Siege of Trebizond (1461)

| Siege of Trebizond | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Byzantine–Ottoman Wars | |||||||

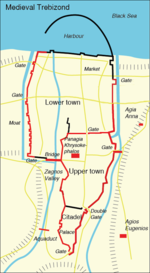

Fortification plan of (central) medieval Trebizond (modern Trabzon, Turkey). Current remains in red. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

80,000 infantry 200 galleys[2] | unknown | ||||||

Location within Turkey | |||||||

The siege of Trebizond was the successful siege of the city of Trebizond, capital of the Empire of Trebizond, by the Ottomans under Sultan Mehmed II, which ended on 15 August 1461.[1] The siege culminated a lengthy campaign on the Ottoman side, which involved coordinated but independent manoeuvres by a large army and navy. The Trapezuntine defenders had relied on a network of alliances, which would provide them with support and a workforce when the Ottomans began their siege. Still, it failed when Emperor David Megas Komnenos most needed it.

The Ottoman land campaign, which was the more challenging part, involved intimidating the ruler of Sinope into surrendering his realm, a march lasting more than a month through uninhabited mountainous wilderness, several minor battles with different opponents and finally the siege of Trebizond. The combined Ottoman forces blockaded the fortified city by land and sea until Emperor David agreed to surrender his capital city on terms. In return for his tiny realm, he would be given properties elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire, where he, his family, and his courtiers would live until their execution some two years later. For the rest of the inhabitants of Trebizond, The Sultan divided them into three groups. One group was forced to leave Trebizond and resettle in Constantinople. Another group became slaves either of the Sultan or of his dignitaries. The last group was left to live in the countryside surrounding Trebizond but not within its walls. Some 800 male children became recruits for his Janissaries, the elite Ottoman military unit, which required them to convert to Islam.[3]

With the last members of the Palaiologan dynasty having fled the Despotate of the Morea the previous year for Italy, Trebizond had become the last outpost of Byzantine civilization, which came to an end with Trebizond's fall.[4] "It was the end of the free Greek world," wrote Steven Runciman, who then noted that those Greeks still not under Ottoman rule lived "under lords of an alien race and an alien form of Christianity. Only among the wild villages of Mani, in the southeastern Peloponnese, into whose rugged mountains no Turk ventured to penetrate, was there left any semblance of liberty."[5][better source needed]

Background[edit]

The sources differ in their explanation of Mehmed's actual motivations for attacking Trebizond. William Miller quotes Kritoboulos as stating that Emperor David of Trebizond's "reluctance to pay tribute and the intermarriages with Hassan and the Georgian court provoked the Sultan to invade the Empire."[6] On the other hand, Halil İnalcık cites a passage from the 15th-century Ottoman historian Kemal Pasha-zade, who wrote:[7]

The Greeks used to live on the coasts of the Black and the Mediterranean Seas in the good habitable areas which were protected by the surrounding natural obstacles. In each area they were ruled by a tekvour, a kind of independent ruler, and they gave him regular taxes and military dues. Sultan Mehmed defeated and expelled some of these tekvours and wanted to do the same with the rest. The goal was to take away from these people all sovereignty. Thus he first destroyed the tekvour of Constantinople; he was considered as the principal tekvour and head of this people. Later on he had subdued successively the tekvours of Enos, Morea, Amasria (Amastris) and annexed their territories to the empire. Finally the Sultan's attention was drawn to the tekvour of Trebizond.

By the 1450s, the Ottoman Empire either occupied or had established hegemony over much of the territories the Byzantine Empire held before the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople in 1204. Many of Mehmed's campaigns in that period can be explained by assuming he was taking possession of the bits and fragments that he still did not rule directly: Enos fell after a lightning march in the winter of 1456;[8] after showing unusual patience with the surviving Palaiologoi ruling the Morea, who spent more time fighting each other than paying their tribute, Mehmed at last conquered all but one Byzantine fortress in that peninsula when Mistra fell on 29 May 1460;[9] Amasria was taken from the Genoese around the same time;[10] except for several islands in the Aegean Sea under the rule of various Latin lords, Trebizond was the one remaining piece of the former Eastern Roman Empire not under Mehmed's direct rule.[11]

Emperor John IV of Trebizond was aware of the threat Mehmed II posed for him at least as early as February 1451, when the Byzantine diplomat George Sphrantzes arrived in Trebizond seeking a bride for his emperor, Constantine XI. John had happily related to the visiting diplomat the news of the death of Sultan Murad II and that Mehmed II's youth meant that his empire could last longer and be blessed. Sphrantzes, however, was taken aback and explained to him that Mehmed's youth and seeming friendship were only ploys and that Mehmed was more of a threat to both monarchies than his father had been.[12]

