San Bruno Mountain

| San Bruno Mountain | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of San Bruno Mountain from San Francisco Bay overlooking part of Brisbane. | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,319 ft (402 m) NAVD 88[1] |

| Prominence | 1,114 ft (340 m)[2] |

| Coordinates | 37°41′15″N 122°26′08″W / 37.687440278°N 122.435555036°W[1] |

| Geography | |

| Location | San Mateo County, California, U.S. |

| Topo map | USGS San Francisco South |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Trail hike[3] |

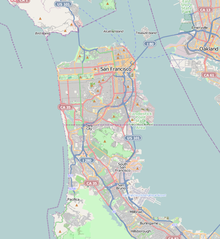

San Bruno Mountain is a fault-block horst in northern San Mateo County, California; its northern slopes rise in San Francisco. It is surrounded by San Francisco Bay and the cities of Brisbane, Colma, Daly City, and South San Francisco, and has played an important role in the history of all these communities.

Topped by a four mile long ridge, trails along the summit afford expansive views of the San Francisco Bay Area. Much of the mountain is in the 2,326-acre (941 ha) San Bruno Mountain State Park or the adjoining 83-acre (34 ha) State Ecological Reserve. Radio Peak (elevation 1,319 feet or 402 meters),[1] the highest point, serves the hilly Bay Area with several radio/TV broadcast towers.

It is not a part of the nearby Santa Cruz Mountains, whose northern-most peak on Montara Mountain lifts only eight miles from Radio Peak. The Santa Cruz range is on the Pacific tectonic plate, while San Bruno Mountain is on the North American Plate.

Distinct geology and weather set San Bruno Mountain apart from other California coastal areas.[4] The mountain soil provides habitat for rare and endangered plants (see below) and butterflies; the Callippe silverspot, Mission blue, and San Bruno elfin butterfly all inhabit mountain slopes.[5] The mountain is also a cradle for economically-useful plants; the low-growing evergreen "San Bruno Mountain Manzanita" (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) has become widely used in drought-resistant landscaping.[6]

Location[edit]

The southern border of San Francisco runs along the northern base of the range; Daly City's "top-of-the-hill" community at the westernmost point of the mountain was founded on John Daly's dairy farm by SF residents fleeing the 1906 quake.[7] The post-WW2 residential tracts of Southern Hills and Bayshore encircle the north side of the mountain - their construction inspired Malvina Reynolds song Little Boxes (a 1964 Billboard Hot 100 hit for singer Pete Seeger).[8][9] The Bayshore neighborhood features the 1941 Cow Palace indoor arena, and faces a large bay-landfill.

Brisbane is on an eastern prominence, while the residential portion of the community of South San Francisco spills into the southeastern valleys. Almost two miles of the southern flank of the mountain abuts the large cemeteries of Colma, many developed after the City and County of San Francisco evicted all burial grounds from the county in 1912.[10]

The 144-acre Guadalupe quarry on the south side of Guadalupe Canyon is presently owned and operated by American Rock and Asphalt, Inc.,[11] while the Crocker Industrial Park occupies much of the canyon floor. Radio towers occupy the highest (1,319 ft) peak, and may be accessed from the San Bruno County Park center, in the "saddle" between the north and south ridges.

A series of historic maps and photos of the area[12] may be viewed at the website of the City of Brisbane.

Topography, Geology, Climate[edit]

San Bruno Mountain is a part of the Franciscan Formation; sedimentary rock laid down in the Mesozoic, then uplifted as fault-blocks starting in the Pleistocene;[13] prior to the initial occurrence of the San Andreas transform-fault.[14] The formation is centered on present-day San Francisco, composed of small ranges trending northwest-to-southeast from the peninsula up into Marin County.

