Seven Sleepers

Seven Sleepers | |

|---|---|

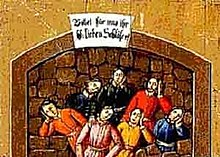

Illustration from the Menologion of Basil II | |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church Eastern Orthodox Church Oriental Orthodox Church Islam |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

| Feast | 27 July 4 August, October 22 (Eastern Christianity) |

The Seven Sleepers (Greek: ἑπτὰ κοιμώμενοι, romanized: hepta koimōmenoi;[1] Latin: Septem dormientes), also known in Christendom as Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, and in Islam as Aṣḥāb al-Kahf, lit. Companions of the Cave,[2] is a late antique Christian and later also Islamic legend. The Christian legend speaks about a group of youths who hid inside a cave[3] outside the city of Ephesus (modern-day Selçuk, Turkey) around AD 250 to escape Roman persecutions of Christians and emerged many years later. The Qur'anic version of the story appears in Sura 18 (18:9–26).[2]

Origins and propagation[edit]

The story appeared in several Syriac sources before Gregory of Tours's lifetime (538–594). The earliest Syriac manuscript copy is in MS Saint-Petersburg No. 4, which dates to the fifth century.[5]

The earliest known version of this story[clarification needed] is found in the writings of the Syriac bishop Jacob of Serugh (c. 450–521), who relies on an earlier Greek source, now lost.[6] Jacob of Serugh, an Edessan poet-theologian, wrote a homily in verse on the subject of the Seven Sleepers,[7] which was published in the Acta Sanctorum. Another sixth-century version, in a Syrian manuscript in the British Museum (Cat. Syr. Mss, p. 1090), gives eight sleepers.

Whether the original account was written in Syriac or Greek was a matter of debate, but today a Greek original is generally accepted.[8][5] The pilgrim account De situ terrae sanctae, written between 518 and 531, records the existence of a church dedicated to the sleepers in Ephesus.[5]

An outline of this tale appears in the 6th-century writings of Gregory of Tours and in History of the Lombards of Paul the Deacon (720–799).[9] The best-known Western version of the story appears in Jacobus de Voragine's Golden Legend (1259–1266). It also appears in BHO (Pueri septem),[10] BHG (Pueri VII)[11] and BHL Dormientes (Septem) Ephesi.[12]

Accounts of the Christian legend are found in at least nine medieval languages and preserved in over 200 manuscripts, mainly dating to between the 9th and 13th centuries. These include 104 Latin manuscripts, 40 Greek, 33 Arabic, 17 Syriac, six Ethiopic, five Coptic, two Armenian, one Middle Irish, and one Old English.[8][13] Byzantine writer Symeon the Metaphrast (died c. 1000) alluded to it.[7] It was also translated into Sogdian. In the 13th century, the poet Chardri composed an Old French version. The ninth-century Irish calendar Félire Óengusso commemorates the Seven Sleepers on 7 August.[14]

It[which?] was also translated into Persian, Kyrgyz, and Tatar.[5]

Dissemination in the West: story and relics[edit]

The story rapidly attained a wide diffusion throughout Christendom. It was popularized in the West by Gregory of Tours, in his late 6th-century collection of miracles, De gloria martyrum (Glory of the Martyrs).[7] Gregory claimed to have gotten the story from "a certain Syrian interpreter" (Syro quidam interpretante), but this could refer to either a Syriac- or Greek-speaker from the Levant.[5] During the period of the Crusades, bones from the sepulchres near Ephesus, identified as relics of the Seven Sleepers, were transported to Marseille, France, in a large stone coffin, which remained a trophy of the Abbey of St Victor, Marseille.

The Seven Sleepers were included in the Golden Legend compilation, the most popular book of the later Middle Ages, which fixed a precise date for their resurrection, AD 478, in the reign of Theodosius[dubious ].[15][16]

Christian story[edit]

The story says that during the persecutions by the Roman emperor Decius, around AD 250, seven young men were accused of following Christianity. They were given some time to recant their faith, but they refused to bow to Roman idols. Instead they chose to give their worldly goods to the poor and retire to a mountain cave to pray, where they fell asleep. The Emperor, seeing that their attitude towards paganism had not improved, ordered the mouth of the cave to be sealed.[4]