Trebizond could rely on its substantial fortifications to defend itself. While solid walls protected it on all sides, and along the eastern and western walls, two deep ravines augmented the defenses, parts of the city lay outside them, such as the Meydan or marketplace, and the Genoese and Venetian quarters. These walls had withstood many previous sieges: in 1223, when the city walls had not been as extensive as in the mid-15th century, the defenders had defeated a Seljuk assault; not more than a few decades earlier, Shaykh Junayd had attempted to take the city by storm, yet with only a few soldiers the Emperor John had been able to hold him off.[13]

Nevertheless, John reached out to make alliances. Donald Nicol lists some of them: the emirs of Sinope and Karaman, and the Christian kings of Georgia.[14] His brother and successor David is thought to have commissioned Michael Aligheri—and possibly the questionable Ludovico da Bologna—to travel to Western Europe in 1460 searching for friends and allies.[15] But the most powerful and reliable ally of the Emperors of Trebizond was the ruler of the Aq Qoyunlu (or White Sheep Turkomen), Uzun Hasan. The grandson of a princess of the Grand Komnenoi, Uzun Hasan had made the Aq Qoyunlu into the most powerful tribe of Turkmen by defeating their rivals the Black Sheep; he had heard of the beauty of the Emperor John's daughter Theodora Komnene (or Despina Khatun), and in return for her hand, Uzun Hasan pledged himself to protect her home city with his men, his money, and his person.[14]

In 1456, Ottoman troops under Hizir Pasha assaulted Trebizond. According to Laonikos Chalkokondyles, Hizir raided the countryside, even penetrating the Meydan of Trebizond and capturing altogether about two thousand people. The city was deserted due to plague and likely to fall; John made his submission and agreed to pay an annual tribute of 2,000 gold pieces in return for Hizir freeing the captives he had taken. John sent his brother David to ratify the treaty with Mehmed II, which he did in 1458, but the Sultan raised the tribute to 3,000 gold pieces.[16]

A tribute of 3,000 gold pieces each year must have proven too much for the revenues of the Empire because either John or David approached their relative by marriage Uzun Hasan about transferring the allegiance of Trebizond from the Ottomans to him. Uzun Hasan agreed to this and sent envoys to Mehmed II. However, these envoys not only asked for the tribute to be transferred to the Aq Qoyunlu, they demanded on behalf of their master that Mehmed resume payment of tribute Mehmed's grandfather was said to have sent to the Aq Qoyunlu.[17] The sources disagree on exactly how Mehmed II answered, but both versions were ominous. In one version, he told the envoys, "it would not be long before they learned what they ought to expect from him."[18] In the other, Mehmed's response was, "Go in peace, and next year I will bring these things with me, and I will clear up the debt."[19]

Mehmed advances[edit]

In the spring of 1461, Mehmed fitted out a fleet comprising 200 galleys and ten warships. At the same time, Mehmed crossed the Dardanelles to Prusa with the Army of Europe and assembled the Army of Asia; one authority estimates the combined force consisted of 80,000 infantry and 60,000 cavalry.[2] According to Doukas, as word of the Sultan's preparations circulated the inhabitants of places as far apart as Lykostomion (or Chilia Veche) at the mouth of the Danube, Caffa in the Crimea, Trebizond and Sinope, and the islands of the Aegean Sea as far south as Chios, Lesbos, and Rhodes, whether or not they had acknowledged his hegemony, all worried they would be his target.[20] This appears to have been Mehmed's intent, for when later asked by a confidante where this force was destined, the Sultan scowled and said, "Be certain if I knew one hair of my beard knew my secret, I would pull it out and consign it to the flames."[21]

Sinope surrenders[edit]

Commanding the army, Mehmed led his land troops towards Ancyra, stopping to visit the tombs of his father and ancestors. He had written the ruler of Sinope, Kemâleddin Ismâil Bey, to send his son Hasan to Ancyra, and the young man was already there when Mehmed reached the city and received his overlord graciously.[22] Mehmed made his interests quickly known: according to Doukas, he informed Hasan, "Tell your father that I want Sinope, and if he surrenders the city freely, I will gladly reward him with the province of Philippopolis. But if he refuses, then I will come quickly."[23] Despite the extensive fortifications of the city and its 400 cannon crewed by 2,000 artillerymen, Ismail Bey caved into Mehmed's demands and accepted the lands Mehmed gave him in Thrace. There, he wrote a work on ritual prescriptions of Islam called Huulviyat-i Sultan and died in 1479.[24]

