Tabula (game)

Tabula (Byzantine Greek: τάβλι), meaning a plank or board,[1] was a Greco-Roman board game for two players that has given its name to the tables family of games of which backgammon is a member.

History[edit]

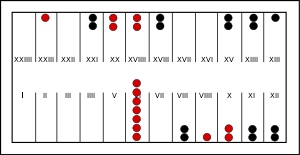

According to the Etymologiae by Isidore of Seville, tabula was first invented by a Greek soldier of the Trojan War named Alea.[3][4] The earliest description of "τάβλι" (tavli) is in an epigram of Byzantine emperor Zeno (r. 474–475; 476–491), given by Agathias of Myrine (6th century AD), who describes a game in which Zeno goes from a strong position to a very weak one after an unfortunate dice roll.[2] The rules of Tabula were reconstructed in the 19th century by Becq de Fouquières based upon this epigram.[2][5] The game was played on a board with a similar layout to that of a modern backgammon board: there were 24 points, 12 on each side.[2] Two players had 15 pieces each, and moved them in the same direction – anticlockwise – around the board, according to the roll of three dice.[2][5] A piece resting alone in a space on the board (a singleton) was vulnerable to being captured.[2] If a piece was moved to a point occupied by an enemy singleton, the latter was sent off the board and had to be re-entered on the next turn. The known differences compared with modern backgammon were: three dice were used, all pieces started off the board, both players moved in the same direction and there was no doubling die. It is not known whether players had to re-enter 'hit' pieces before playing those on the board, nor whether players had to gather all pieces in the fourth quadrant before bearing off. It is also not clear whether there was a "bar".[6]

In the epigram, Zeno was white (red in illustration) and had one point with seven pieces on it, three points with two pieces and two singletons, pieces that stand alone on a point and were therefore in danger of being put outside the board by an incoming opposing piece. Zeno threw the three dice with which the game was played and obtained 2, 5, and 6. Zeno could not move to a space occupied by two opposing (black) pieces. The white and black pieces were so distributed on the points that the only way to use all of the three results, as required by the game rules, was to break the three points with two pieces into singletons, thus exposing them to capture and ruining the game for Zeno.[2][6]

Tabula was most likely a later refinement of ludus duodecim scriptorum, with the board's middle row of points removed, and only the two outer rows remaining.[5]

Today, the word Tavli (τάβλι) is still used to refer to various tables games in Greece,[7] as well as in Syria and Turkey (as tavla), Bulgaria (as tabla) and in Romania (as table); in these countries, tables games remain popular in town squares and cafes.

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Rich 1881, p. 641: "TAB'ULA (πλάξ, σανίς, πίναξ). A plank or board..."

- ^ a b c d e f g Austin 1934, pp. 202–205.

- ^ Lapidge & O'Keefe 2005, p. 60.

- ^ Barney et al. 2006, XVIII.lx–lxix.2 (p. 371): "lx. The gaming-board (De tabula) Dicing (alea), that is, the game played at the gaming-board (tabula), was invented by the Greeks during lulls of the Trojan War by a certain soldier named Alea, from whom the practice took its name. The board game is played with a dice-tumbler, counters, and dice."

- ^ a b c Austin 1935, pp. 76–82.

- ^ a b Bell 2012, pp. 33–35.

- ^ Koukoules 1948, pp. 200–204.

Sources[edit]

- Austin, Roland G. (1934). "Zeno's Game of τάβλι". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 54 (2): 202–205. doi:10.2307/626864. JSTOR 626864.

- Austin, Roland G. (February 1935). "Roman Board Games. II". Greece & Rome. 4 (11): 76–82. doi:10.1017/s0017383500003119. JSTOR 640979.

- Barney, Stephen A.; Lewis, W.J.; Beach, J. A.; Berghof, Oliver (2006). The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-13-945616-6.

- Bell, Robert Charles (2012) [1979]. Board and Table Games from Many Civilizations. New York: Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 9780486145570.

- Koukoules, Phaidon (1948). Vyzantinon Vios kai Politismos. Vol. 1. Collection de l'institut français d'Athènes.

- Lapidge, Michael; O'Keefe, Katherine O'Brien (2005). Latin Learning and English Lore: Studies in Anglo-Saxon Literature for Michael Lapidge. Toronto: Toronto University Press. ISBN 978-0-80-208919-9.

- Rich, Anthony (1881). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. New York: D. Appleton & Company.