradition and Griko folklore, limited now but once numerous, to around 30,000 people, most of them having abandoned their language in favour of Italian. Some scholars, such as Gerhard Rohlfs, argue that the origins of Griko may ultimately be traced to the colonies of Magna Graecia.[53]

Art and architecture[edit]

Magna Graecia, in some fields such as architecture and urban planning, sometimes surpassed the mother country and the other Greek colonies.[4] In Magna Graecia, as well as in the other Greek colonies, the Doric style enriched with showy decorations was adopted as the dominant architectural style. In Magna Graecia, in particular, a Doric style influenced by the Ionic one was also used, especially in Sicily in the Achaean colonies.[4] In Magna Graecia, limestone was used as a building material due to the difficulty in finding other materials. The Doric style in Magna Graecia reached its apogee, surpassing that of the motherland and the other Greek colonies.[4]

Regarding urban planning, the cities of Magna Graecia, as well as many cities of Greek colonies in other regions, were more orderly and rational in the distribution of spaces than those of the mother country, making the urban fabric more practical. The first examples of urbanistically more rational Greek cities belonged to Magna Graecia, in this case Taranto, Metapontum and Megara Hyblaea.[4] Characteristic of this new urban concept, which later spread also in the motherland to Rhodes and Miletus, was a checkerboard road network.[4]

In Magna Graecia painting and sculpture also reached a notable level of quality.[54][55] In Magna Graecia there were examples of excellence in sculpture, coroplastics and bronzes.[54] As for vase painting, many famous Athenian potters moved to Magna Graecia creating works influenced by the culture of the place, making their paintings peculiar and different from those of the motherland,[55] giving rise to the South Italian ancient Greek pottery. Also noteworthy are the mosaics, the goldsmith's art and wall painting.[56][57]

Noteworthy sculptures from Magna Graecia are the Apollo of Gaza, the Apollo of Piombino, the Dancing Satyr of Mazara del Vallo, the Head of a Philosopher and the Riace bronzes, while notable vases from Magna Graecia are the Darius Vase and the Nestor's Cup. Noteworthy temples of Magna Graecia are the Temple of Concordia, Agrigento, the Temple of Hera Lacinia, the Temple of Heracles, Agrigento, The Temple of Juno in Agrigento, the Temple of Olympian Zeus, Agrigento, the Temple of Apollo (Syracuse), the Temple of Athena (Syracuse), the Temple of Athena (Paestum), the Temple C (Selinus), the Temple E (Selinus), the Temple F (Selinus), the Temple of Juno Lacinia (Crotone), the Second Temple of Hera (Paestum), the Heraion at Foce del Sele, the Temple of Poseidon (Taranto), the Tavole Palatine and the Temple of Victory (Himera).

Theatre[edit]

The Sicilian Greek colonists in Magna Graecia, but also from Campania and Apulia, also brought theatrical art from their motherland.[58] The Greek Theatre of Syracuse, the Greek Theatre of Segesta, the Greek Theatre of Tindari, the Greek Theatre of Hippana, the Greek Theatre of Akrai, the Greek Theatre of Monte Jato, the Greek Theatre of Morgantina and the most famous Greek Theater of Taormina, amply demonstrate this.

Only fragments of original dramaturgical works are left, but the tragedies of the three great giants Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides and the comedies of Aristophanes are known.[59]

Some famous playwrights in the Greek language came directly from Magna Graecia. Others, such as Aeschylus and Epicharmus, worked for a long time in Sicily. Epicharmus can be considered Syracusan in all respects, having worked all his life with the tyrants of Syracuse. His comedy preceded that of the more famous Aristophanes by staging the gods for the first time in comedy. While Aeschylus, after a long stay in the Sicilian colonies, died in Sicily in the colony of Gela in 456 BC. Epicarmus and Phormis, both of 6th century BC, are the basis, for Aristotle, of the invention of the Greek comedy, as he says in his book on Poetics:[60]