Mehmed had many reasons for seizing Sinope. It was well-situated and had good harbors. It also lay between Mehmed's territories and his ultimate objective, the city of Trebizond. Kritoboulos states that one major reason Mehmed took it for his own was that Hasan Uzun might seize it himself, and Mehmed knew "from many indications that he was plotting [to do that] in every way, and determined to seize it."[25]

Marching into Anatolia[edit]

Leaving Sinope to his admiral Kasim Pasha to arrange its government, Mehmed led his armies inland. The march was arduous for the men. Konstantin Mihailović, who served in the Ottoman army in this campaign, writing his memoirs decades later, recalled no landmarks between Sinope and Trebizond, yet the travails of the journey were still vivid in his memory:

And we marched in great force and with great effort to Trebizond—not just the army but the Emperor [i.e. Sultan Mehmed] himself: first, because of the distance; second, because of harassment of the people; third, hunger; fourth, because of the high and great mountains, and, besides, wet and swampy places. And also rains fell every day so that the road was churned up as high as the horses' belly everywhere.[26]

The path the Ottoman army took is not known. Kritoboulos states that Mehmed crossed the Taurus Mountains, becoming one of only four generals to have crossed them (the others being Alexander the Great, Pompey, and Timur).[27] However, as his translator Charles Riggs points out, to Kritoboulos all of the mountain systems of Asia Minor were part of the Taurus.[28] Doukas states that Mehmed led his soldiers across Armenia and the Phasis River, then ascended the Caucasus Mountains before reaching Trebizond.[29] This makes no sense when one examines a map, for both the Phasis River and the Caucasus are far to the east of their destination. However, Mihailović wrote in his memoirs that the army marched into Georgia,[26] so it is possible that Mehmed did make a show of force to intimidate the kings of Georgia from aiding their ally. Or, this is further proof that the soldiers in the Sultan's army had as little idea where they were going as the hairs in the Sultan's beard.

After 18 days of marching, one of the common soldiers made an attempt on the life of the Grand Vizier, Mahmud Pasha Angelovic. Two versions of this story exist: one in Kritoboulos and the other, moved from its proper place in the narrative through transmission by Konstantin Mihailović.[30][31] Kritoboulos states that no one had an explanation for this attempted murder, and before the assassin could be questioned he was "mercilessly cut to pieces by the army." Mihailović, on the other hand, states that the assassin was acting under the orders of Uzun Hassan and describes how the man was tortured for a week before he was executed. His body was left "beside the road for the dogs or wolves to eat." Both accounts agree that the Grand Vizier's wounds were minor, although Kritoboulos adds that Sultan Mehmed sent his personal physician, Yakub, to tend to Mahmud Pasha's wounds.[30]

The army continued for another 17 days.[32] Once the Sultan had passed Sivas and entered the lands of the Aq Qoyunlu, he sent Sarabdar Hasan Bey, the governor of the region of Amastris and Sebastea, forward to conquer a border fortress and lay waste to the lands around it. After continuing his march, the Sultan encountered Sara Khatun, the mother of Uzun Hasan; she had come to negotiate a peace treaty between the Sultan and her son. While Mehmed agreed to a peace treaty with Uzun Hasan, he refused to include Trebizond as a party.[33]

Kasim Pasha invests Trebizond[edit]

Meanwhile, Admiral Kasim Pasha had completed his work in Sinope and, assisted by a veteran seaman named Yakub, sailed to Trebizond. According to Chalkokondyles, upon reaching their destination the sailors disembarked, set fire to the suburbs, and began the investiture of the city.[34] However, Doukas states that despite daily assaults "no headway was made" to breaching the walls.[35] The men of Kasim Pasha's fleet had besieged the walls of Trebizond for 32 days when the first units of the Sultan's army under his Grand Vizier Mahmud Pasha Angelovic crossed over the Zigana Pass and took up positions at Skylolimne.[34]

Negotiations[edit]