The mountain pairs two parallel ranges separated by the Guadalupe Valley and Colma Canyon and united by a saddle. The lower north range (also called Crocker Hills) attains a peak of 850 feet (259 m). The south range rises abruptly from Merced Valley at the south to the 1,319 feet (402 m) Radio Peak in a horizontal distance of only 0.8 miles (1.3 km). Slightly to the east of the highest peak, south of the main range, a small block reaches 581 feet (177 m) in South San Francisco, called Sign Hill because of large concrete letters placed by the city of South San Francisco. Into the early 1900s, San Francisco Bay still lapped directly against the eastern flank of San Bruno Mountain; but today the entire bay shoreline is fill.[15]

The region is drained by two streams: Guadalupe Valley Creek flows east between the two ranges to reach the Bay north of Brisbane - most of it now runs through underground culverts.[16] Colma Creek rises from a source in San Bruno Mountain State and County Park, runs west into Colma Canyon, then turns southeast and runs south along the base of the mountain (fed by Twelve-Mile Creek along Westborough Boulevard, and at least eight other streams) until it reaches the San Francisco Bay north of San Francisco International Airport.[17] Steelhead trout historically swam nearly to the headwaters of Colma Creek to spawn; boats carried supplies up to the Southern Pacific stop (now Molloy's Tavern on Old Mission Road in Colma).[18] Seasonal creeks to drain runoff cut ravines in the south face; after a heavy rain a 12-foot waterfall regularly appears in Juncus ravine behind Hillside School,[19] others may be found in Guadalupe canyon.[20]

Under the surface, we find late Cretaceous dark greenish-gray graywacke, a poorly sorted sandstone containing angular rock fragments (about 10% feldspar and detrital chert). The fragments imply a rapid erosion and burial in a deposit-basin, fossils are quite rare. Exposed graywacke can be observed on high ridges and on steep canyon walls. Microscopic fossils abound in the radiolarian chert seen on certain south facing slopes of San Bruno Mountain and at Point San Bruno. Finally, Serpentinite (the California State Rock) is a greenish soft metamorphic material; outcrops occur near Serbian Ravine and at Point San Bruno. With their unusual and diverse mineral composition, serpentine soils host a variety of rare plants which support even-rarer animal life.

An inland sand-dune (Colma formation) is found on the western slope behind Daly City's John F. Kennedy Elementary School, more than two-and-a-half miles from the ocean and elevated more than seven hundred feet above sea-level.[21] Reputedly, an exploratory gold mine exists on the mountain, above the Southern Hills.,[22][23] while the South San Francisco Land And Improvement Company registered a small silver, lead, and zinc mine in 1919.[24][25]

The mountain's climate is dominated by marine air flow heading inland, temperatures are mild to chilly in all seasons. Summer temperatures are further affected by marine fog shrouding the mountain mornings and evenings between late June and October, particularly the western slopes. Minimum temperature may fall below 50 °F (10 °C) in some sheltered valleys. Wind speed is higher than at surrounding locations;[26] on ridges winter storms regularly produce gusts from 50 to 80 miles per hour (80 to 129 km/h).[27] Precipitation is similar to surrounding cities, or about 22 inches (560 mm) per-annum; approximately 66 days-per-annum have measurable rainfall. Very occasionally, the mountain been covered with snow (recorded in December 1932, January 1952, January 1957, January 1962, February 5, 1976, February 26, 2011, and February 5, 2019).[28][29][30]

History[edit]

The earliest Spanish explorers on the San Francisco peninsula found the north end occupied by Ramaytush-speaking Ohlone peoples. The Yelamu seasonal hamlet of Siplichiquin occupied the southeastern point of the mountain, sheltered from western breezes and facing an oyster-laden cove; the occupants covered their dead with the shells.[31] Tested samples from the Siplichiquin shellmound indicate regular and continuous occupation from 3,200 BCE [32] (contemporary with the earliest dynasties of Ancient Egypt and likely a Hokan settlement pre-dating the Ohlone[33]) through AD 1800. Other prehistoric shell middens (names unrecorded and now unknown) have been unearthed during excavations over the past century - now denominated with CA-SMA numbers 44, 299, and 355.[34] These are on the south flank of the mountain where Colma Creek once entered the salt marshes that formerly lined San Francisco Bay. All of them are presently considered outlying seasonal encampments for residents of Siplichichiquin and Urebure, and none have been extensively studied.

