Niçard Vespers

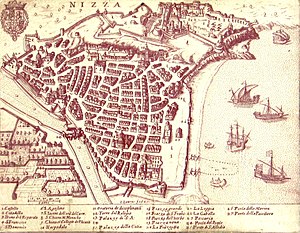

Pro-Italian protests in Nice, 1871, during the Niçard Vespers | |

| Date | 8–10 February 1871 |

|---|---|

| Location | Nice, France |

| Cause | annexation of the County of Nice to France and consequent policy of Francization of the territory and its inhabitants |

| Participants | Local ethnic Italians (Niçard Italians). |

| Outcome | Protests suppressed |

The Niçard Vespers (Italian: Vespri nizzardi [ˈvɛspri nitˈtsardi]; French: Vêpres niçoises) were three days of popular uprising of the inhabitants of Nice, in 1871, in support of the union of the County of Nice with the Kingdom of Italy.[1]

Background[edit]

After the Treaty of Turin was signed in 1860 between the Victor Emmanuel II and Napoleon III as a consequence of the Plombières Agreement, the county of Nice was ceded to France as a territorial reward for French assistance in the Second Italian War of Independence against Austria, which saw Lombardy united with the Italian kingdom of Sardinia.

King Victor-Emmanuel II, on 1 April 1860, solemnly asked the population to accept the change of sovereignty, in the name of Italian unity, and the cession was ratified by a regional referendum. Italophile manifestations and the acclamation of an "Italian Nice" by the crowd were reported on this occasion.[2] A referendum was voted on 15 April and 16 April 1860. The opponents of annexation called for abstention, hence the very high abstention rate. The "yes" vote won 83% of registered voters throughout the county of Nice, and 86% in Nice, partly due to pressure from the authorities.[3] This was the result of a masterful operation of information control by the French and Piedmontese governments, in order to influence the outcome of the vote in relation to the decisions already taken.[4] The irregularities in the referendum voting operations were evident. The case of Levens is emblematic: the same official sources recorded, faced with only 407 voters, 481 votes cast, naturally almost all in favor of joining France.[5]

The Italian language was the official language of the County, used by the Church, the town hall, taught in schools, used in theaters and at the Opera; though it was immediately abolished and replaced by French.[6][7] Discontent over annexation to France led to the emigration of a large part of the Italophile population, also accelerated by Italian unification after 1861. A quarter of the population of Nice, around 11,000 people from Nice, decided to voluntarily exile to Italy.[8][9] The emigration of a quarter of the Niçard Italians to Italy was known as the Niçard exodus.[10]

The French government implemented a policy of Francization of society, language and culture.[11] The toponyms of the communes of the ancient County were francized, with the obligation to use French in Nice,[12] as well as certain surnames (for example the Italian surname "Bianchi" was francized into "Leblanc", and the Italian surname "Del Ponte" was francized into "Dupont").[13]

History[edit]

The part of the Niçard Italians who decided to stay was subjected to a strong attempt at Francization - rejected in those years by the Niçard Italians - which caused much resentment against the French. The Italian irredentists in Nice made themselves the spokesman for this rejection through their leader, Giuseppe Garibaldi from Nice.

[...] The professor Angelo Fenochio, former editor of the newspaper Il Nizzardo published an indignant pamphlet, I Nizzardi e l'Italia, which stated that "the whole history of Nice is a protest against our separation from Italy, against our incorporation into France" and underlined the numerous manifestations of Italianness from Nice following the transfer. [...][14]

In 1871, with the proclamation of the French Third Republic, in the legislative elections held on 8 February, Giuseppe Garibaldi was elected to the National Assembly at Bordeaux, together with Luigi Piccon and Costantino Bergondi from Nice, with the specific mandate to abrogate the Treaty of Turin of 1860 with which the County of Nice had been ceded to Napoleon III.

In the political elections, the pro-Italian lists received 26,534 votes out of 29,428 votes cast.

[...] As soon as the result of the vote was known, an immense crowd left the town hall and with the cry of Viva Nizza, Viva Garibaldi, crossed the Ponte Nuovo, stopped in Piazza Massena, took Via Gioffredo, and stayed for a while in front of the Italian consulate and, retracing her steps, stood under the windows of the candidates who harangued the people, and were enthusiastically applauded. Around half past midnight the multitude, drunk with joy and enthusiasm for the victory obtained, was still walking the streets. [...][14]

In response, the French Republican government sent an army of 10,000 soldiers to Nice. They shut down the pro-Italian newspaper Il Diritto di Nizza and jailed many Italian irredentists in Nice.