Just as Constantine XI in 1453, Emperor David was allowed, before the Ottoman assault began in earnest, to capitulate. He could either surrender his city and not only save his life and wealth, as well as those of his courtiers, but also receive new estates that would provide him the same income; otherwise, further fighting could only end with the fall of Trebizond and David not only would lose his life and wealth, but any survivors would suffer the fate of a captured city.[36] The details of how this offer was delivered varies in the primary sources. According to Doukas, the Sultan "delivered an ultimatum to the emperor".[35] However, Doukas may have meant this in a general sense, not that Mehmed made the offer himself personally; Doukas omits many details about how the surrender was negotiated. Both Chalkokondyles and Kritoboulos state that his Grand Vizier, Mahmud Pasha Angelovic, arrived one day before the Sultan and began the negotiations for surrender. Where Chalkokondyles and Kritoboulos differ is the role that George Amiroutzes, the protovestiarios of Trebizond, played in these negotiations. Chalkokondyles states that Mahmud Pasha negotiated with David through George Amiroutzes, whom Chalkokondyles describes as the Pasha's cousin;[37] Kritoboulos omits all mention of Amiroutzes in these negotiations, stating that Mahmud Pasha sent as a messenger Thomas, the son of Katabolenos, to offer Emperor David this choice.[38]

Modern historians consider Chalkokondyles' account closer to the truth, envisioning a drama where David weighed these two choices. The walls of Trebizond were massive and elaborate; David expected his relative Hassan Uzun to arrive at any moment to relieve the siege, perhaps his ally, the King of Georgia, or perhaps even both. Meanwhile, George Amiroutzes was at this side, allegedly suborned by his cousin to betray David, advising his emperor that surrender would be the prudent course and reminding him what happened to Constantinople because Constantine refused Mehmed's offer; perhaps Amiroutzes even showed David letters from Sara Khatun informing him that no help would be forthcoming from that quarter.[39]

In the end, Emperor David Megas Komnenos chose to surrender his city and empire and trust that Sultan Mehmed would be merciful. Here again, the primary sources differ. According to Chalkokondyles, he sent Mahmud Pasha a message: he would surrender if given estates of equal value and if Mehmed married his daughter.[40] (Miller calls this last gesture, "the usual device of Imperial diplomacy".[41]) When the Sultan arrived the next day with the rest of his army, Mahmud Pasha reported the developments. The news that David's wife had escaped to Georgia angered the Sultan, and at first, he declared he wanted to storm the city and enslave all of its inhabitants. But after further deliberations with Mahmud Pasha, Sultan Mehmed accepted the offered terms.[40]

In contrast, Kritoboulos, who dedicated his history to Sultan Mehmed, describes the physical movement of the individuals involved: on the day Sultan Mehmed arrived, Thomas, son of Katabolenos, was sent before the gates of Trebizond to repeat the terms of surrender offered the day before. The people of Trebizond prepared "many splendid gifts", and a select group of "the very best men" emerged from the city and "made obeisance to the sultan, came to terms, exchanged oaths, and surrendered both the town and themselves to the Sultan."[42] After these exchanges, Emperor David left the city with his children and courtiers and did homage to the Sultan; the latter "received him mildly and kindly, shook hands, and showed him appropriate honors", then "gave both him [David] and his children many kinds of gifts, as well as to his suite."[43]

On 15 August 1461, Sultan Mehmed II entered Trebizond, and the last capital of the Romaioi had fallen. Both Stephen Runciman and Franz Babinger note this date was the 200th anniversary of Michael VIII Palaiologos' recapture of Constantinople from the Latin Empire.[44] Mehmed made a detailed inspection of the city, its defenses, and its inhabitants, according to Miller, who then quotes Kritoboulos, "He [Mehmed] ascended to the citadel and the palace and saw and admired the security of the one and the buildings and splendour of the other, and in every way he judged the city worthy of note."[45] Mehmed converted the Panagia Chrysokephalos cathedral in the center of the city into Fatih Mosque, and in the church of Saint Eugenios he said his first prayer, thus giving the building its later name, Yeni Cuma ("New Friday").[45]

Miller has collected two Turkish traditions about the fall of Trebizond. One tells how the citizens, expecting an army to arrive before dawn to force the Sultan to lift the siege, agreed to surrender at cock-crow. However, on that occasion, the roosters crowed in the small hours of the night, whereupon the Turks forced the city-dwellers to keep their word. The other describes how a girl, dressed in black, held out in the tower of the palace, and when all was lost, leaped to her death from its heights; consequently, that tower was called Kara kızın sarayı ("The Black Girl's palace").[46]

Aftermath[edit]

