Victor Maurel

Victor Maurel (17 June 1848 – 22 October 1923) was a French baritone who enjoyed an international reputation in opera. He sang in opera houses in Paris and London, Milan, Moscow, New York, St Petersburg and many other venues. He was particularly associated with the operas of Verdi and created leading characters in the premieres of the composer's final operas, as Iago in Otello (1887) and in the title role of Falstaff (1893). He was also known for his portrayal of Mozart's Don Giovanni, and won Wagner's praise for his performances in Lohengrin, Tannhäuser and Der fliegende Holländer. After retiring from the stage he taught singing in Paris, London and New York.

Biography[edit]

Maurel was born in Marseille on 17 June 1848.[1] He studied at the Paris Conservatoire under Daniel Auber, with Charles-François Duvernoy and Eugène Vauthrot as his main teachers. Among his fellow students were Victor Capoul and Pierre Gailhard, and according to Le Figaro the three made the Conservatoire "resound with a picaresque tumult of adventures, jokes and vocal triumphs with which all the chronicles of Paris vibrated for thirty years".[2] In addition to his escapades, Maurel won first prizes for singing and opera.[3]

He made his début in Marseille (1867) in Guillaume Tell, and the following year appeared at the Paris Opéra as de Nevers in Les Huguenots, the Count di Luna in Il trovatore and roles in L’Africaine and La favorite. At the Opéra Jean-Baptiste Faure was established as the leading baritone, and Maurel decided to pursue his career abroad.[4] He left the Opéra in 1869 and appeared in opera houses in Cairo, London, Milan, Moscow, New York and St Petersburg. In New York he sang Amonasro in the first American production of Aida (1873).[1][4]

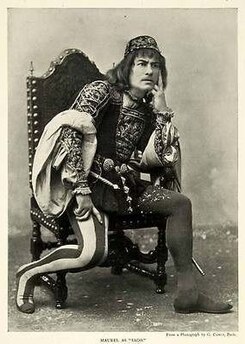

In 1879 Maurel returned to the Paris Opéra and sang there frequently until 1894, in between foreign tours and a financially unsuccessful spell as co-director of the revived Théâtre-Italien at the Théâtre des Nations.[4] At La Scala, Milan in 1881 he sang the title role in the premiere of Verdi's revised version of Simon Boccanegra. Verdi was sufficiently impressed to cast him as Iago in the premiere of Otello (1887)[1] and – after protracted haggling about fees[5] – in the title role for the first performance of Falstaff (1893), both at La Scala. The Milan company took Falstaff on a European tour, but with the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War still an affront to French national pride, Maurel refused go with the company to Berlin.[6] Between the two Verdi premieres Maurel created the role of Tonio in Leoncavallo's Pagliacci at the Teatro Dal Verme, Milan (1892).[1] At his insistence Leoncavallo changed the title of the piece from the singular to the plural so that the tenor was not the only pagliacco (clown) of interest.[7]

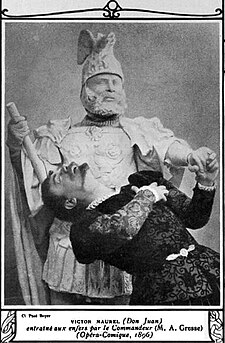

Maurel's antipathy to Germany did not extent to its music. He was much impressed by Wagner's operas,[2] and he appeared as Telramund in Lohengrin, Wolfram in Tannhäuser and in the title role of Der fliegende Holländer.[1] On a visit to London, Wagner sought Maurel out to congratulate him on his Covent Garden performances in the roles.[3] According to Le Figaro, Maurel's chief musical gods nevertheless remained Mozart and Verdi.[2] One of the roles with which Maurel was particularly associated was Don Giovanni. When he played the part at the Opéra-Comique he was described as "a personal, tormented, romantic, complicated Don Giovanni",[2] and when he played it at Covent Garden Bernard Shaw wrote that he was immeasurably better than any other exponent of the part in recent years, although Shaw thought him more suited to melodramatic parts in Verdi operas.[8]

According to Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Maurel was outstanding not so much for the timbre or resonance of his voice as for his perfect breath control and skill as an actor.[1] Le Figaro compared him to "le grand Irving" (Sir Henry Irving) and he acted on the non-musical stage in the early 1900s.[2] The Manchester Guardian said that he was among baritones what Chaliapin was to basses, "combining the genius of the actor as well as the singer".[9]

Maurel returned to the Metropolitan Opera in 1894–1896 and 1898–99 and after retiring from performing he designed its production of Gounod’s Mireille (1919). For a time he had an opera studio in London, and from 1909 until his death he taught in New York. He wrote books on singing and opera staging, including Le Giant remove par la science (1892), Un Probleme d'art (1893), L'Art du chant (1897), and memoirs, Dix ans de carriere (1897).[1]

Some examples of his singing are preserved on gramophone records he made in the early 20th century. These recordings, which include a few French songs and arias from Otello, Falstaff and Don Giovanni, have been reissued on CD by various companies. In a study of old recordings J. B. Steane comments that some of Maurel's are of cheap music unworthy of the singer's attention and others fail to show why he was so highly regarded in his prime, but that Don Giovanni's Serenade shows "a well-preserved, virile voice and an aristocratic finish to the style" and Maurel's performance of Falstaff's short aria "Quand' ero paggio" "impresses for its buoyancy – 'ero sottile, sottile, sottile' bounces gaily on its podgy toes – and the colourful vocal acting. It is a delightful memento".[10]

Maurel was married to Frédérique Rosine de Grésac, a well-known writer who used the pen-name Fred de Gresac.[11] In about 1909 they moved to New York, where Maurel died on 22 October 1923 at the age of 75.[1]

Gallery[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rosenthal, Harold, and Karen Henson. "Maurel, Victor", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2009 (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e "Montaudran", "Victor Maurel", Le Figaro, 24 October 1923, p. 1

- ^ a b "Mr Victor Maurel", The Daily Telegraph, 24 October 1923, p. 6

- ^ a b c Martin, p. 253

- ^ Phillips-Matz, p. 712

- ^ "Verdi's Falstaff at Berlin", The Times, 2 June 1893, p. 5

- ^ Dryden, p. 37

- ^ Shaw, p. 338

- ^ "Victor Maurel", The Manchester Guardian, 25 October 1923, p. 8

- ^ Steane, p. 19

- ^ Bordman, Gerald, and Thomas S. Hischak. "Gresac, Fred(erique Rosine) De", The Oxford Companion to American Theatre, Oxford University Press 2004 (subscription required)

Sources[edit]

- Dryden, Konrad (2007). Leoncavallo: Life and Works. Plymouth: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5880-0.

- Martin, Jules (1895). Nos artistes: portraits et biographies (in French). Paris: Ollendorff. OCLC 1157118470.

- Phillips-Matz, Mary Jane (1993). Verdi: A Biography. London and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-313204-7.

- Shaw, Bernard (1898). Dan H Laurence (ed.). Shaw's Music – The Complete Music Criticism of Bernard Shaw, Volume 2. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-0-37-031271-2.

- Steane, J. B (1993) [1974]. The Grand Tradition: Seventy Years of Singing on Record (second ed.). London: Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-71-560661-2.