Decius died in 251, and many years passed during which Christianity went from being persecuted to being the state religion of the Roman Empire. At some later time—usually given as during the reign of Theodosius II (408–450)—in AD 447 when heated discussions were taking place between various schools of Christianity about the resurrection of the body in the day of judgement and life after death, a landowner decided to open up the sealed mouth of the cave, thinking to use it as a cattle pen. He opened it and found the sleepers inside. They awoke, imagining that they had slept but one day, and sent one of their number to Ephesus to buy food, with instructions to be careful.[7]

Upon arriving in the city, this person was astounded to find buildings with crosses attached; the townspeople for their part were astounded to find a man trying to spend old coins from the reign of Decius. The bishop was summoned to interview the sleepers; they told him their miracle story, and died praising God.[4] The various lives of the Seven Sleepers in Greek are listed and in other non-Latin languages at BHO.[17]

Account in the Quran[edit]

The story of the Companions of the Cave (Arabic: أصحاب الکهف, romanized: 'aṣḥāb al-kahf) is referred to in Quran 18:9-26.[2] The precise number of the sleepers is not stated. It is claimed in the Quran furthermore that people, shortly after the incident emerged, started to make "idle guesses" as to how many people were in the cave, Referencing: "My Sustainer knows best how many they were".[18] Similarly, regarding the exact period of time the people stayed in the cave, the Quran, after asserting the guesswork of the people that "they remained in the cave for 300 years and nine added", resolves that "God knows best how long they remained [there]." According to the 25th verse of Al-Kahf, the Companions of the Cave have slept for 300 years in the solar calendar and slept 309 in the lunar calendar since the lunar calendar is 11 days shorter than the solar, which explains the inclusion of the additional nine years.[19]

Number, duration and names[edit]

Early versions do not all agree on or even specify the number of sleepers. Some Jewish circles and the Christians of Najran believed in only three brothers; the East Syriac, five.[8] Most Syriac accounts have eight, including a nameless watcher which God sets over the sleepers.[5][20] A 6th-century Latin text titled "Pilgrimage of Theodosius"[clarification needed] featured the sleepers as seven people in number, with a dog named Viricanus.[21][22]

In Islam no specific number is mentioned. Qur'an 18:22 discusses the disputes regarding their numbers. The verse says:

Some will say, "They were three, their dog was the fourth," while others will say, "They were five, their dog was the sixth," only guessing blindly. And others will say, "They were seven and their dog was the eighth." Say, O Prophet, "My Lord knows best their exact number. Only a few people know as well." So do not argue about them except with sure knowledge, nor consult any of those who debate about them.[23]

The number of years the sleepers slept also varies between accounts. The highest number, given by Gregory of Tours, was 373 years. Some accounts have 372. Jacobus de Voragine calculated it at 196 (from the year 252 until 448).[8] Other calculations suggest 195.[5]

Islamic accounts, including the Qur'an, give a sleep of 309 years. These are presumably lunar years, which would make it 300 solar years. Qur'an 18:25 says, "And they remained in their cave for three hundred years and exceeded by nine."[24]

Bartłomiej Grysa lists at least seven different sets of names for the sleepers:[8]

- Maximian, Martinian, Dionisius, John, Constantine, Malchus, Serapion

- Maximilian, Martinian, Dionisius, John, Constantine, Malkhus, Serapion, Anthony

- Maximilian, Martinian, Dionisius, John, Constantine, Yamblikh (Iamblichus), Anthony

- Makṯimilīnā (Maksimilīnā, Maḥsimilīnā), Marnūš (Marṭūs), Kafašṭaṭyūš (Ksōṭōnos), Yamlīḫā (Yamnīḫ), Mišlīnā, Saḏnūš, Dabranūš (Bīrōnos), Samōnos, Buṭōnos, Qālos (according to aṭ-Ṭabarī and ad-Damīrī)

- Achillides, Probatus, Stephanus, Sambatus, Quiriacus, Diogenus, Diomedes (according to Gregory of Tours)

- Ikilios, Fruqtis, Istifanos, Sebastos, Qiryaqos, Dionisios (according to Michael the Syrian)

- Aršellītīs, Probatios, Sabbastios, Stafanos, Kīriakos, Diōmetios, Avhenios (according to the Coptic version)

Caves of the Seven Sleepers[edit]

Several sites[3] are attributed as the "Cave of the Seven Sleepers". As the popularity of the legend spread, an early Christian catacomb in Ephesus came to be associated with it, attracting scores of pilgrims. On the slopes of Mount Pion (Mount Coelian) near Ephesus (near modern Selçuk in Turkey), the grotto of the Seven Sleepers with ruins of the religious site built over it was excavated in 1926–1928.[25]: 394 The excavation brought to light several hundred graves dated to the 5th and 6th centuries. Inscriptions dedicated to the Seven Sleepers, dating to the ninth century and onwards, were found on the walls and in the graves. This grotto is still shown to tourists.

