Pompey's campaign against the pirates

| Pompey's campaign against the pirates | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Wars of the Roman Republic | |||||||

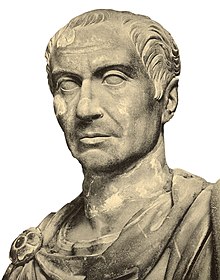

Bust of Pompey | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Roman Republic and Rhodes[1] | Pirates | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Pompey | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

270[2]/500[3] ships 120,000 soldiers[2][3] 4,000[2] /5,000[3] horsemen | More than 1,000 ships[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

377[5] /800 ships captured[6] 10,000 dead[5] 20,000 captured[7] 120 cities captured[5] | |||||||

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (January 2024) |

Pompey's campaign against the pirates refers to the final phase of the campaigns conducted by the Roman Republic against pirates infesting the eastern Mediterranean coast and damaging the eastern Roman provinces, completed in about 40 days under the command of Pompey in 67 BCE.[1][8]

The pirates no longer sailed in small groups, but in large hosts, and they had their own commanders, who increased their fame [by their exploits]. They despoiled and plundered first of all those who sailed, not leaving them alone even in winter [...]; then also those who were in the ports. And if one dared to challenge them on the open sea, he was usually defeated and destroyed. If he then managed to beat them, he was unable to capture them, because of the speed of their ships. So the pirates would go right back and loot and burn not only villages and farms, but whole towns, while others made them allies, so much so that they wintered there and set up bases for new operations, as if it were a friendly country.

— Cassius Dio, Roman History, XXXVI, 21.1-3.

Historical context[edit]

Rome's first intervention in the Aegean Sea in response to pirates occurred in 189 B.C., on the island of Crete, by Lucius Fabius Labeon, commander of the fleet, who nevertheless failed to obtain the return of Roman citizens taken captive by pirates.

The Romans intervened again, this time in the seas around Asia Minor, after establishing the first province in the East, Asia (133—129 BC). In 102 B.C., the consul Marcus Antonius[9] led a campaign in the Cilician area, so much so that as a result of reported successes over the piratical populations, a second Roman province, Cilicia, was established in 101–100 B.C. The latter province[10][11] initially consisted of Lycaonia,[10] Pisidia,[12] Pamphylia,[12] southeastern Phrygia,[12] and part of Cilicia Trachea, with the exclusion of its coastline, which was still, in part, infested with pirates.[10]

During the First Mithridatic War, Roman commander Quintus Brucius Sura,[13] who had first headed against Metrophanes with a small army (so much so that he had a naval clash with him, where he succeeded in sinking a large ship and a hemiolia), continued his navigation by raiding the harbor of the island of Skiathos, a den of pirates, where he crucified slaves and cut off the hands of freedmen who had taken refuge there (87 B.C.).[14] In the following years (86–85 B.C.E.), Sulla's legatus, Lucullus, was sent to collect a fleet consisting of ships from Cyprus, Phoenicia, Rhodes and Pamphylia, risking capture by pirates several times, although he had ravaged much of their coastline.[15]

At the end of the First Mithridatic War, the province of Asia was in a state of great misery. The conflict had led its territories to suffer constant assaults by numerous bands of pirates, which resembled regular fleets rather than bands of brigands. Mithridates VI, in fact, had set them up at a time when he was ravaging all the Roman coasts, thinking that he could not hold these regions for long. Their numbers had thus greatly increased, and this had led to continual attacks on ports, fortresses, and cities.[16] They had succeeded in capturing the cities of Iassus, Samos, Clazomenae, and even Samothrace, near which Sulla himself was at the time, and it was said that they succeeded in robbing the temple, which stood there, which had ornaments worth 1,000 Attic talents.[17] Plutarch adds that the ships of the pirates had certainly reached more than 1,000, and the cities captured by them numbered at least 400, having attacked and plundered places that had never been violated such as sanctuaries, including those of Claros, Didyma, Samothrace; the temple of Chthonia Terra at Hermione and of Asclepius at Epidaurus; those of Poseidon at Isthmus, Taenarum, and Kalaureia; those of Apollo at Actium and Lefkada; and those of Hera at Samos, Argos, and Lacinium. They also offered strange sacrifices at Olympus and celebrated some secret rites, including those of Mitra.[4]