As for the composition of the stories (Epicharmus and Phormis) it came in the beginning from Sicily

— Aristotle, Poetics

Other native dramatic authors of Magna Graecia, in addition to the Syracusan Phormis mentioned, are Achaeus of Syracuse, Apollodorus of Gela, Philemon of Syracuse and his son Philemon the younger. From Calabria, precisely from the colony of Thurii, came the playwright Alexis. While Rhinthon, although Sicilian from Syracuse, worked almost exclusively for the colony of Taranto.[61]

Sport[edit]

The colonies sent athletes of all disciplines to the Ancient Olympic Games which were periodically held at Olympia and Delphi in Greece.[8]

The colonists of Magna Graecia were very fond of the Hellenic games where they could prove to the Greeks that they belonged to the same place of origin, their physical strength and skills in the games were also played by their ancestors dozens of generations earlier. And for this reason the greatest sovereigns demanded that teams be trained to be sent to Greece.[62]

Sport was therefore a channel of communication with the Hellenic peninsula, a means by which the colonies of Magna Graecia showed themselves to the rest of the Hellenic world. The settlers of Magna Graecia had great success in sporting competitions in their homeland. Crotone's athletes won 18 titles in 25 Olympics.[8]

Essential timeline[edit]

| History of Italy |

|---|

|

|

|

- 8th century BC: the first historical colony of Magna Graecia was that of Pithekoussai (current island of Ischia) founded in the 8th century BC by settlers from Chalcis and Eretria in Euboea. Probably, the island settlement of Pithekoussai was only a commercial establishment where the Greeks dealt with other peoples, especially with the Phoenician merchants, even if the issue is controversial.[63]

- 720 BC: the first Greek colony in mainland Italy, Kyme, is founded.[64]

- 7th–6th century BC: maximum splendor of Sibari.[30]

- 6th century BC: maximum splendor of Crotone.[5]

- 6th–3rd century BC: minting of coins by the cities of Magna Graecia.[21]

- 6th–5th century BC: maximum splendour of Magna Graecia due to the Pythagorean reforms and institutions.[30]

- 510 BC: Sibari was defeated by Crotone whose troops were commanded by the famous athlete Milo of Croton. The city of Sibari was destroyed and its population was condemned to exile.[65]

- 5th century BC: maximum splendor of Syracuse.[5]

- 480 BC: Gelon, tyrant of Syracuse, defeated the troops of Carthage at Himera, in the north of Sicily.

- 474 BC: The fleet led by Hiero I, tyrant of Syracuse, assisted Kyme threatened by the Etruscans. This victory marked the end of the Etruscan extension in Campania.[66]

- 459–454 BC: after an internal civil war in Crotone, the cities of Magna Graecia once linked to it, dissolve the bond of subjection.[30]

- 444–443 BC: foundation of Thourioi. An Athenian expedition, officially Panhellenic because it was made up of Greeks from the islands of the Aegean Sea, founded the city of Thourioi. In reality, the cities of the Aegean Sea were part of the Delian League, a military league under the rule of Athens. The city of Thourioi hosted important people such as Herodotus, Protagoras, Hippodamus of Miletus and Lysias.[67]

- 415–413 BC: The Sicilian Expedition occurred. It was an Athenian military expedition to Sicily, which took place from 415 to 413 BC, during the Peloponnesian War, between Athens on one side and Sparta, Syracuse and Corinth on the other. The expedition ended in a devastating defeat for the Athenian forces, severely impacting Athens. After the first Athenian victories, which put the Syracusan army in serious difficulty, the tide of the war was turned upside-down due to the Spartan reinforcements under the command of Gylippus. The defeat of the Athenian army led to the imprisonment of its soldiers in the Syracusan latomies, where they were forced to live in hardship and suffering until their death; few were the survivors who managed to return to their homeland. The failure of the expedition marked the beginning of the military and political decline of Athens, followed by the aristocratic coup d'état of 411 BC; it also marked Athens' definitive defeat in the Peloponnesian War (404 BC). Thucydides, an Athenian historian, dedicates two books of his work History of the Peloponnesian War to the Athenian expedition, to underline the magnitude and exceptionality of the event.[68] Thus he began "a new work, a work on Sicily"[69] which became the background of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC). The Parallel Lives of Plutarch (in particular the Life of Nicias) and the Bibliotheca historica of Diodorus Siculus are other important sources on the expedition to Sicily.[70]

