Tel al-Zaatar massacre

| Tel al-Zaatar massacre | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Lebanese Civil War | |

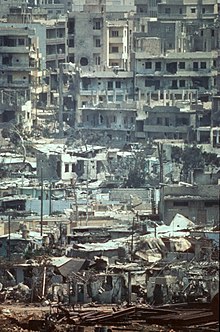

The destroyed camp (from the ICRC archives) | |

| Location | Tel al-Zaatar camp, Dekwaneh, Beirut |

| Date | 4 January – 12 August 1976 |

| Target | |

Attack type | Massacre |

| Deaths | 3,000 Palestinians killed[1] |

| Perpetrators | |

| Motive | Anti-Palestinian sentiment |

The Tel al-Zaatar massacre was an attack on Tel al-Zaatar (meaning Hill of Thyme in Arabic), a UNRWA-administered refugee camp housing Palestinian refugees in northeastern Beirut, that ended on August 12, 1976 with the massacre of 1,500[2][3][4] to 3,000 people.[5] The siege began in January of 1976 with an attack by Christian Lebanese militias led by the Lebanese Front as part of a wider campaign to expel Palestinians, especially those affiliated with the opposing Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from northern Beirut.[6] After five months, the siege turned into a full-scale military assault in June and ended with the massacre in August 1976. [7]

Background

At the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War, the country was home to a disproportionately large Palestinian population, which was divided along political lines.[8] Tel al-Zaatar was a refugee camp of about 3,000 structures, which housed 20,000 refugees in early 1976, and was populated primarily by supporters of the As-Sa'iqa faction within the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).[8] Many of the original inhabitants left to fight with As-Sa'iqa between January and June 1976, and this led to the Arab Liberation Front, another PLO faction, gradually assuming de facto control of the camp.[8] The PLO fortified Tel al-Zaatar and began using the camp to cache munitions and supplies for its armed wing.[8]

On April 13, 1975, a group of Phalangist[9] militiamen led an ambush on a bus that was on its way to the Tel al-Zaatar camp, killing twenty-seven and injuring nineteen.[10] More conflict ensued and following the killing of five Phalangists in the Christian controlled area of Fanar on December 6, 1975, Maronite local militia captured hundreds of Muslims in East Beirut at random. This led to a reactivation of battlefronts between the rival factions and the Tel al-Zaatar camp became a target of both the Phalangists and the NLP Tigers.[11]

By 1976, Tel al-Zaatar was the only Palestinian enclave left in the Christian-dominated area of East Beirut. It is one of the oldest and largest camps in the country.[12] Christian militias such as the Kataeb Regulatory Forces and the Guardians of the Cedars began attacking Palestinian refugee camps shortly after the war began due to the PLO's support for Muslim and leftist factions.[13] On January 18, they forcibly took control of the Karantina district and carried out the Karantina Massacre.[14]

The Christian forces were initially leery of escalating PLO involvement in the war, but Karantina was inhabited partly by Lebanese Muslims and was located along the main road they needed to resupply their positions in Beirut, so it was considered a legitimate target.[13] However, the PLO joined Muslim militias in retaliating for the Karantina Massacre by massacring the Christian population of Damour.[13] Damour was a stronghold for the National Liberal Party (NLP), a Christian faction affiliated with Lebanese Front, which led to the Christian militias declaring war on the PLO by the end of January.[15]

Tel al-Zaatar was immediately surrounded by 500 troops from the Kataeb Regulatory Forces, 500 from the NLP's armed wing (the Tigers Militia), and 400 others from various other militias, namely the Guardians of the Cedars.[15] The militias were joined by about 300 members of the Lebanese security forces.[15] They were equipped with Super Sherman tanks and a squadron of Panhard AML-90 armoured cars.[15]