Other possible sites of the cave of the Seven Sleepers are in Damascus, Syria and Afşin and Tarsus, Turkey. Afşin is near the antique Roman city of Arabissus, to which the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian paid a visit. The site was a Hittite temple, used as a Roman temple and later as a church in Roman and Byzantine times. The Emperor brought marble niches from Western Anatolia as gifts for it, which are preserved inside the Eshab-ı Kehf Kulliye mosque to this day. The Seljuks continued to use the place of worship as a church and a mosque. It was turned into a mosque over time, with the conversion of the local population to Islam.

There is a cave near Amman, Jordan, also known as the Cave of Seven Sleepers, which has eight smaller sealed tombs present inside and a ventilation duct coming out of the cave.[26]

List of notable sites[edit]

Asia Minor[edit]

- Eshab-ı Kehf Cave, Ephesus, Turkey[3]

- Eshab-ı Kehf Cave, Tarsus, Turkey[27]

- Grotto of the Seven Sleepers, İzmir, Turkey[3]

- Eshab-ı Kehf Kulliye, outside Afşin, Turkey[3]

MENA region[edit]

- Mar Musa, monastery in Syria[3]

- Mount Qasioun, Damascus, Syria

- Cave of the Seven Sleepers, Al-Rajeb (Greater Amman), Jordan[3]

- Mosquée de Sept Dormants, Chenini, Tunisia[3]

China[edit]

Gallery[edit]

- Caves regarded as the cave from the story of the Seven Sleepers

-

Entrance to the cave, near Amman, Jordan

-

Graves in the Cave of the Seven Sleepers, Jordan

-

Nameplate of the cave, Jordan

-

The cave in Ephesus, Turkey

-

Eshab-ı Kehf Kulliye in Afşin with the cave inside, Turkey

-

Eshab-ı Kehf Cave in Tarsus, Turkey

Modern literature[edit]

Early modern[edit]

The account had become proverbial in 16th century Protestant culture. The poet John Donne could ask,

I wonder, by my troth, what thou and I

Did, till we loved? Were we not weaned till then?

But sucked on country pleasures, childishly?

Or snorted we in the Seven Sleepers' den?—John Donne, "The Good-Morrow".

In John Heywood's Play called the Four PP (1530s), the Pardoner, a Renaissance update of the protagonist in Chaucer's "The Pardoner's Tale", offers his companions the opportunity to kiss "a slipper / Of one of the Seven Sleepers", but the relic is presented as absurdly as the Pardoner's other offerings, which include "the great-toe of the Trinity" and "a buttock-bone of Pentecost."[28]

Little is heard of the Seven Sleepers during the Enlightenment, but the account revived with the coming of Romanticism. The Golden Legend may have been the source for retellings of the Seven Sleepers in Thomas de Quincey's Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, in a poem by Goethe, Washington Irving's "Rip van Winkle", H. G. Wells's The Sleeper Awakes. It also might have an influence on the motif of the "King asleep in mountain". Mark Twain did a burlesque of the story of the Seven Sleepers in Chapter 13 of Volume 2 of The Innocents Abroad.[29]

Contemporary[edit]

Edward Gibbon gives different accounts of the story in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

The Serbian writer Danilo Kiš retells the story of the Seven Sleepers in a short story, "The Legend of the Sleepers", from his book The Encyclopedia of the Dead.

The Italian author Andrea Camilleri incorporates the story in his novel The Terracotta Dog in which the protagonist is led to a cave containing the titular watchdog (as described in the Qur'an and called "Kytmyr" in Sicilian folklore) and the saucer of silver coins with which one of the sleepers is to buy "pure food" from the bazaar in Ephesus (Qur'an 18.19). The Seven Sleepers are symbolically replaced by lovers Lisetta Moscato and Mario Cunich, who were killed in their nuptial bed by an assassin hired by Lisseta's incestuous father and later laid to rest in a cave in the Sicilian countryside.

In Susan Cooper's The Dark Is Rising series, Will Stanton awakens the Seven Sleepers in The Grey King, and in Silver on the Tree, they ride in the last battle against the Dark.