Before the Gold-Rush[edit]

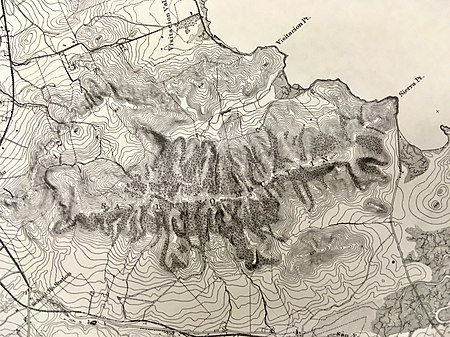

The Portola expedition visited San Francisco Bay in 1769; Sergeant Ortega's party of scouts crossed Montara Mountain to reach the Golden Gate; they are considered the first Europeans to see San Bruno Mountain. On December 2, 1774 Alta California governor Fernando Rivera y Moncada and four soldiers (possibly with Father Palóu) climbed the mountain and watched the sun rise across the bay.[35] The mountain was named by Bruno de Heceta to honor his patron saint,[36] and Sierra de San Bruno appears on the land-map of Rancho Cañada de Guadalupe drawn by Jean Jacques Vioget (presently in the collections of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley) some time in the 1840s.[37] That name was continued in use by the Geological Survey of California in 1865, which described the place as a short range extending from Sierra Point nearly to the Pacific Ocean.

San Bruno Mountain incorporates portions of five Spanish/Mexican land grants; the southernmost and largest being Rancho Buri Buri. Jose Antonio Sanchez, a member of the 1776 De Anza Expedition, was awarded Rancho Buri Buri in 1827, with confirmation by the Mexican government in 1835. Rancho Buri Buri extended from the bay salt flats to San Andreas Valley and from Daly City to Burlingame. Its northern extremity included "La Portezuela" (Doorway) between the western end of the mountain and the coastal upthrust along the San Andreas Fault, the juncture of Mission Street and El Camino Real. This was the main route between San Francisco and the peninsula before 1907, initially established to serve the missions, adopted by the Overland Stage in 1857, followed by the San Francisco and San Jose Railroad in 1863 and the Southern Pacific. Three other ranchos held minor portions on the northern flank of the mountain: Rancho Laguna de la Merced, Rancho Rincon de las Salinas y Potrero Viejo, and a corner of Rancho San Miguel all climbed the hills of the north range.

Rancho Canada de Guadalupe la Visitacion y Rodeo Viejo, however, contained most of the present day San Bruno Mountain, It included the present-day city of Brisbane, Guadalupe Valley, Crocker Industrial Park, Visitacion Valley and the rodeo grounds south of Islais Creek. In 1835 Governor Vallejo granted this rancho to Jacob P. Leese, his brother-in-law. Leese exchanged it for a rancho near Clear Lake owned by Yerba Buena character Robert T. Ridley and his wife Presentacion (daughter of Juana Briones de Miranda).[38] The Visitacion rancho was actioned after Ridley died in 1851, despite the claims of his widow.[39] In 1884 banker Charles Crocker acquired the largest part of the holdings of this rancho amounting to 3,997 acres (1,618 ha), and that land devolved to the Crocker Estate Company.

1850s-1960s[edit]

The United States Coast Survey sketch of San Francisco Bay drawn in 1853 from observations made from 1850 to 1852 labels the mountain as Abbey Hill,[40] which name appeared on U.S. Coast Survey maps until 1869. The United States Geological Survey surveyed the San Francisco area, producing a 15-minute topographic map in 1892[41] and updating it in 1899.[42]

The County of San Francisco discouraged graveyard-expansion in the 1880s, and prohibited burials after 1900. New cemeteries were established over the county line in Colma on the southern flank of the mountain. Holy Cross Roman Catholic Cemetery, went into service in 1887,[43] quickly followed by Jewish institutions Hills of Eternity Memorial Park and Home of Peace Cemetery which moved from San Francisco. The Chinese Six Companies established Hoy Sun Ning Yung Cemetery in 1898,[44] while the most recent (and sixteenth) development is the neighboring Golden Hill Memorial Park & Funeral Home, begun in 1994.