- 400 BC: the cities of Magna Graecia overlooking the Tyrrhenian Sea begin at the hands of the Italic peoples.[30]

- 4th century BC: the cultural decline of the cities of Magna Graecia begins.[30]

- 387 BC: Reggio is destroyed by Syracuse.[30]

- 303 BC: peace between Taranto and Lucanians, who had attempted to conquer the city.[30]

- 285 BC: Roman garrisons settle in Thourioi.[30]

- 282–272 BC: Taranto was conquered by the Romans despite the intervention of Pyrrhus (Pyrrhic War in Italy).

- 264–241 BC: First Punic War, Rome takes control of Sicily, with the exception of Syracuse, which becomes Rome's ally.

- 215–205 BC: during the Second Punic War Syracuse and then Taranto sided with Carthage. The two cities were conquered by the Romans in 211 after a three-year siege. These events put an end to the independence of all the cities of Magna Graecia, which were annexed to the Roman Republic in 205 BC.[7]

Modern and contemporary Italy[edit]

Greek nobles started taking refuge in Italy following the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.[71] Greeks immigrated once again to the region in the 16th and 17th centuries in reaction to the conquest of the Peloponnese by the Ottoman Empire. Especially after the end of the Siege of Coron (1534), large numbers of Greeks took refuge in the areas of Calabria, Salento and Sicily. Greeks from Coroni, the so-called Coronians, were nobles, who brought with them substantial movable property.[72]

Other Greeks who moved to Italy came from the Mani Peninsula of the Peloponnese. The Maniots (their name originating from the Greek word mania)[73] were known for their proud military traditions and for their bloody vendettas, many of which continue today.[74] Another group of Maniot Greeks moved to Corsica in the 17th century under the protection of the Republic of Genoa.[75]

Although many of the Greek inhabitants of Magna Graecia were entirely Latinized during the Middle Ages,[9] pockets of Greek culture and language remained and have survived to the present day. One example is the Griko people in Calabria (Bovesia) and Salento (Grecìa Salentina), some of whom still maintain their Greek language (Griko language) and customs.[10] The Griko language is the last living trace of the Greek elements that once formed Magna Graecia.[11] Their working practices have been passed down through generations through storytelling and allowing the observation of work.[76] The Italian parliament recognizes the Griko people as an ethnolinguistic minority under the official name of Minoranze linguistiche Grike dell'Etnia Griko-Calabrese e Salentina.[77]

Messina in Sicily is home to a small Greek-speaking minority, which arrived from the Peloponnese between 1533 and 1534 when fleeing the expansion of the Ottoman Empire. They were officially recognised in 2012.[78]

[edit]

Valle dei Templi[edit]

The Valle dei Templi, or Valley of the Temples, is an archaeological site in Agrigento (ancient Greek Akragas), Sicily. It is one of the most outstanding examples of ancient Greek art and architecture of Magna Graecia.[79] The term "valley" is a misnomer, the site is located on a ridge outside the town of Agrigento.

Since 1997, the entire area has been included in the UNESCO World Heritage List. The archaeological and landscape park of the Valle dei Templi, with its 1,300 hectares, is the largest archaeological park in Europe and the Mediterranean basin.[80]

The Valley includes remains of seven temples, all in Doric style. The ascription of the names, apart from that of the Olympeion, is a mere tradition established in Renaissance times. The temples are:

- Temple of Concordia, whose name comes from a Latin inscription found nearby, and which was built in the 5th century BC. Turned into a church in the 6th century AD, it is now one of the best preserved in the Valley.