The Seven Sleepers series by Gilbert Morris takes a modern approach to the story in which seven teenagers must be awakened to fight evil in a post-nuclear-apocalypse world.

John Buchan refers to the Seven Sleepers in The Three Hostages in which Richard Hannay surmises that his wife Mary, who is a sound sleeper, is descended from one of the seven who has married one of the Foolish Virgins.

Several languages have idioms related to the Seven Sleepers, including:

- Hungarian: hétalvó, literally a "seven-sleeper", or "one who sleeps for an entire week", is a colloquial reference to a person who oversleeps or who is typically drowsy.[30]: 8

- Irish: "Na seacht gcodlatáin" refers to hibernating animals.[31]

- Norwegian: a late riser may be referred to as a syvsover ("seven sleeper")[32]

- Swedish: a late riser may be referred to as a sjusovare ("seven sleeper").[33]

- Welsh: a late riser may be referred to as a saith cysgadur ("seven sleeper") – as in the 1885 novel Rhys Lewis by Daniel Owen, where the protagonist is referred to as such in chapter 37, p. 294 (Hughes a'i Fab, Caerdydd, 1948).

Feast day[edit]

The most recent edition of the Roman Martyrology commemorates the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus under the date of 27 July.[34] The Byzantine calendar commemorates them with feasts on 4 August and 22 October. Syriac Orthodox calendars gives various dates: 21 April, 2 August, 13 August, 23 October and 24 October.[5]

See also[edit]

- Epimenides

- King asleep in mountain

- The Men of Angelos

- Rip Van Winkle

- Seven Sleepers' Day

- The Three Sleepers: characters in the C. S. Lewis children's novel The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

References[edit]

- ^ "Koranion". Typographeion tōn katastēmatōn A. Kōnstantinidou. January 6, 1886 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c Archer, George (October 2016). "The Hellhound of the Qur'an: A Dog at the Gate of the Underworld". Journal of Qur'anic Studies. 18 (3). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press on behalf of the Centre for Islamic Studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies: 1–33. doi:10.3366/jqs.2016.0248. eISSN 1755-1730. ISSN 1465-3591. OCLC 43733991.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Cave of Ashabe Kahf (The Cave of the Seven Sleepers)". Madain Project. Archived from the original on 2 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ a b c Fortescue, Adrian (1909). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Witold Witakowski, "Sleepers of Ephesus, Legend of the", in Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage: Electronic Edition, edited by Sebastian P. Brock, Aaron M. Butts, George A. Kiraz and Lucas Van Rompay (Gorgias Press, 2011; online ed. Beth Mardutho, 2018).

- ^ Pieter W. van der Horst (February 2011). Pious Long-Sleepers in Greek, Jewish, and Christian Antiquity (PDF). The Thirteenth International Orion Symposium: Tradition, Transmission, and Transformation: From Second Temple Literature through Judaism and Christianity in Late Antiquity. Jerusalem, Israel. pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b c d Baring-Gould, S. (Sabine) (January 6, 1876). "Curious myths of the Middle Ages". London, Rivingtons – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c d e Bartłomiej Grysa, "The Legend of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus in Syriac and Arab Sources: A Comparative Study", Orientalia Christiana Cracoviensia 2 (2010): 45–59.

- ^ Liuzza, R. M. (2016). "The Future is a Foreign Country: The Legend of the Seven Sleepers and the Anglo–Saxon Sense of the Past". In Kears, Carl; Paz, James (eds.). Medieval Science Fiction. King's College London, Centre for Late Antique & Medieval Studies. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-9539838-8-9.

- ^ Peeters, P.; Société de Bollandistes (1910). Bibliotheca hagiographica orientalis. Robarts – University of Toronto. Bruxellis, apud editores [Beyrouth (Syrie) Imprimerie catholique]. pp. 1012–1022.

- ^ Bollandistes (1909). Bibliotheca hagiographica graeca. PIMS – University of Toronto. Bruxellis, Société des Bollandistes. pp. 1593–1599.

- ^ Bollandists (1898). Bibliotheca hagiographica latina antiquae et mediae aetatis. PIMS – University of Toronto. Bruxellis: [s.n.] pp. 2313–2319.

- ^ Hugh Magennis, "The Anonymous Old English Legend of the Seven Sleepers and its Latin Source", Leeds Studies in English, n.s. 22 (1991): 43–56.