The road to the top of the mountain (Radio Road) does not appear on the 1950 USGS 7.5-minute topographic map,[45] but does appear on the 1956 edition.[46] In 1949 KRON (Channel 4) was the first television station to place a transmitter tower on Radio Peak, followed by KQED and KTVU, though these latter tenants moved their transmitters to Sutro Tower in the 1970s, while KTSF now transmits from Mount Allison. Radio Peak currently houses TV broadcasts for KRON, KOFY (and sister stations KCNZ and KQRM), KKPX, and KNTV. A number of FM radio stations built transmitter towers on the mountain, and in 2005, KNTV moved its transmitter to the mountain, on the former KCSM-TV tower. KTSF occupied the former KRON site until 2018, when it entered into a channel sharing agreement with KDTV-DT and moved to its site on Mount Allison. Radio transmitters presently on San Bruno Mountain include KIOI, KITS, KMEL, KMVQ, KOSF (formerly KSFX), KQED, and KSAN,

In 1954, construction was begun for an early-warning radar and missile-control site on the mountaintop. It became active in 1956, controlling Nike anti-aircraft defense systems at Fort Funston (SF-59) and Milagra Ridge (SF-51), and remained in service through March 1963. The site has been re-purposed, and no trace can now be seen.[47] The runways of San Francisco Airport are three miles from the peak; in 1998 a United Airlines 747 lost power in an engine and nearly crashed into the peak.[48]

Westbay controversy[edit]

In 1965, Westbay Community Associates announced a plan to level a portion of the mountain to fill 27 square miles (70 km2) of San Francisco Bay north of Sierra Point with landfill.[49] The proposal intended to create housing developments in the "Saddle" and in the landfill zone. A four-lane limited-access road to connect the Bayshore Road to Radio Road was constructed to service the traffic from the proposed development; named the Guadalupe Canyon Parkway, it was completed in 1968. In order to remove 250 million cubic yards (190,000,000 m3) of earth from the ridge, Westbay proposed using a conveyor belt system to transport the fill across Bayshore Boulevard and Bayshore Freeway to offshore barges, which would then deposit the material along the shores of the Bay.[50] Opposition by organizations such as Save The Bay[51] and the residents of Brisbane led to the defeat of Westbay's conveyor plan in June 1967 and eventual cessation of landfill operations at Sierra Point by December 1972.[50]

Protection Efforts[edit]

In 1970, the Crocker Land Company and Foremost/McKesson partnered in development company Visitacion Associates, and 3,600 acres of the undeveloped mountain real-estate was transferred to the new entity.[52] Visitacion announced development of 8,500 residential units and 2 million square feet of commercial and office-space, to begin construction in 1975. Active opposition to development on the mountain continued, organized as the Committee to Save San Bruno Mountain, and in 1972 San Mateo County voters approved Proposition A (a program for acquiring undeveloped land for county parks) by 147,805 to 74,167.[53] Years of litigation over this plan was settled with Visitacion and Crocker donating 546 acres on the main ridge, and selling 1,100 more to the County in 1978. The State purchased 256 additional acres at the "Saddle" in 1980, and placed them under County management.[54] In 1989, the state Wildlife Conservation Board purchased another 83 acres and created a San Bruno Mountain Ecological Reserve.

But, in 1978, the Mission blue butterfly was declared an endangered species. Visitacion and Crocker Land hired Los Angeles legal firm Nossaman LLP, and in 1982 environmental attorney Robert D. Thornton pioneered the Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) concept. An HCP is "a planning document designed to accommodate economic development to the extent possible by authorizing the limited and unintentional take of listed species when it occurs incidental to otherwise lawful activities"[55] He proposed creating the first such plan for the area around San Bruno Mountain. In the case of endangered San Bruno Mountain flora and fauna, it allowed new mountain developments at Terrabay, the Northeast Ridge in Brisbane (built in the mid 1990s, it's streets and civic features are named after endangered species they displaced), as well as at Village in the Park (built in 1985), Pointe Pacific (1986), and Bayshore Heights (1995) in Daly City. The accommodation offset for each development was to be the creation of equivalent new habitat nearby, which has not been substantially undertaken after forty years.[56]

Terra Bay development[edit]