Immediately the population of Nice reacted and from 8 to 10 February they rose up, but had the worst against the French army which appeased the revolt in blood. Many were imprisoned and wounded, according to the historian Giulio Vignoli. On February 13, 1871, the deputy Garibaldi was prevented from speaking before the National Assembly and presented his resignation.[15] The story of the Niçard Vespers of 1871 was told by Enrico Sappia in his book Nizza contemporanea, published in London and banned in France.[16]

[...] Enrico Sappia will remember that among the immense crowd that sang and praised Italy, there were those who carried a flag with the inscription INRI which meant "The Niçards will return Italians". While the crowd continued to shout: "Down with France! Long live Italy!", the gendarmes arrived and were unable to disperse it. The crowd shouting "Long live Italy" and "Long live Garibaldi" also tried to storm the prefecture whose windows were broken with stone throwing. Many arrests were made that same evening and the following morning. The publication of the newspaper La Voce di Nizza which had taken the place of Il Diritto di Nizza, suppressed by the French authorities, was prohibited. On February 19, a new newspaper Il Pensiero di Nizza came out which took over the political legacy of the first two. The riots of 8, 9 and 10 February, the three bellicose days, provided valid arguments and solid reasons for those who advocated a return of Nice to Italy, because they had good game in supporting the arbitrariness of French power . The Italian separatists took risks in the squares and streets of Nice to assert their ideas, taking many risks in the riots and challenging the authorities. [...][14]

After the Niçard Vespers of 1871, the irredentists who supported the Italian unification were expelled from Nice, completing the Niçard exodus. The most illustrious was Luciano Mereu, who was expelled from Nice with three other renowned Garibaldini from Nice: Adriano Gilli, Carlo Perino, and Alberto Cougnet.[17] Even the famous writer and art critic Giuseppe Bres was exiled by the French for a few years because of his participation at Niçard Vespers.

Subsequently and until the end of the century, in addition to the expulsion of various citizens of Nice who were moderately favorable to Italy and its unification, there was a further strong strengthening of the process of Frenchisation in all of the former County of Nice, with the closure of all the newspapers in Italian (such as the renowned La Voce di Nizza) and with the complete Frenchization of the toponyms of the County of Nice.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Vespri Nizzardi, di Giuseppe Andre'

- ^ Ruggiero, Alain (2006). Nouvelle Histoire de Nice (in French).

- ^ Ruggiero, Alain, ed. (2006). Nouvelle histoire de Nice. Toulouse: Privat. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-2-7089-8335-9.

- ^ Kendall Adams, Charles (1873). "Universal Suffrage under Napoleon III". The North American Review. 0117: 360–370.

- ^ Dotto De' Dauli, Carlo (1873). Nizza, o Il confine d'Italia ad Occidente (in Italian).

- ^ Large, Didier (1996). "La situation linguistique dans le comté de Nice avant le rattachement à la France". Recherches régionales Côte d'Azur et contrées limitrophes.

- ^ Paul Gubbins and Mike Holt (2002). Beyond Boundaries: Language and Identity in Contemporary Europe. pp. 91–100.

- ^ Peirone, Fulvio (2011). Per Torino da Nizza e Savoia. Le opzioni del 1860 per la cittadinanza torinese, da un fondo dell'archivio storico della città di Torino (in Italian). Turin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ ""Un nizzardo su quattro prese la via dell'esilio" in seguito all'unità d'Italia, dice lo scrittore Casalino Pierluigi" (in Italian). 28 August 2017. Archived from the original on 19 February 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ ""Un nizzardo su quattro prese la via dell'esilio" in seguito all'unità d'Italia, dice lo scrittore Casalino Pierluigi" (in Italian). 28 August 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ Paul Gubbins and Mine Holt (2002). Beyond Boundaries: Language and Identity in Contemporary Europe. pp. 91–100.

- ^ "Il Nizzardo" (PDF) (in Italian). Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ "Un'Italia sconfinata" (in Italian). 20 February 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Courrière, Henri (2007). "Les troubles de fevrier 1871 à Nice". Cahiers de la Méditerranée (in French) (74): 179–208. doi:10.4000/cdlm.2693. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ "Video with references to the Niçard Vespers and Enrico Sappia" (in Italian). Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ Letter from Alberto Cougnet to Giuseppe Garibaldi, Genoa, December 7, 1867, Garibaldi Archive, Milan, C 2582