Between 78 B.C. and 75 B.C. Publius Servilius Vatia served as proconsul of Cilicia,[18][19] achieving numerous victories over the pirates (equipped with light, fast warships), forcing them to take refuge in the Isauric hinterland.[20] Vatia, who was an energetic and resolute commander, almost immediately took the city of Olympus in Lycia, at the foot of the mountain of the same name, wresting it from the pirate leader, Zenicetus, who had died defending it. He then began his march through Pamphylia, where he took Phaselis, and entered Cilicia, where he captured the coastal fortress of Corycus. Having wrested all the coastal cities from the rebels, he had the army cross the Taurus for the first time to Roman arms and head inland, intending to take the capital of the Isaurians, Isaura, which he achieved by diverting the course of a river and taking the city by thirst. For his brilliant conduct, he was acclaimed imperator by the troops and received the Isauric agnomen.[21] Returning to Rome, he celebrated his triumph in 74 B.C.[22] Finally, it seems that the young Julius Caesar also took part in these campaigns as a military tribune.[23] Soon afterwards new piratical raids saw the city of Brindisi and the coast of Etruria stormed, as well as the seizure of a number of women from noble Roman families and even a couple of praetors.[18]

In 74 B.C. it was the turn of Marcus Antonius Creticus, father of Mark Antony, who led a new expedition to the seas around Crete, a military campaign that ended in defeat. A new expedition led by Quintus Caecilius Metellus Creticus, and supported by the cities of Gortina (now Gortyn) and Polyrrhenion, led to the gradual conquest of the main centers of anti-Roman resistance (Cydonia, Knossos, Eleutera, Lappa, Lytto, and Hierapytna), despite the conflict that arose between Quintus Metellus and the legate sent to the island by Pompey, Lucius Octavius,[24] who by virtue of the Gabinia law (lex Gabinia) had been granted extraordinary command for the fight against the pirates. Following the conquest of the island, Quintus Caecilius Metellus took the surname "Creticus."[25][26] In the course of this war, a curious episode is recounted about the young Julius Caesar: in 74 BC, on his way to Rhodes, a pilgrimage destination for young Romans of the upper classes eager to learn Greek culture and philosophy,[27] he was kidnapped by pirates, who took him to the island of Farmakonisi, one of the southern Sporades south of Miletus.[28] When they asked him to pay twenty talents, Caesar replied that he would hand over fifty talents and sent his companions to Miletus so that they could obtain the sum of money with which to pay the ransom, while he would remain on Pharmacussa with two slaves and his personal physician.[29] During his stay on the island, which lasted for thirty-eight days,[30] Caesar composed numerous poems and then submitted them to the judgment of his jailers; more generally, he maintained a rather peculiar behavior with the pirates, always treating them as if he was the one in charge of their lives and promising several times that once he was free he would have them all killed.[31] When his companions returned, taking with them the money that the cities had offered them to pay the ransom,[32] Caesar fled to the province of Asia, ruled by the propraetor Marcus Iuncus.[33] Upon reaching Miletus, Caesar armed ships and hurried back to Phacussa, where he captured the pirates without difficulty; then he went with the prisoners in tow to Bithynia, where Iuncus was overseeing the implementation of the wishes expressed by Nicomedes IV in his will. Here he asked the propraetor to provide for the punishment of the pirates, but the latter refused, instead attempting to seize the money taken from the pirates himself,[34] and then decided to resell the prisoners.[35] Caesar then, before Iuncus could put his plans into action, set sail, leaving Bithynia, and proceeded to execute the prisoners himself: he had them crucified after strangling them, so as to spare them a long and excruciating agony.[36] In this way, according to pro-Cesarian sources, he merely fulfilled what he had promised the pirates during their captivity,[37] and was even able to return the money his comrades had had to demand for ransom.[38]

In 70 B.C. Praetor Caecilius Metellus successfully fought the pirates infesting the seas of Sicily[18][39] and Campania,[40] who had gone so far as to sack Gaeta, Ostia[41] (in 69–68 B.C.) and kidnapped the daughter of Marcus Antonius at Cape Miseno.