- Temple of Juno, also built in the 5th century BC. It was burnt in 406 BC by the Carthaginians.

- Temple of Heracles, who was one of the most venerated deities in the ancient Akragas. It is the most ancient in the Valley: destroyed by an earthquake, it consists today of only eight columns.

- Temple of Olympian Zeus, built in 480 BC to celebrate the city-state's victory over Carthage. It is characterized by the use of large-scale atlases.

- Temple of Castor and Pollux. Despite its remains including only four columns, it is now the symbol of modern Agrigento.

- Temple of Hephaestus (Vulcan), also dating from the 5th century BC. It is thought to have been one of the most imposing constructions in the valley; it is now however one of the most eroded.

- Temple of Asclepius, located far from the ancient town's walls; it was the goal of pilgrims seeking cures for illness.

The Valley is also home to the so-called Tomb of Theron, a large tuff monument of pyramidal shape; scholars suppose it was built to commemorate the Romans killed in the Second Punic War.

Poseidonia and Elea[edit]

Cilento, Vallo di Diano and Alburni National Park (Italian Parco Nazionale del Cilento, Vallo di Diano e Alburni) is an Italian national park in the Province of Salerno, in Campania in southern Italy. It includes much of the Cilento, the Vallo di Diano and the Monti Alburni. It was founded in 1991, and was formerly known as the Parco Nazionale del Cilento e Vallo di Diano. In 1998 it became a World Heritage Site of UNESCO,[81] along with the ancient Greek towns of Poseidonia, Elea and the Padula[b] Charterhouse.

Much of the most celebrated features of the Poseidonia site today are the three large temples in the Archaic version of the Greek Doric order, dating from about 550 to 450 BC. All are typical of the period,[c] with massive colonnades having a very pronounced entasis (widening as they go down), and very wide capitals resembling upturned mushrooms. Above the columns, only the second Temple of Hera retains most of its entablature, the other two having only the architrave in place. These were dedicated to Hera and Athena (Juno and Minerva to the Romans), although previously they often have been identified otherwise, following eighteenth-century arguments. The two temples of Hera are right next to each other, while the Temple of Athena is on the other side of the town centre. There were other temples, both Greek and Roman, which are far less well preserved.

Remains of Elea walls, with traces of one gate and several towers, of a total length of over three miles, still exist, and belong to three different periods, in all of which the crystalline limestone of the locality is used. Bricks were also employed in later times; their form is peculiar to this place, each having two rectangular channels on one side, and being about 1.5 inches square, with a thickness of nearly 4 inches They all bear Greek brick-stamps. There are some remains of cisterns on the site, and, various other traces of buildings.[82]

Syracuse[edit]

Syracuse was founded in 733 BC by Greek settlers from Corinth and Tenea, led by the oecist (colonizer) Archias. There are many attested variants of the name of the city including Συράκουσαι Syrakousai, Συράκοσαι Syrakosai and Συρακώ Syrakō. In the modern day, the city is listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site along with the Necropolis of Pantalica.

The buildings of Syracuse from the Greek period are:

- The city walls

- The Temple of Apollo, at Piazza Emanuele Pancali, adapted to a church in Byzantine times and to a mosque under Arab rule.

- The Fountain of Arethusa, on Ortygia island. According to a legend, the nymph Arethusa, hunted by Alpheus, was turned into a spring by Artemis and appeared here.[83]

- The Greek Theatre of Syracuse, whose cavea is one of the largest ever built by the ancient Greeks: it has 67 rows, divided into nine sections with eight aisles. Only traces of the scene and the orchestra remain. The edifice (still used today) was modified by the Romans, who adapted it to their different style of spectacles, including circus games. Near the theatre are the latomìe, stone quarries, also used as prisons in ancient times. The most famous latomìa is the Orecchio di Dionisio ("Ear of Dionysius").

- The Tomb of Archimede, in the Grotticelli Necropolis. Decorated with two Doric columns.

- The Temple of Olympian Zeus, about 3 kilometres (2 miles) outside the city, built around the 6th century BC.