The Terra Bay project was approved in the mid-1980s for development at the south and southeast base of San Bruno Mountain.[57] Terra Bay was constructed in three phases: the first phase constructed townhomes and detached houses; the second phase constructed more housing units, including one of the tallest buildings in South San Francisco,[58] a condominium tower named the Peninsula Mandalay, and the third phase constructed an office building named Centennial Towers.[59] The original developer, W.W. Dean & Associates, was unable to complete the project, and SunChase Holdings acquired the project in 1992, completing site preparation before selling the parcels for Phase I to Centex Homes.[60]

The Terra Bay site was known to include habitat for the Mission blue and Callippe silverspot butterflies; the original developer received a US$15,000 (equivalent to $46,000 in 2023) fine in 1983 for bulldozing part of the habitat during site preparation.[61] Under the terms established by the 1982 amendment to the Endangered Species Act, the nation's first-ever Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) was agreed upon, allowing developers to destroy the habitat of endangered species if substitute lands were made available.[62] SunChase agreed to fund ecological restoration to mitigate the impact of Terra Bay during the development of Phase I under the terms of the San Bruno HCP.[63] SunChase entered a joint venture with Myers Development for the development of Phases II and III;[60] although Phase III had 20 acres (8.1 ha) of land available for construction, the completed Centennial Towers was scaled back to fit on just 8 acres (3.2 ha),[64] partly in order to establish a buffer zone between the development and an ancient shellmound.

Although the shellmound had been noted as early as 1909,[65] a sample of 22 cubic metres (780 cu ft) of the shellmound conducted in 1989 by Holman & Associates (commissioned by W.W. Dean) revealed the massive shellmound contained human remains, and further, that the shellmound site is eligible for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places.[66] The Holman & Associates report was not made public for nearly ten years,[67] with leaked copies circulating privately in 1997, and a public copy incorporated in the draft Environmental Impact Report in 1998.[66] A lawsuit was settled out of court, resulting in the developer selling the land which included the shellmound and habitat for the Mission blue and Callippe silverspot butterflies to The Trust for Public Land,[68] who would incorporate the parcel into San Bruno Mountain State Park. Ultimately, Terra Bay Phase III was scaled back significantly from the original mixed-use retail/office proposal.[69][70] The shorter 12-story south tower was completed in 2009,[71][72] and the taller 21-story north tower was completed in 2020[73] after the project was acquired by a different developer.[74] The finished two-tower property was acquired by Ventas in late 2020.[75]

Life and Death on San Bruno Mountain[edit]

The title "San Bruno Mountain Hermits" refers was given to individuals known to inhabit San Bruno Mountain at various times: first in the 1980s,[76] and then in the 2000s.[77] Over the years, people sought refuge on the mountain from modern society and the homeless support system;[citation needed] some claimed to have cleared invasive or aggressive florae, performed fire prevention services, and engaged with local visitors who passed by their hut.[78]

In several cases, the San Mateo Sheriff or Parks Department have issued eviction notices, citing environmental degradation and illegal residency.[79] In each case, after a series of notices from park rangers and local authorities, these residents were forced to leave. San Bruno Mountain Watch has questioned governments' approaches to land management and the surrounding communities, and has promulgated the stories of these "hermits" in this context.[80]

Other inhabitants have perished in mountain encampments.[81] The mountain has been the site of at least one murder.[82] Human remains were found in the park area in 2012,[83] and later in 2020,[84] - these have not yet been identified.

Vegetation and ecology[edit]

The northern end of the San Francisco peninsula was primarily covered by plant communities of the grasslands, coastal scrub, redwood and mixed evergreen forest types prior to being overtaken by urban development. And, though much of the Pacific side of the Santa Cruz Mountains south of Montara Mountain is forested, grasslands and scrub predominated from Montara Mountain to the Golden Gate.[85] Along the San Francisco Bay, most of the original wetlands have been filled in by sediment from inland human activities (hydraulic mining, dredging, farmland runoff) and by purposeful landfill.[86] More than eighty small streams draining to the Bay provided riparian habitat along the peninsula.[87]

San Bruno mountain is not only one of the largest remaining examples of the original ecosystems, but also encompasses many microsystems in its relatively small area. The mineral content of the underlying rock and the high velocity marine air have evolved unusual varieties of flora and sustained specialized fauna that live among them.[26] There are a variety of habitats in this mountainous area, and notably the following rare or endangered flora:

- Coast rock cress (Arabis blepharophylla)

- Franciscan Wallflower (Erysimum franciscanum)

- Montara Manzanita (Arctostaphylos montaraensis)

- Niebla halei lichen

- Pacifica Manzanita (Arctostaphylos pacifica)

- San Bruno Mountain Manzanita (Arctostaphylos imbricata)

- San Francisco Campion (Silene verecunda)

- San Francisco Lessinga (Lessingia germanorum)

- San Francisco Owl's Clover (Orthocarpus floribundus)

The county reports that plague was detected in rodents on the mountain in the 1940s.[88]

Undeveloped portions of the mountain that sit between the state park and the counties of San Mateo and San Francisco are still privately owned and at risk for development.[89] Examples of these locations include the prehistoric sand dunes above Hillside Park in Daly City, and the eucalyptus groves bordering the Crocker and Southern Hills neighborhoods of Daly City. These areas are of great ecological significance, hosting the same plant and animal communities as found in the state park.

See also[edit]

- San Bruno Mountain State Park

- San Bruno Mountain Ecological Reserve

- List of California state parks

- List of summits of the San Francisco Bay Area

- Rancho Cañada de Guadalupe la Visitación y Rodeo Viejo

- Colma Creek

- Guadalupe Valley Creek

- Santa Cruz Mountains

- San Andreas Fault

- Franciscan Complex

- San Francisco garter snake

- Mission blue butterfly

- Mission blue butterfly habitat conservation

- San Bruno elfin butterfly

- Callippe silverspot butterfly

- United Airlines Flight 863

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "San Bruno Mountain Reset". NGS Data Sheet. National Geodetic Survey, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ^ "San Bruno Mountain, California". Peakbagger.com. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ^ "San Bruno Mountain Summit Loop". Trailspotting. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- ^ "California Department of Fish and Game's website, San Bruno Ecological Reserve".

- ^ Extracting useful data from imperfect monitoring schemes: endangered butterflies at San Bruno Mountain, San Mateo County, California (1982–2000) and implications for habitat management|Longcore et al.|2010 Springerlink.com|http://www.crecology.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/J.InsectConservation-Paper-01-07-2010.pdf

- ^ "Sustainable Conservation: BEYOND DROUGHT TOLERANT GUIDE".

- ^ "History of Daly City | Daly City, CA".

- ^ Little boxes. Schroder Music Co. 1963.

- ^ "Billboard Hot 100". Billboard.

- ^ Branch, John (5 February 2016). "The Town of Colma, Where San Francisco's Dead Live". The New York Times.

- ^ "Brisbane Quarry and mill, Brisbane, San Mateo Co., California, USA".

- ^ "Brisbane, CA". 7 September 2022.

- ^ "About the Mountain".

- ^ "The Franciscan Formation: Where the Rock and Plate Tectonic Cycles Converge".

- ^ Geology and Natural History of the San Francisco Bay Area; A Field-Trip Guidebook|Edited by Philip W. Stoffer and Leslie C. Gordon|2001|U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2188|https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/b2188/%7C#3: Geology of the Golden Gate Headlands

- ^ "Major Creeks of San Mateo County – Flows to Bay".

- ^ "Colma Creek Watershed". explore.museumca.org. Retrieved 2024-04-10.

- ^ "The Real Heart of the Mountain 1945-2014". California Native Plant Society. 28 February 2017.

- ^ "waterfall at (37.67560, -122.42409)".

- ^ "Twin-Plume Waterfall in San Bruno Mountain Park". YouTube.

- ^ "Daly City topographic map, elevation, terrain".

- ^ "Adventure to the Legendary Crystal Cave of San Bruno Mountain". 22 May 2014.

- ^ "Black Mountain Gold Mine Near Daly City, California".

- ^ "South San Francisco Land and Improvement Company Silver Mine in South San Francisco, California".

- ^ "South San Francisco Land and Improvement Company Silver Mine in South San Francisco, California".

- ^ a b "San Bruno Mountain Park Natural Features | County of San Mateo, CA".

- ^ "Atmospheric River Brings Historic Rainfall to the Bay Area".