Casus belli[edit]

By 69 B.C.E., Pompey was the favorite of the Roman masses even though many optimates were deeply suspicious of his intentions. His primacy in the state was enhanced by two extraordinary proconsular appointments, unprecedented in Roman history. In 67 B.C., two years after his consulship, Pompey was appointed commander of a special fleet to conduct a campaign against the pirates infesting the Mediterranean Sea.[42] Above all, Cilician pirates had invaded the seas, making relations between the different populations impossible, bringing war everywhere and generating heavy repercussions in maritime trade, including the very supply of grain for the city of Rome.[18] This was mainly due to the Mithridatic Wars, which had seen the proliferation of these bands that plundered ports, cities and trading ships unchallenged. At first, under their commander Isodorus, they limited themselves to striking the seas closest to them, between Crete, Cyrene, Achaia, and Cape Maleas, which, because of the riches of plundered booty, were renamed the "Golden Sea," and then they began to expand their range.[43]

The assignment given to Pompey was initially surrounded by controversy. The conservative faction of the Senate was suspicious of his intentions and afraid of his power. The optimates tried by all means to avoid it. Significantly, Caesar was among the handful of senators who supported Pompey's leadership from the beginning. The nomination then was advanced by the tribune of the plebs Aulus Gabinius, who proposed the Lex Gabinia, which gave Pompey command of the war against the Mediterranean pirates for three years,[44] with a broad power that ensured him absolute control over the sea and also over the coasts for 400 stadia inland (about 70 km),[2][45] placing him above any military leader in the east.[42] In addition to this, he was given the power to choose 15 legates from the Senate,[46] to be distributed in the main sea areas, take any money he wished from the public treasury and tax collectors, as well as 200 fully armed and equipped ships (soldiers and oarsmen).[47]

Forces in the field[edit]

Romans[edit]

The army that Pompey could have put together and deployed throughout the Mediterranean,[48] according to the Senate's provisions, was initially to count on 500 ships, 120,000 armed men (equal to about 30 legions) and 5,000 knights, subject to the command of 24 praetors and 2 quaestors,[3] and a total figure of 1,000 Attic talents.[2] It is known from Florus that Pompey also asked for help from the fleet of the Rhodians.[1] In reality the forces numbered no more than 270 ships (including hemiolias),[2] 4,000 horsemen[2] and 120,000 armed men,[2] under the command of 14 legates (according to Florus[49]) or 25 (according to Appian[2]) listed below:

- Gellius (consul in 72 BC), in charge of the Tuscan Sea;[49][50]

- Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus in the upper Adriatic Sea,[50] in whose employ may have been Pompey's young sons (Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus and Sextus Pompey) and not, as Florus would have it, the latter placed to guard the Egyptian Sea;[49][51]

- Plotius Varus on the Sea of Sicily;[49][50]

- Atilius in the Ligurian Sea (according to Florus[49]) or the Sardinian-Corsica Sea (according to Appian[50]);

- Pomponius in Gallia Narbonensis;[49][50]

- Torquatus in the Balearic Sea;[49][50]

- Tiberius Nero in the Strait of Gades;[49][50]

- Lentulus Marcellinus on the Libyan-African Sea;[49][50]

- Terentius Varro on the lower Adriatic to Acarnania;[49][50]

- Lucius Sisenna on the Peloponnese, Attica, Euboea, Thessaly, Macedonia and Boeotia;[50]

- Lucius Lollius on the upper Aegean and its islands to the Hellespont;[50]

- Publius Piso over Pontus Euxinus in the seas of Thrace and Bithynia, north of the Propontis;[50]

- Metellus over the eastern Aegean, southern Ionia, Lycia, Pamphylia, Cyprus, and Phoenicia;[49][50]