[edit]

Apulia[edit]

Basilicata[edit]

Calabria[edit]

Campania[edit]

Sicily[edit]

- Abacaenum

- Adranon

- Aetna

- Akrai

- Akrillai

- Apollonia

- Casmenae

- Eryx

- Halaesa

- Helorus

- Heraclea Minoa

- Herbessos

- Himera

- Hybla Gereatis

- Maktorion

- Megara Hyblaea

- Monte Adranone

- Morgantina

- Motya

- Naxos

- Segesta

- Selinunte

- Tindari

- Valle dei Templi

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ UK: /ˌmæɡnə ˈɡriːsiə, - ˈɡriːʃə/ MAG-nə GREE-see-ə, - GREE-shə, US: /- ˈɡreɪʃə/ - GRAY-shə, Latin: [ˈmaŋna ˈɡrae̯ki.a]; lit. 'Great[er] Greece'; Ancient Greek: Μεγάλη Ἑλλάς, romanized: Megálē Hellás, IPA: [meɡálɛː hellás], with the same meaning; Italian: Magna Grecia, IPA: [ˈmaɲɲa ˈɡrɛːtʃa].

- ^ Municipality not included in the park but part of Vallo di Diano region.

- ^ Indeed, they very often are used to illustrate the style in architectural books.

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Sybaris: la storia della più ricca città della Magna Grecia" (in Italian). Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Henry Fanshawe Tozer (30 October 2014). A History of Ancient Geography. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-108-07875-7.

- ^ a b c d "Magna Grecia", Dizionario enciclopedico italiano (in Italian), vol. VII, Treccani, 1970, p. 259

- ^ a b c d e f "L'architettura in Grecia e nelle colonie" (in Italian). Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Magna Grecia" (in Italian). Retrieved 9 July 2023.

- ^ Lazzarini, Mario (1995). La Magna Grecia (in Italian). Scorpione Editrice. p. 5. ISBN 88-8099-027-6.

- ^ a b c "Le arti di Efesto. Capolavori in metallo" (in Italian). p. 11. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ a b c "Olimpiadi antiche" (in Italian). Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Multilinguismo in Sicilia ea Napoli nel primo Medioevo" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ a b "Per la difesa e la valorizzazione della Lingua e Cultura Greco-Calabra" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ a b c "Una lingua, un'identità: alla scoperta del griko salentino" (in Italian). 25 May 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ Polybius, The Histories, II 39, 1-6-

- ^ Polybius, ii. 39.

- ^ A. J. Graham, "The colonial expansion of Greece", in John Boardman et al., Cambridge Ancient History, vol. III, part 3, p. 94.

- ^ Kathryn Lomas, Aspects of the Relationship between Rome and the Greek Cities of Southern Italy and Campania during the Republic and Early Empire, Thesis L3473, Newcastle University, 1989 http://theses.ncl.ac.uk/jspui/handle/10443/744 p. 9-10

- ^ Calderon, S. "La Conquista Romana di Magna Grecia. " ACTH 15,1975, 30-81

- ^ Justin 20.1

- ^ "MAGNA GRECIA" (in Italian). Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ Strabo 6.1.2

- ^ a b Luca Cerchiai; Lorena Jannelli; Fausto Longo (2004). The Greek Cities of Magna Graecia and Sicily. Getty Publications. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-89236-751-1.

- ^ a b "Magna Grecia nell'Enciclopedia Treccani" (in Italian). Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- ^ Population of the Greek city-states Archived 5 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Boardman & Hammond 1982, p. xiii

- ^ Descœudres, Jean-Paul (4 February 2013). "Greek colonization movement, 8th–6th centuries". The Encyclopedia of Global Human Migration. doi:10.1002/9781444351071.wbeghm260. ISBN 9781444334890.

- ^ Antonaccio 2007, p. 203

- ^ Strabo. "I, Section I". Geographica (in Greek). Vol. VI. Archived from the original on 22 May 2020. Retrieved 5 February 2020.