After taking possession of the city, Sultan Mehmed garrisoned his Janissaries in Trebizond's imperial castle; Kritobulos states that the garrison numbered 400.[47] He placed Emperor David, his family and his relatives, his officials, and their families with all of their wealth on Sultan's triremes which took them to Constantinople, where David and all three of his sons would be executed less than two years later and his daughter married off to the Grand Vizier Zagan Pasha.[48] The rest of the inhabitants of Trebizond According to Pseudo-Chalkokondyles were divided into three groups: one was forced to leave Trebizond and resettle in Constantinople; the next became slaves either of the Sultan or of his dignitaries; and the last was expelled from Trebizond to live in the countryside surrounding the city.[49] Kritobulos states that only "some of the most influential men of the city" were forced to resettle in Constantinople while stating nothing about the rest of the inhabitants.[50] The Sultan also took hundreds of children to become his personal slaves: while Kritobulos states that Mehmed took 1500 children of both sexes to be his slaves, Pseudo-Chalkokondyles writes only that he took 800 male children became recruits for his Janissaries, the elite Ottoman military unit, which required them to convert to Islam.[51]

According to Chalkokondyles, Mehmed appointed Kasim Pasha to be governor of Trebizond and had Hizir accept the submission of the villages around the city and in Mesochaldia, home of the Kabasites clan. Although Chalkokondyles implies that these communities quickly acquiesced to Ottoman rule,[52] Anthony Bryer has found evidence that some groups resisted their new Muslim overlords for as long as ten years. Mehmed proceeded overland back to Constantinople. Kritobulos is brief about his return march: where he detailed Sultan's challenges on the outward march, Kritobulos writes only that he had sent Sara Khatun back to Uzun Hassan "with many gifts and honors";[53] while Chalkokondyles notes the return journey was through "a strongly protected land and very inaccessible".[54] According to a colophon in a copy of Petrarch's Africa, Sultan's fleet returned by October 1461, their weapons and equipment almost unused.[55][better source needed]

Pope Pius II sought to rescue Trebizond, yet by his death in 1464, no Christian nation had undertaken a Crusade against the Ottomans.[56]

References[edit]

- ^ a b This is the date determined by Franz Babinger, "La date de la prise de Trébizonde par les Turcs (1461)", Revue des études byzantines, 7 (1949), pp. 205–207 doi:10.3406/rebyz.1949.1014

- ^ a b John Freely, The Grand Turk: Sultan Mehmed II, Conqueror of Constantinople and Master of an Empire (New York: Overlook Press, 2009), p. 67

- ^ William Miller, Trebizond: The last Greek Empire of the Byzantine Era: 1204–1461, 1926 (Chicago: Argonaut, 1969), p. 106

- ^ As pointed out by Donald M. Nicol, The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261–1453, second edition (Cambridge: University Press, 1993), with Trebizond died the last vestiges of the Roman Empire p. 401

- ^ Runciman, The Fall of Constantinople: 1453 (Cambridge: University Press, 1969), p. 176

- ^ Miller, Trebizond, p. 100

- ^ Inalcik, "Mehmed the Conqueror (1432–1481) and His Time", Speculum, 35 (1960), p. 422

- ^ Miller, "The Gattilusj of Lesbos (1355–1462)", Byzantinische Zeitschrift, 22 (1913), pp. 431f

- ^ Nicol, Last Centuries, pp. 396–398

- ^ Franz Babinger, Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time, edited by William C. Hickman and translated by Ralph Manheim (Princeton: University Press, 1978), pp. 180f

- ^ Nicol, Last Centuries, p. 401

- ^ Sphranzes, ch. 30. translated in Marios Philippides, The Fall of the Byzantine Empire: A Chronicle by George Sphrantzes, 1401–1477 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1980), pp. 58ff

- ^ Rustam Shukurov, "The campaign of Shaykh Djunayd Safawi against Trebizond (1456 AD/860 AH)", Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies, 17 (1993), pp. 127-140

- ^ a b Nicol, Last Centuries, p. 407

- ^ This embassy is described in Anthony Bryer, "Ludovico da Bologna and the Georgian and Anatolian Embassy of 1460–1461", Bedi Kartlisa, 19–20 (1965), pp. 178–198

- ^ Chalkokondyles 9.34; translated by Anthony Kaldellis, The Histories (Cambridge: Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library, 2014), vol. 2 p. 313. Miller, Trebizond, p. 87

- ^ Babinger, Mehmed the Conqueror, pp. 190f

- ^ Chalkokondyles, 9.70; translated by Kaldellis, The Histories, vol. 2 p. 353

- ^ Doukas 45.10; translated by Harry J. Magoulias, Decline and Fall of Byzantium to the Ottoman Turks (Detroit: Wayne State University, 1975), p. 257

