Battle of Nineveh (627)

| Battle of Nineveh | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 | |||||||

Anachronistic depiction of the Battle of Nineveh in a late 15th century illuminated French manuscript (by Robinet Testard) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Heraclius |

Rahzadh † Vahram-Arshusha V (POW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

25,000-50,000 Byzantines[1] 40,000 Göktürks (deserted) | 12,000[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | 6,000[2] | ||||||

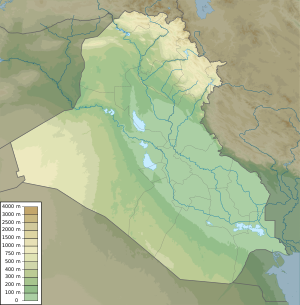

Location within West and Central Asia | |||||||

The Battle of Nineveh (Greek: Ἡ μάχη τῆς Νινευί) was the climactic battle of the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628.

In mid-September 627, Heraclius invaded Sasanian Mesopotamia in a surprising, risky winter campaign. Khosrow II appointed Rhahzadh as the commander of an army to confront him. Heraclius' Göktürk allies quickly deserted, while Rhahzadh's reinforcements did not arrive in time. In the ensuing battle, Rhahzadh was slain and the remaining Sasanians retreated.

The Byzantine victory later resulted in civil war in Persia, and for a period of time restored the (Eastern) Roman Empire to its ancient boundaries in the Middle East. The Sasanian civil war significantly weakened the Sasanian Empire, contributing to the Muslim conquest of Persia.

Prelude[edit]

When Emperor Maurice was murdered by the usurper Phocas, Khosrow II declared war under the pretext of avenging his benefactor's death. While the Persians were successful over the course of earlier stages in the war, conquering much of the Levant, Egypt, and even some of Anatolia, the resurgence of Heraclius eventually led to the Persians' downfall. Heraclius' campaigns tilted the balance towards the Romans, forcing the Persians on the defensive. Allied with the Avars, the Persians attempted to take Constantinople, but were defeated.[3]

While the Siege of Constantinople was taking place, Heraclius allied with what Byzantine sources called the Khazars under Ziebel, who are identified with the Western Turkic Khaganate of the Göktürks led by Tong Yabghu,[4] plying him with wondrous gifts and a promise of the reward of the porphyrogenita Eudoxia Epiphania. The Caucasus-based Turks responded by sending 40,000 of their men to invade the Caucasus in 626, inciting the Third Perso-Turkic War.[5] Joint Byzantine and Göktürk operations were focused on besieging Tiflis.[6]

Invasion of Mesopotamia[edit]

In mid-September 627, leaving Ziebel to continue the Siege of Tbilisi, Heraclius invaded the Persian Empire, this time with between 25,000 and 50,000 troops and 40,000 Göktürks. The Göktürks, however, quickly deserted him because of the strange winter conditions.[1] Heraclius was tailed by Rhahzadh's army of 12,000,[2] but managed to evade Rhahzadh and entered Mesopotamia (modern Iraq).[1] Heraclius acquired food and fodder from the countryside, so Rhahzadh, following through countryside already stripped, could not easily find provisions for his soldiers and animals.[7][8]

On December 1, Heraclius crossed the Great Zab River and camped near the ruins of the capital of the former Assyrian Empire of Nineveh in Persian ruled Assyria/Assuristan. This was a movement from south to north, contrary to the expectation of a southward advance. However, this can be seen as a way to avoid being trapped by the Persian army in case of a defeat. Rhahzadh approached Nineveh from a different position. News that 3,000 Persian reinforcements were approaching reached Heraclius, forcing him to counteract.[8] He gave the appearance of retreating from Persia by crossing the Tigris.[9]

Field of battle[edit]