- Cepion over the Asiatic Sea;[49]

- Cato the Younger was to close the Propontis passages.[49]

Pirates[edit]

Plutarch recounts that the pirate ships had certainly reached over 1,000 by the end of the First Mithridatic War and had sacked/occupied at least 400 cities.[4] Below is how Appian describes them:

In the beginning [the pirates] roamed around with a couple of small boats, worrying the inhabitants of the area as [they were] thieves. As the war went on, they became more and more numerous and built larger ships. Having big gains, they did not stop [engaging in piracy] when Mithridates was defeated and called for peace, and then withdrew [from the conquered territories]. Having lost both their livelihood and their country due to the war, having fallen into extreme misery, they used the sea instead of land-holding; at first using vessels such as the pinnaces and the hemiolias, then with biremi and triremi, which sailed in actual squads under pirate leaders who were like the generals of an army. They occupied an unfortified city. They tore down the walls of the others, captured after a regular siege, looting them. They then took the wealthiest citizens away to their hidden headquarters, holding them hostage and demanding their ransom. They scorned the appellation of thieves, describing their spoils as war prizes. They had chained artisans to do work for them, and continually bringing them materials of wood, brass and iron.

— Appian of Alexandria, Mithridatic Wars, 92.

The pirates were so exalted by their easy gains that they decided not to change their way of life although the war was over. Instead, they compared themselves to kings, tyrants and great armies, and believed that united they would be invincible. They therefore built ships and all kinds of weapons. Their headquarters was at a place called Cragus in Cilicia (Coracesium), which they had chosen as their common anchorage and encampment. They owned fortresses with towers, and entire islands throughout the Mediterranean world. They chose as their "headquarters" the coast of Cilicia, which is rugged, with no easy mooring points and sheer cliffs. This is the main reason why all the pirates were called by the common name of Cilicians, although there were some who came from Syria, Cyprus, Pamphylia, Pontus and almost all eastern regions.[52] Their numbers later increased over time to several tens of thousands, scattered over the entire Mediterranean as far as the Pillars of Hercules.[18]

War[edit]

Pompey proceeded to divide the entire Mediterranean Basin into at least 15 districts, assigning to each a certain number of ships and a commander. Then with his forces, distributed in each sector of the sea infested with fleets of pirate ships, he began to pursue the enemy first in the West,[50] succeeding in tracking down their respective headquarters and capturing a considerable number of their ships, until he laid siege to the coast of Cilicia itself, in the East. Against the piratical forces in the latter region, Pompey decided to proceed in person with his 60 best ships. He had, therefore, first proceeded against the western piratical nucleus,[50] reducing it completely to obedience, from the Tyrrhenian Sea, to the Libyan Sea, Sea of Sardinia, Sea of Corsica and Sea of Sicily in only forty days,[50] thanks to his tireless energy and the zeal of his lieutenants.[53] Having finished these initial operations, he briefly passed through Rome and proceeded to Brindisi, then proceeding against the eastern pirate nuclei, which were certainly more "important" in numbers, ships and armaments.[50]

Some of the bands of pirates who were still free but asked for forgiveness were treated humanely [by Pompey], so much so that after their ships were seized and people handed over, no further harm was done to them; the others then had hope of being forgiven, tried to escape from the other commanders, and went to Pompey with their wives and children, surrendering to him. All these were spared, and through their help all those who were still free in their hiding places were tracked down, seized, and punished, as they knew they had committed unforgivable crimes.

— Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 27.4.