- ^ Doukas, 45.16; translated by Magoulias, Decline and Fall, p. 258

- ^ Doukas, 45.15; translated by Magoulias, Decline and Fall, p. 258

- ^ Babinger, Mehmed, pp. 191

- ^ Doukas, 45.17; translated by Magoulias, Decline and Fall, p. 258

- ^ Babinger, Mehmed, pp. 192

- ^ Critobulus, IV.22–23; translated by Charles T. Riggs, The History of Mehmed the Conqueror (Princeton: University Press, 1954), pp.167f

- ^ a b Mihailović, chapter 31; translated by Benjamin Stolz, Memoirs of a Janissary, (Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers, 2011), p. 59

- ^ Kritoboulos, IV.26, 27; translated by Riggs, History of Mehmed, p. 169

- ^ Riggs, History of Mehmed, p. 168 n. 29

- ^ Doukas, 45.18; translated by Magoulias, Decline and Fall, p. 259

- ^ a b Kritoboulos, IV.32–36; translated by Riggs, History of Mehmed, pp. 171f

- ^ Mihailović, chapter 32; translated by Stolz (Memoirs of a Janissary, p. 62), who argues that this passage was moved to the campaign of 1471, which happened after Mihailović left the Ottoman service (p. xxviii)

- ^ Kritoboulos, IV.36; translated by Riggs, History of Mehmed, p. 172

- ^ Babinger, Mehmed, pp. 192f

- ^ a b Chalkokondyles, 9.74; translated by Kaldellis, The Histories, vol. 2 p. 359

- ^ a b Doukas, 45.19; translated by Magoulias, Decline and Fall, p. 259

- ^ Chalkokondyles, 9.75; translated by Kaldellis, The Histories, vol. 2 pp. 359–361. Doukas, 45.19; translated by Magoulias, Decline and Fall, p. 259; Kritoboulos, IV.41–44, translated by Riggs, History of Mehmed, pp. 173f

- ^ Chalkokondyles, 9.75-6; translated by Kaldellis, The Histories, vol. 2 pp. 359–363

- ^ Kritoboulos, IV.41; translated by Riggs, History of Mehmed, pp. 173f

- ^ This is a conflation of the accounts of Runciman (pp. 174f), Miller (pp. 102–104), Babinger (pp. 194f), and Nicol (pp. 408f).

- ^ a b Chalkokondyles, 9.76; translated by Kaldellis, The Histories, vol. 2 pp. 361–363

- ^ Miller, Trebizond, p. 103

- ^ Kritoboulos, IV.45; translated by Riggs, History of Mehmed, p. 174

- ^ Kritoboulos, IV.46; translated by Riggs, History of Mehmed, p. 175

- ^ Runciman, Fall of Constantinople, p. 175; Babinger, Mehmed, pp. 195f.

- ^ a b Miller, Trebizond, p. 104

- ^ Miller, Trebizond, p. 106f

- ^ Kritoboulos, IV.50; translated by Riggs, History of Mehmed, p. 175f. Chalkokondyless 9.76; translated by Kaldellis, The Histories, vol. 2 pp. 361–3

- ^ Doukas mentions David's "uncles and nephews": 45.19; translated by Magoulias, Decline and Fall, p. 259. Kritoboulos, IV.48; translated by Riggs, History of Mehmed, p. 175. Chalkokondyles, 9.77; translated by Kaldellis, The Histories, vol. 2 p. 363

- ^ Chalkokondyles, 9.79; translated by Kaldellis, The Histories, vol. 2 p. 365

- ^ Kritoboulos, IV.48; translated by Riggs, History of Mehmed, p. 175

- ^ Kritoboulos, IV.49; translated by Riggs, History of Mehmed, p. 175. Chalkokondyles, 9.79; translated by Kaldellis, The Histories, vol. 2 p. 365. Babinger, Mehmed, p. 195

- ^ Chalkokondykles, 9.77; translated by Kaldellis, The Histories, vol. 2 p. 363

- ^ Kritoboulos IV.51; translated by Riggs, History of Mehmed, p. 176

- ^ Kritoboulos, IV.52; translated by Riggs, History of Mehmed, p. 176. Chalkokondyles, 9.77; translated by Kaldellis, The Histories, vol. 2 p. 363

- ^ Ernest H. Wilkins, Harvard Library Bulletin, 12 (1958), pp. 321f

- ^ Babinger, Mehmed, p. 198