- ^ STEFANIA DE VIDO 'Capitani coraggiosi'. Gli Eubei nel Mediterraneo C. Bearzot, F. Landucci, in Tra il mare e il continente: l'isola d'Eubea (2013) ISBN 978-88-343-2634-3

- ^ Strabo 6.1.12

- ^ Herodotus 8.47

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "MAGNA GRECIA" (in Italian). Retrieved 7 July 2023.

- ^ Strabo, Geographica, 6.1.10

- ^ Braccesi, Lorenzo (1979). Grecità adriatica. Un capitolo della colonizzazione greca in Occidente (in Italian) (2nd ed.). Pàtron. p. 450. ISBN 978-88-555-0935-0.

- ^ "Gallipoli" (in Italian). Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- ^ Arte seconda - la colonizzazione e il periodo Greco, capitolo III, Il VI secolo e lo scontro con Crotone, Battaglia Della Sagra, https://www.locriantica.it/storia/per_greco3.htm

- ^ Heitland, William Emerton (1911). A Short History of the Roman Republic. The University Press. pp. 72.

Roman Republic Neapolis in 327 BC.

- ^ Musti, Domenico (1990). "La spinta verso il Sud: espansione romana e rapporti "internazionali"". Storia di Roma. Vol. I. P 536. Turin: Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-11741-2

- ^ DMITRIEV, S. (2017). The Status of Greek Cities in Roman Reception and Adaptation. Hermes, 145(2), 195–209. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26650396

- ^ Lane Fox, Robin (2005). The Classical World. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-102141-1. P 307

- ^ Giuseppe Celsi, La colonia romana di Croto e la statio di Lacenium, Gruppo Archeologico Krotoniate (GAK) https://www.gruppoarcheologicokr.it/la-colonia-romana-di-croto/

- ^ Kathryn Lomas, Aspects of the Relationship between Rome and the Greek Cities of Southern Italy and Campania during the Republic and Early Empire, Thesis L3473, Newcastle University, 1989 http://theses.ncl.ac.uk/jspui/handle/10443/744

- ^ "Slavs and nomadic populations in Greece". www2.rgzm.de. Archived from the original on 24 June 2021. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ^ Brown, T. S. (1979). "The Church of Ravenna and the Imperial Administration in the Seventh Century". The English Historical Review. 94 (370): 5. JSTOR 567155.

- ^ Loud, G. A. (2007). The Latin Church in Norman Italy. Cambridge University Press. p. 494. ISBN 978-0-521-25551-6.

At the end of the twelfth century ... While in Apulia Greeks were in a majority – and indeed present in any numbers at all – only in the Salento peninsula in the extreme south, at the time of the conquest they had an overwhelming preponderance in Lucania and central and southern Calabria, as well as comprising anything up to a third of the population of Sicily, concentrated especially in the north-east of the island, the Val Demone.

- ^ Oldfield, Paul (2014). Sanctity and Pilgrimage in Medieval Southern Italy, 1000–1200. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-107-00028-5.

However, the Byzantine revival of the tenth century generated a concomitant process Hellenization, while Muslim raids in southern Calabria, and instability in Sicily, may also have displaced Greek Christians further north on the mainland. Consequently, zones in northern Calabria, Lucania and central Apulia which were reintegrated into Byzantine control also experienced demographic shifts and the increasing establishment of immigrant Greek communities. These zones also acted as springboards for Greek migration further north, into regions such as the Cilento and areas around Salerno, which had never been under Byzantine control.

- ^ Kleinhenz, Christopher (2004). Medieval Italy: an encyclopedia, Volume 1. Routledge. pp. 444–445. ISBN 978-0-415-93930-0.

In Lucania (northern Calabria, Basilicata, and southernmost portion of today's Campania) ... From the late ninth century into the eleventh, Greek-speaking populations and Byzantine temporal power advanced, in stages but by no means always in tandem, out of southern Calabria and the lower Salentine peninsula across Lucania and through much of Apulia as well. By the early eleventh century, Greek settlement had radiated northward and had reached the interior of the Cilento, deep in Salernitan territory. Parts of the central and northwestern Salento, recovered early, [and] came to have a Greek majority through immigration, as did parts of Lucania.