Starting on June 23, Maronite groups begin confronting the rival enclaves within Christian dominated territories. This was in order to disrupt the land and sea supplies of these enemies and was part of the attack against the Tel-El Zaatar camp.[16] There were 1,500 armed PLO fighters inside the camp at the time.[17] They were mostly affiliated with As-Sa'iqa and the Arab Liberation Front.[17] There were also smaller groups of fighters from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command.[17] To complicate matters further, there were unaffiliated fighters present who fought under the PLO umbrella but did not support any one faction, mostly foreign fedayeen.[17] Factionalism within the camp contributed greatly to the success of the siege, as most of the As-Sa'iqa militants and As-Sa'iqa supporters left.[17]

The siege

Competing reports from the NLP Tigers and Palestinian groups came to light with regards to the beginning of the siege. Representatives of the NLP Tigers claimed that the Palestinians were threatening the peace while opposing Palestinian factions claimed that the Palestinians were peaceful and didn’t break the ceasefire.[18] The siege began in January 1976 when a van full of essential items such as food and medical supplies was stopped from entering the camp.[19] From the January 4 to January 14, Maronite guerrillas obstructed the Palestinian camps of Tel El Zaatar and Dubaya as part of this continued offensive.[20] Obtaining water throughout the siege was difficult and doctors reported that obtaining water led to up to 30 injuries per day.[21]

From June 22 onward, the Tigers militia led by Danny Chamoun, and many Christian residents of Ras el-Dekweneh and Mansouriye controlled by Maroun Khoury intensified the blockade to a full-scale military assault that lasted 35 days.

The Al-Karamah Hospital in the camp received the sick and wounded and was targeted because it was the most prominent building in the area.[22][21] In July, Syria entered the siege with shelling from tanks and artillery shells fired into the camp.[18] Repeated attempts by outside Palestinian factions to assist those inside the camp was met with ill fortune due to complications with the competing groups. This was particularly evident with an increase in factionalism within the Palestinian groups in the camp.[21] The raising of Palestinian and Lebanese flags in the area was a sign of provocation that led to an increased military assault in late July.[23][19]

An agreement was reached between the groups by a representative of the Arab League on August 11, 1976, the day before the massacre. The combatants were assured that they would leave the camp, along with the civilians with assistance by the Red Cross.[22] Up until this point, the Lebanese forces prevented the entry of the International Red Cross convoy to transport the wounded. With the end of the siege, 91 wounded were taken out of the camp. As people were leaving, militia groups were waiting which led to the killing of thousands.[22]

The siege of Tel al-Zaatar was the first occasion of a mass refugee killing in the Lebanese state. This furthered issues surrounding the vulnerability of the Palestinian people within Lebanon.[23] 3,000 people are reported to have died, mostly after the camp had fallen.[5]

According to Robert Fisk, many of the survivors of the massacre blamed Yasser Arafat for the high death count.[24] Arafat had encouraged those in Tel al-Zaatar to go on fighting despite the fact that they were hopelessly outnumbered and that a ceasefire was on the table, appealing to those in the camp to turn Tel al-Zaatar into "a Stalingrad"; Arafat had reportedly hoped to maximize the number of "martyrs" and thereby "capture the attention of the world."[24][25] When Arafat visited the survivors, who had been relocated to Damour after Palestinian militias had massacred the civilian population there, he was reportedly shouted down as a "traitor" and pelted with rotten vegetables.[24][26]

Aftermath

The siege enabled Bachir Gemayal to strengthen his position as the head of the Unified Military Command of the Lebanese Front militias. The siege of Tel al-Zaatar also softened the LNM’s friction with the Lebanese led army and as a result, Syria broke off its offensive on the PLO and the LNM, and agreed to an Arab League summit which temporarily suspended hostilities in Lebanon.[27]

Hafez al-Assad received strong criticism and pressure from across the Arab world for his involvement in the battle - this criticism, as well as the internal dissent it caused as an Alawite ruler in a majority Sunni country, led to a cease-fire in his war on the Palestinian militia forces.[28] The fall of camp led to commando migration to the south, particularly to the central enclave of Bint-Jubail-Aytarun and the eastern enclave of Khiam-Tayiba where tension escalated.[29]