- ^ "A white Christmas in the Bay Area? These snowy historical pics prove it to be possible". 12 December 2018.

- ^ "Rare snowfall San Francisco Bay area on 2 5 1976 of southern San Francisco and San Bruno Mountain California Stock Photo - Alamy".

- ^ "Rare snow falls on San Francisco's Twin Peaks as California gets rare dusting". Los Angeles Times. 5 February 2019.

- ^ "Buried in Shells".

- ^ "Historic Burial Site Could be Protected (CA)".

- ^ https://files.ceqanet.opr.ca.gov/252624-2/attachment/

- ^ https://files.ceqanet.opr.ca.gov/252624-2/attachment/ZoOIOfjQj93gfgLGsVi0vQDJnJHx2FFxOTEa_ZWl2Pe6EFY4QYrFfvPbeXtDpkvxuWMbKNsVjo0yFv_G0

- ^ On November 26 his expedition followed the Pajaro river to cross from Monterey Bay the Santa Clara Valley, then downstream along Coyote Creek to the Bay, where the expedition noted San Bruno Mountain in the distance. They reached the mountain on December 1, and attempted to climb it, but turned-back before dark.Alan K. Brown (December 1962). ""Rivera at San Francisco: A Journal of Exploration, 1774"". California Historical Society Quarterly. 41 (4): 325–341. JSTOR 43773364. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- ^ https://www.counterpunch.org/2022/03/18/saving-san-bruno-mountain-saints-sinners-saviors-and-the-saved/

- ^ Diseño del Rancho Cañada de Guadalupe, la Visitacion y Rodeo Viejo: Calif|Maps of private land grant cases of California|California Digital Library|https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/13030/hb1t1nb0bh/

- ^ "Robert T. Ridley & George Roch (Rock)".

- ^ "Finding Aid to the Documents Pertaining to the Adjudication of Private Land Claims in California, circa 1852-1892". www.oac.cdlib.org.

- ^ "Sketch J. No. 2 Showing the Progress of the Survey of San Francisco Bay and Vicinity Section X from 1850 to 1852".

- ^ https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/ht-bin/tv_browse.pl?id=97afbc4bfac9cde792f0aec869791b01 [bare URL]

- ^ https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/ht-bin/tv_browse.pl?id=b143647a6655b8a172244ff8540a351c [bare URL]

- ^ "Cemeteries".

- ^ "My China Roots".

- ^ https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/ht-bin/tv_browse.pl?id=aec1ca71ada10bcfd2f3536e45cd4177 [bare URL]

- ^ https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/ht-bin/tv_browse.pl?id=50511b26501e190734c3e4a160b19eda [bare URL]

- ^ "Cold War Era, 1952-1974 - Golden Gate National Recreation Area (U.S. National Park Service)".

- ^ Carley, William M. (19 March 1999). "United 747's Near Miss Initiates A Widespread Review of Pilot Skills". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 8 January 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ^ "50 years ago, San Bruno Mountain was almost cut in half". 15 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Brisbane: City of Stars, The First Twenty-Five Years (1961-1986)" (PDF). The City of Brisbane. 1989. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-09-26. Retrieved 2015-09-25.

- ^ Taugher, Mike (2011-11-05). "A pioneer remembers how she and friends saved the bay". Contra Costa Times. Archived from the original on 2011-12-09. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ "San Bruno Mountain - FoundSF".

- ^ Assembly Concurrent Resolution No. 134, Approving amendments to the Charter of the County of San Mateo, State of California, ratified by the qualified electors of the county at a general election held therein on the seventh day of November 1972|https://www.google.com/books/edition/Assembly_Bill/e4lgBtaWMNQC

- ^ "Mountain History".

- ^ What is a Habitat Conservation Plan?|US Fish & Wildlife Service|https://www.fws.gov/service/habitat-conservation-plans

- ^ "Butterflies and Bulldozers on an Island of Time -".

- ^ Wildermuth, John (18 November 1995). "South S.F. to Get New Homes / Terrabay project resumes after lengthy delays". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "The Peninsula Mandalay". Emporis. Archived from the original on 2020-11-23.