- ^ Stokes, Whitley (1905). The Martyrology of Oengus the Culdee: Félire Óengusso Céli Dé. Harrison and Sons. p. 4.

- ^ "The Seven Sleepers". The Golden Legend. Archived from the original on 6 January 2003.

It is in doubt of that which is said that they slept three hundred and sixty-two years, for they were raised the year of our Lord four hundred and seventy-eight, and Decius reigned but one year and three months, and that was in the year of our Lord two hundred and seventy, and so they slept but two hundred and eight years.

- ^ Jacobus (1899). "XV — The Seven Sleepers". In Madge, H.D. (ed.). Leaves from the Golden Legend. C.M. Watts (illustrator). pp. 174–175 – via Google Books.

It is doubt of that which is said that they slept ccclxii. years. For they were raised the year of Our Lord IIIICLXXXIII. And Decius reigned but one year and three months and that was in the year of our Lord CC and LXX., and so they slept but iic. and viii. years.

- ^ Peeters, P.; Société de Bollandistes (25 October 2018). "Bibliotheca hagiographica orientalis". Bruxellis, apud editores [Beyrouth (Syrie) Imprimerie catholique] – via Internet Archive.

- ^ The Message of the Quran, by M. Asad, Surah 18:22.

- ^ The Message of the Quran, by M. Asad, Surah 18:25–26.

- ^ Said Reynolds, Gabriel (2008). "The Quran in its Historical Context - Reynolds et al". academia.edu. p. 127-128. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ Reynolds, Gabriel Said "The Qur'an and the Bible: Text and commentary" Yale University Press, 2018, p. 454.

- ^ Tobias Nicklas in: C. R. Moss et al. (eds.), The Other Side: Apocryphal Perspectives on Ancient Christian “Orthodoxies” (2017), p. 26.

- ^ "Juz 15 / Hizb 30 - Page 294". quran.com. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ^ Khattab, M., trans., Qur'an, "Al-Kahf—The Cave", 18:25, Quran.com.

- ^ de Grummond, N. T., ed., Encyclopedia of the History of Classical Archaeology (London & New York: Routledge, 1996), p. 394.

- ^ Cave of the Seven Sleepers (at Lonely Planet)

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

LPwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Gassner, John, ed. (1987). Medieval and Tudor Drama. New York: Applause. p. 245. ISBN 9780936839844.

- ^ Samuel Clements (1976). Lawrence Teacher (ed.). The Unabridged Mark Twain. Philadelphia PA: Running Press. pp. pp. 245–248.

- ^ Kohler, W. C., & Kurz, P. J., Hypnosis in the Management of Sleep Disorders (London & New York: Routledge, 2018), p. 8.

- ^ "Foclóir Gaeilge–Béarla (Ó Dónaill): codlatán". www.teanglann.ie.

- ^ Entry for syvsover, Sprakradet, Language Council of Norway.

- ^ "sju-sovare | SAOB".

- ^ Martyrologium Romanum, editio altera, (Typis Vaticanis, 2004, p. 416 ISBN 88-209-7210-7)

Further reading[edit]

- Ælfric of Eynsham (1881). . Ælfric's Lives of Saints. London, Pub. for the Early English text society, by N. Trübner & co.

External links[edit]

- Quran–Authorized English Version The Cave- Sura 18 – Quran – Authorized English Version

- "SS. Maximian, Malchus, Martinian, Dionysius, John, Serapion, and Constantine, Martyrs", Butler's Lives of the Saints

- Text containing the Seven Sleepers' commemoration as part of the Office of Prime.

- Sura al-Kahf at Wikisource

- Photos of the excavated site of the Seven Sleepers cult.

- Gregory of Tours, The Patient Impassioned Suffering of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus translated by Michael Valerie

- The Lives of the Seven Sleepers from The Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine, William Caxton Middle English translation.

- The Seven Sleepers of Ephesus by Chardri, translated into English by Tony Devaney Morinelli: Medieval Sourcebook. fordham.edu

- Medieval legends

- Legendary Greek people

- Saints from Roman Anatolia

- Groups of Christian martyrs of the Roman era

- Groups of Roman Catholic saints

- Quranic narratives

- Sleep in mythology and folklore

- 3rd-century Christian saints

- Rip Van Winkle-type stories

- Dogs in religion

- Decian dynasty

- Ancient Ephesians

- Septets in religion