Heraclius had found a plain west of the Great Zab some distance from the ruins of Nineveh.[10] This allowed the Byzantines to take advantage of their strengths in lances and hand-to-hand combat. Furthermore, fog reduced the Persian advantage in missile-shooting soldiers and allowed the Byzantines to charge without great losses from missile barrages.[9] Walter Kaegi believes that this battle took place near Karamlays Creek.[11]

Battle[edit]

On December 12, Rhahzadh deployed his forces into three masses and attacked.[12] Heraclius feigned retreat to lead the Persians to the plains before reversing his troops to the surprise of the Persians.[9] After eight hours of fighting, the Persians suddenly retreated to nearby foothills, but it was not a rout.[13][14] 6,000 Persians fell.[2][15]

Nikephoros' Brief History tells that Rhahzadh challenged Heraclius to single combat. Heraclius accepted and killed Rhahzadh in a single thrust; two other challengers fought and also lost.[2][13] The account of another Byzantine historian, Theophanes the Confessor, supports this.[16] However, doubt has been cast on whether or not this actually occurred.[17] In any case, Rhahzadh died at some point during the battle.[2]

The 3,000 Persian reinforcements arrived too late for the battle.[2][18]

Aftermath[edit]

The victory at Nineveh was not total as the Byzantines were unable to capture the Persian camp.[19] However, the victory was effective in preventing further Persian resistance.[19]

With no Persian army left to oppose him, Heraclius' victorious army plundered Dastagird, Khosrow's palace, and gained tremendous riches while recovering 300 captured Byzantine/Roman standards accumulated over years of warfare.[20] Khosrow had already fled to the mountains of Susiana to try to rally support for the defense of Ctesiphon.[13][21] Heraclius could not attack Ctesiphon itself because the Nahrawan Canal was blocked by the collapse of a bridge.[20]

The Persian army rebelled and overthrew Khosrow II, raising his son Kavad II, also known as Siroes, in his stead. Khosrow perished in a dungeon after suffering for five days on bare sustenance—he was shot to death slowly with arrows on the fifth day.[22] Kavad immediately sent peace offers to Heraclius. Heraclius did not impose harsh terms, knowing that his own empire was also near exhaustion. Under the peace treaty, the Byzantines regained all their lost territories, their captured soldiers, a war indemnity, and of great spiritual significance, the True Cross and other relics that were lost in Jerusalem in 614.[22][23] The battle was the last conflict of the Roman–Persian Wars.

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c Kaegi 2003, pp. 158–159

- ^ a b c d e f g Kaegi 2003, p. 167

- ^ Norwich 1997.

- ^ Kaegi 2003, p. 143

- ^ Norwich 1997, p. 92

- ^ Kaegi 2003, p. 144

- ^ Kaegi 2003, pp. 159

- ^ a b Kaegi 2003, pp. 160

- ^ a b c Kaegi 2003, pp. 161

- ^ Kaegi 2003, pp. 162

- ^ Kaegi 2003, pp. 163

- ^ Kaegi 2003, pp. 161–162

- ^ a b c Norwich 1997, p. 93

- ^ Kaegi 2003, p. 163

- ^ Kaegi 2003, p. 169

- ^ Konieczny, Peter (June 5, 2016). "Single Combat? The Duel between Heraclius and Razhadh at the Battle of Nineveh". Karwansaray Publishers. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ Crawford, Peter (2013). The War of the Three Gods: Romans, Persians and the Rise of Islam. South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Books Ltd. p. 71. ISBN 978-1848846128.

- ^ Kaegi 2003, p. 170

- ^ a b Kaegi 2003, p. 168

- ^ a b Kaegi 2003, p. 173

- ^ Oman 1893, p. 211

- ^ a b Norwich 1997, p. 94

- ^ Oman 1893, p. 212

References[edit]

- Kaegi, Walter Emil (2003). Heraclius: emperor of Byzantium. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521814591.

- Norwich, John Julius (1997). A Short History of Byzantium. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0679772699.

- Oman, Charles (1893). Europe, 476–918. Macmillan.