- ^ "Centennial Towers South". Emporis.[dead link]

- ^ a b "Domestic Master Planned Communities: Terra Bay; South San Francisco, CA". SunChase Holdings. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Habitat of rare butterflies bulldozed". The Day. AP. 6 July 1983. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Feuerstein, Adam (25 April 1997). "Butterflies vs. builders: The San Bruno compromise". San Francisco Business Times. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Pimentel, Benjamin (6 December 1996). "Accord on San Bruno Mountain / Long-stalled housing venture can proceed". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Centennial Tower". Skidmore, Owings, Merrill. 2009. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Nelson, N.C. (1909). "Shellmounds of the San Francisco Bay Region". University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology. 7 (4): 309–356. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ a b Dury, John; Townsend, Laird (2005). "Shellmound at San Bruno Mountain". FoundSF. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Andres, Fred (1 April 1998). "The Large Ohlone Shell Mound at San Bruno Mountain". Sierra Club San Francisco Bay Chapter GLS. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Buchanan, Wyatt (10 September 2004). "SAN BRUNO / Conservationists buy land in San Bruno". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Brown, Todd R. (15 March 2006). "Terrabay proposal comes to light". San Mateo County Times. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Terrabay back at it with two towers in Phase III project". San Francisco Examiner. 16 August 2006. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Murtagh, Heather (30 December 2008). "Second office tower on hold". San Mateo Daily Journal. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Murtagh, Heather (11 February 2009). "Centennial Tower open for tenants". San Mateo Daily Journal. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Genesis".

- ^ Walsh, Austin (24 December 2015). "New developer acquires Centennial Towers project: Keystone office project purchased for conversion to R&D space in South San Francisco". San Mateo Daily Journal. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "$1 billion: Landmark Bay Area office complex is bought". 16 October 2020.

- ^ Schooley, David (30 May 1985). "We All Request That Dwight Taylor Be Let Be".

- ^ Brown, Patricia (September 8, 2002). "Treehouse Residents Receive an Eviction Notice". The New York Times. Retrieved 2023-12-01.

- ^ Archives, San Bruno Mountain Watch (2018-11-05), Guardians of the Mountain, retrieved 2023-12-02

- ^ "We Must Have Them Leave". San Bruno Mountain Watch. November 5, 2018. Retrieved 2023-12-01.

- ^ "Flash!". San Bruno Mountain Watch. August 27, 2018. Retrieved 2023-12-01.

- ^ https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2006/12/14/body-found-in-san-bruno-mountain-homeless-encampment/

- ^ https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-cold-case-san-bruno-mateo-20140613-story.html

- ^ https://everythingsouthcity.com/2013/08/do-you-recognize-this-woman-found-dead-on-san-bruno-mountain/

- ^ https://www.cbsnews.com/sanfrancisco/news/human-remains-discovered-near-san-bruno-mountain/

- ^ "Peninsula Watershed Historical Ecology Study | San Francisco Estuary Institute".

- ^ "Large Parts of the Bay Area Are Built on Fill. Why and Where?". 6 February 2020.

- ^ "Guide to SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA CREEKS".

- ^ https://www.smcmvcd.org/plague

- ^ "San Bruno Mountain Park".

External sources[edit]

- "San Bruno Mountain". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2009-08-24.

- Environmental Services Agency of San Mateo County, information on history, trails, park map, activities, park hours.

- San Bruno Mountain State Park

- San Bruno Mountain Watch, whose mission is to preserve San Bruno Mountain's Native American village sites and endangered habitats.

- Trailspotting: Hiking San Bruno Mountain Description, Photos and GPS/mapping data

- Climate Survey of San Bruno Mountain, prepared for Crocker Land Company by Metronics Associates, Palo Alto, Ca., October 20, 1967

- Elizabeth McClintock and Walter Knight, A Flora of the San Bruno Mountains, San Mateo County, California, Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences, Fourth Series, Volume XXXII, no. 20, pp. 587–677, November 29, 1968

- J.D. Whitney, Geological Survey of California (1865)

- John Hunter Thomas, A Flora of the Santa Cruz Mountains (1960)

- USGS TopoView site <https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/topoview/viewer/#11/37.6634/-122.4155>.