Female political activism

Lebanon, at this time, was experiencing a period of “gender anxiety” characterized by a struggle among paternal privilege.[30] The siege of Tel al-Zaatar was a key moment that had women participating in political activism.[30] During the 1976 siege, women were heavily involved at all levels. This ranged from arranging relief events to a substantial number of women fighting alongside.[31]

Most of the people who survived the siege and its aftermath were women.[32]

Estimations of the numbers of victims

- Harris (1996: 165) states that “perhaps 3,000 Palestinians, mostly civilians, died in the siege and its aftermath”[33]

- Cobban (p. 142) writes that 1,500 camp occupants were killed in one day and a total of 2,200 were killed throughout the events.

- Canadian artist Jayce Salloum stated that 2,000 people died during the entire siege, and 4,000 were wounded.[34]

Controversy

Many PLO members and pan-arabist groups refer to as the siege as a massacre orchestrated by the Lebanese Front, while the pro-LF claim that the siege was a battle with no war crimes committed. Many put the blame of this high Palestinian death toll on Yasser Arafat for using a "Getting the most martyrs possible" policy in the siege to catch the eyes of the world in their battle.

See also

References

- ^ Price, Daniel E. (1999). Islamic Political Culture, Democracy, and Human Rights: A Comparative Study. Greenwood Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0275961879, p. 68.

- ^ Lisa Suhair Majaj, Paula W. Sunderman, and Therese Saliba Intersections Syracuse University Press ISBN 0815629516 p. 156

- ^ Samir Khalaf, Philip Shukry Khoury (1993) Recovering Beirut: Urban Design and Post-war Reconstruction, Brill, ISBN 9004099115 p. 253

- ^ Younis, Mona (2000) Liberation and Democratization: The South African and Palestinian National Movements University of Minnesota Press, ISBN 0816633002 p. 221

- ^ a b Dilip., Hiro (1993). Lebanon : fire and embers : a history of the Lebanese civil war. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 48. ISBN 0-297-82116-4. OCLC 925077506.

- ^ United States Army Human Engineering Laboratory (June 1979). Military Operations in selected Lebanese built-up areas, 1975–1978 (PDF). Technical Memorandum 11–79 (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2014.

- ^ Khoury, Elias (2012). "Rethinking The Nakba". Critical Inquiry. 38 (2): 250–266. doi:10.1086/662741. S2CID 162316338.

- ^ a b c d United States Army Human Engineering Laboratory (June 1979). Military Operations in selected Lebanese built-up areas, 1975–1978 (PDF). Technical Memorandum 11–79 (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2014.

- ^ "Kataeb Party", Wikipedia, 2021-03-09, retrieved 2021-03-11

- ^ Dilip., Hiro (1993). Lebanon : fire and embers : a history of the Lebanese civil war. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 48. ISBN 0-297-82116-4. OCLC 925077506.

- ^ Dilip., Hiro (1993). Lebanon : fire and embers : a history of the Lebanese civil war. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 42. ISBN 0-297-82116-4. OCLC 925077506.

- ^ Bradley, Douglas (1982). "Was Truth the First Casualty? American Media and the Fall of Tal Zaatar". Arab Studies Quarterly. 4: 200–210.

- ^ a b c United States Army Human Engineering Laboratory (June 1979). Military Operations in selected Lebanese built-up areas, 1975–1978 (PDF). Technical Memorandum 11–79 (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2014.

- ^ Karantina massacre#cite note-H1500-6

- ^ a b c d United States Army Human Engineering Laboratory (June 1979). Military Operations in selected Lebanese built-up areas, 1975–1978 (PDF). Technical Memorandum 11–79 (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2014.

- ^ Dilip., Hiro (1993). Lebanon : fire and embers : a history of the Lebanese civil war. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 41. ISBN 0-297-82116-4. OCLC 925077506.

- ^ a b c d e United States Army Human Engineering Laboratory (June 1979). Military Operations in selected Lebanese built-up areas, 1975–1978 (PDF). Technical Memorandum 11–79 (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2014.