The most numerous and powerful bands of pirates had taken refuge with their families and treasures in a number of fortified fortresses and citadels near the Taurus Mountains. They were waiting with their powerful fleet for Pompey's attack near the promontory of Coracesium in Cilicia (modern Alanya), near which they were first defeated in battle and then besieged. Eventually, they decided to send ambassadors to the Roman proconsul and surrendered along with the rebellious cities and islands under their control, which were often difficult to storm.[50][54] The war on piracy had thus ended in less than three months with the surrender of all ships (71 captured and 306 delivered[5]), including some 90 with brass bows. Captured pirates amounted to more than 20,000 in number (10,000 had been killed[5]); they were not put to death, but neither were they allowed to go free: this would result in the recreation of straggling, poor, belligerent bands, with great danger for the future.[5][7][55]

Reflecting, then, that by nature man is not and does not become a savage or asocial creature, but is transformed by the unnatural practice of vice; where he can be softened by new customs through the change of place and life, then, if even ferocious beasts can extinguish their ferocious and savage way of being when these live in a gentler way of life, [Pompey] decided to transfer the men from the sea to the land, allowing them to live in a gentler way of life, in cities and cultivating the land. Some of them, therefore, were welcomed and integrated into the small, semi-deserted cities of Cilicia, to which he added additional territories; after rebuilding the city of Soli,[56] which had recently been devastated by Tigrane, king of Armenia, Pompey settled many of them there. For most of them, however, he gave as his residence the city of Dyme in Achaia,[5] which was then devoid of men and had much good land.

— Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 28.3-4.

He settled other pirates in Mallus, Adana, and Epiphanea.[5] Meanwhile, Metellus was in Crete to also eradicate the pirates on the island, from before the war against the pirates was entrusted to Pompey. He was related to that Metellus who had been Pompey's colleague in Hispania. After all, Crete was something of a second pirate base in importance, next to Cilicia. Although Metellus had killed many of them, he had not yet succeeded in completely destroying them.[57] Plutarch relates that those who had survived and were under siege by the Romans sent messages, begging Pompey to come to them. The Roman proconsul accepted the invitation and wrote to Metellus to suspend the siege, then sent one of his legates, Lucius Octavius, who entered three of the pirates' strongholds and fought alongside them, thus making Pompey obnoxious and putting him in a ridiculous situation, out of envy and jealousy toward Metellus.[58] Metellus, however, did not relent and eventually succeeded in capturing and punishing the pirates, sending Octavius back after insulting and beating him in front of the army.[59]

Consequences[edit]

Pompey's forces had thus succeeded in cleansing the entire Mediterranean Basin of pirates, wresting from them the island of Crete, the coasts of Lycia, Pamphylia, and Cilicia, demonstrating extraordinary discipline and organizational skill. Cilicia proper (Trachea and Pedias), which had been a den of pirates for over forty years, was thus finally subdued. Following these events the city of Tarsus became the capital of the entire Roman province. As many as 39 new cities were then founded.[6] The speed of the campaign indicated that Pompey was also talented as a general at sea, with strong logistical skills.

He was then commissioned to lead a new war against Mithridates VI, king of Pontus, in the East.[60] This command essentially entrusted Pompey with the conquest and reorganization of the entire eastern Mediterranean. It was the second command supported by Caesar in favor of Pompey. The latter led the campaigns from 65 B.C. to 62 B.C. with such military power and administrative capacity that Rome annexed much of Asia under firm control.

Pompey not only defeated Mithridates but also Tigranes the Great, king of Armenia, with whom he later made treaties. He conquered Syria, then under the rule of Antiochus XIII, and then moved toward Jerusalem, which he occupied in a short time. Pompey imposed a general reorganization on the kings of the new eastern provinces, cleverly taking into account the geographical and political factors associated with the creation of a new frontier of Rome in the east. With all his campaigns (Pompey defeated Mithridates, Tigranes II, Antiochus XIII) Pontus and Syria became Roman provinces and Jerusalem was conquered, all in Rome's name.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Florus, p. 7)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Appian, Mithridatic Wars, 94.

- ^ a b c d Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 26.2.

- ^ a b c Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 24.4-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Appian, Mithridatic Wars, 96.

- ^ a b Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 45.2.

- ^ a b Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 28.2.

- ^ Livy, p. 99.2)

- ^ Livy, p. 68.1)

- ^ a b c Piganiol (1989, p. 298)

- ^ Crawford (2008, p. 91)

- ^ a b c Piganiol (1989, p. 618, n. 11)

- ^ Brizzi (1997, p. 324)

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Sulla, 11.4-5.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Sulla, 24.1.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 24.1-3.

