Prostitution in Malta

Prostitution in Malta is itself legal, but certain activities connected with it, such as running a brothel and loitering, are not.[1][2] Certain offences are punishable by sentences of up to two years in prison.[3] In March 2008, police and the Malta Ministry for Social Policy signed a memorandum of understanding to formalize a screening process for all arrested persons engaged in prostitution to determine whether they were victims of trafficking or other abuses.[3] The law provides punishments of up to 6 years for involving minors in prostitution.[4]

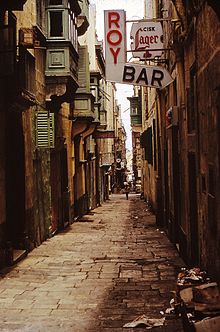

Prime Minister Joseph Muscat promised to discuss legalising prostitution in the buildup to the 2017 general election.[5] Valletta’s Strait Street (Maltese: Triq id-Dejqa), known locally as the 'Gut', was the centre of prostitution from the 1830s to the 1970s.[6] The Mello area of Gżira is known as a red-light district.[7]

History[edit]

Knights of Malta[edit]

Prostitution has occurred in Malta for centuries. When the Knights Hospitaller came to the country in 1530, the port of Vittoriosa contained many brothels. As well as Maltese prostitutes, there were also some from Greece, Italy, Spain and North Africa. The French king's geographer, Nicholas de Nicolai, was impressed by the number of prostitutes in the streets when he visited Vittoriosa in 1551,[8] Prior to the Great Siege of Malta in 1565, arrangements were made to evacuate the country's prostitutes to Sicily.[9]

When the Knights moved from Vittoriosa to the new capital Valletta, the prostitutes followed. As the Knights took vows of chastity, the prostitutes with them was seen as a scandal. Foreign prostitutes were expelled and the Maltese prostitutes confined to one area of the city.[8] At the time prostitutes wore a white shirt tied under their bust and a white cape.[8]

In 1608, inquisitor Leonetto della Cordoba was charged with seeking out prostitutes and dismissed as an inquisitor.[8] Prostitution was also common on Gozo.[8]

Towards the 17th century, there was harsh prejudice and laws towards those who were found guilty or who spoke openly of being involved in same-sex activity. English voyager and author William Lithgow, writing in March 1616, says a Spanish soldier and a Maltese teenage boy were publicly burnt to ashes for confessing to have practiced sodomy together.[10] Fearing a similar end, about a hundred males involved in same-sex prostitution sailed to Sicily the following day.[11]

Under a code introduced by Grand Master António Manoel de Vilhena in 1724, married men of means were fined if found guilty of use of the service of a prostitute, and expelled from the country on the third conviction. Lower-class men were whipped and sentenced to hard labour on the third offence. The 1784 code of Emmanuel de Rohan-Polduc barred foreign prostitutes from entering the country and placed restrictions on Maltese prostitutes. They were not allowed to open their doors between sunrise and sunset and were not allowed to enter pubs or taverns. Compulsory medical examinations were introduced.[12]

French period[edit]

Following the French occupation of Malta, prostitution rose.[8] Compulsory medical examinations continued[12] and the authorities opened hospitals in the monastery of Saint Scholastica and in Auberge de Bavière to treat soldiers with STIs.[8][13]

British period[edit]

After the country came under control of the British, prostitution increased again due to the number of sailors and soldiers stationed there.[8] Many married women worked as prostitutes, with their husbands' knowledge, due to economic hardship.[14]

Strait Street, in Valletta known locally as the 'Gut', was the centre of prostitution from the 1830s to the 1970s. Compulsory medical examinations continued until 1859 when it was realised that previous Grand Master codes were not legally enforceable. The prostitutes therefore refused to undergo the examinations.[12] As a result, the authorities, under the guidance of Governor John Le Marchant,[1] decreed under Ordinance IV of 1861, that all prostitutes should be examined by a police doctor three times a month in an attempt to control the spread of STDs.[1][8] If an infection was discovered, the prostitute was taken to hospital and kept there until cured.[1] This regulation in Malta was a great influence on Britain introducing the first of the Contagious Diseases Acts in 1864 and its subsequent extension.[15] The frequency of examinations was increased to 4 times a month in 1920.[8]