- ^ a b أبو عبود, إيلي (2018). "تل الزعتر - خفايا المعركة". Al Jazeera Documentary.

- ^ a b Iraqi, Yousuf (2018). "تل الزعتر - خفايا المعركة". Al Jazeera Documentary.

- ^ Dilip., Hiro (1993). Lebanon : fire and embers : a history of the Lebanese civil war. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 34. ISBN 0-297-82116-4. OCLC 925077506.

- ^ a b c Iraki, Youssif (2016). A diary of a doctor in Tal Al-Zaatar, a Palestinian refugee camp, in Lebanon. [Pierrefonds, Québec]: [Ihmayed Ali]. ISBN 978-0-9958059-0-3. OCLC 1032943743.

- ^ a b c اللبدي, د. عبد العزيز (2016). "حكايتي مع تل الزعتر". منشورات ضفاف.

- ^ a b Khawaja, Bassam (2011). War and Memory: The Role of Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon. Macalester College. History Department. pp. 1–168.

- ^ a b c Fisk, Robert (2002). Pity the Nation: The Abduction of Lebanon. New York: Thunder's Mouth/Nation Books. p. 107.

- ^ Randal, Jonathon (2012). Tragedy of Lebanon: Christian Warlords, Israeli Adventurers, and American Bunglers. Just World Books; Reprint edition. p. 171. ISBN 978-1935982166.

- ^ Karsh, Efraim (2014). "No Love Lost". The Myth of Palestinian Centrality: 27–29.

- ^ Dilip., Hiro (1993). Lebanon : fire and embers : a history of the Lebanese civil war. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 42. ISBN 0-297-82116-4. OCLC 925077506.

- ^ Bradley, Douglas (1982). "Was Truth the First Casualty? American Media and the Fall of Tal Zaatar". Arab Studies Quarterly. 4: 200–210.

- ^ Dilip., Hiro (1993). Lebanon : fire and embers : a history of the Lebanese civil war. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 48. ISBN 0-297-82116-4. OCLC 925077506.

- ^ a b Khazaal, Natalie (2018). Pretty Liar: Television, Language, And Gender In Wartime Lebanon. New York: Syracuse University Press. p. 215.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Nader, Laura (August 1993). "Gender in Crisis: Women and the Palestinian Resistance Movement. Julie M. Peteet". American Ethnologist. 20 (3): 640–641. doi:10.1525/ae.1993.20.3.02a00250.

- ^ اللبدي, د. عبد العزيز (2016). "حكايتي مع تل الزعتر". منشورات ضفاف.

- ^ Faces of Lebanon: sects, wars, and global extensions. 1997-07-01.

- ^ "111101 - Facts - Chronology - Lebanese war - 1976". Archived from the original on 2008-03-20. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

Bibliography

- William Harris, Faces of Lebanon. Sects, Wars, and Global Extensions (Markus Wiener Publishers, Princeton, New Jersey, 1996) [ISBN missing]

- Helena Cobban, The Making of Modern Lebanon (Hutchinson, London, 1985, ISBN 0091607914)

- George W. Ball, Error and betrayal in Lebanon (Foundation for Middle East Peace, Washington, D.C., 1984, ISBN 0-9613707-1-8)

External links

- Information and Pictures from the Lebanese Civil War 'liberty05.com' Tel-el-Zaatar (the Hill of Thyme) was the largest and strongest Palestinian refugee camp established in 1948, Includes several pictures from The Battle of Tel al-Zaatar.

- Arafat's Massacre of Damour - Canada Free Press [1]

- Google Earth view of Tel al Zaatar

- Conflicts in 1976

- Battles of the Lebanese Civil War

- Massacres of the Lebanese Civil War

- History of Palestine (region)

- Palestinian refugees

- 1976 in Lebanon

- Massacres of Palestinians

- Beirut in the Lebanese Civil War

- Persecution of Muslims by Christians

- Mass murder in 1976

- Violations of medical neutrality during the Arab–Israeli conflict

- 20th-century sieges