- ^ Hansen & Nielsen (eds.), Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis, pp. 249–320.

- ^ Hansen & Nielsen (eds.), Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis, pp. 189–248.

- ^ a b "MAGNA GRECIA" (in Italian). Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories

- ^ "In Storia – ATENE E L'OCCIDENTE – Relazioni con le città siceliote ed italiote in funzione della spedizione in Sicilia – Parte I" (in Italian). Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Guerrazzi, Francesco Domenico (1862). Scritti politici (in Italian). M. Guigoni. p. 226.[ISBN unspecified]

- ^ "DIONISIO I il Vecchio (Διονύριος o πρεσβύτερος) tiranno di Siracusa" (in Italian). Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ Rohlfs, Gerhard (1967). "Greek Remnants in Southern Italy". The Classical Journal. 62 (4): 164–9. JSTOR 3295569.

- ^ a b "Gli artisti della Magna Grecia" (in Italian). Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- ^ a b "La pittura vascolare greca" (in Italian). Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- ^ "Riapre la collezione Magna Grecia: al MANN un passeggiata nella storia degli antichi tesori del sud" (in Italian). Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- ^ "Manifestazioni della cultura dell'Occidente greco. La pittura parietale" (in Italian). Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- ^ "Storia del Teatro nelle città d'Italia" (in Italian). Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ "Il teatro" (in Italian). Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ "Aristotele – Origini della commedia" (in Italian). Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ "Rintóne" (in Italian). Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ "Gli atleti greci, i campioni delle gare panelleniche" (in Italian). 9 August 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ Nestoros1988, Francesco Castagna. "Ipotesi sulla definizione di Pithekoussai come emporion o apoikia" (in Italian). Retrieved 12 July 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Cuma, la prima città greca in Italia" (in Italian). 29 June 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Sibari e la sibaritide" (PDF) (in Italian). p. 10. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "I GRECI IN CAMPANIA – LA PRIMA CITTÀ: CUMA" (in Italian). Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "Turi: una polis magnogreca tra tradizioni storiografiche e modelli politico-urbanistici" (PDF) (in Italian). p. 11. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Fantasia, Ugo (2012). La guerra del Peloponneso (in Italian). Carocci editore. p. 127. ISBN 978-88-430-6638-4.

- ^ Edward Augustus Freeman (1892). History of Sicily from the earliest time. Vol. 3. p. 80.

- ^ Gaetano De Sanctis, Scritti minori, 1970, p. 115. (In Italian).

- ^ Nanō Chatzēdakē; Museo Correr (1993). From Candia to Venice: Greek icons in Italy, 15th–16th centuries : Museo Correr, Venice, 17 September-30 October, 1993. Foundation for Hellenic Culture. p. 18.

- ^ Viscardi, Giuseppe Maria (2005). Tra Europa e "Indie di quaggiù". Chiesa, religiosità e cultura popolare nel Mezzogiorno (secoli XV-XIX) (in Italian). Rome: Ed. di Storia e Letteratura. p. 361. ISBN 978-88-6372-349-6.

- ^ Greece. Lonely Planet. 2008. p. 204.

- ^ Time. Time Incorporated. 1960. p. 4.

- ^ Greece. Michelin Tyre. 1991. p. 142. ISBN 978-2-06-701520-3.

- ^ Rocco Agrifoglio (29 August 2015). Knowledge Preservation Through Community of Practice: Theoretical Issues and Empirical Evidence. Springer. p. 49. ISBN 978-3-319-22234-9.

- ^ Lapo Mola; Ferdinando Pennarola; Stefano Za (16 October 2014). From Information to Smart Society: Environment, Politics and Economics. Springer. p. 108. ISBN 978-3-319-09450-2.