Although there were regulations to control STIs, there were no prostitution laws until 1898. A new law was introduced prohibiting brothels, and not more than one prostitute could live in the same house unless they registered with the police.[8] The law also forbade prostitutes to live on the ground floor, within 50 yards of a place of worship or adjacent to licensed premises.[1] In 1904 there were 152 registered prostitutes, although many more were unregistered.[8]

Malta was known by British sailors as the 'place with the three Ps: pubs, priests and prostitutes'.[16] Under the British Maltese moved to Egypt and Soho in London from 1905 to set up brothels there.

Sex trafficking[edit]

Malta is a source and destination country for women and children subjected to sex trafficking. Women and children from Malta have also been subjected to sex trafficking within the country. Women from Southeast Asia working as domestic workers, Chinese nationals working in massage parlors, and women from Central and Eastern Europe, Russia, and Ukraine working in nightclubs represent populations vulnerable to exploitation.[17]

Article 248A-G of the criminal code prohibits both sex and labour trafficking and prescribes penalties of four to 12 years imprisonment. The government has not obtained a conviction since early 2012. The government conducted three investigations and initiated prosecution of four defendants in one case, which remained pending at the close of 2016. These efforts were on par with 2015 when the government initiated investigation of two cases and prosecution of two defendants. Both the appeal of a 2012 conviction of a police officer for alleged collusion with a trafficker, and the prosecution of a 2004 case involving a police official, remained pending. There were no new investigations or prosecutions of government employees complicit in human trafficking offences.[17]

The United States Department of State Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons ranks Malta as a 'Tier 2' country.[17]

See also[edit]

- Strada Stretta – television series

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Attard, Eddie (16 March 2014). "Past laws regulating the oldest profession in Malta". Times of Malta. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ "Sex Work Law - Countries". Sexuality, Poverty and Law. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ a b "2008 Human Rights Reports: Malta". State.gov. 2009-02-25. Archived from the original on 2009-02-26. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

- ^ "Sexual Offences Laws - Malta". interpol.int. Archived from the original on 27 September 2001. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ "Prostitution in Malta". Malteasing.com. 8 May 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ "Sex, Lies, and Cobblestones: The Debaucherous Story Behind Malta's Most Notorious Street". Fodors Travel Guide. 18 January 2018. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ "Woman imprisoned for loitering at place known for prostitution in Gżira - TVM News". TVM English. 1 July 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Dalli, Kim (19 October 2014). "When prostitution in a car was a crime... but not on boat". Times of Malta. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ Bradford, Ernie (2011). Siege Malta 1940-1943. Pen and Sword. p. 165. ISBN 9781848845848.

- ^ Brincat, Joseph M. (2007). "Book reviews" (PDF). Melita Historica. 14: 448.

- ^ Buttigieg, Emanuel (2011). Nobility, Faith and Masculinity: The Hospitaller Knights of Malta, c.1580-c.1700. A & C Black. p. 156. ISBN 9781441102430.

- ^ a b c Savona-Ventura, Charles (2016). Contemporary Medicine in Malta [1798-1979]. Lulu.com. pp. 76–78. ISBN 9781326648992.

- ^ Savona-Ventura, C. (1998). "Human Suffering during the Maltese Insurrection of 1798" (PDF). Storja. 3 (6): 58.

- ^ Gregory, Desmond (1996). Malta, Britain, and the European Powers, 1793-1815. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. ISBN 9780838635902.

- ^ Howell, Philip (7 April 1999). "Prostitution and racialised sexuality: the regulation of prostitution in Britain and the British Empire before the Contagious Diseases Acts". University of Cambridge. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.473.5799.

- ^ Gordon, Andrew (2015). The Rules of the Game: Jutland and British Naval Command. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 9780141980331.

- ^ a b c "Malta 2017 Trafficking in Persons Report". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.