- ^ Appian, Mithridatic Wars, 63.

- ^ a b c d e Appian, Mithridatic Wars, 93.

- ^ Livy, Periochae ab Urbe condita libri, 90.

- ^ Florus, I, 41, 4.

- ^ Florus, I, 41, 5.

- ^ Fasti triumphales.

- ^ Canfora, p. 5.

- ^ Cassius Dio, XXXVI, 18-19.

- ^ Fasti Triumphales = AE 1889, 70 = AE 1930, 60 = CIL I, p.341.

- ^ Cassius Dio, XXXVI, 17.a.

- ^ Canfora, p. 8.

- ^ Velleius Paterculus, II,42

- ^ Suetonius, Caesar, 4; Plutarch, Caesar, 2,1.

- ^ Canfora, p. 9.

- ^ Plutarch, Caesar, 2.4

- ^ Velleius Paterculus, Roman History, II, 42.2.; Polyenus, VIII, 23.1.

- ^ Velleius Paterculus, Roman History, II, 42.3; Plutarch, Caesar, 2.6.

- ^ Plutarch, Caesar, 4.7.

- ^ Velleius Paterculus, II, 42.3.

- ^ Suetonius, Caesar, 74.1.

- ^ Plutarch, Caesar, 2.7.

- ^ Polyenus, VIII, 23.1.

- ^ Livy, Periochae ab Urbe condita libri, 98.3.

- ^ Florus, I, 41, 6.

- ^ Cassius Dio, XXXVI, 22.2.

- ^ a b Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 25.1-2.

- ^ Florus, I, 41, 1-3.

- ^ Cassius Dio, XXXVI, 23.4-5; 24-37.

- ^ Cassius Dio, XXXVI, 36bis.

- ^ Cassius Dio, XXXVI, 37.1.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 25.3.

- ^ Cicero, De Imperio Cn. Pompei ad Quirites oratio, 35.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Florus, I, 41, 9-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Appian, Mithridatic Wars, 95.

- ^ Leach, p. 70.

- ^ Appian, Mithridatic Wars, 92.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 26.3-4.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 28.1.

- ^ Florus, I, 41, 12-15.

- ^ Cassius Dio, XXXVI, 37.6.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 29.1.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 29.2-3.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 29.5.

- ^ Appian, Mithridatic Wars, 91.

Bibliography[edit]

- Appian. Mithridatic Wars. Archived from the original on October 3, 2015.

- Cassius Dio. Roman history, XXXVI.

- Cicero. De Imperio Cn. Pompei ad Quirites oratio.

- Florus. Epitome of Roman History, I, 41.

- Livy. Periochae ab Urbe condita libri.

- Plutarch. Life of Pompey.

- Plutarch. Life of Caesar.

- Polyaenus. Stratagems.

- Strabo. The Geography, XII.

- Valerius Maximus. Factorum et dictorum memorabilium libri IX.

- Velleius Paterculus. Historiae Romanae ad M. Vinicium libri duo, II, 31-33.

- Antonelli, Giuseppe (1992). "Mitridate, il nemico mortale di Roma". Il Giornale - Biblioteca Storica (49). Milan.

- Brizzi, Giovanni (1997). Storia di Roma. 1. Dalle origini ad Azio. Bologna: Pàtron. ISBN 88-555-2419-4.

- Canfora, Luciano (1999). Giulio Cesare. Il dittatore democratico. Laterza. ISBN 88-420-5739-8.

- Crawford, M. H. (2008). "Origini e sviluppi del sistema provinciale romano". La Repubblica imperiale: l'Età della conquista, Storia Einaudi dei Greci e dei Romani. 14. Milan: Il Sole 24 Ore.

- Leach, John (1983). Pompeo, il rivale di Cesare. Milan: Rizzoli. ISBN 88-17-36361-8.

- Piganiol, André (1989). Le conquiste dei Romani. Milan: Il Saggiatore. ISBN 88-04-32321-3.