- ^ "Delimiting the territory of the Greek linguistic minority of Messina" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "Valle dei Templi" (in Italian). Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- ^ "Parco Valle dei Templi" (in Italian). Retrieved 17 May 2012.

- ^ Info on whc.unesco.org

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Ashby, Thomas (1911). "Velia". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 978.

- ^ Cord, David (2023). The Spring of Arethusa. pp. 7–9.

- ^ Canino, Antonio (1980). Basilicata, Calabria (in Italian). Touring Editore. p. 344. ISBN 9788836500215.

Sources[edit]

- Polyxeni Adam-Veleni and Dimitra Tsangari (editors), Greek colonisation: New data, current approaches; Proceedings of the scientific meeting held in Thessaloniki (6 February 2015), Athens, Alpha Bank, 2015.

- Antonaccio, Carla M. (2007). "Colonization: Greece on the Move 900–480". In Shapiro, H.A. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Archaic Greece. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Michael J. Bennett, Aaron J. Paul, Mario Iozzo, & Bruce M. White, Magna Graecia: Greek Art From South Italy and Sicily, Cleveland, OH, Cleveland Museum of Art, 2002.

- John Boardman, N. G. L. Hammond (editors), The Cambridge Ancient History, vol. III, part 3, The Expansion of the Greek World, Eighth to Sixth Centuries B.C., Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Boardman, John; Hammond, N.G.L. (1982). "Preface". In Boardman, John; Hammond, N.G.L (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. III.iii (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Giovanni Casadio & Patricia A. Johnston, Mystic Cults in Magna Graecia, Austin, University of Texas Press, 2009.

- Lucia Cerchiai, Lorenna Jannelli, & Fausto Longo (editors), The Greek cities of Magna Graecia and Sicily, Photography by Mark E. Smith, Los Angeles, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2004.ISBN 0-89236-751-2

- Giovanna Ceserani, Italy's Lost Greece: Magna Graecia and the Making of Modern Archaeology, New York, Oxford University Press, 2012.

- T. J. Dunbabin, The Western Greeks, 1948.

- M. Gualtieri, Fourth Century B.C. Magna Graecia: A Case Study, Jonsered, Sweden, P. Åströms, 1993.

- Mogens Herman Hansen & Thomas Heine Nielsen, An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- R. Ross Holloway, Art and Coinage in Magna Graecia, Bellinzona, Edizioni arte e moneta, 1978.

- Margaret Ellen Mayo, The Art of South Italy: Vases From Magna Graecia, Richmond, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 1982.

- Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli, The Greek World: Art and Civilization in Magna Graecia and Sicily, New York: Rizzoli, 1996.

- ———— (editor), The Western Greeks: Catalog of an exhibition held in the Palazzo Grassi, Venice, March–Dec., 1996, Milan, Bompiani, 1976.

- William Smith, "Magna Graecia." In Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, 1854.

- A. G. Woodhead, The Greeks in the West, 1962.

- Günther Zuntz, Persephone: Three Essays on Religion and Thought in Magna Graecia, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1971.

External links[edit]

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. XI (9th ed.). 1880. pp. 30–31.

- Ashby, Thomas (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). p. 319.

- Map. Ancient Coins.

- David Willey. Italy rediscovers Greek heritage. BBC News. 21 June 2005, 17:19 GMT 18:19 UK.

- Gaze On The Sea. Salentine Peninsula, Greece and Greater Greece. (in Italian, Greek and English)

- Oriamu pisulina. Traditional Griko song performed by Ghetonia.

- Kalinifta. Traditional Griko song performed by amateur local group.

- Second Interdisciplinary Symposium on the Hellenic Heritage of Southern Italy. Archaeological Institute of America (AIA). 11 June 2015. (Dates: Monday, 30 May 2016 to Thursday, 2 June 2016.)

- Sergio Tofanelli et al. The Greeks in the West: genetic signatures of the Hellenic colonisation in southern Italy and Sicily. European Journal of Human Genetics, (15 July 2015).