Torato Umanuto

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2012) |

Torato Umanuto (Hebrew: תּוֹרָתוֹ אֻמָּנוּתוֹ [toʁaˈto ʔumanuˈto], transl. 'Torah study is his job') is a special government arrangement in Israel that allows young Haredi Jewish men who are enrolled in yeshivas to complete their studies before they are conscripted into the Israeli military. Historically, it has been mandatory in Israeli law for male and female Jews, male Druze, and male Circassians to serve in the military once they become 18 years of age, with male conscripts required to serve for three years and female Jewish conscripts required to serve for two years.

Haredi Jews maintain that the practice of studying the Torah (or reciting), when undertaken by great Torah scholars or their disciples, is crucial in defending the Israeli people from threats, similar to an additional "praying division" of the military. In practice, the Torato Umanuto arrangement provides a legal route whereby Haredi rabbis and their disciples can either enroll for a shortened service period of four months or otherwise be exempted from compulsory military service altogether.

The source of the phrase Torato Umanuto is taken from the Talmud:

"For it was taught: If companions [scholars] are engaged in studying, they must break off for the reading of the shema, but not for prayer. R. Johanan said: This was taught only of such as R. Simeon b. Yohai and his companions, whose Torah study was their occupation."

Establishment of the agreement[edit]

During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, erstwhile Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion reached a special arrangement with Israel's Haredi Jews (then represented by Agudat Yisrael and Yitzhak-Meir Levin) in which a small part of the community's senior yeshiva disciples (400 men) would be temporarily exempted from serving in the Israel Defense Forces, but only as long as their sole occupation was studying the Torah, which a number of Haredi Jews devote and occupy themselves with for the majority of their day as a religious commandment. The arrangement's original purpose was to reach a comprehensive accommodation, later called the secular–religious status quo, between the secular community and the Haredi population who were then living under the British Mandate for Palestine, and by extension preventing an internal conflict within the Palestinian Jewish community (the Yishuv) amidst high tensions with the region's Arabs.[1]

By contrast, Israelis who belong to the Religious Zionist community are conscripted, often under the yeshiva system of the Hesder program, which combines Torah study with military service.

Over the years, as the Israeli population grew, the number of Haredi men eligible for exemption under the Torato Umanuto grew significantly; from 800 men in 1968 to 41,450 in 2005, compared to seven million for the entire population of Israel. In percentage terms, 2.4% of the soldiers enlisting to the army in 1974 were benefiting from Torato Umanuto compared to 9.2% in 1999, when it was projected that the number would reach 15% by the year 2012. The issue turned into a political debate within Israeli society as to who should be obliged to risk his or her life serving in the Israel Defense Forces; many non-Haredi Israeli Jews, including those in the Religious Zionist sector, began to complain over the uneven burden of military service. Beyond the three years of regular-compulsory service for men and two for women, men also serve as military reserve force, including military exercises on a regular basis until they turn 50.

For many years the Torato Umanuto arrangement had the status of a regulation under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Defense (Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion also had the Defense portfolio). In the 1990s the High Court of Justice of Israel ruled that the Defense minister had no authority to determine the extent of these exemptions. The Supreme Court postponed the application of the ruling to give the government time to resolve the matter.

Judicial repeal of exemption[edit]

The court ruled in 2017 that blanket military service exemptions for Haredi yeshiva students were illegal and discriminatory.[2] As of 2024, the government had not complied with the fully extent of the court's ruling.

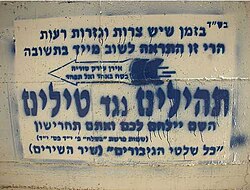

In March 2024, Attorney General Gali Baharav-Miara instructed both the Education Ministry and the Defense Ministry to begin the drafting process for Haredi men.[2] On the night of 1 April, the coalition government stated that it had not agreed to an extension of the exemption, which had thus expired.[1] Following a number of delays, a letter from Prime Minister Netanyahu requesting a one-month extension, and the passing of the deadline, on 1 April 2024, the Supreme Court decided that the Haredim would no longer receive an exemption from military service and that yeshivas could no longer receive the associated government subsidies.[3][4][5] The Times of Israel reported that per government figures, 1,257 yeshivas would lose subsidies for 49,485 students receiving the exemption.[4] Haredi lawmakers, members of the political parties United Torah Judaism and Shas, and supporters of the coalition government have stated their intention to walk out if the exemption removal is enforced; Anshel Pfeffer, a journalist for the newspaper Haaretz, argued that these threats were hollow. Haredi youth in the ultra-Orthodox neighbourhood of Mea Shearim in Jerusalem burned Israeli flags and military uniforms in protest.[3][6] The opposition politician Benny Gantz spoke out in support of the court decision.

Following the 1 April lapse, the Supreme Court stated that it would convene on 2 June 2024 to hear a case regarding the conscription of Haredi men.[2] The case will be proceeded over by an expanded, nine-judge panel, as opposed to the standard three-judge panel.

Tal Law[edit]

In accordance with the judicial ruling, Prime Minister Ehud Barak set up the Tal committee in 1999. The Tal committee reported in April 2000, and its recommendations were approved by the Knesset (Israeli parliament) in July 2002; the new Tal Law, as it came to be known, was passed with 51 votes in favour and 41 against. The new law provided for a continuation of the Torato Umanuto arrangement under specific conditions laid down in the law; it was hoped that the number of exemptions would gradually reduce. The new law did not however put an end to controversies and disagreements.

In 2005, then Justice Minister Tzipi Livni stated that the Tal Law, which by then had yet to be fully implemented, did not provide an adequate solution of the problem of Haredi conscription as only 1,115 of the 41,450 yeshiva students covered by the arrangement had taken the "decision year" provided by the law, and of these only 31 had later enlisted in the Israel Defense Forces.[7] In 2007 the Tal Law was extended until August 2012. In January 2012, Defense Minister Ehud Barak said his ministry was preparing an alternative to the Tal Law. Dozens of IDF reserve soldiers had put up what they called "the suckers' camp" near the Tel Aviv Savidor Central Railway Station, to protest the possible extension of the Tal Law. Several politicians, public figures, disabled IDF veterans and high school and university students visited the protest encampment.[8]

In February 2012 the High Court of Justice (a role of the Supreme Court of Israel) ruled that the Tal Law in its current form was unconstitutional and could not be extended beyond August.[9] Prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu said that the government would formulate a new bill that would guarantee a more equal sharing of the burden by all parts of Israeli society.[10] The issue was also part of a possible government collapse leading into the 2012-2013 election.

See also[edit]

- Hardal

- Haredim and Zionism

- Hesder - a Religious Zionist ("National Religious") yeshiva framework developed by Rav Yehuda Amital, combining Torah study and military service

- Nahal Haredi - the IDF's Netzah Yehuda Battalion, which facilitates Haredi service in combat roles

- Religion in Israel

- Status quo (Israel)

References[edit]

- ^ a b Kingsley, Patrick; Reiss, Johnathan (30 March 2024). "Dispute Over Conscription for Ultra-Orthodox Jews Presents New Threat to Netanyahu". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ a b c "Israeli Supreme Court to review Haredi conscription case in June". i24 News. 10 April 2024. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ a b Tondo, Lorenzo; Kierszenbaum, Quique; Mamo, Alessio (2024-04-04). "'I will never join the army': ultra-Orthodox Jews vow to defy Israeli court orders". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-04-12.

- ^ a b "U.S. Haredi leadership find consensus in lamenting Israel's yeshiva draft changes • Shtetl - Haredi Free Press". www.shtetl.org. Retrieved 2024-04-12.

- ^ Peretz, Sami (2024-04-10). "Israel must stop financing the ultra-Orthodox draft-dodgers". Haaretz. Retrieved 2024-04-12.

- ^ "Haredi youth in Mea Shearim set fire to Israeli flag during Brothers in Arms protest". The Times of Israel. 31 March 2024. Retrieved 12 April 2024.

- ^ Yuval Yoaz (2005-09-27). "Justice Minister: Implementation of Tal Law 'unsatisfactory'". Haaretz. Retrieved 2012-01-27.

- ^ Gili Cohen and Jonathan Lis (2012-01-27). "Netanyahu: Knesset, not cabinet, will decide fate of Tal Law". Haaretz. Retrieved 2012-01-27.

- ^ Yair Ettinger (2012-02-27). "Israeli Haredi parties on possible end to Tal Law: We will give our lives to the Torah". Haaretz. Retrieved 2012-03-19.

- ^ Yair Ettinger and Gili Cohen (2012-02-21). "Israel's High Court rules Tal Law unconstitutional, says Knesset cannot extend it in present form". Haaretz. Retrieved 2012-03-19.